At the Texas Republican Convention in Houston this past summer, delegates booed U.S. senator John Cornyn. Congressman Dan Crenshaw was heckled by far-right activists as a “globalist RINO.” Governor Greg Abbott and Texas House Speaker Dade Phelan declined to address the convention, apparently fearing a similar reception. “The Republican Party of Texas is a grassroots party,” declared state party chair Matt Rinaldi in his opening remarks. “It doesn’t belong to me, or the governor, or senators, or congressmen, or any elected official.”

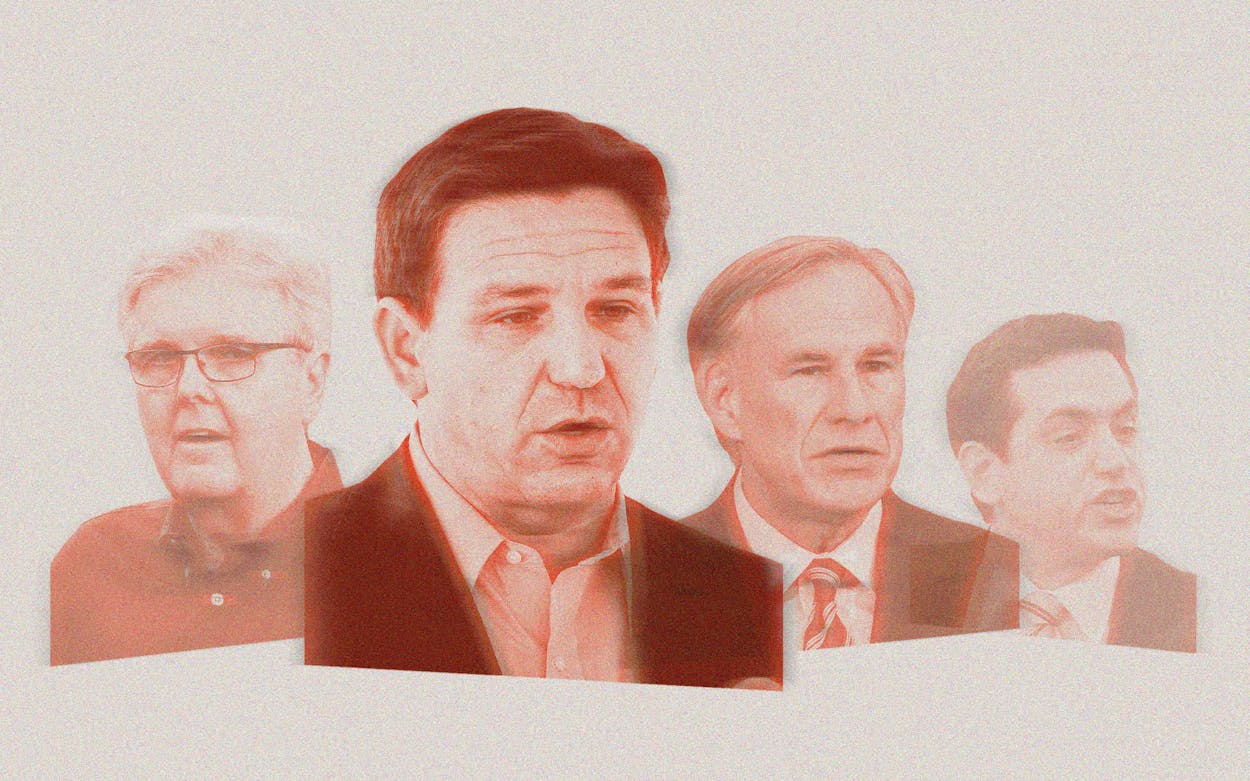

But there was one elected official whom Rinaldi, along with many of his fellow speakers, was eager to celebrate. “Ron DeSantis in Florida [has] stood up and gone on offense against corporations like Disney who receive special favors from the government while taking harmful positions on social issues,” Rinaldi told the crowd, to rapturous applause. Next to former president Donald Trump, no Republican received more praise from convention speakers than Florida’s firebrand governor, who became a right-wing folk hero during the pandemic for his opposition to vaccine and mask mandates.

DeSantis’s massive victory in November—when he crushed his Democratic opponent (a former governor) by more than nineteen points to win a second term—cemented his exalted status among Texas Republicans. With Trump’s handpicked candidates foundering from coast to coast, DeSantis’s triumph seemed to offer the GOP much-needed hope. The day after the election, Rinaldi tweeted, “Ron DeSantis and his optimistic brand of bold and unapologetic conservatism is a winning brand and the GOP should take note. . . . He led, rather than followed polls. He stood for something. He took risks. He rejected moderation. He inspired people.” State representative Briscoe Cain, a Republican from the Houston suburb of Deer Park, tweeted, “The DeSantis Wave is a mandate for Republicans to be bold in leadership and to fight for parental choice and educational freedom for all.”

Indeed, the eighty-eighth session of the Texas Legislature, which begins January 10, will be conducted on political terrain staked out by DeSantis. Lawmakers have already filed numerous bills that would constrain the government’s ability to fight pandemics and prevent private companies from imposing vaccine mandates—issues that have become identified with DeSantis. Bills have been introduced to increase public scrutiny over books purchased by public school libraries (similar to a Florida law passed in March) and criminalize gender-affirming medical care for children (which Florida banned in November). Yet another bill would establish a cadre of state “election marshals” to investigate voter fraud—an idea seemingly inspired by DeSantis’s Office of Election Crimes and Security, which has charged twenty Floridians with voting illegally since it was established earlier this year.

