This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Charles Albright patiently waited behind an unbreakable glass wall, watching as the prison guard escorted me through three sets of steel-barred doors. “I apologize for not being able to shake your hand and say hello,” he said, formally rising as I approached his window in the visiting room. “They do not allow me to have face-to-face visits.”

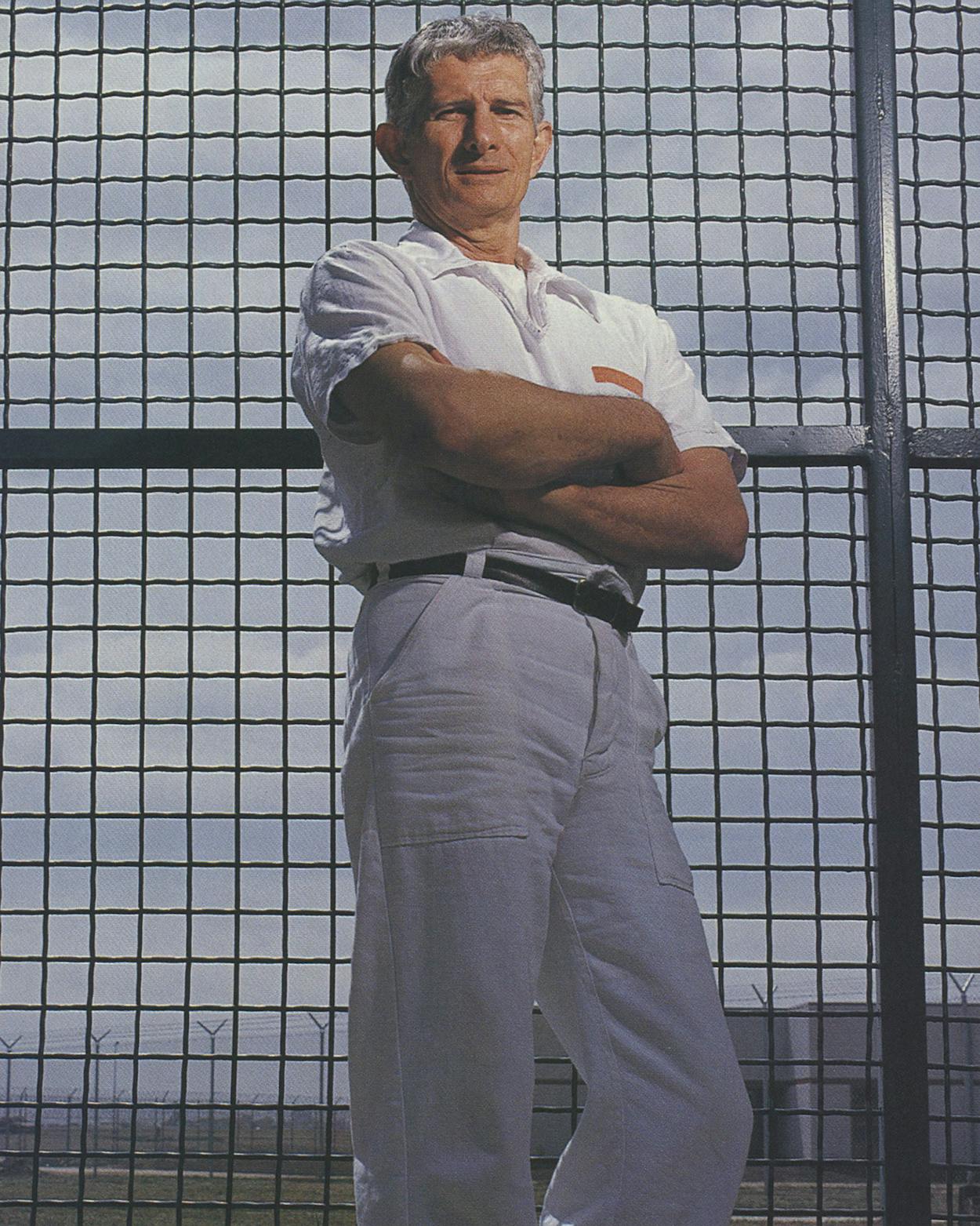

The steel doors clanged shut. Then the man whom the Dallas police had called the coldest, most depraved killer of women in the city’s history gave me a long gentle stare, his dark deep-set eyes never wavering, an encouraging half-smile on his lips. At 59, he had a finely sculpted face and carefully groomed gray hair. Even in his prison uniform, he looked positively distinguished. “Ask me anything you want,” he said. “I’m not going to tell you anything that’s not true.”

