In mid-1975, just a few months after an engineer fresh from the University of Texas joined Exxon’s gas field operations near Katy, two of his supervisors discussed his performance. “I wouldn’t be surprised if he wasn’t a senior manager someday,” one said. After just a few months on the job, Rex Tillerson’s superiors could see his disposition was different than many other young recruits. “He was very even-keeled, level-headed and composed,” said the former supervisor, who like many former Exxon employees, asked that his name not be used. (The company frowns on even former employees talking to the press without permission.) “I never did see him get real emotional or upset.”

Tillerson, of course, outpaced those early predictions, ascending to the top of the country’s biggest oil company in his four decades with Exxon. Now, facing mandatory retirement in March, Tillerson is poised for a second act that’s as unbelievable as his supervisor’s prediction seemed back then: President-elect Donald Trump tapped Tillerson to oversee the nation’s global diplomatic corps as secretary of state.

While his Senate confirmation hearings—expected to start this week—are far from assured, Trump’s pick of Tillerson capped a two-week period late last year that turned a dour year for the state’s energy industry into a cause for celebration. First, OPEC announced production cuts that pushed oil prices over $50 a barrel. Then Trump, in addition to nominating Tillerson for one Cabinet post, chose former Governor Rick Perry for another: running the Department of Energy.

The appointments reinforced Trump’s promise to unshackle the industry by rescinding Obama-era regulations; working toward opening more federal lands to drilling; and defanging the Environmental Protection Agency. After eight years of the cold shoulder, the energy business is back in favor in Washington. “Energy got two early Christmas presents—OPEC and the appointments,” says Craig Pirrong, director of the University of Houston’s Global Energy Management Institute. “These appointments make it clear how dramatic the changes will be.”

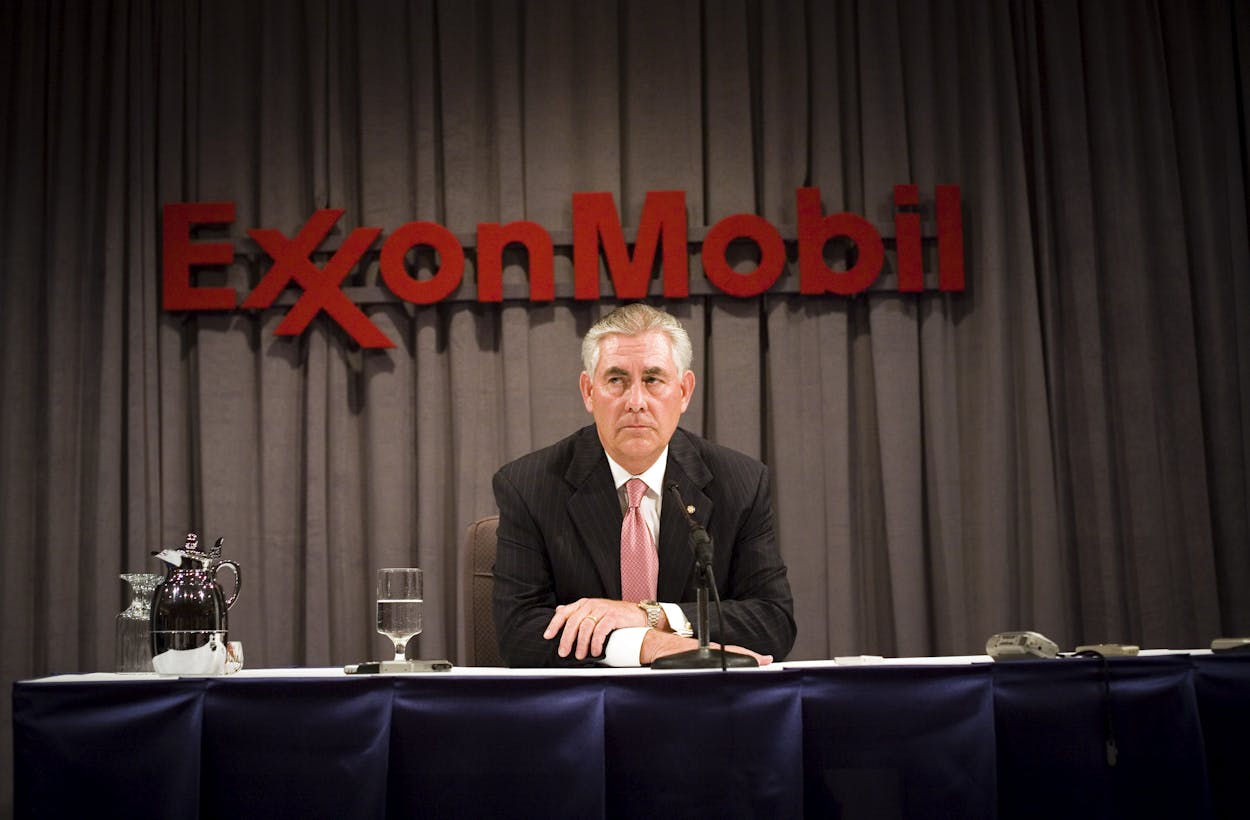

The OPEC decision matters more to most oil companies’ bottom lines because it essentially puts a floor on oil prices, but it was Tillerson’s nomination that got industry tongues wagging. The word most people use to describe the Exxon CEO, known for his silver mane of slicked-back hair and ample dark eyebrows, is “diplomatic.” Throughout his career he was known for treating colleagues with respect, for listening to opposing views, and for convincing even his staunchest opponents, often in countries such as Yemen and Russia, to understand his viewpoint.