“Some of us at the Capitol have joked that we need to have Miami Herald subscriptions so that we can read today what Greg Abbott is going to do three days from now,” said Scott Braddock, editor of the Quorum Report, an influential newsletter about Texas politics. With Trump’s influence weakened by his loss in 2020 and his chosen candidates’ poor performance in 2022, the Republican base is increasingly turning to DeSantis as the party’s ideological lodestar. In the view of Rice University political scientist Mark Jones, DeSantis “provides the more conservative wing of the Republican Party with an example of what they believe Greg Abbott and other Republicans should be doing here. It’s pretty common to see Texas Republicans use things that DeSantis does as a way to prod Abbott and other Republicans to move in a similar direction.”

Rinaldi, the state Republican chair, declined an interview request for this story. His spokesperson issued a statement saying that “DeSantis has no influence on the Texas GOP other than inspiration for good GOP leadership.” But there’s no denying DeSantis’s popularity among Texas Republicans. A poll conducted after the November election by the state GOP found that 43 percent of the state’s likely Republican voters would support DeSantis in the 2024 presidential primary, with 32 percent backing Trump. (Oddly, the state GOP did not give voters the option to choose Abbott, Senator Ted Cruz, or any other Texan.) Without Trump in the race, fully two-thirds of Texas Republicans said they would support DeSantis.

To understand DeSantis’s popularity with the Republican grassroots, you have to go back to the beginning of the pandemic. For the first few weeks, the Florida governor followed federal guidance—ordering a state lockdown, sealing off nursing homes, and setting up hundreds of testing centers around the state. Unlike President Trump, DeSantis even wore a mask in public. But after consulting a group of heterodox health experts and “doing his own research,” DeSantis became convinced that these measures were, at best, counterproductive. He started lifting Florida’s lockdown in April 2020; in July, he ordered schools to reopen. By September he had removed almost all remaining pandemic restrictions and issued an executive order prohibiting local governments from enforcing mask mandates. In November 2021, state representative Tony Tinderholt, a Republican from Arlington, praised DeSantis as a leader of the resistance, tweeting that “Texas should be in a special session right now to stop the Biden left-wing mandates.”

Even as the bodies stacked up—an estimated 84,000 Floridians have now died from COVID-19, giving it the country’s fourteenth-highest per-capita death toll (Texas is thirty-third)—DeSantis stuck to his guns, refusing to take further preventative measures. After initially promoting COVID vaccines, he appointed a surgeon general, Dr. Joseph Ladapo, who downplayed their effectiveness. “There’s nothing special [about vaccines] compared to any other preventative measure,” Ladapo said.

While DeSantis won praise from right-wing media outlets for his early opposition to pandemic health measures, Texas’s governor was getting slammed for being too slow to lift restrictions. Like DeSantis, Abbott initially ordered a state lockdown. But he waited longer than his Florida counterpart to begin reopening the state, and in June 2020, following a spike in coronavirus cases, Abbott paused the state’s plan to fully reopen. He waited until March 2021—six months after DeSantis—to lift all COVID restrictions. Two months later, he finally issued an executive order banning local mask mandates.

An impression was solidifying among the Republican base that Abbott was merely following DeSantis’s lead when it came to the pandemic. While DeSantis cultivates the image of a fearless truth-teller, Abbott often comes across as a political weather vane. And at the moment, the wind is blowing from an easterly direction. “DeSantis is definitely more of a risk-taker,” Braddock said. “Because Florida is a more competitive state for Democrats, DeSantis’s investment in these right-wing populist policies was a bigger risk than what Abbott is doing in Texas.”

Before the pandemic, Abbott was often mentioned as a potential presidential candidate. But as DeSantis’s star has risen in the GOP firmament, Abbott’s has fallen. “If you look at speculative lists of presidential candidates, Abbott’s often not on them at all,” observed SMU political scientist Cal Jillson. “You can go ten candidates deep and his name isn’t there.”

Abbott’s dearth of political convictions and deeply cautious nature has created something of an ideological void at the top of the Texas Republican Party. Having already passed most of its highest-priority legislation, the party appears happy to let DeSantis set much of its legislative agenda. On issues ranging from “parental rights” to election law, Florida is leading and Texas is following. It’s a strange situation for a state that has sent three presidents to the White House and has grown accustomed to setting the national conservative agenda. “Texas and Florida are the two big Republican model states,” Jillson said. “They compete with each other to be the leading red state in the country.”

The influence doesn’t just run one way. In July, DeSantis signed a bill eliminating ballot drop boxes and making so-called ballot harvesting a felony—two laws that Texas had passed a year earlier. But anyone wondering which red state is leading the way just needs to look at the pre-filed bills for the upcoming session of the Texas Legislature, many of which appear to be inspired by legislation that has already been signed into law by DeSantis.

For years, Texas Republicans have warned that our beloved state is turning into California. All that time, it seems, they just wanted to turn it into Florida.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott

- Austin