This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Have you ever bought or sold a house?

If so, the actual closing of the deal was probably one of the most intimidating experiences of your life. You I went to the offices of a title insurance company, an institution you’d barely known existed before. You were handed a sheet with a few very large numbers on it and a lot of smaller ones, and you had to come up with the money. Some of the numbers you wondered about—why pay a “loan origination fee” for the privilege of borrowing money at an interest rate you ought to be paid to accept?—but they were like tollbooths, the only things standing between you and the deal, and so you paid. If you looked over the closing statement at all, you probably saw only one item where you thought you were getting your money’s worth, and that was title insurance.

I have some bad news for you. The catastrophes that it protects you against almost never happen. It’s a good thing, too, because your title policy would pay only a fraction of your actual damages. In addition, title insurance costs too much, due to a state regulatory system that rewards profligacy with higher rates. But you can’t decide not to buy it, unless you pay cash for your house: no title insurance, no loan.

I do not mean to suggest that title companies don’t perform a service and perform it well. But the people who are served are not the people who are buying the policies but rather the real estate professionals—brokers, lenders, and lawyers. That’s why the system is going to be hard to change.

“In 1979 Texas title companies took in $186 million in premiums and paid out only $2.9 million in losses. When you buy title insurance, you are really paying the company to protect you against its own mistakes.”

Late in the fall of 1969, Charles C. Stone, Jr., of Corpus Christi spotted some undeveloped land for sale near IH 37 west of town and decided it was the right place for the mobile home park he wanted to build. After more than a year of negotiations, he bought a little over eighteen and a half acres for $55,917. He arranged for a $370,000 interim construction loan and also got a commitment from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to insure the same amount for permanent financing. All the signs were favorable. The farthest thing from Stone’s mind was spending the next ten years and tens of thousands of dollars trying to rescue the venture, and himself, from financial calamity.

True, there had been one small problem. When he had first looked at the land with the seller’s real estate agent, Stone had been concerned about possible underground pipelines; he couldn’t very well build a mobile home park on top of a high-pressure gas line, and even if he were inclined to, he knew that federal regulations would force HUD to rescind its loan agreement. The realtor assured Stone that “pipeline alley,” where all the easements were located, lay outside the tract he was interested in, and so Stone decided to buy the land.

But the problem wouldn’t go away. Just as he was about to close the deal, he got a call from Eli Lipner, president of the agency that was writing title insurance for the transaction. Lipner wanted to know if Stone had heard anything about pipeline easements on the property.

“My Lord, Eli,” Stone remembers saying. “I don’t know of anything out there. That’s your job. You’re supposed to be the one that’s being paid to search the title.”

Lipner’s research staff had found that the pipelines were indeed on the property Stone wanted to buy, but the realtor, a close friend of Lipner’s, kept insisting that they weren’t. Eventually Lipner decided to take his friend’s word for it. He issued a policy that guaranteed Stone’s title, and in March 1971 the deal went through. Then, two months later, disaster: with the park 80 per cent complete, a high-pressure pipeline was discovered four feet within the boundary of Stone’s property. And it turned out that there were others; sure enough, pipeline alley was inside, not outside, the tract. Stone had to redesign his entire project, rerouting utility lines and moving fences, and he ended up with 21 fewer spaces than he had originally planned. This caused HUD to reduce its loan pledge substantially, and Stone, with his bank note coming due, was left short of permanent financing.

None of this was good news, but Stone wasn’t too worried. After all, he had title insurance. The title underwriting company had guaranteed that he owned his land free and clear; it had made a mistake, and now it would have to pay—for the diminished value of his land, for the loss of income from the smaller mobile home park, for the cost of redesigning it and the lost loan commitment, and even, Stone hoped, for the legal fees he was certain to incur.

The title company had to pay, all right—but only $2879. That didn’t even cover his legal fees, much less the rest of his losses. The case went to court, and Stone lost; he appealed all the way to the Texas Supreme Court; he sued Lipner for fraud; he burst into the annual rate hearing of the State Board of Insurance and poured out his story, telling how he’d contemplated “suicide or worse”; and just this year he tried to get the board to revoke Lipner’s license to act as an agent. He won a legal point here and there and, after eight years in court, a small amount of money, but nothing approaching his actual losses.

