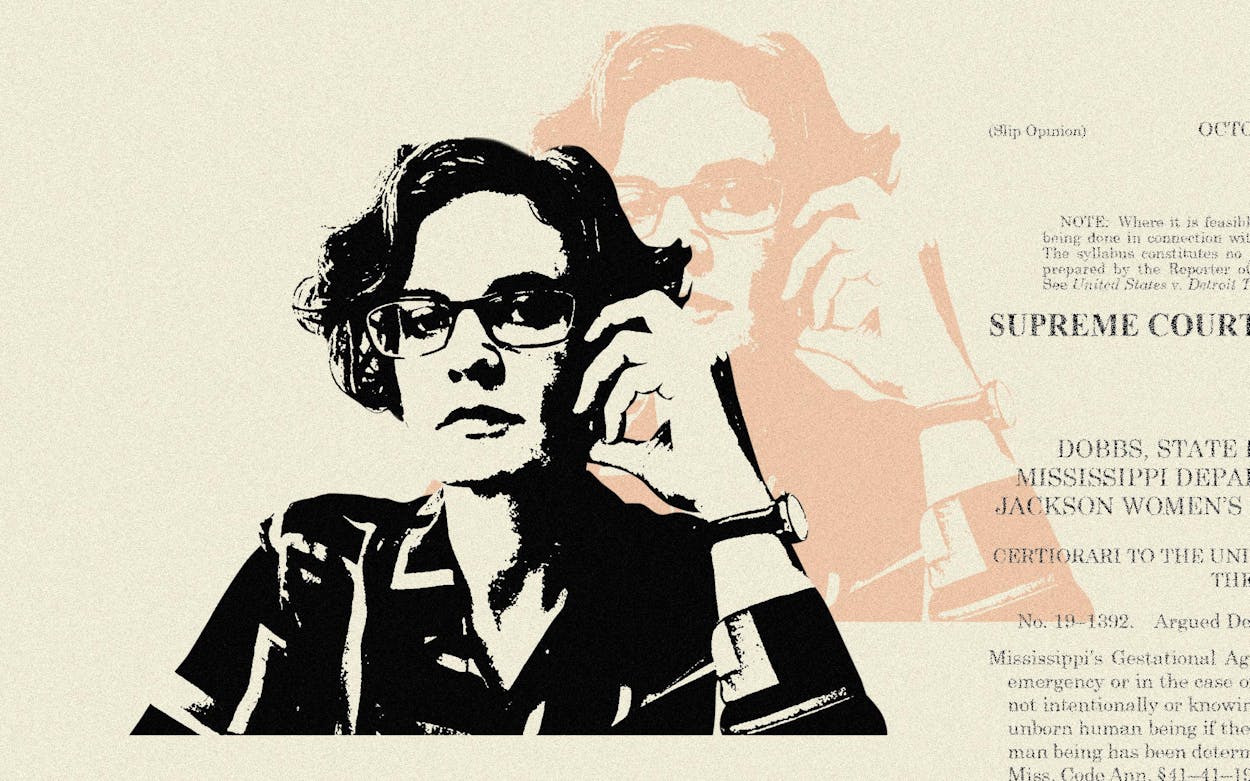

When Merritt Tierce became pregnant at age nineteen, she was a student at Abilene Christian University who had hopes of attending graduate school. Instead, she was pressured by her Southern Baptist family to marry and become a mother. The tumultuous decade that followed inspired Tierce’s breakout 2014 novel Love Me Back, which features a young mother who has left her marriage and her faith and found a refuge of sorts in the hard-partying Dallas service industry. Tierce herself waited tables for many years.

In addition to writing one of the best Texas novels of the twenty-first century, Tierce helped found the abortion nonprofit Texas Equal Access [TEA] Fund, has earned TV writing credits on HBO’s Orange Is the New Black, and penned perhaps the most talked-about magazine piece on abortion in recent years: “The Abortion I Didn’t Have,” which appeared in the New York Times Magazine in December 2021. In that essay, Tierce confronts rarely voiced feelings of regret about carrying a pregnancy to term. She steers the piece toward a complex conclusion: “I love my son, and I am not at peace with the sacrifice I was required to make. I look at him at twenty, the age I was when he was born, and I love him so much I would never think of telling him he must have children now.”

Because of her experience with an unplanned pregnancy in a world in which abortion did not feel like an option, and because of her many years as a service-class mother bottling up her anger at a system that she increasingly came to understand as having failed her and oppressed her, Tierce is a writer who speaks fiercely to the present moment. Those of us still trying to wrap our heads around the ways the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent abortion ruling will play out in ordinary Texans’ lives are well-advised to seek out her nuanced, soul-searching, and very funny storytelling. In the immediate aftermath of the ruling, Tierce spoke with us about her work.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Texas Monthly: Before we get into the Roe v. Wade reversal, let’s start with a quick story. When you worked at a high-end restaurant, you waited on Rush Limbaugh, is that right? What was that interaction like?

