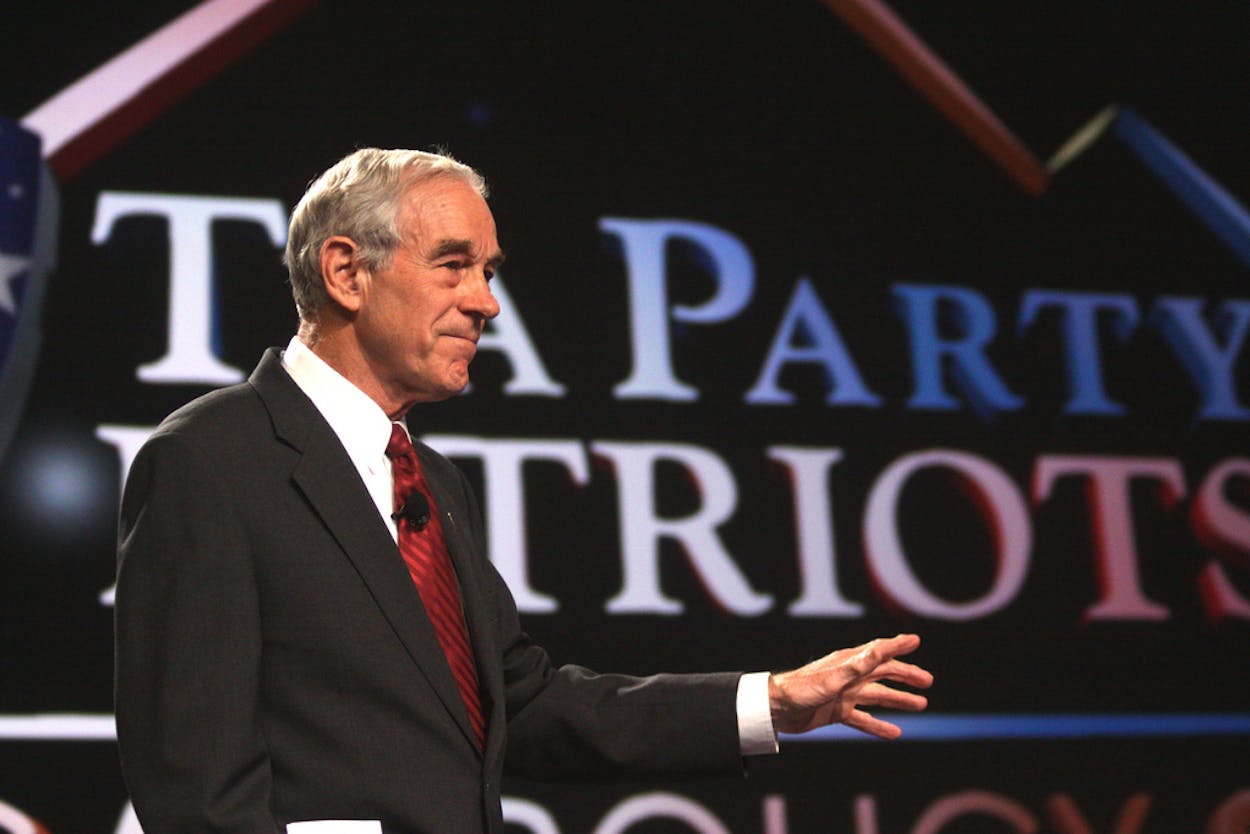

“How did libertarian Ron Paul become the 13th floor in a hotel?” Jon Stewart asked of the Republican presidential primary candidate last August, a quip that Kelefa Sanneh of the New Yorker cites early in a long profile of Paul that appears in the magazine’s February 27 issue. The timing of this piece speaks to that same notion–the New Yorker itself has published pieces on Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, and most recently, Newt and Callista Gingrich, before finally turning to Paul.

Sanneh himself knows that it’s a bit late in the game, observing, of Paul’s delegate strategy, that those delegates are only “worth something until the last night of the Republican Convention, at which point the market for Republican delegates crashes.” He also suggests that “there’s no telling whether [Paul will] even vote Republican in November.”

Sanneh didn’t get the kind of access that would really let a reader get to know Paul, even with reporting from Maine and Nevada. Most of the story unfolds from a distance at public appearances, except for one brief moment in the lobby of the Las Vegas Four Seasons, where Sanneh asked Paul about a former political enemy:

In the summer of 1981, Paul introduced a simple bill, with no co-sponsors: “A resolution that United States District Court Judge William Wayne Justice is impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors.” Justice had issued a series of rulings in the nineteen-seventies and eighties that led to the desegregation of Texas schools and, in response to claims of overcrowding and abuse, the reform of state prisons. The outcry made him perhaps the most hated man in East Texas. Local businesses refused to serve him, and his detractors printed up bumper stickers that anticipated Paul’s resolution, and may have inspired it. “Impeach William Wayne Justice,” they said. Paul’s resolution was purely symbolic—it never progressed beyond the House Judiciary Committee—and interest in the issue apparently faded. Now, perched on the couch, he was having a hard time remembering how, exactly, the Judge had come to seem like a grave threat to liberty.

“Yeah, I remember I was real energized back then,” he said, sounding puzzled. “I think it was the intrusion aspect. I’m not sure if I have the same opinions that I had—I can’t even tell you what he was intruding on. I think it was how to run prisons, or something?” Paul thought a moment. “He was probably demanding more protection for prisoners. Since I think we have too many nonviolent prisoners, I might have more sympathy for what he was saying, back then.” He chuckled.

Fortunately, TEXAS MONTHLY‘s Paul Burka still remembers, as Justice, of course, was a giant of our state (the University of Texas’s Center for Public Interest Law is named for him).

As Burka wrote when Justice died in 2009 (drawing largely on his 1978 profile of the judge), he was:

…the last, the most important, and the most influential of the Ralph Yarborough generation of liberal Democrats, unrivaled even by Yarborough himself. His rulings as a federal judge reached into just about every corner of state government. He reformed the prison system, integrated the public schools, redrew redistricting maps, told timber companies how to harvest their trees, and forbade school districts from charging tuition for the children of illegal aliens.

Nowhere did Judge Justice’s impact loom larger than at the state Capitol. The Ruiz case demanded reform of the state prison system, in which order was maintained by “building tenders” — essentially, a gang of inmates handpicked by prison administrators to maintain order through threats and assaults. The use of building tenders allowed the prison system to maintain a minimalist force of guards, with the result that Texas ran the lowest-cost prison system in the country. The Ruiz case put an end to the reign of terror. Judge Justice similarly demanded reform of the juvenile justice system. He mandated improvement of bilingual education programs in Texas schools. In the Ten Best and Ten Worst Legislators article of 1981, I wrote that Judge Justice “did more to shape the appropriations bill than any member of the budget committees; did more to shape legislative districts than any member of the redistricting committees;” and, I might have added, “did more to shape education than any member of the education committees.”

For all the criticism and grumbling from legislators that Judge Justice’s rulings and remedies generated over the years, there is no question that Texas is a better state for what he has wrought.

Should Ron Paul have a better memory of such a pivotal time in the social and politicial history of Texas, especially since many of those issues (and actual court cases) simmered for another twenty years?

Sanneh spoke to MSNBC about his story Monday morning:

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Ron Paul