Charles Stone had the misfortune to find out what most people who have title insurance are lucky enough never to learn: if something goes wrong, it doesn’t offer much of a safety net. Stone’s title was insured, as is standard, for the amount he paid for the property. The easements represented about 5.15 per cent of the land. And 5.15 per cent of $55,917 is $2879. That’s the law. So sorry.

The basic problem is that title to land is merely a concept, rather than a legal document like title to your car. It is the magic combination of all the elements that constitute ownership. Suppose, say, you bought your house from Jones, who bought it from Smith, who had just escaped from a mental hospital. Jones’s title was no good because the law doesn’t recognize the conveyances of the insane. And so your title is no better than Jones’s—in other words, no good at all. If Smith’s son shows up tomorrow and wants the family house back, you’d better start packing.

This is the type of defect title insurance is designed to guard against. The Handbook of Insurance lists seventeen types of title defects that would escape notice in the course of a normal search of records, but in reality most of them are pretty unlikely today. Here’s just how unlikely these failures are: in 1979 title companies in Texas took in $186 million in premiums and paid out only $2.9 million in losses. Most of the losses were small amounts, and many of those were the results of poor research by the title company. On the typical sale of property, if the title company does its work properly, its chances of suffering a loss are zero. In other words, when you buy title insurance, what you are really doing is paying the title company to protect you against its own mistakes.

A century ago property often changed hands in unsophisticated transactions that didn’t go through batteries of closers and lenders and lawyers. Record keeping was not the best, either, and on occasion the state sold land that had previously been granted to someone else by Mexican authorities. (It was one such sale that led to the most famous of all Texas title disputes. Two sisters from Galveston showed up in Austin in 1925 with an ironclad claim to the land on which the Capitol is built. Back in the 1880s, when the state was acquiring the property, it had neglected to follow through on a notice of foreclosure sent to the sisters, and there was nothing the Legislature could do except pay up, $20,000 to each.)

Title defects still pop up occasionally, of course. Recall the constitutional amendment election last November that allowed the state to correct an error that threatened to dispossess a handful of East Texas farmers of land that their families had occupied for generations. But as a practical matter, the original purpose of title insurance—protection against the risk of undetected title failure—is no longer necessary. The old defects have been buried for decades, along with the people who could have taken advantage of them.

The kind of protection an owner really needs today, as Charles Stone learned, is precisely what title insurance does not offer. It provides no assurance that a buyer will be able to use the land as he planned to—Stone surely would not have bought the land had the title company informed him of the pipeline easement. It won’t protect him against claims by squatters, or zoning changes, or an Indian mound that state authorities want left undisturbed. Nor does title insurance take inflation into account: if your house is worth $150,000 now but cost you only $50,000, you’d better hope that the title company didn’t make a mistake, because it pays up on the basis of original cost. In short, title insurance doesn’t really benefit the buyer at all. But, as we shall see, it’s not designed to.

Title insurance is only the latest attempt to solve one of man’s oldest legal problems: establishing ownership of land. The intrinsic value of real estate—its fixed and permanent character—is also the source of all the trouble. Because no one can carry it off or destroy it by wrapping it around a telephone pole, it is attractive to people besides the owner. Creditors want it as security for a loan; governments want to put a lien on it if you don’t pay your taxes; pipeline operators want to buy a right-of-way for eternity.

By the nineteenth century, land registration laws required anyone wishing to protect an interest in land, whether a deed or a mortgage or just an easement, to file it in public records. As recording became routine, the standard practice was for the seller to furnish the buyer with a synopsis, or abstract, of all the documents relating to the title he had inherited from prior owners. The buyer hired a lawyer to examine the abstract and the seller’s own tenure, and if all was in order, the lawyer wrote a formal opinion saying so.

But suppose the lawyer made a mistake. Who suffered the consequences—the lawyer or the client? In 1868 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that attorneys could be sued for erroneous title opinions only if they had been negligent—something that is almost impossible to prove. And if, say, an easement had been improperly indexed in the public records, or if the title failed because of some defect not evident in the records, the lawyer couldn’t be held responsible, period. Soon afterward, the Pennsylvania General Assembly authorized the formation of title insurance companies.

