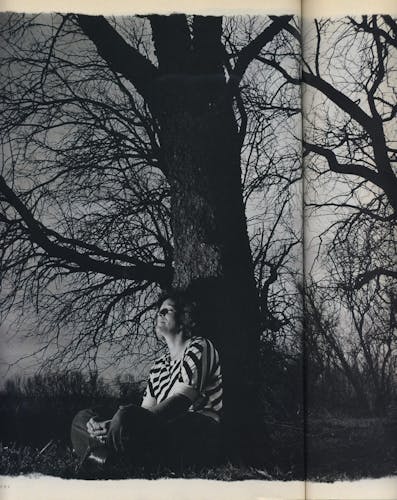

A couple of miles north of Childress, near a curving dirt road that intersects two cotton fields, there stands a drooping, wide-limbed horse apple tree with its largest branch broken nearly in half. It is the hanging tree, one of the most talked-about landmarks in town. Yet most residents know of it only by hearsay. “They’d prefer not to go out there, if you know what I mean,” says David McCoy, the district attorney. “Not that they’ll tell you the place is haunted. But there’s just, well, something about it …” and his voice trails off.

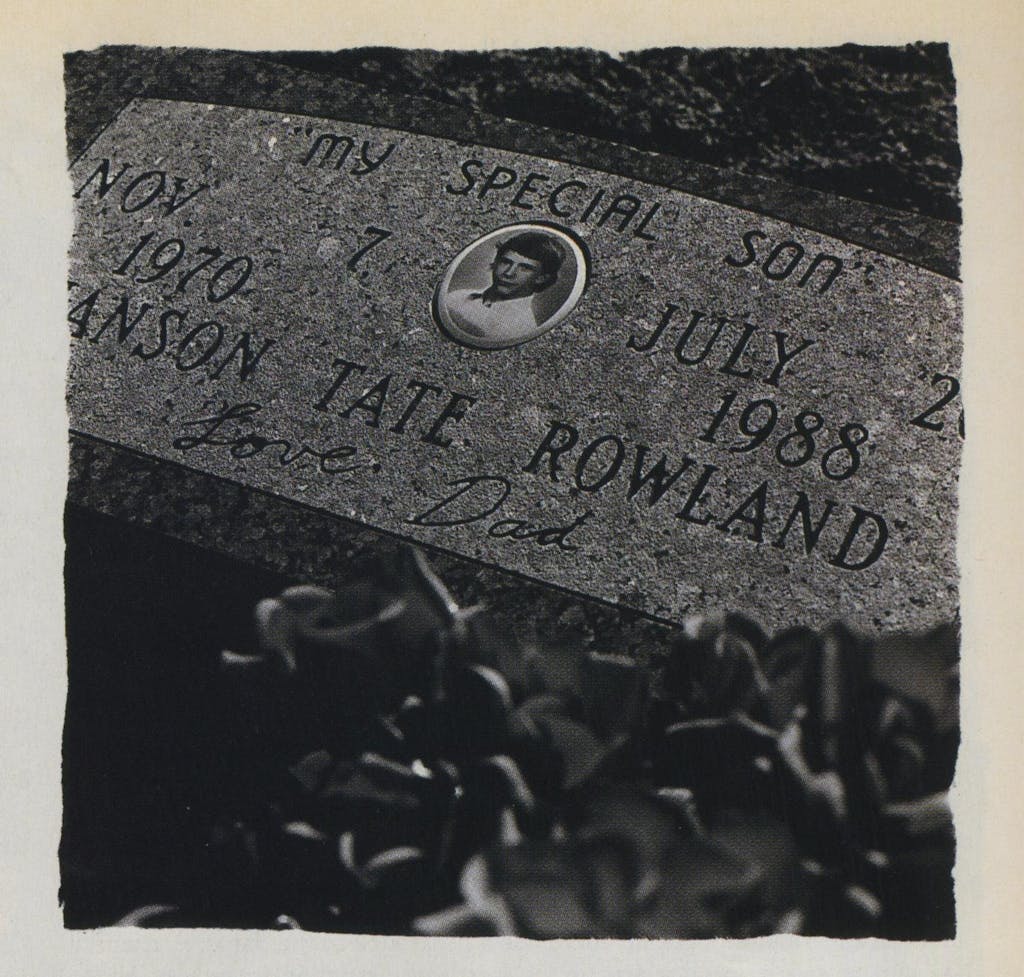

On a summer evening in 1988, a local teenager, Tate Rowland, was found hanging from the tree, his body slowly twisting counterclockwise. Though the county sheriff who investigated his death would later say that every family member he interviewed couldn’t imagine Tate wanting to take his own life, an eyewitness said he saw Tate hang himself, and the case was officially classified as suicide. The episode was regarded as one of those tragic, puzzling mysteries—the act of impulsive youth—until May 1991, when Tate’s elder sister was found dead, face down on a bed. And then, in quiet little Childress, a town of 5,800 in the southeast corner of the Panhandle, the panic hit like a clap of thunder.

Terrifying stories that had been quietly passed around Childress since Tate’s death began to emerge in public. Tate, it was said, had been murdered by a satanic cult—devil worshipers living right in the middle of town. According to the grapevine, ten, maybe twelve cult members—the editor of the Childress Index had heard it might be twenty—were at the hanging tree that night to sacrifice Tate; his sister, 27-year-old Terrie Trosper, was then killed because she had learned too much about the cult. Fear and suspicion spread faster than a prairie fire. Stone altars, mutilated animals, defaced tombstones, and black-robed cult members meeting in abandoned houses were sighted. More than one person reported seeing a young Childress man eat pages from a Bible and then foam at the mouth. Another rumor had the cult searching for a blond child to use as a human sacrifice.

Every town has at least one spooky ghost story, but the events in Childress seemed too peculiar to dismiss as fiction. There were too many unanswered questions about the deaths of Tate and Terrie, too many coincidences, too many bizarre satanic-related confessions from people who said they knew about the crimes. The sheriff reopened the old cases, and the district attorney convened a grand jury to investigate them. Bodies were exhumed from the Childress Cemetery. An expert on satanic cults arrived to give a seminar to the townspeople on how to spot a devil worshiper and later helped the sheriff sift through evidence. Certain citizens were subpoenaed to tell the grand jury what they knew about the cult and the murders; others freely called up the sheriff’s office and provided names and phone numbers of people they believed were cult members.

For those in town who had heard about the growing international satanic conspiracy—composed of secret local cults all bent on a mission of subversion—the news about Tate and Terrie served only to confirm their suspicions that the devil had come to Childress. Satan hunters had long insisted that deadly occult organizations were moving into the heartland of America, luring in new youthful recruits with sex and drugs, the lyrics of heavy metal music, and fantasy games like Dungeons and Dragons. The threat, they said, could not be taken lightly. Indeed, most law enforcement agencies in the country were placing on their staffs a specialized “cult cop,” an officer trained to spot satanic villainy. The Texas Department of Public Safety was sending local police departments a handout listing thirty ways to determine if someone had been killed as a result of an occult ritual. Cult awareness agencies were springing up to remind the public that today’s candle-burning teenager might be tomorrow’s baby killer. Small towns, the experts said, were particularly susceptible to cults, which look for remote areas where their activities can be more easily concealed.

It was no surprise, then, that the Satan scare nearly overwhelmed little Childress. The investigation into the deaths of Tate Rowland and Terrie Trosper became the focus of the entire community. For a few townspeople, however, the cult stories posed a different threat entirely. To them, the threat was the power of gossip. They saw rational thinking overcome by fright and apprehension and, yes, by the pure pleasure that comes from swapping thirdhand information over a cup of coffee. When these people looked back on the events that had unfolded during the past year in Childress, they didn’t see the devil exposed. What they saw was a modern-day witch-hunt.

RABBLE-ROUSING

In 1988 Tate Rowland was seventeen years old, a popular, good-looking kid with a wild streak. Down at the sheriff’s office, he had a reputation as a hot-rodder and a drinker. In his blue Ford shortbed pickup truck with its high-dollar custom stereo system, installed over in Wichita Falls, Tate would roar up and down the Childress drag, a mile-long, stoplight-dotted stretch of U.S. 287 that cuts past such teen hangouts as the My-T-Burger fast-food restaurant, the 24-hour car wash, and the United Supermarket parking lot. Sometimes he would drive thirty miles south to Paducah to flirt with teenage girls whose daddies had oil money. “In Childress,” says Bobby Reynolds, one of Tate’s best friends, “there isn’t a whole lot for a teenager to do except ride around, chase girls, drink beer, get in a little trouble.”

Actually, Childress, a former railroad town, doesn’t have the typically torpid look of other small West Texas communities. It has a thriving hospital. A new state prison built at the edge of town has provided more than three hundred jobs. Though Childress’ reputation suffered a setback early last year when its rotund sheriff, Claude Lane, was caught selling marijuana, most residents prefer to focus on the town’s all-American qualities, such as the local girl who was recently named first runner-up in the national Miss Teenage America pageant and the state district judge who dresses up as Santa Claus every Christmas and passes out handmade toys.

Childress remains just small enough that the movie house downtown would need to open only a couple of nights a week to accommodate everyone who wants to see the feature film. It’s also small enough that it is hard to do anything that somebody else—either by accident or from simple curiosity—doesn’t happen to hear about. On its flat, featureless landscape, people who love and hate each other come face to face almost every day.

As a result, just about everyone knew Tate Rowland. Half the town liked him; half the town thought he could use a good kick in the pants. A friendly boy with an easy grin, Tate was, in the words of district attorney McCoy, “a rabble-rouser.” When he would get a little beer-drunk, he liked to scuffle, especially if he thought someone was trying to put a move on his sometime girlfriend, a cute, pixie-size blond named Karen Hackler. Once Tate went after his buddy Bobby Reynolds because he saw Bobby and Karen in the same car. With one punch, Bobby broke Tate’s jaw. “I don’t think Tate ever won a fight,” McCoy told me, “but he would fight a buzz saw.”

Tate’s relationship with Karen, the daughter of a prominent farmer, was one of those dramatic love-hate affairs that young people seem able to navigate so well. “Tate and Karen were always in their cars, chasing each other up and down the drag, mad or jealous at each other about something,” says Ty Copeland, another of Tate’s friends. The Hackler family regularly complained to the police that Karen had tried to break up with Tate but that he kept harassing her—that he stole her pocketbook and jewelry, that he had driven up to the front of her home and then squealed away, his tires slinging gravel against the house. Once, when Kevin Hackler told Tate to stay away from his sister, either Tate tried to run over Kevin with a pickup truck or Kevin hit the side of the truck with an ax handle. The grand jury, not sure which story to believe, did not indict either boy.

Frankly, a small town’s criminal justice system develops a capacity for patience with its youth; otherwise, its court dockets would be full of criminal mischief cases. In January 1988, the police did arrest Tate for assault after Karen charged that he had jumped over the counter at Allsup’s Convenience Store, where she worked nights, and attempted to choke her. But when the case went before the grand jury, no indictment was issued. During the lunch break, according to McCoy, the jurors saw Karen and Tate hugging in the courthouse hallway and decided to let bygones be bygones.

Nevertheless, tensions between Tate and the Hacklers reached the boiling point. Soon after the Allsup’s episode, Tate went to live with a relative in Louisiana. His father, Jimmie Rowland, a heavy-equipment operator for the railroad, had long been telling his son to stay away from the Hacklers and from Karen, who was five years older than Tate. “He didn’t think they were good for Tate,” says Tate’s stepmother, Brenda. (Jimmie would not be interviewed.) The Hacklers, in turn, claimed that Jimmie himself had threatened them. The whole thing was turning, some thought, into a Hatfield-McCoy feud.

Then, in the spring of 1988, while Tate was still out of town, Karen married another young man in Childress. Tate, according to his friends, was stunned. When he returned to town that summer, he would call or run into Karen. Tate’s friends and family said he briefly tried to get the relationship going again; Karen said he contacted her mostly to talk about his problems. Though many of Tate’s buddies would later say that he quickly returned to his old personable self, one friend admitted that Tate “showed some depression over Karen when he would have a beer or two.” Says Clifton Hodges, who had grown up with Tate: “Tate once told me that he’d like to have a country and western song played at his funeral—‘He Stopped Loving Her Today.’ ”

If Tate was upset on July 26, 1988, he didn’t show it. More than an hour before his death, around five in the afternoon, he had been seen at the United Supermarket parking lot. He made plans with some girls to drop by the city park that evening to act as their coach for a women’s league softball game. He told Bobby Reynolds that he would meet him later to split a twelve-pack of beer. Then he and a younger friend, Chad Johnston, got in a car and drove away.

It was Chad who, at six o’clock, came through the front door of Jimmie and Brenda’s home to tell them that Tate had hanged himself. Brenda later recalled that Chad “was as calm as he could be, no tear in his eye, no nothing.” The three of them rushed to the site. There, according to a chillingly concise account of the events in the Index, “Tate’s father, Jimmie Rowland, cut his son from the tree.”

Chad, then fifteen, was a quiet, unpopular kid. He was new to town; those acquainted with him said he liked hanging around the more popular Tate because Tate could always provide some excitement. Chad initially told the sheriff that he and Tate had driven to a small grove of trees where they liked to listen to music. According to his first version of the events, Tate drank a few beers, strung a rope over the limb of the horse apple tree, and announced that he was going to hang himself. He told Chad where he wanted to have his funeral. Chad thought he was kidding. Chad told the sheriff that he walked behind the car to throw a beer can into the bushes and to see if anyone was watching. When he came back three minutes later, Tate was dead.

That story presented a problem. Two rope burns were visible on Tate Rowland’s neck—one above the Adam’s apple, one below. When someone is hanged, the body weight invariably pulls the chin toward the rope so that the rope mark is always above the Adam’s apple. Could Tate have been strangled first with the rope, then hung up in the tree to make it look like suicide? Two days later, Chad was interviewed again. This time, he said Tate had tried to hang himself twice. The first time, the rope broke. According to Chad’s statement, Tate said, “I can’t even kill myself.” They went back to Tate’s house (a five-minute drive away) to get another rope, then came back to the tree. Tate, standing on the hood of the car, tied one end around the limb, the other end around his neck, and stepped off of the car.

Chad would later say that he had told different stories because he was afraid he would get in trouble for not trying to stop Tate. He insisted that Tate had talked about suicide, that Tate had been upset over Karen. At the time, the sheriff’s department decided there was nothing else it could do. The death was ruled a suicide. The county judge, standing in for the justice of the peace, saw no reason to order an autopsy, and Tate’s body was prepared for burial.

A Whisper Campaign

The rumors began at the funeral. A woman dressed in black, a veil covering her face, mysteriously slipped into the back row of the packed Calvary Baptist Church. Tate’s aunt, who had driven down from Amarillo, asked if anyone knew who the woman was. Apparently, no one did. The woman left before anyone could talk to her. Then, in the middle of the service, a young man sitting in one of the front rows chanted over and over a single word: “Suicide.”

A few days later, the Childress Police Department, acting on a tip from a high school student, drove to a spot only a quarter of a mile from the hanging tree and found a cow skull lodged in a small tree; beneath the tree were logs surrounding a pile of rocks. The policemen decided that they were staring at an altar. On another night, an officer, driving past the cemetery, saw a figure standing by Tate Rowland’s grave. When the officer came by later to check again, he found spittle all over Tate’s tombstone. Other unsubstantiated reports came in: A cross had been seen burning over Tate’s grave; a schoolteacher’s dog had been stolen and sacrificed.

Was all this the work of pranksters? Kids in Childress, no doubt like kids everywhere, cherished bogeyman tales. Because of one line of dialogue in the 1974 horror classic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre—in which a man, pretending to help a frightened girl, says, “There’s no local phone here. We have to drive over to Childress”—the town had gained notoriety as the home of the actual chain saw killer. That the entire movie was filmed near Austin and was loosely based on an event that took place in Wisconsin didn’t matter. At slumber parties, stories were still told about a killer on the loose. One night, for kicks, Tate had put on a mask and overalls, borrowed a chain saw, removed the chain, and chased some giggling girls into the cemetery.

The stories emerging about Tate’s death, however, were far from funny. When school started that next fall, every high school student seemed to have heard that Tate was a member of a cult and had been killed by fellow cult members because he would not bring them a blond-haired, blue-eyed child to be sacrificed. According to the story, the child was supposed to be either one of his stepmother’s daughters or one of the four blond daughters of his sister, Terrie Trosper. “To make this even thicker,” says district attorney McCoy, “about the same time as these rumors started, we had strangers in cars showing up at the grade school parking lot, trying to pick up little kids. That’s a dad-gum fact!”

No arrest was ever made in the attempted kidnapping case; nevertheless, the information triggered waves of alarm. Tate’s stepmother said she began to receive at least ten phone calls a day from people spreading stories about the cult. “I don’t know if I believe it,” someone would say, “but here’s what I heard …”—and another version of Tate’s death would be born. What seemed initially to be the embellished speculation of high school friends suddenly had turned into a full-fledged community menace. Even though a cotton farmer who had been plowing a nearby field that July day when Tate was hanged told investigators he saw only two boys come out to the hanging tree, then leave and return, the rumors did not stop—and they were coming from citizens the sheriff called “good, ordinary people.” A Childress mother says that just a few days before Tate’s death she saw a group of teenagers in the city park gathering some gravel while a heavy metal song that mentions Satan played from the stereo system of one of the boys’ cars. After they left, she looked to see what they had done. The gravel had been shaped into a perfect circle, and outside the circle was written 666, the sign of the devil. “A shiver went plumb down my spine and then back up again,” the woman recalls.

Childress authorities also received a bizarre phone call from the police department in the Central Texas town of Lockhart. A Childress girl visiting Lockhart apparently told a Lockhart girl that she had dreamed of a boy being hanged by a satanic cult. The Childress girl told the Lockhart girl that she had dreamed that the cult met at an abandoned house with a red porch light in the tiny town of Kirkland, east of Childress. She said that parents were involved in the cult and that they had used a car to run down a boy a few years earlier. The sheriff’s deputies did some checking. Yes, there was a “haunted” house with a red porch light in Kirkland that had just recently burned to the ground. And a couple of years earlier, a fifteen-year-old boy who worked as a dishwasher in a local restaurant had been hit by a car and killed while walking home one night.

On Halloween night 1988, after hearing that the cult, as part of a ritual, was going to dig up Tate’s body to extract his collarbone and pinkie knuckle, a group of eight teenagers met at the gates of the cemetery to visit Tate’s grave. “We thought it would be, well, fun—get some dates, go out there, and see what was happening,” says one of the teens, who was seventeen at the time. According to this young man, who told this very story to a spellbound grand jury, everyone piled into one pickup. He drove slowly toward the back of the cemetery, where Tate’s grave was. As they got closer, someone said, “Is that music?” The teenager stopped the truck so he could hear.

“And then all of a sudden,” he recalls, “some headlights turned on right where Tate’s grave was supposed to be. We all started going crazy, and I whipped the truck around as fast as I could.” As he roared back through the gates, someone noticed pentagrams drawn on the cemetery shed, which started everyone screaming again. The headlights kept coming closer. People jumped out of the pickup and into their cars and took off in separate directions. The young man headed for town in the pickup. He says the lights followed him all the way to the courthouse before finally turning off.

(When I talked to this young man, who was a starting lineman for Childress’ high school football team and is now a burly 240 pounds, he gladly related that story to me—until he realized it would be published in this magazine. “Is this going to be put in print?” he asked. “It is?” His voice dropped to a terrified whisper. “Oh, Lord, the cult’s going to get me for sure now.”)

If that wasn’t enough, soon after the Halloween episode came a “confession” made to the police by Ray Wilks. One of the town’s more renegade teenagers, Ray, then fifteen, was arrested for stealing a car and drunkenly driving it into a utility pole. According to officers, when Ray was booked, he said he was a member of a satanic cult that had been at the tree when Tate was hanged. Those who were at the jail that night would later say that Ray’s voice sounded, in the words of one officer, “very spooky.”

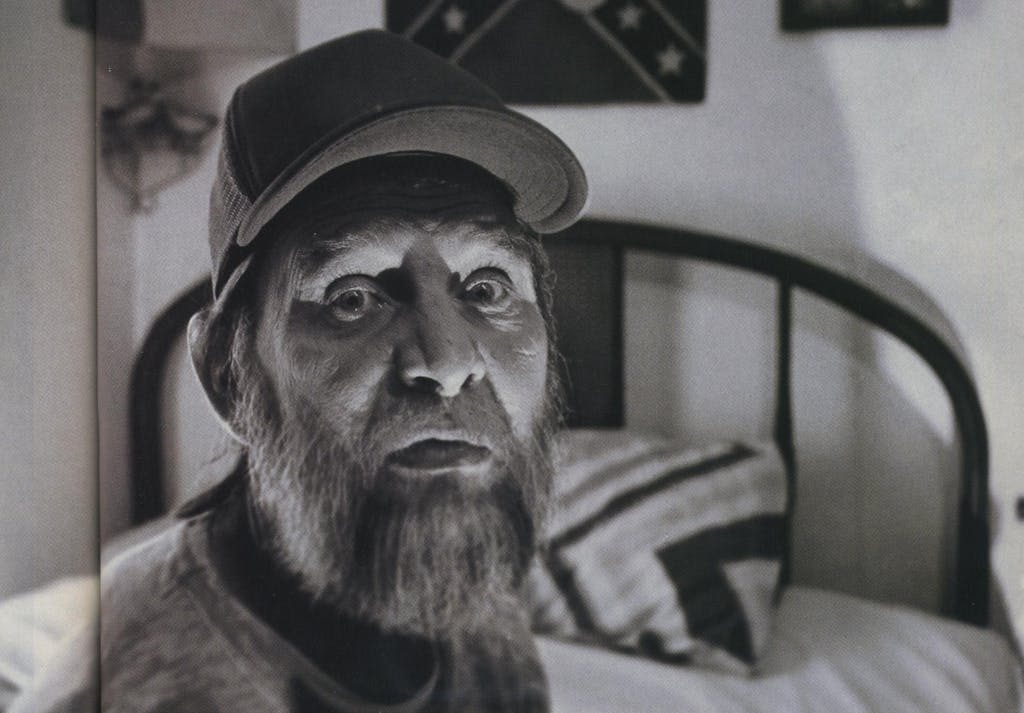

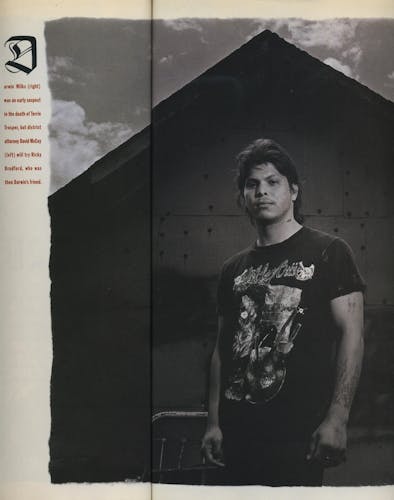

Ray, who today sports a swastika and the words “heavy metal” tattooed on his forearms, denies having been at the tree or having even told the story—“I don’t remember saying anything because I was so drunk,” he told me. Yet the incident got a lot of people thinking about the Wilkses. No strangers to police—David McCoy calls them “a bunch of outlaws”—44-year-old Frank Wilks and two of his four sons had been charged at one time or another with various felonies. Could they possibly be part of a cult? And what were those words that had been painted, then sloppily covered up, on the back of the Wilks home? Curious citizens drove past the ramshackle frame house in the poorer southwest part of town. David McCoy concluded the writing said, “the Devil’s Den” or “the Devil’s Bin.” A courthouse secretary swore it read, “We Worship the Devil.”

“Aw, hell,” says Frank Wilks, an unemployed carpenter with a thick, hillbilly-style beard. “That was the doing of Ray, my youngest son. He was trying to win the affection of a girl, so he wrote, ‘I Love Lettie.’ I said, ‘Ray, you get that shit off the wall.’ So he painted over it, and now everybody thinks it says, ‘I Love the Devil.’ ” Frank says that his two sons living in Childress (the other two live in Dallas) couldn’t have been at Tate’s hanging. “They have the best alibis for that night,” he told me almost proudly. “My older son, Darwin, was in jail, and Ray was being held in a youth detention center.”

Rumors continued to be believed, however, if for no other reason than that they were repeated so often. Kids in town accused one another of being in the cult. Brenda Rowland didn’t believe everything she heard—the mysterious woman in black at the funeral, for example, was an old friend of hers—but she did fuel the fires by calling kids at home and asking them point-blank if they were cult members. Tate’s friend, the bespectacled Clifton Hodges, says he wouldn’t check out a book on the occult at the school library for fear of being labeled a cult member. He was accused anyway. Clifton eventually moved out of Childress for a couple of years, he says, “to get away from all the talk.”

No one’s name was slandered, however, like that of Tate’s old girlfriend, Karen. For a brief period after Tate’s death, a couple of kids seeing her on the drag would hold up their fingers in the form of a cross, as if to ward her away. She was said to have witchcraft books and a Ouija board in her bedroom. According to town gossip, it was Karen who had lured Tate into the cult. One mother in town called Karen the cult’s Queen Bee.

Karen, now 26, is the mother of two young boys. She works at a video rental shop in town and is not unaware of what has been said about her. “My name is smeared everywhere,” she said in a soft voice, sitting one evening on a couch at her parents’ farmhouse, her older son playing at her feet. “I don’t know where it has come from, but I don’t have to listen to that garbage. Childress just wants to believe it because this town has nothing else to do.”

Karen pressed her hands firmly together. “I’m not going to let all the talk hurt me,” she said. “People who know me and my family know that none of this is true.”

One might have thought so. One might have figured, as time passed, that the whole story would finally die down. But then Terrie Trosper showed up dead—and when Childress residents heard where she had died, they couldn’t believe their ears.

Terrie had died in the infamous “devil house” of Frank Wilks.

Masters of Satan?

By all accounts, Terrie Trosper had been going through hard times. She had separated from her husband, had given up custody of her four girls, and had begun running with a crowd that, as one friend delicately put it, “liked to party a lot.” In fact, Terrie’s new boyfriend was a 28-year-old ex-convict named Ricky Bradford, who was then a close friend of Frank Wilks’s 22-year-old son, Darwin. Both Darwin and Ricky had been convicted and sent to the state prison in separate cases of aggravated assault. District attorney McCoy, never one to mince words, says they are “sorry to the core.”

On the night of her death, Terrie, Ricky Bradford, Darwin, and some friends were at the Wilkses’ house, drinking. Frank Wilks, however, was not there: He was in the Childress jail for assaulting a police officer.

Terrie had been drinking heavily—at the autopsy, her blood alcohol level was determined to be .23, more than twice the legal intoxication limit—and according to Ricky Bradford, the two of them went to bed in one of the small bedrooms. At one point, says Ricky, Terrie got up, staggered around the living room, collapsed, and then was helped back to bed. About nine-thirty the next morning, he says, his voice as flat as a fence post, “I just touched her, and she was cold and stiff. I didn’t even look at her. I just got up. And I informed everybody I thought she was dead.”

An autopsy determined that Terrie had died by choking on her own vomit. Officers from the Childress Police Department, finding no evidence of foul play, closed the case. Yet allegations quickly surfaced that Terrie’s death was somehow linked to Tate’s. “She never believed Tate took his own life,” says Lisa Barber, a courthouse secretary and long-time friend of Terrie’s. “Right up to her death, she never accepted it. She was hell-bent on finding out who killed him.” Ricky Bradford admitted to me that Terrie once told him that Tate had warned her to keep her daughters in the house because the cult was going to sacrifice one of them in a satanic ritual. “But I’ve lived here all my life,” Ricky said, “and I’ve never seen any kind of cult.” Ricky speculated that Terrie, depressed over her family situation, was suicidal—he said she had already made one suicide attempt by trying to overdose on pills—and that she probably had tried again, this time successfully.

Although Frank Wilks gave a statement to the police that Ricky once boasted that he was “the devil,” Ricky scoffed at the allegation. “Oh, God,” he said, rolling his deep blue eyes, “I don’t believe in no Satan.” In fact, other members of the Bradford family say it is the Wilks brothers who are associated with devil worship. “I’ve listened to Darwin say that he works for the devil and knows the devil personally,” says Ricky’s sister, Leticia Broom, who is Ray Wilks’s ex-girlfriend. Furthermore, says Ronny Bradford, Ricky’s younger brother, “Them Wilks brothers have been seen wearing black capes and doing Ouija boards and loading goats into a car. I ain’t lying.” Ronny says a group of young men, including Darwin, had once asked him to join them in the graveyard to call up spirits.

Frankly, it’s difficult to believe that capes and Ouija boards and spirit calling would appeal to Ray and Darwin Wilks, two hardass, blue-collar boys who can drink a couple of six packs of beer a night and cheerfully get into fistfights with anyone who just looks at them wrong. Sitting one night in the very bedroom where Terrie was found dead, his arms covered with tattoos that he had gotten in prison, Darwin hand-rolled a cigarette, stuck it in his mouth, and said, “Oh, shit, me and Ray do crazy things when we get pissed off at people. We say we’re masters of Satan, and we say horns are going to come out of our heads. But that’s just having some fun. We don’t believe in nothing. We’re atheists. All these rumors about devil worship in this town is just made-up bullshit by people who are scared.”

Still, something seemed odd about Terrie Trosper’s death. She was the fourth of Jimmie Rowland’s six children to die—one died in infancy of crib death, another died in a car wreck when she was four years old, then Tate and Terrie—and Jimmie and Brenda, whom he married in 1988, demanded an investigation. (Tate and Terrie’s mother lives in seclusion in Childress and does not speak publicly about her children’s deaths.) The former Childress County sheriff, Claude Lane, had adamantly refused to look into the Tate Rowland case, insisting it was suicide—which, in turn, led to predictable rumors that he too was in the cult and part of a cover-up.

But after Lane was sent to jail for dealing marijuana, the case was reopened by the new sheriff, a redheaded, straight-backed Childress-area native named Reece Bowen, and his young deputy, Kevin Overstreet. Both men reinterviewed witnesses. Overstreet traveled to Lockhart to double-check the story of the Childress girl’s dreams. Then, a few weeks after Terrie’s death, there came yet another astonishing twist in the case: Darwin Wilks attempted to kill himself by swallowing 25 to 30 tablets of Elavil, a mild anti-depressant that has tranquilizing effects. He left a suicide note that read, “I know something that the cops don’t know. I know who killed Terrie. I can’t live anymore.” Was Darwin’s note a confession or was he saying he knew the murderer? When he recovered, he said that he didn’t remember writing the note and that he certainly didn’t know who killed Terrie. The sheriff wanted Darwin to take a lie detector test, but Darwin had left for Dallas.

Meanwhile, a forensic pathologist from Amarillo, Dr. Sparks Veasey, had been asked to help with the investigation. He said an autopsy should have been conducted long ago on Tate. After examining the photos of the two rope burns on Tate’s neck, Veasey said it might have determined if Tate had been strangled first and then hanged.

On July 27, 1991, three years after his death, Tate’s body was exhumed from the Childress Cemetery. Autopsy to Determine If Death Was Sacrifice, read the three-column front-page headline in the Index. For the first time, the Satan rumors had gone public, and the area news media came running. One television crew reportedly obtained an interview from a solemn Childress man who said cult members could be seen dancing around bonfires on the banks of the Red River, just north of town. In another interview the boyish-looking David McCoy, a highly excitable yet respected DA who had lost only three trial cases in eleven years, declared that he had received an anonymous death threat. “This is the stuff movies are made of,” he said.

McCoy did release one intriguing piece of information. He said that the boy who was with Tate at the hanging, Chad Johnston—now living in Lubbock—had told a third story to the sheriff. In that statement Chad said Tate didn’t try to hang himself twice. He said that Tate “started jacking around with the rope by swinging around the tree with it.” Chad went behind the car, this time to “take a leak,” and when he came back, he saw that Tate had hanged himself.

Because Tate’s casket was not airtight, his body was too decomposed for Veasey to make any conclusive judgments about the hanging. But an autopsy test did find traces of Elavil: The same drug Darwin Wilks used to attempt suicide. By no means a pleasure drug—“It’s the kind of drug that you would take and then lay down and go to sleep,” says McCoy—Elavil, it was suggested, could have been the very thing a cult would use to sedate someone and then kill him. The rumor mill went berserk.

In September 1991, McCoy convened a grand jury to study the evidence. “Suicide or murder? That’s the question,” the normally staid Index asked with a Shakespearean flair. At the hearing a great deal of gossip was repeated, but little truth came out, because some of the most important subpoenaed witnesses, including Darwin Wilks and Chad Johnston, didn’t show up.

The grand jury did ask that Terrie Trosper’s body be exhumed. Dr. Veasey, after studying the previous autopsy of her death, said it was unlikely that she could have choked to death since she had been lying face down. (The first autopsy had been conducted by Dr. Ralph Erdmann, the embattled Lubbock pathologist who has been indicted on two counts of misconduct.) In front of television cameras and reporters, Terrie’s casket was lifted from the ground. Less than a week before Halloween 1991, the new autopsy results were announced: Terrie had died of asphyxiation, most likely smothering. The report said that contusions on her body, especially on her inner thigh, and bruises in her mouth “indicated blunt trauma, likely incurred during an assault.” McCoy told the press that more than one person may have been involved in her killing—someone held her down while another did the smothering.

There was another thing found in Terrie’s body—Elavil. Though Veasey warned that he could only be 70 percent certain that Terrie Trosper’s death was from murder, McCoy vowed that he would pursue the case as a homicide.

At that point, it was hard to find anybody in Childress who did not believe a cult was on the loose. The more the rumors were mentioned, the more they grabbed the imaginations of the townspeople. Word spread that the cult had been seen meeting at a mobile home factory or a dry cleaning store, that a baby lamb with its heart cut out had been found near a cotton gin, that a Childress man had showed he had the powers of Satan by pointing at a cat and commanding it to die. When the First Baptist Church in Childress presented a satanism seminar, more than 450 residents listened intently as an occult expert told of cults’ luring teens with heavy metal music and teaching them to dig up coffins at the cemetery and have sex with the bodies.

As fear swept the town, the grand jury reconvened. Darwin Wilks still could not be found, and Ricky Bradford did not appear, but just about everyone else did. Regarding Terrie’s death, it was learned that the Elavil probably came from Frank Wilks’s elderly father. Frank himself took the stand to say that Darwin told him that Terrie had been murdered by another person in the house that night. But no one who was at the house would confess to anything.

Outside the grand jury room, tempers flared. Brenda Rowland got into a shoving match with Brenda Stokes, the sister of Terrie and Tate’s mother. Brenda Stokes accused Brenda Rowland of hitting Tate and Terrie when they were alive. “You better quit lying on me,” replied Brenda Rowland, and they started pushing each other around.

Then most of the Hackler family arrived at the courthouse to clear their names. Karen’s younger sister testified that on the day Tate died, he had called the Hackler home and said he wanted to kill himself. And Karen said she knew nothing about a cult. When the Hacklers emerged from the grand jury room, the girls’ father, James Ray, wearing a big white cowboy hat, angrily thrust a briefcase at a photographer trying to take a picture of his family.

A stocky Chad Johnston arrived, repeated his third hanging story and stuck to his claim that Tate’s death was suicide. According to McCoy, “Chad’s testimony was that Tate thought Karen was messing with his mind and that Tate got sick of it. And Tate thought he could make her feel sorry.”

So why was there a second rope mark on Tate’s neck? Chad couldn’t—or wouldn’t—say. Who killed Terrie Trosper? McCoy could only reply, “We’re one witness away from knowing that.” The grand jury ended its work with just as many questions as answers.

Witch-hunt

For four months, that’s where the matter stood. Then, this past March, the case broke wide open again. Frank and Darwin Wilks arrived at the sheriff’s department to say that Ricky Bradford had admitted at a barbecue at their home the previous night that he had killed Terrie. The Wilkses alleged that Ricky had threatened to kill them if they snitched. Darwin said Ricky had become provoked by questions about Terrie’s death. According to Darwin, Ricky had said, “Yes, I killed the bitch,” and then threatened to burn down Frank’s house and cut out Darwin’s eyes if they told. Based on the new information, the sheriff arrested Ricky for first-degree murder.

Ricky, insisting that he had said nothing about killing Terrie, claimed Darwin had set him up. Ricky said Darwin was broke, and by making his statement about Terrie’s murder, Darwin knew he could get the $1,000 reward that the sheriff’s department had been offering. (The sheriff’s department confirmed that Darwin had been given the reward money.) In fact, Darwin did admit to me that he had been worried that the police were going to arrest him. He said he had finally submitted to a lie detector test a few weeks before Ricky’s arrest and had flunked when asked by the examiner if he had smothered Terrie. “The cops were trying to frame me,” Darwin said. “But, hell, I was asleep that whole time she was supposed to have been killed. I couldn’t have smothered anyone.” After Ricky’s arrest, Darwin took another polygraph test and passed it.

In truth, no one seems convinced that the latest turn of events clears up Terrie’s death. David McCoy admits that with an inconclusive autopsy and a list of unreliable witnesses, he doesn’t have as strong a case against Ricky as he would like to have. He says that before going to trial sometime this summer, he wants to give lie detector tests to all the witnesses. “Ricky Bradford is a sorry individual,” McCoy says, “but I don’t want to send him to prison just for being sorry.”

What the latest publicity about the Trosper case has triggered, of course, is a rash of even more satanic rumors and cult sightings. A few days after Ricky’s arrest, for instance, a white cat with its heart cut out was found on a road outside of town. Sheriff Bowen and his deputy dutifully went out in the squad car to take color photographs of the dead animal. “I don’t know what it means,” says Bowen, shaking his head slowly, “but it’s got to mean something.”

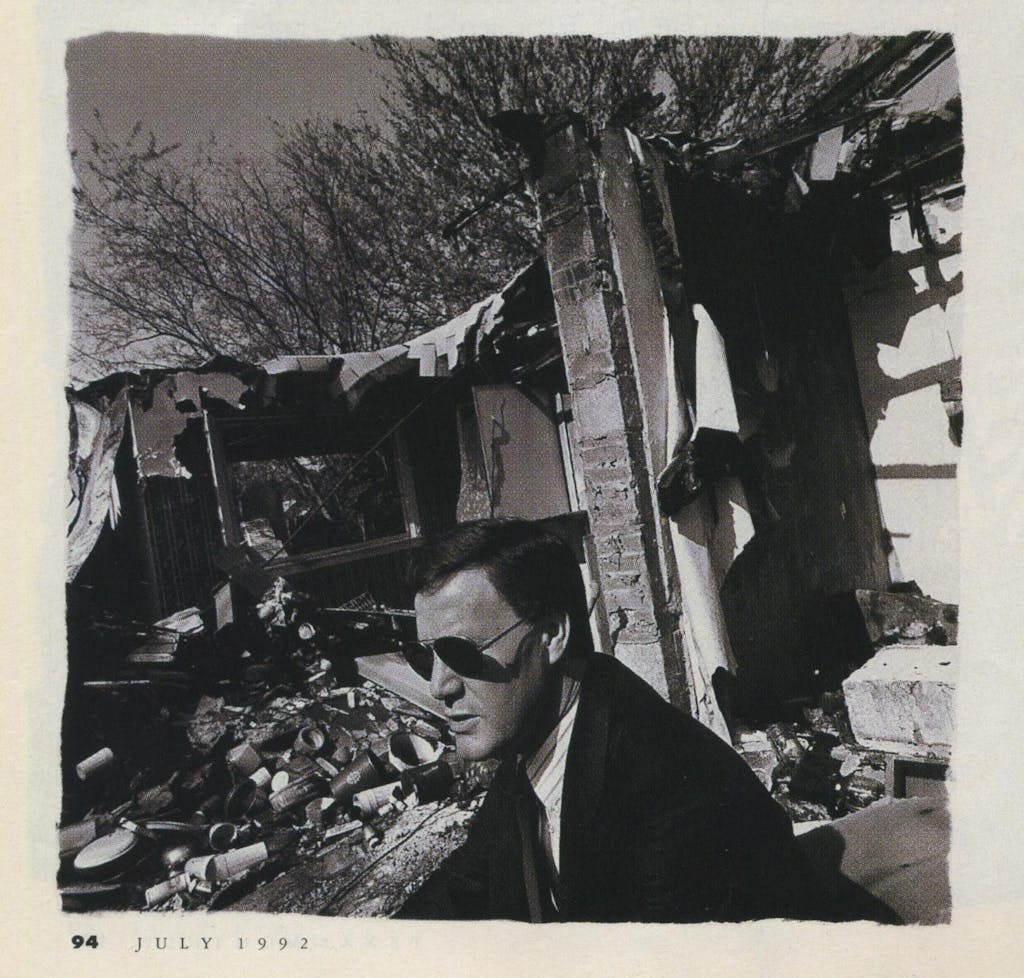

Then, just before Ricky’s murder charge went to the grand jury, David McCoy’s house mysteriously burned to the ground. The fire marshal said the fire was accidental. “But the first thing I thought was that someone was after me,” McCoy says. “I still wonder if that’s not what happened. Anything can be made to look accidental.”

A few weeks later, a middle-aged couple was found in possession of strange works of art. Some were pornographic, and some were interpreted as, well, satanic. In one, a devilish goat’s head was drawn over a human body; in another, an outline of Texas was drawn inside an emblem that looks like a pentagram. Also found in the house was a thick metal rod that McCoy describes as “some kind of staff that the priest of a [cult] organization is supposed to have.”

Such publicity has certainly damaged Childress’ image. One woman from the nearby town of Quanah stopped by the Childress County courthouse and asked if it was safe to drive down U.S. 83 at night, considering that’s where the cult allegedly worshiped. An Amarillo reporter covering the story wouldn’t come to Childress without carrying a gun. “We all feel violated by the attention,” says Nancy Garrison, a rancher’s wife and the district clerk at the courthouse. “There are kids in Childress doing great things, really great things. They’re not in cults.”

In fact, to this day, not one person in Childress has confessed to membership in a cult. Nor has Sheriff Bowen or his deputy been able to find any concrete evidence that a satanic cult ever operated in town. In the end, Tate’s death might have truly been one of those tragically impulsive suicidal acts of youth. Terrie’s death, while possibly a murder, was more likely due to personal problems than supernatural ones. Was there truly a satanic menace—or was it all a hoax, a haunting twentieth-century reminder of the days of the Salem witch trials?

It will be a long time before some of the families, like the Hacklers, put their lives back together. “We lived in this county all our lives,” says James Ray Hackler, who blames McCoy for taking advantage of Tate’s death to get publicity for himself. “We’re victims of lies.” The Rowlands, who still aren’t speaking to the Hacklers, say they too are victims—their children dead, and no one to account for it. “There must have been something to this,” says Brenda Rowland, “or else these rumors wouldn’t have all gotten started. Rumors don’t get started on nothing, you know.”

A few people, targets of the rumors, have moved on to other towns. The Bradfords and Wilkses don’t plan on leaving, despite the blight on their reputations. Darwin Wilks’s young girlfriend has just given birth to their first baby, “but every time she goes out of the house just to go someplace like the grocery store,” he says, “people make her cry by saying, ‘Oh, you’re the one who had Satan’s child.’” (Darwin, incidentally, has left his girlfriend and plans to remarry his ex-wife.)

As for Frank Wilks, no one is hiring him even for part-time farm work. “People won’t have nothing to do with me,” he says. “When I get near them, they step back and say, ‘Don’t you put a spell on me.’”

But Frank takes a philosophical view of his troubles. One evening, he was out drinking at the VFW hall with one of his girlfriends—“A lady who the whole town thinks is a high priestess just because she’s seen with me,” he says. Another woman approached and told them her boyfriend had a skin rash. Did he and his girlfriend have any kind of magic potion?

According to Frank, his girlfriend went into the bathroom, poured some calamine lotion in a glass, walked back, and said, “Rub this all over him, and it will go away.”

“It worked,” Frank says, “and the old gal later thanked us. So, hell, maybe something good came out of this mess after all.”