Throughout his life, Albright had been described by many who knew him as the portrait of happiness, untroubled and troubling no one. He was, they said, a kind of Renaissance man—fluent in French and Spanish, a masterful painter, able to woo women by playing Chopin preludes on the piano or reciting poetry by Keats. It was simply impossible to believe that he could have viciously murdered three Dallas prostitutes in late 1990 and early 1991. The person who should have been arrested, Albright’s friends and lawyers insisted, was Axton Schindler, a paranoid, fast-talking truck driver who lived in one of Albright’s rental homes. The evidence pointed to him, they claimed, not to their beloved Charles Albright. Perhaps Albright was a touch eccentric, but he was certainly harmless; he was even squeamish when it came to violence.

“You won’t find any woman who’ll say anything other than that I was always a perfect gentleman in their presence,” he said softly. Behind the glass wall, he wore an almost childlike expression—weak and perplexed and, yes, oddly appealing. “I was always trying to do things for women. I would take their pictures. I would paint their portraits. I would give them little presents. I was always open for a lasting relationship.”

In most cases, serial killers are brutal, woefully uneducated young men, lifelong sadists who kill for their own twisted reasons. How, then, could someone so charming, so exceedingly polite, suddenly decide in the later years of his life to become a blood-thirsty sex monster? “Look, I’ve known Charlie for thirty years,” sighed one Albright friend, a retired Baptist minister. “In all that time I think I would have seen his dark side slip out at least once. Believe me, if he really was a psychotic killer, he couldn’t have kept it a secret all this time—could he?”

December 1944: Life With Mother

He was known as the most good-natured, eager-to-please of children, a precocious boy who could do just about anything: name all the constellations in the sky, catch snakes without getting bitten, even perform a tap dance routine onstage at the famous Texas Theater. “Charlie was like a Pied Piper to the rest of us kids,” a childhood friend recalled. “We always wanted to see what he would do next. He was just so much damn fun.”

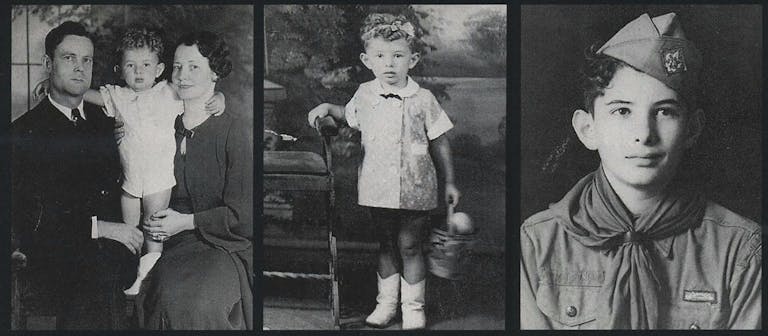

In 1933, when he was three weeks old, Charles was adopted by a young dark-haired woman, Delle Albright, and her husband, Fred, a Dallas grocer. The Albrights lived in the all-white middle-class neighborhood of Oak Cliff, then a beautiful residential area across the river from downtown. According to the story Delle would later tell Charles, his birth mother was an exceptional law student, just sixteen years old, who had secretly married another student and had become pregnant. When the girl’s father found out, he demanded that she annul her marriage and give up the baby for adoption; otherwise, he would cut her off from the family.

Delle Albright made sure that Charles knew she would never abandon him. She pampered her boy: She kept goats in the back yard so he could drink goat’s milk, which she said was better for him than cow’s milk. Yet sometimes her mothering went to extremes. When Charles was a small child, she occasionally put him in a little girl’s dress and gave him a doll to hold. Two or three times a day she would change his clothes to keep the dirt off him. Afraid that he might touch dog feces and get polio, she took him to Parkland Hospital to see the polio patients locked in huge iron lungs. “You can spend the rest of your life here,” Delle would solemnly tell her son. When he was less than a year old, Delle put him in a dark room as punishment for chewing on her tape measure. When he wouldn’t take a nap, she would tie him to his bed. When he wouldn’t drink his milk, she would spank him.

Indeed, people around the neighborhood talked about Delle Albright’s odd, grim nature. No one could ever remember her buying herself a dress. She kept a scarf over her head and wore clothes from Goodwill. Although she and Fred were far from poor, she usually scrimped at mealtimes, even picking up the old bones the local butcher threw in a box for his dogs. She could use them, she would say, for soup.

Not that Charles ever openly complained. He always appreciated that his mother taught him manners. Delle told him to speak politely about other people or “say nothing at all.” She told him to respect women, especially when it came to sex. She lectured him about the way his father acted “greedy” with sex: Whenever Fred saw her in the bedroom in her bra and panties, he tried to grab her. She was going to have none of that, and she was going to make sure Charlie never tried anything like that with his girlfriends either. As he grew older, she insisted on chauffeuring him every time he was on a date. She would even call the girl’s parents to let them know that her son would not do anything untoward.

If Delle seemed overprotective, friends said, surely it was because she had never raised a child before. Charles himself recognized how fiercely she wanted him to succeed. Each morning, before the school bus arrived, she had him practice the piano for at least thirty minutes. She taught him so much reading, writing, and arithmetic that he was moved up two grades in elementary school.

Delle also introduced Charles to the world of taxidermy. When he was eleven years old, she enrolled him in a mail-order course—the Northwestern School of Taxidermy, taught by Professor J. W. Elwood. “You are beginning to learn an art that is second only to painting and sculpturing,” Professor Elwood wrote in the first book of lessons Charles received. “A true taxidermist must be an artist.” As Charles set to work on the dead birds he found, Delle was right beside him. She showed him how to use all the tools: the knife used to cut the skull, the little spoon used to scoop out the brains, the scalpel required to cut away the eyes from their sockets, the forceps that pulled out the eyes. She even skinned the first bird for him, teaching him not to cut too deep.

Dutifully, Charles spent hours on his taxidermy courses, stuffing and mounting his birds, making them look as life-like as possible. Then he would be ready for the crowning touch—the eyes. He used to go to a taxidermy shop and stare at the boxes and boxes full of gloriously fake eyes: owl eyes, eagle eyes, deer eyes. He loved their iridescent gleam. He wished he could collect them the way other boys collected marbles.

Yet Delle wouldn’t let him. Taxidermists’ eyes were too expensive, his frugal mother would say; there was a better, cheaper way. She would open her sewing kit, look for exactly what she needed, and get to work. Then she and her son would place the birds in the oak china cabinet in the front of the house.

They were, indeed, Charles Albright’s first works of art, just as the mail-order booklet had promised. Everyone who came to the house would peer into the cabinet to see what he had done. And there, peering back, would be his birds, beautiful, life-like . . . and blind.

The birds had no eyes. Instead, sewn tightly against their delicate feathered faces, were two dark buttons, each shimmering dully in the living room light.

“You never knew a prostitute in Dallas?” I asked.

He shook his head, baffled by the question. “Never! I knew absolutely none of them. At the time I was arrested, I couldn’t tell you the names of the motels they stayed in, any of the motels’ locations, or anything else. It is a crime that the police never put me on the lie detector to find out what I did know and what I didn’t.”

“Could the prostitutes possibly have seen you somewhere?”

“None of these girls had ever seen me. They never saw me drive slowly by like I wanted to pick somebody up. Believe me, if I had anything to do with any prostitutes in Dallas, I would tell you.”

December 1990: Mary Pratt

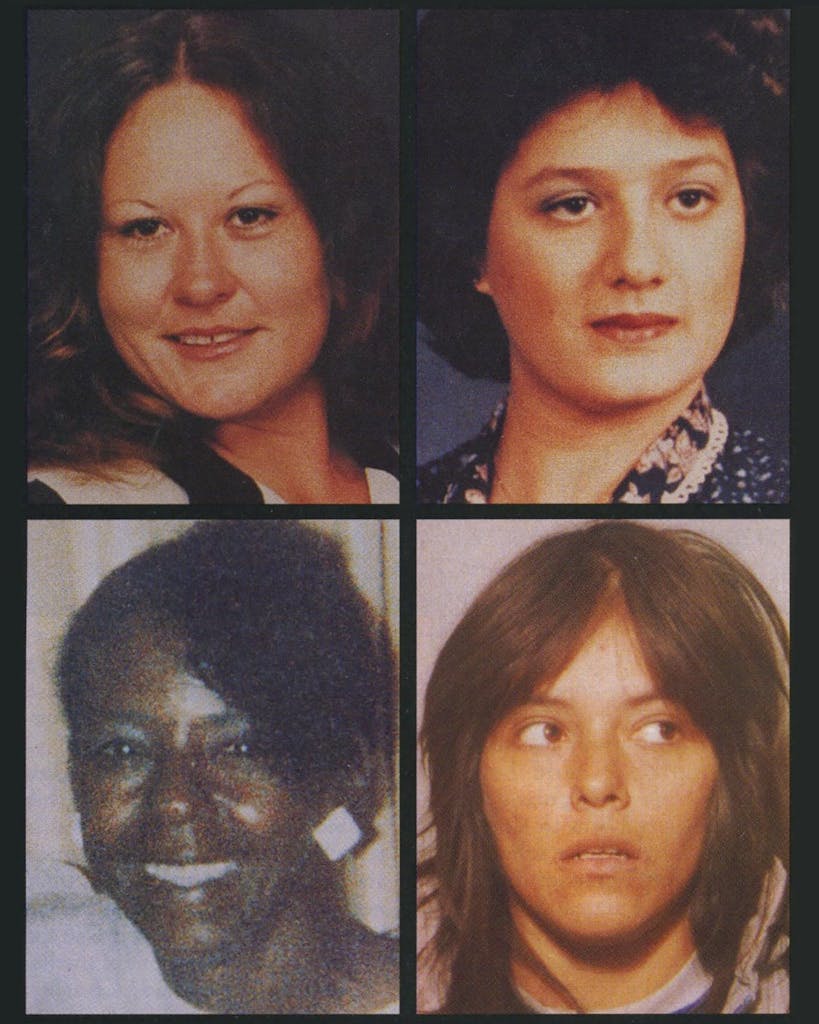

The first victim turned up in an undeveloped, almost forgotten lower-class area of far south Dallas. She was a large woman, 156 pounds, naked except for a T-shirt and a bra, which had been pushed up over her breasts. Her eyes were shut; her face and chest were badly bruised. Apparently, the killer had thought it best to beat her before firing a .44-caliber bullet into her brain. A resident of the neighborhood was so horrified by what he saw that he rushed inside his home and brought out a flowered bed sheet to cover the body.

A police officer on the scene immediately recognized the woman as Mary Pratt, age 33, a veteran prostitute who worked the Star Motel in Oak Cliff. While it was not unusual for the “whores of Oak Cliff,” as the police called them, to get their share of beatings—almost nightly, a girl would complain about a trick “jumping bad” on her, punching her, kicking her, even trying to run her over with a car—for a whore to be murdered was unusual, especially when it happened to be someone as well liked as Mary Pratt. Mary wasn’t one of the brazen hookers who stood in the street and flagged down tricks. Because she rarely had any extra spending money—the money she got usually went for drugs—she never bought sexy clothes. Standing quietly on her corner she wore blue jeans, tennis shoes, and small T-shirts that showed off her breasts. Occasionally, at the end of a night, she asked one of her regulars to drive her to her parents’ home in the south Dallas suburb of Lancaster. Mary’s parents—older retired people—never knew about her other life. They would call out good night as she climbed into her childhood bed.

Pratt’s file was handed to John Westphalen, a short, ruddy-faced homicide detective at the Dallas Police Department. With his thick East Texas accent and a wad of Red Man chewing tobacco permanently packed in his cheek, Westphalen looked more like a rustic county sheriff than a street-smart urban cop. In homicide circles he was something of a character: Defense attorneys loved to complain about his blustery, intimidating interrogation tactics. But Westphalen was also one of the department’s most tenacious investigators. He took one look at the Pratt file and realized the case would depend more on good luck than on good detective work. Pratt’s killing was a “dumped body” case—one of the hardest types of murders to solve. She had obviously been killed in one location and dumped somewhere else. There were no witnesses to either the killing or the dumping, no murder weapon, little forensic evidence, no fingerprints, and no apparent motive. Considering the kind of felonious characters who nightly swing by the Star Motel, Mary Pratt could have been shot by just about anyone.

Accompanied by his partner, homicide detective Stan McNear, Westphalen drove to the Dallas County medical examiner’s office to watch the autopsy of Mary Pratt. It was a routine trip; both men knew the autopsy would show a gunshot wound as the cause of death. As Dr. Elizabeth Peacock, one of the staff’s younger pathologists, put down her coffee cup to begin the examination, Westphalen and McNear stood a short distance from the blue plastic cart where Pratt’s body lay. Peacock noted the needle tracks on Pratt’s arms, the Playboy bunny tattoo on her chest, the bullet hole in her head. She opened Pratt’s right eyelid. Then she opened the left.

“My god!” she exclaimed. “They’re gone!”

There were no eyeballs, no tissue—nothing. Mary Pratt’s eyes had been cut out and removed so carefully that her upper and lower eyelids were left undisturbed. Peacock was dumbfounded. This was not an operation taught in medical school. The killer had to know how to slip a knife around the eyes, making sure not to injure the adjoining skin, and then cut the six major muscles holding each eye in the socket, as well as the rope-tough optical nerve. With the eyelids shut, it was impossible to tell the eyes were missing. Surely, whoever did this had to have had a lot of practice on someone, or something, else.

Quickly Westphalen contacted the FBI’s Violent Crimes Apprehension Program unit. Through its computers, the FBI keeps data on the nation’s most unusual, depraved mutilations—bodies chopped up, organs removed, even eyes punctured with a knife as a result of a frenzied attack. But an FBI agent told Westphalen that he found no listing anywhere of such a surgically precise cutting.

Longtime Dallas cops take pride in acting utterly unaffected by anything that comes their way. But this time, Westphalen couldn’t help it.

“What kind of person,” he asked McNear, “would want a girl’s eyeballs?”

September 1952: Class Clown

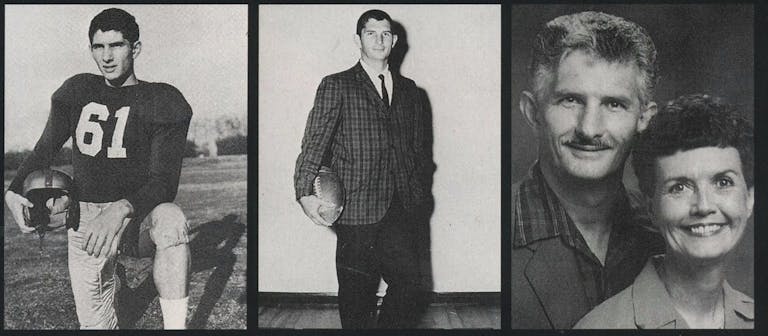

When Charlie Albright transferred to Arkansas State Teacher’s College in Conway, Arkansas, it didn’t take him long to become one of the school’s most popular students. He was remarkably well rounded: president of the French club, business manager of the yearbook, member of the school choir, halfback on the football team. When he signed up for a drawing course, the art professor was so impressed with Charlie’s good looks that he made him the class model.

