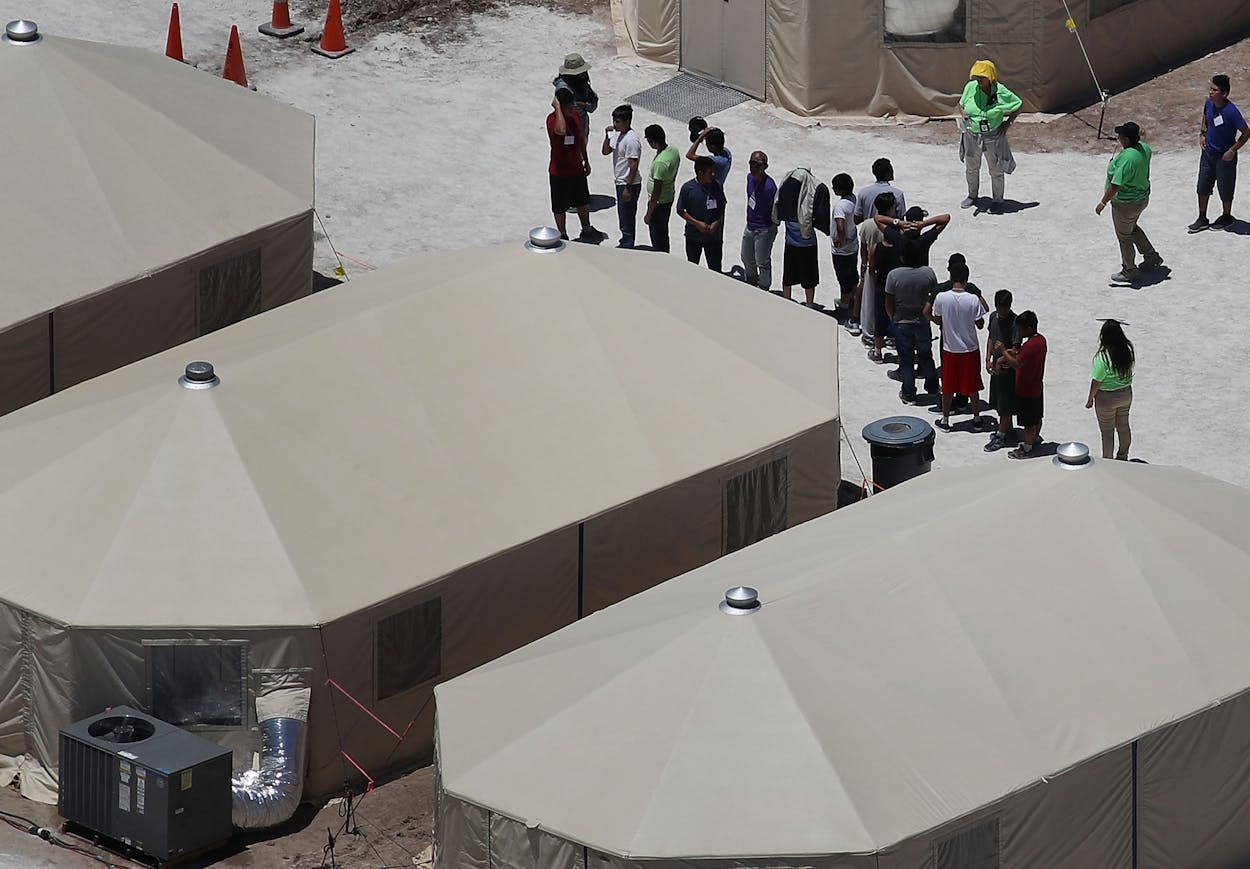

The private operator hired by the federal government to run a tent facility housing 2,700 migrant children in El Paso County is considering not renewing its contract with the government unless the Trump administration agrees to change its policy and make it easier to place children with relatives, Representative Beto O’Rourke said Saturday. He was part of a five-member Democratic Congressional delegation that toured the facility in Tornillo that has become the symbol of what may be the largest U.S. mass detention of children not charged with crimes since the World War II internment of Japanese-Americans.

O’Rourke said Kevin Dinnin, the chief executive officer of BCFS Health and Human Services, a San Antonio-based nonprofit that operates Tornillo under a contract with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told the delegation he is considering ending the contract after December 31 if the Trump administration won’t agree to change fingerprint requirements for people seeking to sponsor children housed in Tornillo and other government facilities across the country.

“He said he’s caught between a rock and a hard place because he doesn’t think that the policy is right,” O’Rourke said of his discussion with the Tornillo contractor. “He doesn’t think this is the right way to do it, but he doesn’t—in his words—want to abandon the kids. I asked him what happens to these kids if the contract is not renewed at the end of December and he said, ‘I don’t know,’” O’Rourke told Texas Monthly, adding that HHS representatives also said they didn’t know what would happen to the children if BCFS ended the contract.

The key issue is a policy that began in June requiring potential sponsors of what the government calls “unaccompanied alien children”—those apprehended at the border without a parent or guardian—to submit fingerprints of all adults in their household, which are turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials for review. Since that policy took effect, the number of migrant children in government custody has mushroomed from about 9,000 to almost 15,000.

BCFS spokeswoman Evy Ramos declined to comment about O’Rourke’s remarks on Saturday. She told Texas Monthly on Thursday that the nonprofit hasn’t yet reached an agreement with HHS to extend the contract after the end of the month. A source familiar with the contract extension discussions said BCFS officials have tried to make an extension conditional on modifying the fingerprint requirements, which would hasten Tornillo’s closure and sharply decrease the numbers of children in government custody. The source asked not to be identified because he or she wasn’t authorized to speak publicly.

Health and Human Services spokeswoman Evelyn Stauffer declined to comment on whether the agency has considered ending or otherwise changing fingerprint requirements. “As you know, the safe and timely release of (migrant children) to suitable sponsors is one of the primary goals of the program. We are always seeking to ensure a child’s safety without undue delay as part of our internal deliberative process,” Stauffer told Texas Monthly.

‘Shocked and outraged’

The Democrats who toured the Tornillo tent facility on Saturday included senators Jeff Merkley of Oregon, Mazie Hirono of Hawaii and Tina Smith of Minnesota, and representatives Judy Chu of California and O’Rourke, the El Paso congressman who leaves office January 3. “I am shocked and outraged by what I saw in there. There are 2,700 children ages 13 to 17 who are in essence locked up there in a child prison and could be released had it not been for the change in Trump’s policy,” Chu said.

The cost of housing unaccompanied children has exploded as the population of migrant children in government custody swelled to a record 15,000, up from 3,000 when President Trump took office. The Trump administration earlier this year transferred almost half a billion dollars from other HHS programs—including cancer research and Head Start—to cover rising costs for fiscal year 2018, which ended September 30. Recently, the administration asked for an additional $190 million on top of the $1.3 billion already budgeted in fiscal year 2019, something one leading House Democrat said would happen “over my dead body.”

Ramos of BCFS told Texas Monthly earlier in December that HHS has spent $144 million to house children in Tornillo between June and November—which amounts to about $1 million a day. That amount likely has grown to about $2 million a day in December because of the growing population at Tornillo. BCFS owns the tents and other infrastructure at Tornillo, and congressional officials in the past have told Texas Monthly that it is the only organization in the country that has the resources to operate such a facility.

New fingerprint policy

In June, the administration began implementing a memorandum of agreement between the departments of Homeland Security and Health and Human Services, in which the agencies agreed to share data on migrants. One major change impacted migrant youths apprehended at the border without a parent or guardian. Such children are placed in the custody of an HHS agency called the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which houses them while searching for sponsors, usually a parent or other relative already in the United States. ORR historically has been a child welfare agency; the memorandum of agreement made it part of the government’s immigration enforcement apparatus.

The agreement required any potential sponsor to submit his or her fingerprints, as well as fingerprints of any adult in the household, for review by ICE. Previously, parents or legal guardians seeking to sponsor a child were only required to submit fingerprints if there was a “red flag” in a background check that indicated a possible threat to the child, said Mark Greenberg, who oversaw the sponsor-placement program at the end of the Obama administration. If a relative other than a parent or guardian sought sponsorship, he or she had to submit fingerprints, but there was no requirement for fingerprints of other adults in the household.

The administration said the fingerprint requirement was necessary to protect children, an assertion disputed by many advocates for migrant children. They point out that the Trump administration waived an FBI fingerprint check for workers caring for children in Tornillo.

Many potential sponsors are in the country illegally or have household members who are. That doesn’t disqualify them from serving as sponsors. But the new fingerprint requirements made many reluctant to offer sponsorship, critics of the new policy have said, causing children to languish in government custody for months. A report on Monday showed that ICE had arrested 170 people who stepped forward to sponsor a child, including more than 100 who had no criminal record other than an immigration violation.

15,000 children in government custody

Merkley, the Oregon senator, said Saturday that Dinnin told the delegation that many children continue to be inexplicably detained even after sponsors have submitted their fingerprints and other background checks. “Many of these kids have a sponsor who has already gone through the background checks. Thirteen hundred. And for some reason in the bureaucracy of the Trump administration, they are slow-walking completing that work, leaving these kids stranded here. So that, he said could happen. Within five days, 1,300 kids could be placed with sponsors already identified and already checked out. It shows you the dark heart of the administration that they are in every possible way trying to keep kids locked up,” Merkley said.

About 2,700 of the 15,000 migrant children in government custody are currently housed in what is supposed to be a temporary tent facility at Tornillo. O’Rourke said Saturday that an unknown number of children have been housed there since the summer. Other migrant children are housed at permanent shelters across the country, or at another temporary shelter near Miami. The Tornillo facility was set up in June because the government ran out of beds in permanent shelters as it began separating children from their parents when apprehended at the border. Such children were classified as unaccompanied by the government, even though they were traveling with their parents. The administration began enforcing the fingerprint requirements for sponsors shortly after Tornillo opened.

The Trump administration ended the controversial family separation policy on June 20, six days after Tornillo opened, and few separated children were ever housed there. But the number of migrant children in government custody continued to grow because the average time for placement with a sponsor grew from about 30 days at the end of the Obama administration to 75 days currently, congressional officials have said. Tornillo originally opened with 400 beds in June, then expanded to 500 in August and to 3,800 in September. Children there range in age from 13 to 17; about 500 of the 2,700 children currently in Tornillo are girls, members of the congressional delegation said Saturday.

The Trump administration said the number of children in custody has increased because more unaccompanied children are crossing the border, a need for more rigorous checks of potential sponsors, and because officials had to focus efforts this summer on complying with a court order to reunify families separated at the border. Administration critics, however, said the fingerprint policy is the biggest factor. They note that the numbers of unaccompanied children apprehended at the border are below those from 2014 and 2016, the two previous major surges of families and children from Central America.

- More About:

- Donald Trump

- Beto O'Rourke