“He had a reputation within Exxon as a smooth negotiator,” says a former Exxon executive. Trump, of course, loves the art of the deal, and Tillerson’s crowning achievement was negotiating Exxon’s 1996 agreement to find oil around Sakhalin Island on the eastern coast of Russia. The first well was drilled in 2003, and the success of the project led to Tillerson’s selection as the successor to Lee Raymond, Exxon’s often abrasive and intimidating former chairman. “Rex is not like that,” the former Exxon supervisor in Katy said. “He treated people with respect.”

By 2011, BP, Shell and most other western companies that had come to post-Soviet Russia in hopes of tapping the country’s vast oil reserves, had been kicked out by Vladimir Putin. Exxon, however, remained, and inked another deal, this one worth as much as $500 billion, to explore for oil in the Russian Arctic. Tillerson struck the agreement with Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin, whom the Russian press referred to as “Darth Vader.” Putin himself came to watch the signing, then famously awarded Tillerson Russia’s Order of Friendship in 2013. The close relationship with Russia is likely to be center stage in at Tillerson’s confirmation hearings. “He’s shown he can negotiate with the Russians and come out with good deals, but he’s not a patsy for Russia,” says Pirrong, who also writes a blog on Russian politics.

The challenge for Tillerson is translating his skill at negotiating business deals, which tend to be more narrow in scope and focus on specifics such as generating a return for shareholders, into the broader foreign policy negotiations required for a secretary of state. For Exxon, he was trying to convince Putin that the company was a good partner based on its technical and financial capability. That’s different from deterring or containing Russian aggression toward neighboring countries, for example. “That challenge is very different from those involved in representing Exxon’s interests, even if when doing so Rex was talking to many of the same types of people,” the former Exxon executive says.

Tillerson was born in Wichita Falls, and grew up in the Boy Scouts. His parents met at a scout camp sing-along when his mother, Patty, came to visit her brother. His father, Bob, took a full-time job with the scouts after World War II. The family later moved to Stillwater, Oklahoma, and later Huntsville, Texas. Rex became an Eagle Scout at age 13, and a year later, got his first job as a busboy in the Oklahoma State student union. Two years later he worked his way up to janitor in one of the engineering buildings. “I swept floors, dumped trash, polished linoleum floors, and cleaned the bathrooms,” he recalled. “It helped reinforce the dignity and value of honest work. It also gave me my first exposure to engineers doing research and solving problems.”

He graduated from UT with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and spent several years at the Katy gas field after joining Exxon. It was a small operation for a company Exxon’s size, with probably no more than twenty engineers managing the production in the entire field. Some of the wells had pressure that was so low, the gas had to be coaxed from the ground with compressors. Tillerson’s job was to monitor the compression and ensure the wells maintained a steady level of production. After Katy, Tillerson moved on to postings that included East Texas, Yemen, and, of course, Russia—spending his entire 41-year career with the company, which is common among Exxon executives. Critics wonder if Tillerson, after being steeped in a culture as staid as Exxon’s for so long, can adapt to running a giant government bureaucracy.

Complicating the transition is the fact that Tillerson and Exxon haven’t always agreed with U.S. policy. He is on the record as opposing economic sanctions, for example, even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. He also favors free trade agreements, which his new boss decried as job killers during the campaign. And in 2011, he cut a deal to pump oil from the autonomous Kurdistan region of Iraq against the wishes of the Iraqi and in defiance of U.S. foreign policy. The move put Exxon’s financial interests ahead of America’s goal to ease ethnic tensions and stabilize Iraq.

Tillerson and Trump, however, are likely to see eye-to-eye on other issues, such as the Keystone XL Pipeline. Trump has vowed to undo the Obama State Department’s decision to block the line’s border crossing with Canada, and Tillerson, an avid free marketer, is likely to agree. In a 2015 speech, he touted the project for benefits that went far beyond oil. “Keystone XL would do more than deliver oil from Alberta and North Dakota’s Bakken Shale to refiners on the Gulf Coast,” he said. “It would improve U.S. competitiveness, increase North American energy security, and strengthen the relationship with one of our most important allies and trading partners.”

Tillerson may also influence the Trump administration’s approach to climate change. Under his leadership, Exxon moved from staunch denial of change to tacit admission, although the company currently is embroiled in controversy surrounding the suppression of internal studies in which Exxon scientists warned of global warming even as executives were denying it. While not a climate change denier, Tillerson remains a skeptic of costly regulations designed to address it. At an Exxon shareholder meeting in 2015, Tillerson responded to a question about climate change by saying that Exxon doesn’t want to waste time on reducing emissions when those efforts may not work or may be unnecessary if current climate models prove to be flawed.

“Mankind has this enormous capacity to deal with adversity,” he said. “Those solutions will present themselves as the realities become clear. I know that is a very unsatisfying answer for a lot of people, but it’s an answer that a scientist and an engineer would give you.”

And, perhaps, a secretary of state.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Energy

- Rex Tillerson