Sam Rayburn was one of the most powerful Texans of the twentieth century. A Democrat, he was first elected to Congress in 1912, and he represented the Fourth Congressional District, a slice of the blackland prairie of North Texas, for 48 years. He was speaker of the House in every Democrat-controlled Congress from 1940 until his death, in 1961, making him the longest-serving speaker in American history.

Rayburn grew up on a forty-acre cotton farm in Fannin County and knew the backbreaking labor of chopping and picking cotton as a boy. When he was fifteen, he heard Congressman Joe Bailey speak in Bonham, and on that day he decided he wanted to study law and become a congressman. He pursued that ambition relentlessly. Once in Washington, he built up an unrivaled reputation among his fellow congressmen for fairness, integrity, loyalty, and political skill. One source of Rayburn’s unprecedented power after he became speaker was his extensive network of reciprocal friendships, which stretched across all branches of government.

Rayburn’s boyhood produced a wide streak of populism in him. He hated the abuses he saw visited on his rural neighbors by railroads, banks, and utility companies. He supported Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, was instrumental in passing legislation that regulated corporate securities and utilities, and remained an opponent of the business establishment all his life.

Rayburn was an atypical congressman. He refused gifts, even meals, from lobbyists as well as ordinary taxpayers. When he died, his life’s savings totaled $15,000.

In Washington he lived simply, in a rented three-room apartment near Dupont Circle, and walked the two miles to the Capitol every day. He was never part of the social scene. Texas congressman Marvin Jones told Rayburn biographer D. B. Hardeman, “Sam never cared much for the foppery and make-believe of Washington social life. He’d much rather talk politics with a bunch of men than go to some party.” Outside of his work in the House of Representatives, Rayburn did not really like the atmosphere of Washington. He once wrote, “It is a selfish, sourbellied place, every fellow trying for fame . . . and ready at all times to use the other fellow as a prizepole for it.”

The place Rayburn loved best was Bonham, where in 1916 he built a two-story frame house on 120 acres of land that he and his brother Tom had purchased. Every year, as soon as Congress adjourned, Rayburn took the train to Bonham, where he lived at what he called the Home Place with his mother and various other family members, traveling around his district, visiting constituents and friends, and overseeing his herd of dairy cattle. The Home Place had one telephone, which sat on a table in the downstairs hallway and was probably installed when electricity reached the farm, in 1935. Rayburn talked to presidents on that telephone.

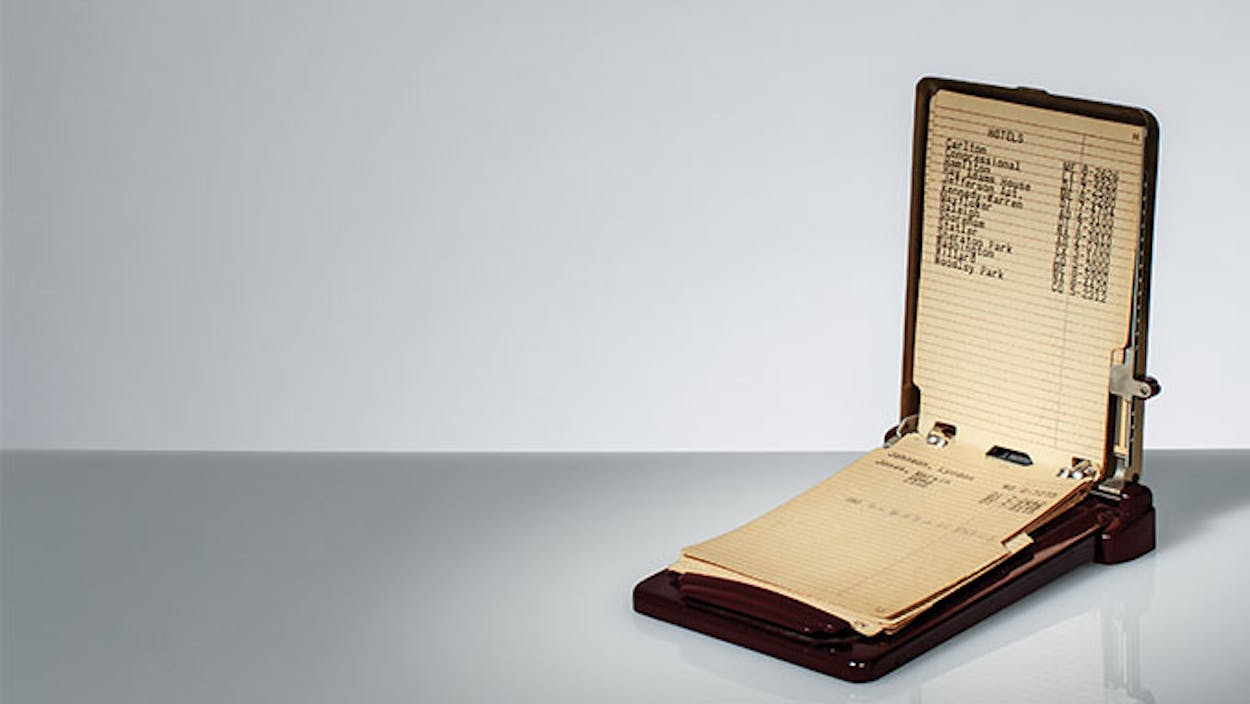

Rayburn’s house is now a museum, furnished exactly as it was at the time of his death and operated by the Texas Historical Commission. One of its most telling artifacts is a plastic-and-metal telephone index book, the kind in which a pointer moves down the cover to an embossed letter of the alphabet, opening to the page that corresponds to that letter. The book is called a Bates List Finder, and it contains 46 names. The curator at the Sam Rayburn House has determined that Rayburn used it between 1953 and 1955, during the Eisenhower administration. The book was kept on the hall table beside the telephone.

The numbers include Washington hotels, the Washington Western Union office, and a Washington florist. The others are for people from whom Rayburn sought counsel or those whom he at least wanted to stay in touch with when Congress was not in session. Four of these were members of his congressional staff, including his chauffeur, George Donovan, a trusted friend and fishing companion; eleven were congressmen or former congressmen from Texas; and two were United States senators, Lyndon Johnson (his number is WO-6-7273) and Stuart Symington, of Missouri. (Rayburn did not have a high opinion of the other senator from Texas, Price Daniel, who had endorsed Eisenhower over the Democratic nominee, Adlai Stevenson, in the 1952 election.) Two others, Felix Frankfurter and William O. Douglas, were associate justices of the Supreme Court and Rayburn allies from the New Deal days. Two more numbers were those of Rayburn’s oldest political allies, Cecil Dickson and Bill Kittrell, both Texans who had been in Washington since the twenties. Dickson was a journalist and Kittrell a lobbyist who was once described by Texas congressman Wright Patman as “the only man I ever knew who was knowledgeable about every man who walked through the lobby of the Mayflower Hotel in Washington.”

Rayburn’s private phone directory is a guide to the inner circle of friendships that made him one of the nation’s most powerful men. All the personal numbers listed in it are those of Democrats, with two exceptions: Eisenhower’s secretary of commerce, Sinclair Weeks, and Vice President Richard Nixon. Weeks was important because he was responsible for all federally funded highway projects; Nixon was a necessary evil. Rayburn disliked Nixon so much—he once described him as “that ugly man with the chinquapin eyes”—that he apparently could not bring himself to write his name in the phone index. Instead, Nixon’s number is listed under the letter V, for “V-Pres.”

Sam Rayburn House Museum,

890 W. Texas Hwy 56, Bonham

(903-583-5558). Open Tue–Sun 9–4:30.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy