The fire marshal must have been on vacation the day that Ann Richards dedicated the José Escondón Elementary School in the La Joya Independent School District. Every available square inch in the cafeteria was occupied. Schoolchildren on their best behavior sat cross-legged on the floor in front of a curtainless stage. Their families—not just parents and siblings but aunts and uncles and grandparents and cousins—sat in row after row of folding chairs, until the chairs ran out, and then they stood three-deep along the cinder block walls, and then they jammed into the open doorways and spilled out into the school yard, straining for a glimpse of the governor. Most of the men wore suits and ties; women were in dresses and heels. The Saturday afternoon ceremony in late February was a big occasion in this westernmost outpost of the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

It should have been a big occasion for Ann Richards as well. She has done more for South Texas than any other governor: lobbied for NAFTA, named a highway commissioner from this oft-neglected region, provided relief for residents of colonias that lacked running water, successfully advocated a plan to immunize children against disease. The mostly Hispanic crowd represented an important part of her political base: hardworking, struggling families who care about their kids and worry about the future. Here was a chance for Richards to generate momentum for the difficult election campaign that lay ahead.

But she didn’t take advantage of it. Right from the start, she seemed down in the dumps as she addressed state lawmakers in the audience: “As legislators, you start out full of ambition and hope to go to Austin and do what you want to do, only to have your hopes dashed because this is a democracy and someone else has a vote equal to yours.” Although the governor looked resplendent in a pink jacket and a black skirt, her performance was listless and utterly mystifying. Even the trademark silver hair looked less poufed than usual. She missed a chance to connect with the crowd when she said to Congressman Kika de la Garza, “I’m going to be up there soon and talk to those boys you work with, and those girls too, about the help we need with”—guess what? Not any of a dozen things the Valley desperately needs, from infrastructure improvements to environmental cleanups. No, it was—“that superconducting supercollider.” A dead project hundreds of miles away.

And so it went, one melancholy note after another. “If you see someone in law enforcement or education,” she said, “please thank them, because they will never get enough money to do what they need to do.” Instead of talking about all she had done for South Texas, she seemed almost apologetic when she told the schoolchildren, “Your parents pay taxes, and in this school district they pay very high taxes because of the way the school-finance formula works.”

Ann Richards’ popularity remains high. Her lead over George W. Bush holds steady in the polls. But inside, something has changed. She has lost the exuberance of her first months in office. During her speech, Richards made a modest promise or two, the audience clapped politely at several points, and a couple of jokes elicited light ripples of laughter. But she never really roused the crowd or herself. Who would have thought than Ann Richards, the first Texas governor to come up through the liberal wing of the Democratic party, would go to La Joya to deliver a speech that seemed to say, “Ask not what your government can do for you, because it can’t do very much”?

If the speech in La Joya had been an isolated incident, her mood could be explained by the cough that troubled her frequently during the speech or by the recent death of her father. But it was not just an isolated incident. A message of dismay with government has been popping up in Richards’ speeches and private conversations for more than a year. It has been so persistent that some of her close friends were not sure that she would run for reelection—or that she should. Last year, in a speech at the University of Texas introducing Hillary Rodham Clinton, Richards talked about how people expected too much from government. It was a strange prelude to the first lady’s pitch for a government program of universal health care. At a meeting of people Richards had just appointed to state boards and commissions, she told them how disenchanted she had been with some of her initial appointees. Near the end of the 1993 legislative session, I saw her in the halls of the Capitol and mentioned to her that she didn’t seem to be enjoying herself the way that she did during the 1991 session that followed her election. Her response was: “If you mean, ‘Am I sadder but wiser?’ the answer is yes.”

What happened between the time that she took office determined to change government and the time that she became disillusioned? By ordinary political standards, she has had the most successful tenure of any Texas governor since John Connally—a long list of legislative achievements, a revitalized state economy, national stardom, continuing popularity at home—and yet at times she seems to draw little solace from it. Ever the perfectionist, she is haunted by her failures rather than invigorated by her accomplishments. “She has that old Methodist social conscience,” says her former chief of staff, Mary Beth Rogers. “You think it’s your responsibility to do everything.” When Richards was state treasurer, she could easily fix the simple problems she came across. Now, as governor, she can’t. The problems aren’t so simple.

“Someone sent me a newspaper from Ma Ferguson’s time,” Richards told me during an interview in her office. “Do you know what the issues were? Schools, prisons, and insurance. It doesn’t change much, does it?”

But the difficulty of making government work might be only one explanation of why Richards has grown sadder but wiser. The other is that the people who have done her the most harm are not her enemies but her friends—in particular, her appointees and her staff. Lena Guerrero’s resignation from the Railroad Commission after she lied about her academic credentials was only the most public debacle. At least Guerrero understood politics. Richards has surrounded herself with too many people who don’t know how to operate as insiders. They don’t understand that a Texas governor, and all those who work for her, must compensate for a lack of constitutional power with political savvy and goodwill.

Politics is a cruel profession. It takes a special kind of person to undertake public service and remain undismayed. If only 40 percent of the people want to fire you, you win by a landslide. The public doesn’t understand the intractable nature of the problems, and if you try to educate them, they don’t want to hear. “I heard the speech,” a cynical journalist named Jack Burden tells Willie Stark, an earnest candidate for governor who tries to use facts and figures to persuade voters, in All the King’s Men, the greatest of American political novels. “But they don’t give a damn about that. Hell, make ‘em cry, or make ‘em laugh, make ‘em think you’re their weak and erring pal, or make ‘em think you’re God-Almighty . . . Tell ‘em anything. But for Sweet Jesus’ sake don’t try to improve their minds.”

In La Joya, Ann Richards made the mistake of trying to improve minds. She was trying to get a group of people whose needs are almost unimaginable to understand how little she can do for them. It is hardly surprising that this was not a welcome message. Richards’ political strength is her genuineness—her ability to transmit her real personality and real feelings to the public and to make the public care how she is doing. That is why she is one of the rare politicians—for a time, Henry Cisneros was another—who is embraced by her constituency on a first-name basis. She is, simply, Ann. But that very genuineness could be her undoing, if what she transmits is doubt about her own ability to make a difference. As Ann Richards nears her showdown with George W. Bush, the biggest obstacle to her reelection may be her own state of mind.

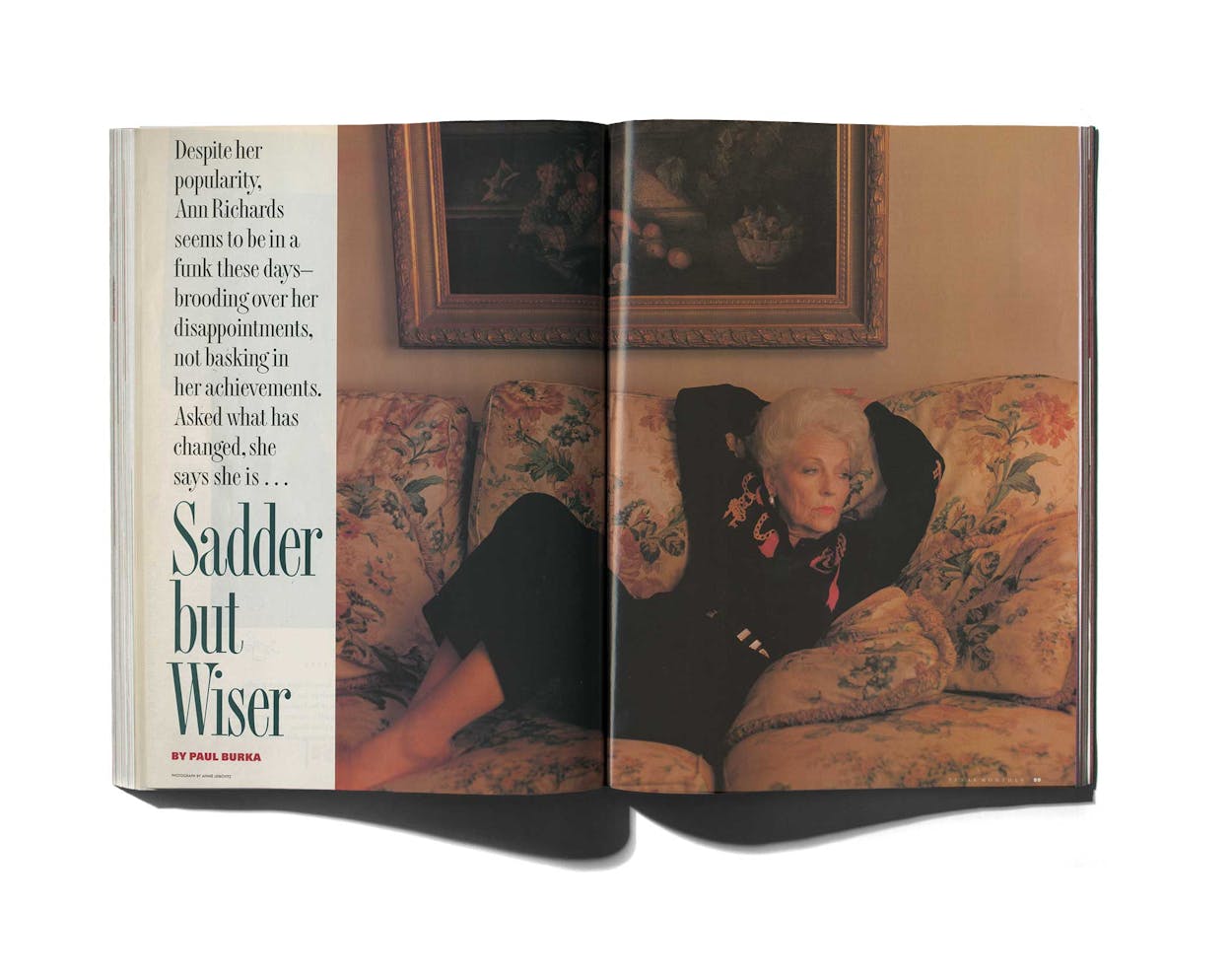

On Texas Independence Day, Ann Richards was receiving visitors in her living room, on the second floor of the Governor’s Mansion. The stairs from the back of the mansion led directly to the living room and passed under a large framed print of a quotation from Richard King, the founder of Texas’s most famous ranch. “People who come to Texas these days are preachers, or fugitives from justice, or sons of bitches,” it reads. “Which one of those fits you?”

Richards was wearing a navy suit with a lone star pin on the right lapel. She sat regally in a chair for an hour, never once uncrossing her legs or fiddling with her jewelry. Only her head and her hands moved. Her demeanor contrasted mightily with the action on a table behind her, where an Amazon green parrot stood on top of its open cage, chattering incessantly, ruffling its feathers, rearranging itself to hang upside down on the side of the cage, and pecking on the bars.

“That’s Gracie,” said Richards. “It’s short for Amazing Grace.” I told her that I had come to ask what she had meant a year earlier, when she said that she was sadder but wiser.

“I’m wiser because government is much harder to change than I thought. I’m sadder because politics is a lot meaner than I thought. It’s a game of ‘gotcha,’ and it’s played by everybody. ‘Gotcha’ if you try to do it right and ‘gotcha’ if you do it wrong. ‘Gotcha’ because people want instant gratification that is simply not going to occur. We take too much sport in other people’s discomfiture.”

Was she alluding to the Kay Bailey Hutchison case? I asked. Republicans had sought Richards’ records to prove that Democrats were just as guilty of ethical violations as Hutchison. Just before the trial, the news broke that Richards’ staffers had destroyed some phone records. The bizarre ending—Travis County district attorney Ronnie Earle abandoned his prosecution because he feared that the presiding judge would disallow his evidence—fed speculation that Richards might have called Earle off the case to protect herself.

“The minute I heard about Kay’s indictment, I said, ‘This is the worst thing for everybody,’” Richards said. “I knew how it was going to play out. We’re both women. We both held the same office [state treasurer]. I knew that her guys—and I don’t think it was Kay—were going to come after me.”

Everybody in Texas thinks you called Ronnie Earle, I said. Did you?

“Absolutely not. And, no, everybody doesn’t. I never talked to him about the case or anything else while it was going on. I like Ronnie, but we’re not close. I tried to cut his budget when I was county commissioner.”

I asked her about her mood: “Your speech in La Joya seemed very melancholy to me. Can you win reelection in your current state of mind?”

Richards arched her eyebrows in disapproval. “Oh, I think you’re being melodramatic,” she said. “The process is so difficult. But I don’t feel melancholy. That’s simply the way it is. That’s reality.” But there is another reality, and that is that the public wants a leader who believes that the process can work.

No one was describing Richards as melancholy after her first legislative session. Late in the summer of 1991, Richards was riding high. Her major legislative initiatives were all successes: the state lottery, a tough ethics law, insurance reform, and stronger environmental standards. She had embraced the idea of decentralized education in a new law giving principals and teachers more authority to manage their schools. Critics complained that she had showed insufficient leadership on big issues like school finance. Still, it had been a long time since Texas had had a governor who showed leadership on anything.

In fact, Richards never believed that the Legislature was the main battleground. The real fight was with the bureaucracy. She had run on a “New Texas” platform of breaking up the old-boy network that dominated state agencies. “Everything was too easy,” a Richards campaign adviser told me, looking back at the government Richards had inherited. “It was too easy to get a parole. It was too easy to get a permit to dump waste. You could build a highway without even thinking about the environmental consequences. Regents thought their job was to work for their university, not the public. That’s the way it was in every agency.”

The New Texas solution was to appoint more women and minorities who weren’t part of the old-boy network and to make the process more open to opponents of business-as-usual. But in Richards’ second year as governor, the idea began to lose momentum when Lena Guerrero, the showcase appointee of the New Texas, had to resign from the Railroad Commission in disgrace. That episode is the most prominent example of how Richards has been undermined by her own team, but there are many other cases. The story of three high-visibility state agencies, with responsibility for the environment, education, and insurance, indicates how she wanted government to work and why she grew disillusioned.

– Success Story: The Natural Resource Conservation Commission. John Hall, the chairman of the state’s main environmental agency, is the prototype for the New Texas—young (39), black, and politically astute; a mainstream environmentalist, not an ideologue. Under Hall, the commission has been tough on the politically unpopular waste disposal industry and reasonable toward the politically potent chemical industry. (It will allow chemical companies to come up with their own plans for reducing emissions instead of requiring that they submit to commission orders.) Hall is a skilled juggler of competing interests. Under pressure from environmentalists, the agency slowed down the process of granting permits sought by industry. Then, under pressure from industry, Hall agreed to speed up the process. Everybody likes him.

– Disappointment: The Texas Education Agency. The TEA is a terrible agency. Until last year, the bureaucrats had tenure. They remain resistant to education reforms and display special animosity toward the idea that schools should be accountable to the public. Almost four years ago the Legislature passed a law requiring school districts to issue report cards, so that parents would know how individual schools compared with others across the state. Parents have yet to see any meaningful report cards

Richards’ handpicked choice for commissioner of education, Lionel “Skip” Meno, was supposed to change all this. Meno brought with him from New York a reputation as a visionary who knows what works in education, and he has made some progress towards decentralization and a stronger curriculum. But he hasn’t been able to redirect the agency towards reform or ride herd on its entrenched bureaucracy. A former Richards staffer recalls that the governor was so unhappy with the TEA’s performance that whenever she saw Meno she would ask, “How many bureaucrats have you let loose?” One day, Meno told her proudly at a luncheon, “Governor, I let one go for you.”

Meno was supposed to have been Richards’ main line of defense to the charge that she hasn’t been a leader in education. Everybody from Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock to the Dallas Morning News criticized her for staying out of the school-finance fight after offering an early plan that the Legislature ignored. But there was little more than she could do. The issue was too infused with local politics—how various plans affected individual school districts—and the courts had left the Legislature no good solution. Instead, Richards put her chips on Meno and an overhaul of the TEA. But Meno hasn’t been able to reverse the trend of issuing more and more rules and measuring the effect of each one.

Richards’ discouragement with government was evident when she talked about Meno during our interview. “The enormity of what he was trying to do and the black cloud of the finance issue made it hard to move ahead,” she said. “It’s so hard to change anything even in the best of circumstances. If you try to eliminate bureaucrats, you get sued. If you try to improve accountability, you find that everybody says they want more accountability, but nobody wants kids to take standardized tests.” Now she faces a campaign in which she will be forced to defend an agency she doesn’t respect against George W. Bush, who wants to abolish it.

– Disaster: The Texas Department of Insurance. Fore years the insurance industry has pooled its data on automobile-liability and commercial-property losses in Texas and used this information to ask state insurance regulators for rate increases. For years pro-consumer politicians have contended that this practice amounts to collusion and price-fixing. Richards’ 1991 insurance reform, passed over strong industry objections, banned this sharing of information by insurance companies and required them to report their data to the state. But this victory didn’t last. Richards’ appointees to the insurance board, headed by her longtime friend Claire Korioth, had two years to get the agency in shape to analyze the data. As the deadline approached, however, the agency, by its own admission, wasn’t ready to take over. The Legislature extended the old system of letting the industry collect its own information by four years. I saw Richards in the capitol cafeteria during her fight to salvage her reform, and she had her old fire back. “I’m at war,” she said, drawing the last word out for emphasis. But the performance of her agency had made the war unwinnable.

It is too harsh to say that the New Texas is a failure. The regulatory process is more open and less predictable than it used to be. Lobbyist no longer get tip-off calls from the governor’s office about upcoming appointments and other decisions. Richards’ appointees have reined in many of the too-cozy relationships between agency employees and the private sector, such as highway commissioners and highway contractors. Incremental change has been achieved; big changes remain elusive.

What the New Texas has not achieved is the discovery and development of new leaders for the state—in other words, more John Halls. This mission of the New Texas was one of the main reasons Richards ran for governor. Now it has virtually been abandoned in favor of caution. Richards has endured too many humiliations at the hands of her own people; after Guerrero and the insurance board, there were high-profile resignations at the prison board and the highway commission. As a result, says a Richards friend, “She is risk-averse.” Better to appoint a stolid but clean Bob Krueger to the U.S. Senate, even if he loses, than to take a chance on a fresh face. Better to appoint a household name like Bill Hobby to the Parks and Wildlife Commission than to take a chance on someone who might raise objections to hunting, as a previous appointee of Richards’ did. “I’ve always said,” Richards told me, “that in politics, your enemies can’t hurt you, but your friends will kill you.”

Another group of Richards’ friends who have contributed to the decline of her morale is her senior staff. It is a strange and unwieldy group: a lot of ideologues with responsibility for policy issues, and a few practical politicians, but almost no one with the skills that are essential for a modern political staff—evenhanded expertise about complicated issues and the ability to create a credible public image for their leader. The result is that Richards doesn’t have enough information to be more than a cheerleader on many legislative issues, and she remains a personality politician who has not gotten the word out about her accomplishments.

The ideologues came from advocacy groups (primarily environmental, consumer, and health organizations) who helped elect her. Many of them were also her friends. They have caused Richards no end of grief inside the small world of the state capitol. “They had an agenda of their own,” says a former Richards aide. “They were loyal in their own way, but they were such zealots that the governor’s best interests were submerged to their causes.” The staff was the initial cause of Bob Bullock’s persistent hostility toward the governor. “Our staff wanted to force Bullock’s staff to do things,” says the former aide. “They thought the governor could dictate whatever she wanted.” In another instance, one senator got so angry at Richards’ environmental aide in 1991 that he made an obscene gesture to her after passing an unfriendly amendment. With a few exceptions—notably the three chiefs of staff during Richards’ tenure—the staff gets no respect from the insiders. And the chiefs have found it increasingly difficult to control the ideologues.

Richards knows that her staff isn’t helping her. She grumbles about them in the office and to other politicians. Once she even proposed in jest to swap staffs with another statewide officeholder. “She’s lonely,” a friend of Richards’ told me. “There’s nobody up there she can talk to.” As her sense of realism about government has increased, she has less and less in common with the ideologues. They contrast unfavorably with her description of John Hall: “He understands the concept of government that not many people in politics understand. You don’t get everything you want. The best you can do is lay the groundwork. You can grab what piece you can when you can. John Hall has done that.”

The mystery is, why does she tolerate a staff that is a liability to her? “The staff was young and ideologically committed,” she told me. “I wanted to teach them how to become statesmen and not advocates.” She paused. “Some of them have done a better job than others.”

But the desire of an old schoolteacher to turn her office into a classroom is not the only reason why Ann Richards keeps her staff around. I realized this at the beginning of our interview, when I mentioned that I would have to leave at noon to attend a Weight Watchers meeting with my wife. Richards pounced on the remark: “What’s it like? Do you sit in a circle? What do you talk about? Who’s in charge?”

Ann Richards, as everyone knows, is a longtime recovering alcoholic. Some of her friends say that her experience at Alcoholics Anonymous is one of her favorite topics of conversation. That was the comparison she was seeking: How is Weight Watchers like AA? “You know what AA is for, don’t you?” she asked. “It’s not to tell you to stop drinking. It’s to remind you of who you were.”

So it is with her staff. They remind her of who she used to be politically, and that is why she won’t—why she can’t—get rid of them.

She is not that person anymore. She has lost the faith in government solutions that is required of the true liberal. The issues she will talk about during the current campaign are economic development and crime. She will say that Texas has half a million new jobs since she took office and that she has built more prisons than any other Texas governor. She will say, as she said to me, “There’s a new pride in Texas now, a feeling that this state is good again. We have laid in place the foundation for Texas to become the largest free trade zone in the world.” A Republican could run for governor on Richards’ two main issues. Indeed, one did. His name was Clayton Williams.

Ann Richards’ message will be that Texas is doing well. George W. Bush’s message will be that it is not. He will argue, as he did on the night of his primary election victory, that juvenile crime, property taxes, and education bureaucrats are out of control. He will be the candidate of change, but he carries a heavy burden of proof about whether there is any reason to believe that he can make it happen.

The problem for Ann Richards is not so much Bush as it is herself. Who is she, really? What does she believe in anymore? What does she say to inspire the old Democratic constituency? It is an article of faith among liberal Democrats that moving to the center is a losing tactic. The only way to get the turnout necessary to beat a strong Republican, the argument goes, is to bring out the Democratic masses by promising to make their lives better. Ann Richards used to believe that—before she became sadder and wiser.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ann Richards

- Austin