Merritt Tierce: It was weird. That job was my livelihood, and it was really emotionally and psychologically compromising in every way. It’s not my scene. It’s a misogynistic, old-school, boys-club-type place. When I started working there, the culture was obscene.

TM: It was a place where Rush fit in.

MT: Exactly. I put on the uniform and I played the role every night, even though it wasn’t what I believed. I was working at the TEA Fund at the same time that I was working at the restaurant. Those are polar opposite institutions—one is this grassroots radical feminist thing, and one is entrenched in all kinds of patriarchal institutions. I had a lot of whiplash built into my life.

I’m saying this because I feel defensive and ashamed about having even agreed to wait on Rush Limbaugh. But I was just like, “This is my job, this is how I pay my bills and feed my kids.”

It was a small table, and their bill was only $300. He tipped me $2,000, which is a show of largesse and power, and also very generous. I didn’t know what to do with that money. I felt like, “This is crazy. This is blood money.” I think I used part of it to get my car fixed. And then I donated some of it to the TEA Fund. I didn’t know what to do with it to make it somehow okay.

TM: You’re a writer who seems to have so little concern for taboos, both in the way you discuss your personal abortion choices in your nonfiction and in the way you write candidly about sex and absentee motherhood in Love Me Back. How do you think that squares with your years as a waiter, holding things back? Do you think that restraint contributed somehow to the outspokenness of your writing?

MT: It didn’t start there. Yes, [at the restaurant] I was playing a role and observing everything. I was seeing it and participating in it and then being like, “Oh my god, what is this?”—then going back and doing it again the next night. So yeah, writing about it and being as honest as I could about it was a way to square up realities for me.

But I think it goes back way further than that particular dissonance. It goes back to Christianity, being raised in that religion and being taught all kinds of things that I discovered through personal experience are harmful and not true. At some point you have to say, “Wait, someone’s messing with me here. This isn’t the truth. Either what I’m experiencing is not real, or what you’re saying about reality is not real.”

TM: Writing plainly about things like abortion can also expose a writer to backlash. Is that something you’ve experienced, from either the essays or the novel?

MT: For sure. Everything I’ve written about abortion, people have sent me hate mail and told me I shouldn’t be a mother, et cetera. The thing with Rush happened at least five or six years before the book came out. I only told a couple of people about it. But one of those people was friends with a journalist, and when my book came out he asked me about it. That’s how the story became public. And then Rush Limbaugh’s fans ganged up on my Amazon reviews and aggressively tanked them by giving me a bunch of one-star reviews.

TM: Oh, God.

MT: There’s always negative fallout. But I was actually really interested in the response to the essay that I wrote for New York Times Magazine. It was definitely the most widely read piece I’ve ever published, by far. And yet I didn’t get almost any hate mail. I heard from everyone I’ve ever known, and all kinds of strangers thanked me for writing.

I think it helps that I’m not on social media. I don’t know what it would have been like if I were on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook, and people could have attacked me there. That probably had an effect.

But the people who wanted to thank me found me, and I didn’t get the hate mail that I usually get. I think that’s because it was a piece that was about the complexity and nuance that is usually missing, and it was just harder to attack. And partly because I had the baby. I didn’t have the abortion, and I say I couldn’t have considered abortion, though the implication is that I wish that I could have.

TM: What kinds of people were reaching out to thank you?

MT: It was a lot of people saying, “I didn’t know how I felt about my experience until I read what you wrote.” It was so many heartbreaking messages of women who had experiences like mine before abortion was legal, or experiences just like mine, and never recovered from it. And lots of echoes of one of the main statements of my piece, of women writing to me and saying, “I love my kids so much, but—.”

TM: How are you doing these past few days, since Roe was struck down? What has been your thought process?

MT: I feel scared. I mean, I’ve been expecting this. Four years ago, when Anthony Kennedy retired, that was when my blood ran cold. I thought, “Oh, it’s just a matter of time now. It’s just the number of justices. We don’t have it anymore.”

But the final actual fact of it, it feels very hateful, and it feels so ominous. I really don’t think you can overstate the impact of this, not just on women and bodily autonomy and people who need access to health care. Beyond that, politically, it’s an earthquake.

TM: Do you have a message for others about how to think about this new reality? Or are you still in a moment of absorbing the change?

MT: I think the message is, “Take the time you need to feel the shock of this,” but it really is critical for everyone to do whatever they can. Look to the reproductive justice organizations that already exist, like the TEA Fund, and the National Network of Abortion Funds, and the Afiya Center in Dallas—these are all organizations that have been on the ground protecting these rights and putting themselves out there as the targets for this very racist, sexist lawmaking for a long time. Don’t start new organizations, fall in with what these organizations are doing. Respect that work and learn from them. They’re there, and they need all the support they can get.

TM: You come from a conservative, religious background. Thinking about the other side, the communities of faith that are driving the anti-abortion movement, do you think their faith will be tested by a new post-Roe reality? Do you think that, say, people you knew growing up are prepared to see some of the draconian ideas that are being thrown around actually put into practice?

MT: No, I think people believe what they want to believe, and they continue believing it in the face of contradictory facts and realities. People hear heart-wrenching stories and chalk them up as exceptions, as one-offs that don’t need to be thought about as indicators of, you know, any larger change that needs to happen in their own beliefs.

We have become so polarized that it’s very difficult for people to grab onto ideas outside their own realities. But I think there is a deep hunger for that. I don’t know how we work toward it, except by telling more complicated stories and refusing the black-and-white absolutist positions that we keep being offered—mainly by, you know, the internet and by politicians.

People don’t feel free to speak openly about complexity or nuanced feelings. People who support the right to abortion do not feel free to say, “I had an abortion, and I feel really f—ed up about it.” They feel like they have to support the right to abortion unequivocally. And people who don’t support the right to abortion don’t feel like they can say, “I had an abortion, and I don’t feel good about it, but it was what I needed to do.”

People don’t feel free to voice these nuanced perspectives because you can be taken down in the public court immediately. There can be real-world repercussions for your job and your family. It’s an increasingly hostile feedback loop.

TM: I read Love Me Back as the story of someone struggling—mostly failing but struggling ferociously—to find some kind of autonomy and independence after being asked to submit to a basically patriarchal system. The protagonist breaks free of family life, not without deep, self-mutilating feelings of guilt, and finds a modicum of financial independence waiting tables on, well, hideous men.

MT: [Laughter.]

TM: Do you think Marie is just as stuck at the end of her timeline as she is in the beginning? Or do you see her as a character on a hopeful trajectory?

MT: That was the question I decided to leave the work on. Is she going to stay stuck in this world? Or is she going to break out of it somehow? I didn’t want to write any kind of contrived, salvific thing for her. I feel like we see that a lot in fiction. But as one of my favorite professors in grad school said, “When was the last time you changed?”

It’s true and it’s not true. People change all the time. That book is based on autobiography, and I did leave that world behind. But it took a lot of work to break out of it. What I let be evident in the book, I hope, is that she is slowly cobbling together more self-awareness, at least becoming less naive and honing her observational powers. So there is some movement happening over the course of the years [at the restaurant]. I guess that in itself suggests that maybe she will find a way toward a better life. But it’s not guaranteed.

TM: Since Orange Is the New Black ended, you’ve been trying to make a television show about abortion, pitching ideas in Hollywood. What has that been like?

MT: It has been really frustrating. Hollywood is weird. It has a reputation for being very progressive and supportive of abortion, but what I encounter over and over is people who are just really scared of abortion. I’m talking about executives and studios.

I think it’s because there has been such a consistent collective suppression and stigmatization of abortion stories, forever. You just say the word “abortion” and people cringe. I have to get past those emotional defenses before I can even talk about how rich and important I think an abortion show could be. I get a lot of resistance that is just completely unsupportable—people being afraid of abortion because it’s a downer, or it’s grim or whatever. I’m just like, what about Dopesick? Zombie shows? Every show you turn on, people are murdering each other.

People misunderstand it as, “Oh, an abortion story always has to be sad or traumatic.” That’s not the reality. The reality is that the challenge for a TV writer or a dramatic writer of any time is that the most common abortion is not traumatic. It’s early in pregnancy, it’s someone who can’t afford another child, it’s someone who already has kids. And there’s not that much more to it. Medically, it’s one of the simplest, most uncomplicated, safest procedures ever. It’s so anticlimactic. I think that’s why there’s this warping effect, where the stories that are more traumatic, like rape, incest, fetal anomaly, pull more focus in the media, because they’re inherently more dramatic. But that’s not the reality of abortion.

So, if you want to tell the real story of abortion, it has to be more about the characters and more about the context in which they’re making this decision, more about their lives. I think that’s great for any kind of storyteller. You can never run out of abortion stories, because all kinds of people have abortions, for all kinds of reasons. And they feel all kinds of ways about it. But until there’s a whole show about it, you can’t represent that. That’s what I want to do.

I have said this spiel to so many people out here [in Hollywood], and I think there still is just such a strong fear of abortion. When people hear the word, they just automatically imagine a mangled fetus. And that is how the anti-abortion people have won. They have controlled the story. They’ve made it not about women and pregnant people making choices about their own lives, and making choices out of love for the children they have, and making choices about what kind of family they want to have. They’ve made it about the mangled fetus. And you can’t get past that.

- More About:

- Abortion