The legal profession, as might be expected, did not surrender its involvement in real estate transfers without a fight. Lawyers helped develop the first abstract companies to reindex the poorly organized public records, thereby converting title searches into a volume operation conducted by nonlawyer employees. The title companies did likewise. The lawyers accused the title companies of unauthorized practice of law. The title companies fought back and won the right to do everything lawyers do except prepare the actual documents transferring property, such as deeds and mortgages. As recently as twenty years ago, most residential property in Texas still changed hands through a lawyer’s title examination. But in the end it was the lenders who finally tilted the outcome toward the title companies.

Until the sixties, most savings and loan institutions kept their outstanding mortgages in their own loan portfolios. They were willing to lend money on the strength of a lawyer’s title opinion because the officer who approved the loan usually knew and trusted the work of the lawyer who had researched the title. But in the last twenty years or so, the big financial institutions—insurance companies, pension funds, and bank trust departments—have been purchasing local mortgages in a big way. The national institutions operating in this secondary mortgage market don’t know one local lawyer from the other. They want their investments backed by title insurance and title insurance only, and the same goes for the Federal National Mortgage Association, which also buys mortgages. Since the local savings and loan wants to resell its mortgages, it, too, will accept only title insurance. And why not? After all, it’s the rest of us who have to pay for it.

The State Board of Insurance is one of the more prominent state agencies these days. If the board raises automobile insurance rates, it is front-page news in every major daily in Texas. If the board decides that the industry profit margin on fire insurance ought to go up, that too is widely publicized. Yet when the board did both for the title insurance industry in 1981, nobody noticed.

The annual title insurance rate hearing last November was mostly a family affair. The State Bar sent a representative; so did Dallas developer Trammell Crow and one other builder. I sat in the back of the small hearing room with two observers from the agency. The other 107 seats were filled with title insurance agents and underwriters. At the head table, the three board members sat facing the audience, flanked by two employees on one side and four industry lobbyists on the other. The atmosphere was relaxed and amicable, as it figured to be since both the insurance board staff and the industry were recommending an 8.4 per cent rate increase.

Nevertheless, the industry went through the motions of proving its case. It brought in a consultant from Boston who explained that (1) the title insurance industry is a stepchild of the real estate industry—nobody buys title insurance without buying property first—and (2) this has been a terrible year for the real estate industry. It seemed elementary logic that (3) this must have been a terrible year for the title industry too. The staff had compiled pages of figures inside a pink cover that explained how independent agents were making only a little better than 5 per cent profit and the underwriting companies were down around 1 per cent. Another witness reminded everyone that folks could make 17 per cent in the money markets these days; a 5 per cent profit just wouldn’t do at all. No one said anything to the contrary, and by midmorning the rate portion of the hearing was over.

One of the things that went unmentioned was a figure inside the pink cover. That figure was $309,160, and it was the total amount of losses independent agents suffered on title policies last year. That compared with $105 million in premium income. If this was a bad year, I wondered, what constitutes a good year?

In time I learned that title insurance is different from other types of insurance: it tries to eliminate losses through research, not make allowances for them. The main cost by far is the salary expense of paying people to copy courthouse registers, transfer the information to title company records, and then research those files over and over again. So the ratio of losses to income is not a valid standard of how the industry is doing. Unfortunately for the paying public, neither is the method used by the State Board of Insurance.

The board’s handling of title insurance rates is a case study in what’s wrong with letting government set prices. Regulation protects inefficient companies and keeps them in business. It is based on numbers generated by computers rather than on what is happening out in the real world. And it protects special interests—in this case, lawyers—who, if not placated, might raise a stink about the system.

Here’s how it works. Every title company in the state—big underwriters like Stewart Title, their wholly owned local agencies, and local independent agents—reports to the board all income and expenses. Actuaries plug this information into a formula and try to predict what rates will be necessary to give the industry as a whole a 10 per cent profit margin (the allowable cushion before 1981 was 7.5 per cent). The rates, based on the cost of the transaction, are much harder on commercial property than residential; a policy on a $100,000 house costs $650 and one on a $10 million office building costs $41,339. The rates are the same everywhere in Texas.

But the economy isn’t the same everywhere in Texas. Any Dallas title agency that was even close to the statewide average profit of 5.52 per cent in 1980 had a bad year; nine of the area’s fourteen independent agencies reported profits of 12 per cent or more. Yet Dallas buyers of title policies will get none of the benefit of this activity. They will be socked with the same increase everyone else in the state has to pay. In automobile insurance, the board varies the rate by county; why not for title insurance?

But that’s only the beginning. Because the rate-setting process guarantees that the industry’s sins will be forgiven in the next annual review, there tend to be a lot of sins. The worst of these is mandated by state law: every local title agency must have a complete set of records detailing every real estate transaction in the county for at least the last 25 years. In practice, most title plants, as these document collections are known, date back to the early part of the century in order to pick up the first pipeline easements. The expense of setting up a title plant is enormous—estimated at $2 million in Dallas—and the cost of keeping one up-to-date is no small matter either. Even in a slow year for real estate, US Life Title Company of San Antonio has nine and sometimes ten people at the Bexar County Courthouse every day taking down information from new filings of deeds, mortgages, divorces, and other records. Meanwhile, every other title company in town has its own people copying the same records. Statewide, almost half of all title agency expenditures goes for salaries, and much of that money is spent for this Dickensian copying and recopying that the public has to subsidize through higher rates.

A few title agencies have decided to pare expenses by consolidating their plants. But a different attempt to save money on plants boomeranged on policy buyers. Back in the late seventies, at the height of the real estate bonanza, there was a sharp upsurge in the number of title agencies in Houston. This growth was possible despite the steep cost of a new plant because a company bought an existing title plant and offered microfilms of its records, including weekly updates, for $250,000 to start, plus a graduated service charge. The new arrivals thought they’d found a money tree—that is, until the real estate bubble burst. Now there are too many companies for too little business, and while established independent agencies like Lawyers Title continue to do well (a 29 per cent profit in 1980), many of the newer entries, particularly those in the suburbs, are hurting. In a normal, unregulated competitive industry, marginal operators have to sell out or go out of business in hard times; in title insurance, their failure provides the seeds of their recovery, for it assures higher rates the next year. In effect, the insurance board’s rate structure practically guarantees them the right to stay in business.

Just as regulation saves the weak, it also encourages inefficiency. I am no statistician, but in looking over the 1980 reports from each of the 494 independent agencies, I could see that most of the urban money-losers (rural title companies, as we shall see, are altogether different) varied from the money-makers in ways that were evident from the tables. Successful companies spent only about 25 per cent more on salaries than on office administration, but many of the money-losers spent twice as much on salaries, or even more. They were reluctant to cut back in a year that called for retrenching. In short, they deserved to lose money: it was bad management, not bad times, that did them in. But the insurance board never questions expenses; it just adds them up, plugs them into the formula, and passes them on to consumers in the form of higher rates.

There’s one other reason for the ailing condition of the title industry that has nothing to do with the real estate slump: lawyers. In 1980 independent title agencies made $6.5 million in profits. They paid out $5 million to lawyers for closing services. Had they been able to avoid this expense, title agencies would have made the requisite profit last year and rates wouldn’t have needed to go up at all.

And the expense is totally avoidable. Most title agents handle closing—the transfer of money between buyer, seller, and lender—themselves, since closing services are included in the cost of title insurance. Some title companies, however, farm this job out to outside attorneys. Why? Because title companies have to rely on realtors or lawyers to bring them business (in most cases, neither the seller nor the buyer knows one company from the other). Those who prefer a sure thing have standing arrangements with attorneys: send your real estate clients to us and we’ll give you anywhere from 40 to 55 per cent of the premium for handling the closing. Of course, if the title company took care of the closing in-house, its actual cost would be a fraction of that. But it will pay what frequently amounts to a kickback (lawyers consider this a dirty word) in return for the referral. Lawyers consider that a dirty word too; they call the payment a fee for services rendered, but in the carefully chosen words of Robert Philo, who is in charge of regulating title companies at the State Board of Insurance, “In some cases the fees are justified. In some cases they are not.” Either way, into the formula they go and out come higher rates.

The closing game is particularly prevalent in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, where it wildly distorts the profitability of title agencies. Safeco Land Title in Dallas showed a $164,000 loss in 1980; it paid out more than twice as much in closing fees to lawyers. Southwest Land Title made a modest 2 per cent profit of $98,000 while rebating $381,000 to lawyers. But Plano Title, which handled its own closings and paid nothing to outside lawyers, chalked up a 17.4 per cent profit. A lot of title companies privately object to the huge rake-offs, but they aren’t about to stir up the legal profession, which can make life miserable for them in all sorts of ways, including accusations of unauthorized practice of law.

In rural areas, the adverse impact of lawyers on title rates is even more pronounced. In small towns the local title agency is frequently owned by a lawyer. Originally it was an abstract company and an adjunct of his law practice. But the insurance board allows the two to be treated separately.

I visited one such agency, owned by a friend and located in a small town in Central Texas. The entrance has two doorways, one for the law office and the other for the title company. Behind the two separate waiting rooms runs a single hallway leading to both offices.

The lawyer took me through the title plant, an area about the size of a large classroom. It was furnished with all varieties and vintages of filing cabinets, some big enough for bulky ledger books and others small enough for index cards. Employees bustled in and out of the room, always purposefully, and the atmosphere was not one of a business in financial jeopardy. I told him about the grim picture of the title industry that I’d gotten from the rate hearing.

“The real estate business stays pretty stable out here,” he said. “It’s great for us when things get volatile in the cities. That means our rates go up too.”

When I got home, I looked up his agency in the insurance board’s report. It was shown as a big money-loser. I called him back.

“Did you really lose money last year?”

“Huh?”

“The insurance board’s figures say you lost money last year.”

“The hell we did.”

I read him the figures. The hole in the agency’s pocket was an item called examination cost paid non-employees, which accounted for almost half of all expenses for the year.

“Oh,” he said, “that explains it.”

It seems that the title agency actually turns a tidy profit, but on its books (and when the numbers are reported to the state) the profit turns into a loss, for the firm’s bookkeeper shows it as a cost paid to the lawyer—its owner—for examining documents. “There must be a tax advantage to doing it that way,” my friend said. “All the companies around here do the same thing.” Texas title companies “spent” more than $9 million on examinations by nonemployees in 1980. If the state had counted this as profit rather than expense, the industry would have earned not 5 per cent but 12 per cent in 1980, and instead of a rate increase we could look forward to a rate reduction.

It is easy to see what’s wrong with title insurance; it is harder to know how to do something about it. For all the faults of the Texas regulatory system, it was twice described to me as the best in the country—by staff members at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and the American Land Title Association. What they actually mean, however, is that Texas regulates more than any other state, including rates and policy forms.

As for how Texas’ title insurance rates measure up against those in other states, comparisons are next to impossible. In Texas, closing services are included in the price of a title policy; in most other states, they are not. HUD recently published a study comparing title charges for a $50,000 house nationwide, and Texas did not come out very well: our charges totaled $495, higher than in all but nine states. But that total included $240 to lawyers for document preparation—deeds and mortgages—that is not part of the title premium. The charge is inexcusable (90 per cent of the time the documents were long ago copied right out of a book of legal forms and entered on a word processor), but it can’t be blamed on the title companies.

Obviously the State Board of Insurance could take steps to bring rates down. It could vary them according to local economic conditions. It ought to look for statistical ways to punish rather than reward inefficiency. It ought to encourage, if not require, consolidation of title plants to cut expenses. And it ought to throw its weight against the lawyers by forbidding extravagant rake-offs and kickbacks that have no relation to services performed. The board could even eliminate that noxious document preparation fee by allowing title companies to do the work at a fraction of what lawyers now charge.

The prospects for change? Poor. To its credit, the board has revised its formulas, over industry resistance, in the past few years to bring title company profits down a little. (Back in the early seventies, profits were around 20 per cent.) But the battles ahead are political, not arithmetical, and the board isn’t likely to ride to the rescue when no one is crying for help. The ordinary person doesn’t buy property often enough to stay mad; that’s the beauty of tollbooth economics. Realtors and lenders know what’s going on, but they aren’t about to complain, since someone investigating real estate transactions might decide to take a look at some of their tollbooths. Commercial developers, who have to pay the biggest premiums, don’t like the rate system, but in the end they can always pass the cost along.

Then why not deregulate the industry? The idea has occurred to, among others, William Daves, who is the chairman of the State Board of Insurance. Daves hinted that he favored deregulation in a 1980 speech to the Texas Land Title Association, but he told me that he has since changed his mind. The problem, as Daves and HUD and just about everyone else who has studied the industry have concluded, is that rate competition would not make title insurance more competitive, since the people who choose which title company to patronize are not the people who pay the freight but rather the real estate broker, the lender, and the lawyer.

When I bought my house, the realtor handed me a standard printed contract that read: “Seller at Seller’s expense shall furnish Owner’s policy of Title Insurance issued by [and here the rest had been typed in by the realtor] company of Seller’s choice.” Seller didn’t care, as is usually the case, so the realtor ended up choosing the company. I was told where to show up for closing, what time to get there, and how much money to bring. Until I started work on this story, I couldn’t have told you for a million dollars what company had insured the title to the most important investment I’ve ever made. Nor is this unusual: Ira Goodrich told me that he didn’t even know where to find his policy, much less who issued it, and Goodrich was for eleven years the title insurance industry regulator for the State Board of Insurance.

Advocates of deregulation argue that in a competitive marketplace, title companies would advertise lower rates to lure the public, but in most transactions, as in mine, the public never has a choice. The buyer doesn’t pay directly (though presumably the cost of title insurance, like the broker’s commission, is included in the asking price of the property), and the seller puts everything in the hands of the realtor. So title companies would continue to advertise as they do now: campaigns aimed exclusively at the permanent real estate industry—realtors, lawyers, and lenders.

It is next to impossible to attend a convention of one of these groups without eating title company food. Industry publications are replete with title company ads. Realtors’ desks are covered by title company maps and calendars. Most of the advertising is done by the large underwriting companies, and some is directed at independent title agents, who have a choice about where to place a policy. Stewart Title recently invited hundreds of independent agents to Galveston for a long weekend, put them up in the grandiose Galvez hotel, and wined and dined them at exclusive private clubs. On the local level, realtors choose title companies on the basis of which ones can close a deal quickly and smoothly—thus securing their commissions—and even in states where there is rate competition, referrals are still far and away the primary source of business for title companies.

But the biggest pitfall of deregulation is that it would promote the rise of title companies controlled by lenders, brokers, and builders. If you wanted the loan, or the property, you would have to use the in-house title company. With an assured flow of business, companies would have no incentive to keep rates competitive. One large California brokerage firm set up its own closing company and charged 50 per cent more than competitors without hurting its sales in the least. This is a nationwide trend that led to congressional hearings this fall, and there is no reason to think that Texas would be immune.

There’s really only one way out of the title insurance dilemma, and that is to simplify the land registration system on which it is based. It ought to be possible to transfer title to land the way we transfer title to automobiles. The most notable attempt at reform was made by Robert Torrens, a nineteenth-century Australian customs commissioner who later became a registrar of deeds. As a customs official he had registered ships simply by issuing a certificate to the owner with his name, a description of his vessel, and the names of all lienholders. When the ship was sold, the seller brought in his old certificate and the buyer got a new one. To prevent forgery, a copy was filed in the customs records. No doubt appalled by the unwieldy alphabetical indexes for land records, Torrens proposed a similar system for registering land by location.

Despite occasional successes—a few American counties, including Cook County, Illinois (Chicago), allow the Torrens system to coexist with traditional records—this approach has never gained much acceptance in this country, mainly because the owner has to go to court at his own expense to enroll his land in the system. In Virginia, for example, where the Torrens system has been authorized since 1916, not one piece of property has ever been registered under it.

But it isn’t necessary to ask the landowner to shoulder the cost of a Torrens system. In fact, the framework for the system exists right now in most of the large cities in Texas, stored in the computers of local title companies. The solution is simple, effective, workable, and cheap. Instead of 35 or so separate title plants in Houston, there ought to be just one—at the county courthouse. The title companies could hook their computer terminals into it for free, in exchange for turning over the information. A seller ought to be able to walk in, request the latest title information on his property, stand by while the clerk punches a button, and then take the printout to the savings and loan. The savings and loan could look it over, and if they were satisfied, the deal would go through.

And if they weren’t, they could always buy title insurance.

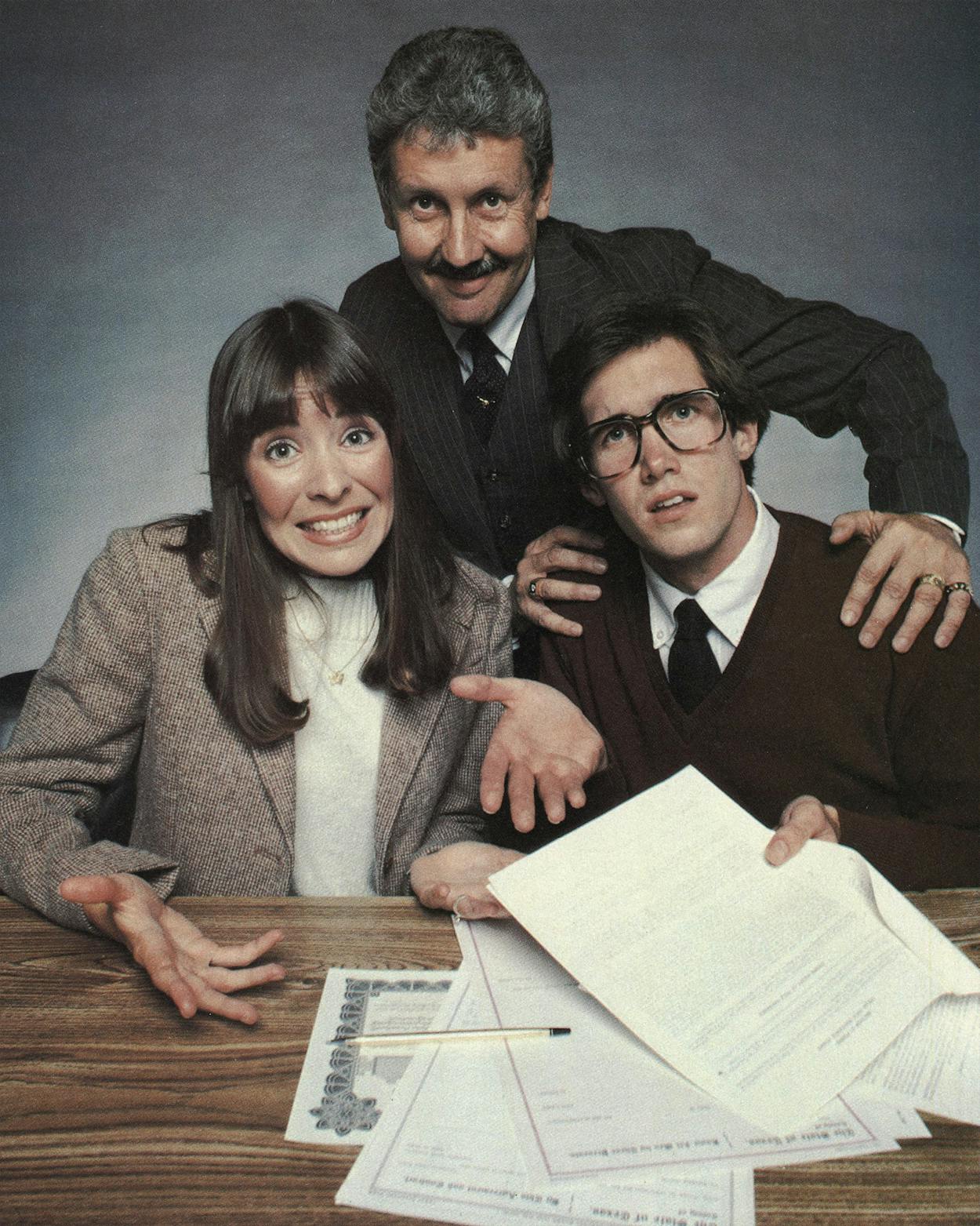

The Feast

When the real estate pros invite you to the closing table, they know they’ll be dining out—and the main course is you.

The Lawyer

He wants title insurance so he can get a kickback. And he wants your fee too.

The Lender

He wants title insurance so he can resell your mortgage. And he wants you to pay for it.

The Buyers

They don’t want or need title insurance. But they have to have it if they want a house.

The Title Agent

He wants title insurance so he can feed his kids. And at his prices, they eat well.

The Realtor

He wants title insurance so he can close the deal fast. And he wants his friends to do it.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads