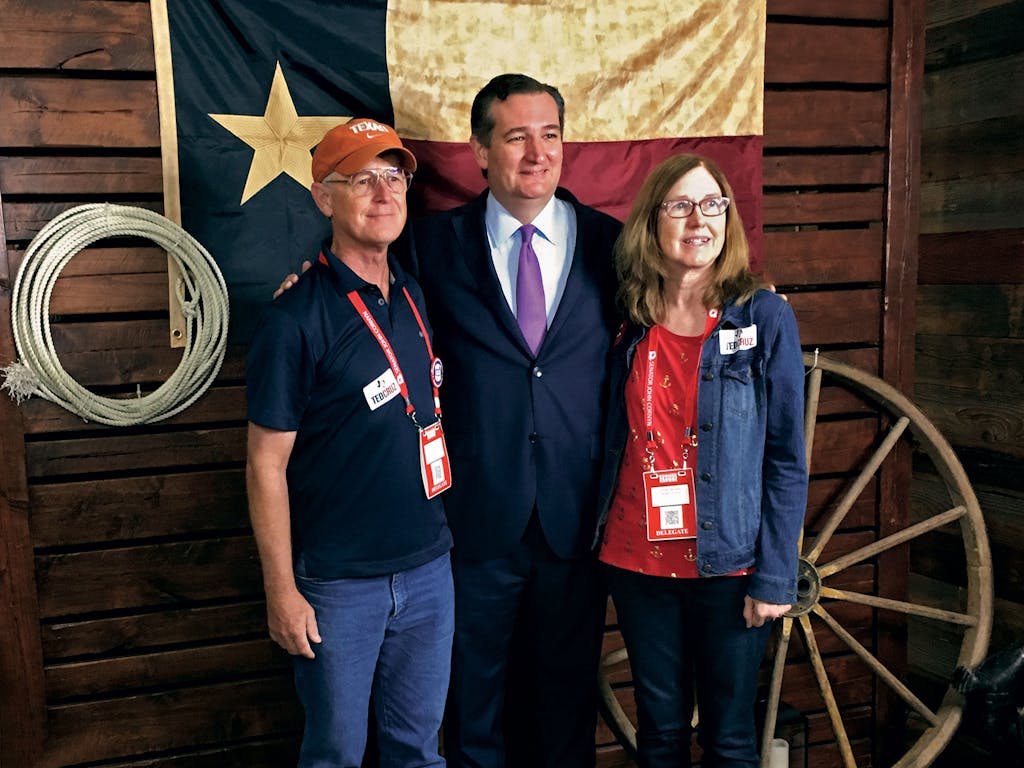

The line of delegates waiting for a photo with Ted Cruz was so long it seemed as if everyone at the Republican state convention, in San Antonio, was hoping for a bit of selfie stardom. The state’s junior senator stood in front of a barnlike wooden wall that featured a stonewashed Texas flag, a lariat, and a wagon wheel. Cruz wore black ostrich cowboy boots, a dark blue suit, and a purple tie—an unintended omen that underscored his opponent’s hopes that this year’s election may not be as “Republican red” as in the past. As thirty minutes turned into an hour, Cruz’s pollster, Chris Wilson, told me that he had begun to worry about the candidate’s feet swelling ahead of a charity one-on-one basketball game against TV host Jimmy Kimmel scheduled for that evening. (Cruz won.) The line kept coming, as did the compliments on Cruz’s service as senator.

Before the photo op, in a speech to nearly 10,000 of the party faithful, Cruz had extolled the virtues of tax cuts, conservative judicial appointments, and economic growth—all the while pledging his support for former rival Donald Trump.

“This election is a battle for the direction of this country,” Cruz declared. If the Democrats win Congress, he warned, and if his opponent, El Paso congressman Beto O’Rourke, wins in November, the end result will be Trump’s impeachment. Cruz sounded an unusual air of concern about O’Rourke’s prospects. “He is raising more money than any Democrat in the entire country,” said Cruz, referring to the fact that O’Rourke had raised $6.7 million during the first quarter (more than twice as much as Cruz’s campaign). “The hard left is angry. They’re energized.”

But now his speech was over, and as his fans gathered for a photo with him in the portable studio, Cruz’s smile looked genuine. State senator Konni Burton, a Colleyville Republican, cut in to the photo line while live-streaming to Facebook and asked Cruz if he had a message for Republicans. “November is about one thing,” Cruz said, looking directly into the camera. “Turnout, turnout, turnout.”

His off-the-cuff statement may be the rallying cry for 2018: getting voters to the polls will be the key challenge for both political parties in a state that has an abysmal record for turnout in midterm elections. Since 1998, no more than 40 percent of all registered voters have cast a ballot during midterm elections. That means the party that does the best job of whipping up its base will win. And no race on the November ballot is more likely to drive voter turnout than the battle for Cruz’s Senate seat; it has become the ultimate proxy war in Texas over President Trump’s performance in office.

For almost a quarter century, voter turnout in all Texas elections has favored Republicans. But this year Trump has created an unsettled political atmosphere with his combative tweets, ever-shifting policies on trade, aggressive tax cuts, and, most recently, a family-separation policy that has horrified even members of his own party. O’Rourke sees opportunity in this turmoil and is seeking votes not only from Democrats who cast a ballot in 2016 but also from disaffected Republicans and independents.

While O’Rourke and Cruz will critique each other’s personalities and pick apart each other’s policies, the contest is as much a referendum on Trump’s leadership as the 2010 midterm was a referendum on Barack Obama. In that election, Texas Democrats lost 25 seats in the state House, and 121 Democratic county commissioners and judges were swept out of office.

I have attended more than half of the state party conventions since the eighties and have witnessed the drama of Republican ascendancy in 1994 as well as a Democratic party verging on extinction in 2000. Most party conventions are big, expensive pep rallies. What set this year’s conventions apart was that no matter who was speaking at either gathering, Trump was the focal point.

Republicans met at their convention in San Antonio as the news of Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy and the resulting family separations was giving rise to national outrage. The Republican officeholders at the Henry B. González Convention Center ignored the topic. (The GOP convention ended before Trump reversed his family separation policy and signed an executive order banning the practice.) But their praise of Trump was effusive. Senator John Cornyn, for example, showed a music video set to the melody of the 1961 Jimmy Dean song “Big Bad John” with these rejiggered lyrics: “They think so alike, seem joined at the hip / One thing’s for certain, give neither no lip / Big Don. Big John.”

At the Democratic convention, held a week later at the Fort Worth Convention Center, Trump’s immigration policies were the focus. The Republican gathering hadn’t been completely devoid of passion, but I could feel elevated excitement from the moment I walked into the Democratic event —much like what you’d feel walking into a football stadium before a big game.

In order for a Democrat to win a statewide election for the first time in a generation, strategists must plot a course that provokes Democrats to turn out in numbers seen during presidential election years—and holds Republican turnout to its typical midterm numbers. That may be a tall order for even a charismatic candidate like O’Rourke, but Democrats believe that there’s hope that his charisma, in tandem with genuine anger at Trump, may do the trick.

Recent history should not be encouraging for them. Wendy Davis began her 2014 gubernatorial bid buoyed by hopes that her successful 2013 filibuster against anti-abortion laws would inspire pro-choice voters to turn out. But Davis’s campaign ultimately crumbled, garnering 270,000 fewer votes than former Houston mayor Bill White did when he ran for governor as a Democrat in 2010.

Democrats were likewise disappointed that voter turnout in this year’s Democratic primary was much lower than the Republican turnout. About 1 million Texas Democrats cast a ballot in March, while 1.5 million Republicans did. But there’s a silver lining for the Democrats: Republican data consultant Derek Ryan found that 27 percent of people who voted in the Democratic primary had not voted in the midterm primaries of 2010 or 2014; that was true of only 14 percent of voters on the GOP side. That suggests that there are a lot of Democrats who usually don’t turn out for midterm elections who might be inspired by their anger at Trump to show up at the voting booth in November. If O’Rourke can grab a big chunk of the 2 million voters who pulled the lever for Hillary Clinton in 2016 but didn’t bother to vote for Wendy Davis—and if he can stop Cruz from similarly inspiring his base—the much discussed, though never seen, Texas blue wave may yet make landfall.

As a sitting senator, Cruz has the incumbent’s advantage in national television appearances; he’s also touring the state in his Texas Cruzer RV with volunteers he calls the Cruz Crew. Over the Fourth of July holiday, Cruz visited the reliable Republican enclaves of College Station, Waco, Texarkana, and Nacogdoches. By that time, O’Rourke had created a viable campaign by raising millions of dollars over the internet, live-streaming his events, and visiting all 254 of the state’s counties. Even in Republican strongholds like Plano and Flower Mound, O’Rourke drew hundreds. Crowds may not equate to votes, but enthusiasm can.

Beyond campaign stops, another measure of a candidate’s effectiveness can be seen at its party convention. June of even-numbered years is political convention month in Texas. These partisan affairs are not attended by your average voter. Party delegates are some of the most politically involved people in the state. They are the activists who will work phone banks, stuff envelopes, and knock on doors for candidates. Both on the right and the left, they are the fringe on the state’s political cloth—some are just fringier than others.

The Challenge

The last time a Democrat won statewide was 1994, when half of Texas’s registered voters cast ballots. Turnout has not exceeded 38 percent since.

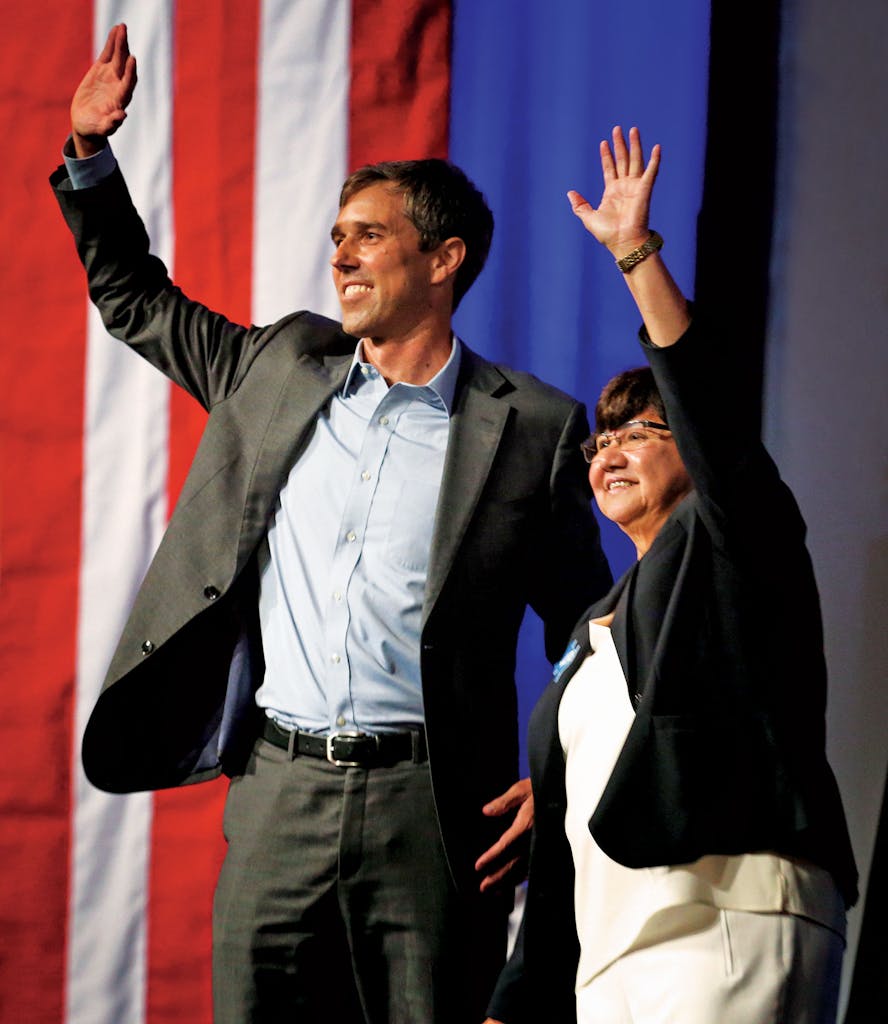

O’Rourke missed most of his party’s convention this year while waiting to vote on immigration reform in Washington. Yet even without his presence, delegates crowded his campaign booth at the convention hall, buying black T-shirts with the white “Beto” logo. When he finally appeared, O’Rourke was the undisputed star. After his convention speech, he held a rally at Shipping & Receiving, a bar with a large outdoor courtyard. More than 2,100 people signed in to see O’Rourke and waited for ninety minutes, sweating in the sultry 98-degree early-evening heat, for him to speak. The stage was decorated with a giant black-and-white portrait of him, with wooden cumulus clouds dangling from the rafters. One couldn’t help but think of the cliché about a liberal with his head in the clouds. Regardless, when O’Rourke stepped onstage and began speaking in his enthusiastic, stream-of-consciousness style, the audience was enraptured.

Never mentioning Trump by name, O’Rourke zeroed in on the president’s policies, especially the family separations, likening them to the time in 1939 when the United States turned away a passenger ship with almost nine hundred Jewish refugees aboard, forcing it to return to Europe, where more than two hundred of them died in the Holocaust. “Do you want walls?” O’Rourke asked. “No!” the crowd roared back. “Do you want the National Guard on the border?” “No!” “Do you want kids taken from their parents as a form of punishment?” “No!” O’Rourke called for universal health care and voiced his opposition to private school vouchers. The United States, he said, should be a land where you can “rock out in a punk rock band and tour the country and share your song.”

His message seemed to stir the audience. He also spoke about the need for increased voter turnout by those who are unhappy with the direction of the country. “We’re not going to get this done unless we answer to one another, that human-to-human connection,” O’Rourke said. “Folks, this is totally possible.”

Totally possible is a far cry from likely, let alone a done deal. What will it come down to? To quote O’Rourke’s opponent: turnout, turnout, turnout.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ted Cruz

- Donald Trump

- Beto O'Rourke