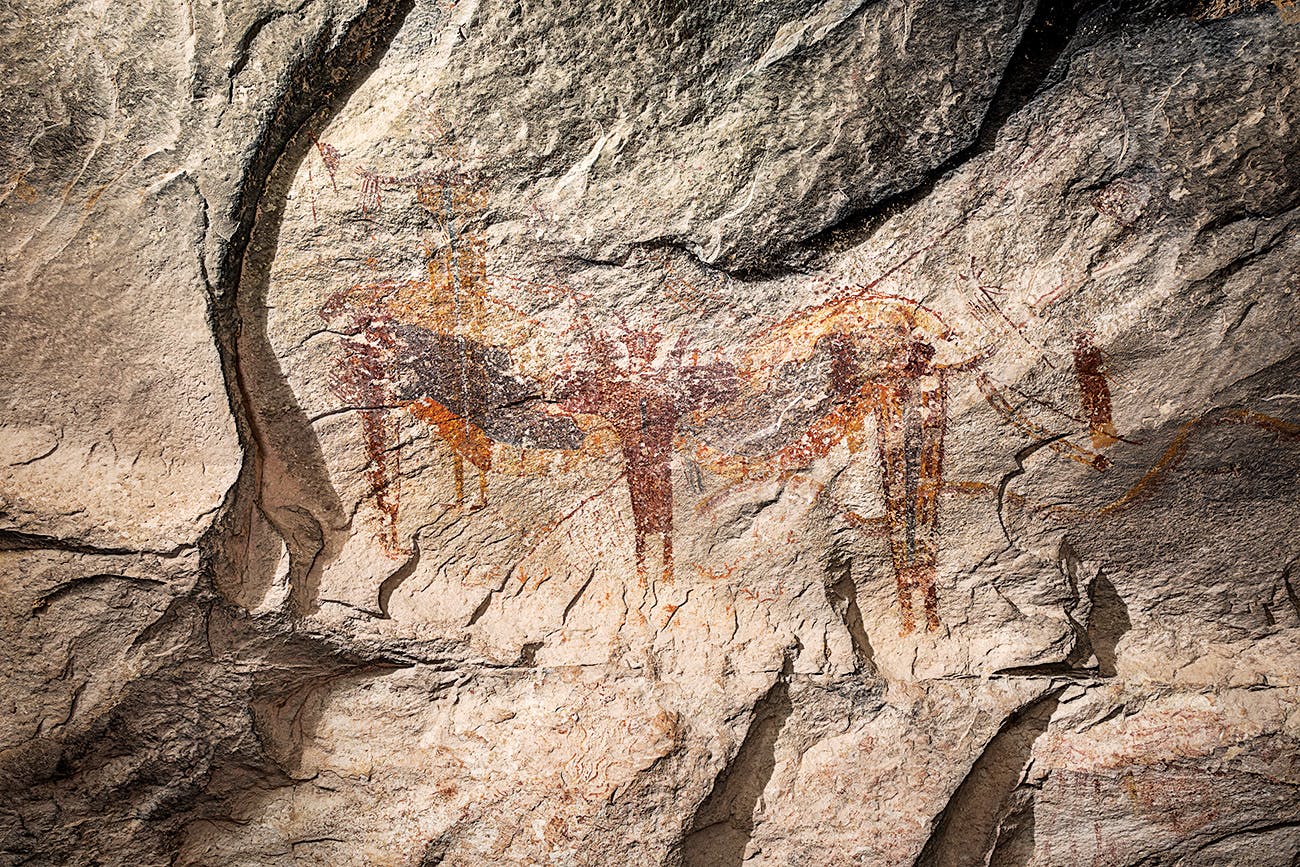

On a hot fall morning, four archaeologists bushwhack through vines of shin-shredding catclaw and scramble up a rocky ridgeline at Devils River State Natural Area, in West Texas. There, high above a valley, a few miles from the river, they unload packs of camera gear and laptops, ready to spend the day focusing their attention on a series of dark red lines and shapes painted along the cliff wall, behind a narrow ledge. A cluster of four humanlike figures covers one small area, and depictions of what look to be spears are a few feet away. Unidentifiable patches of paint are scattered across this section of rock, and in a few places the stone is scored with fine lines, as if someone tried to etch a pattern. The limestone under the art is spalling in places. Bees have built a nest on the wall, and scrappy plants are sprouting all around the area.

A sense of mystery clings to the rocks as well. Although carbon dating indicates the pictographs were painted by prehistoric indigenous peoples between 1,450 and 4,200 years ago, experts don’t know much else about this location, also known as site 156 of the Alexandria Project, a four-year effort to archive the rock art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands using high-resolution photography and 3-D imaging.

“We’re in a race against time,” says Jessica Lee, the executive director of the nonprofit Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center, based in Comstock, which studies rock art in this hardscrabble corner of the state (Comstock is just nine miles from Seminole Canyon State Park, home to some impressive pictographs). In 2017 Shumla launched the Alexandria Project, with the goal of digitally documenting and cataloging the paintings, no matter how fragmented, by the end of 2020, before nature (especially flooding and humidity), animal activity, and vandalism take more of a toll. Private donors have helped Shumla raise much of the $3 million needed to finance the research.

The project draws its name from ancient Egypt’s Library of Alexandria, which, according to legend, contained more than 700,000 books and scrolls before being destroyed by fire two thousand years ago. The Shumla staff compares the rock art murals in southwest Texas to a library of volumes filled with cultural knowledge. “Every single one of these panels is like a book that holds different information,” Lee says. “It’s kind of like an encyclopedia—if you lose S and V and E, that information is not in the other books. We are fighting to save the books in our ancient Texas library.”

In the Beginning

Shumla founder Carolyn Boyd theorizes that the White Shaman mural depicts the birth of the sun, which would make it one of the continent’s oldest creation narratives.

Some of the region’s artwork is well known, including the White Shaman mural, a four-color collection of pictographs on a rock shelter a few miles from where the Pecos River meets the Rio Grande. Artist-turned-archaeologist Carolyn Boyd, who founded Shumla in 1998, first encountered the site in 1989 and spent the next three decades researching and analyzing the painting using laser mapping, high-resolution panoramic photography, and portable X-ray fluorescence, among other tools. In 2016, Boyd, who is now a professor at Texas State University, published her team’s findings in the book The White Shaman Mural: An Enduring Creation Narrative in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos.

The Alexandria Project applies the latest technologies to the methods developed by Boyd and her colleagues to rapidly document the state’s vast rock art tradition. When it began, Shumla staff expected to tackle about three hundred rock art sites (the majority of them on private land) in Val Verde County, knocking out one or two each week. Along the way, though, archaeologists have stumbled upon nearly twenty previously unknown or unreported rock art locations. They’ve also added to their workload the task of writing site summaries to share with the landowners who allow the archaeologists access to private property. They now aim to document 225 sites by the end of this year.

Back at site 156, at Devils River, the team will spend two days gathering as much information as possible. “We’re limited in the time we can spend. The data we collect here gives us a baseline,” says archaeologist Jerod Roberts. “Some of the sites could last another month or two—whenever the next flood comes. Some will last another five thousand years.” He aims a camera at a rocky wall, adjusts a few settings, and steps back. The camera snaps photos automatically, one after another, the lens moving a few millimeters after each take. Individual images can be stitched together into a panoramic shot that researchers can zoom in on for detail, or they can be used to create a 3-D model. “It gives us a glimpse into the past we haven’t seen elsewhere,” Jerod says.

Nearby, another researcher, Vicky Roberts, who is married to Jerod, crouches in the gravel, gazing into the overhang as she types notes into her computer. Veins of hard, shiny chert run through the cliff wall, and chip marks indicate that someone long ago harvested it, probably to make tools. But no matter how intensely she looks, she’s well aware that not everything is visible.

Some of the site’s secrets may be revealed later. The archaeologists use a special method called decorrelation stretch to enhance colors in the photos of the paintings, drawing out images not easily apparent to the naked eye. “Sometimes we won’t see things in the field, but when we get to the lab and enhance it, we see painted figures,” Vicky says.

Lee, the executive director of Shumla, calls the eight-thousand-square-mile stretch of canyon-spliced land where the researchers have focused their work one of the most significant archaeological regions in the United States. “In my view, this region is as significant as any Old World archaeological site, like Stonehenge or the Sphinx,” Lee says.

As the team documents the sites for the Alexandria Project, they prioritize them based on research potential, threatened status, and clarity of the art. “We’d love to focus on one site at a time and study it for five years, but we have a duty to preserve these sites,” Lee says. “We want other people to be able to research these now and forever.”

Some sites have already been destroyed. Cliff walls that were once adorned with rock art now lie submerged beneath the surface of the Amistad Reservoir, created in 1969. “At the time, they did not recognize the significance of rock art sites,” Lee says. “One of the things that is so unbelievable about this rock art tradition is the amount of time and resources that had to be expended to create sites of this magnitude. It’s amazing for a hunter-gatherer society; you really have to believe art is pivotal to your survival to expend the calories and time to create it.”

The Alexandria Project shows how consistent the rock art motifs are throughout the region. Archaeologists believe that every detail, from the addition of antlers to an anthropomorphic figure to the number of its fingers and its color, has meaning. “The art is certainly beautiful, but what really astounds me is the complexity of the belief system they were able to depict,” Lee says. “It’s easy to assume we’re so much more advanced than they were four thousand years ago, but this art is evidence to me that it’s just not the case.”

Three Ways to See Prehistoric Pictographs in Person

White Shaman mural

The White Shaman mural stretches 26 feet across a rocky overhang within view of the U.S. 90 bridge northwest of Del Rio. Vibrant images of a white-robed figure with arms stretched wide, humans, animals, and otherworldly creatures, along with lines and dots in black, yellow, red, and white, brighten the stony recess above the Pecos River. The Witte Museum, in San Antonio, owns the site and offers public tours of the White Shaman Preserve at 12:30 p.m. every Saturday from September through May. Tours are limited to groups of twenty, age twelve and up. Cost is $15 ($10 for museum members). The Witte also offers occasional tours of other rock art sites, including Halo Shelter, Curly Tail Panther, and Meyers Springs.

Seminole Canyon State Park

Visitors to Seminole Canyon State Park, in Val Verde County, can also see spectacular examples of pictographs. The park offers ranger-guided hikes to the Fate Bell Shelter (pictured above), protected by a huge cliff overhang. Tours are $8 for adults and $5 for children age five to twelve. During winter and spring, visitors can also sign up for a $25 daylong backcountry hike to rock art sites in more-remote areas of Seminole and Presa canyons. Half-day hikes to rock art sites in the upper part of Seminole Canyon are offered in the spring and fall for $12.

Hueco Tanks State Park

Hueco Tanks State Park, in El Paso County, also offers examples of rock art. Visitors can make reservations to check out the self-guided area of the park for $7 or sign up for a ranger-guided tour to see pictographs and petroglyphs for $9.

This article originally appeared in the January 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Our Rock Art Library.” Subscribe today.