Yet Charlie wasn’t known as just a goody two-shoes. He was the all-American fraternity boy, a great college prankster. One time he sneaked into the home economics building, got a load of food out of the refrigerator, and cooked a steak dinner for his buddies. Another time, on a dare, he broke into a physics professor’s office in the middle of the day, picked the lock on his cabinet, stole what was known around school as “the unstealable physics test,” raced downtown to make a copy of it, and had the test back in its place within an hour. The professor, who was teaching a class next door, never suspected a thing.

Frankly, Charlie Albright had to feel some relief in being away from home. He was considered a very bright boy in Dallas—he graduated from Adamson High School at fifteen—and he was something of a celebrity. When Charlie was fourteen, Delle and Fred purchased a piece of property in their neighborhood and gave it to Charlie. Charlie sold it to buy more lots, and the Dallas Times Herald published a story about him under the headline WORLD’S YOUNGEST REAL ESTATE MAN AMASSING NEST EGG FOR COLLEGE. Yet Charlie’s love for mischief had tainted his reputation. He had received bad deportment grades in school for shooting rubber bands and crawling out of study hall. He had “accidentally” set fire to his chemistry teacher’s dress. And he had flunked a few courses because he was “too bored” to study. (Of course, if his mother had found out, he would never have heard the end of it. So he sneaked into the school office, filched some report cards from a desk, filled them in with all A’s, and proudly showed them to his parents—his teachers’ and principal’s signatures perfectly forged.)

It was minor stuff, really. It wasn’t like he went to jail. As Charlie himself would later explain, “I just didn’t know what I was doing. If anybody tells the truth, they will say I never did a mean thing in all my life. But I did a lot of mischievous things just to show off for the older kids.”

Well, there was the time he was caught breaking into a neighborhood church. Then there was the time he was caught breaking into a little store and stealing a watch. And there were the visits he and his mother received from Alfred Jones, a twenty-year-old psychology student working part-time as a Dallas County juvenile probation officer. But what did Jones know back then? And what right did Jones have to say, forty years later, when he was a well-known psychologist in Dallas, that of the dozens of juveniles he saw back in the forties, the one he remembered most clearly was Charlie Albright? “He could divorce reality sufficiently from his value system,” Jones said, “so that he could tell you something false and at the time actually believe he was telling you the truth.”

Maybe, one of Charlie’s relatives said, he pilfered things from stores because his mother was so stingy. Or maybe he just wanted to rebel against her. Granted, Delle Albright did whatever she could to keep a close watch on her son. She took him to the Methodist church each Sunday. She made him go to bed, even when he was in his teens, at eight each night. Whenever she chauffeured him on a date, she watched him so closely that he would joke about the way she drove “with her eyes on the rear-view mirror.” Charlie loved his mother—that much was clear. But there were little things that sometimes bothered him. He was never certain, for example, that his biological mother had been the brilliant law student that Delle claimed she was. He so hated Delle’s cooking that he would stuff his food on a ledge under the table or give it to his dog. Delle fussed over him so regularly, he said, that he began to get headaches. (Delle decided the headaches were from bad eyesight and promptly made Charles wear glasses, even though he had twenty-twenty vision.)

Yet Delle couldn’t protect Charlie the first time he left home. Right after high school, he enrolled in North Texas State College in Denton—but by the end of his freshman year, he was arrested for being a member of a student burglary ring that broke into three stores and stole several hundred dollars’ worth of merchandise. Charlie swore he stole nothing. The other boys, he said, had asked him to keep some things in his dorm room for them. How was he to know the things were stolen?

Delle Albright went to the store owners and tried to reimburse them for what was taken. She tried to persuade the judge to let her act as Charlie’s lawyer. She even asked that she take his place in prison. Yet the boy went to prison for a year, spending his eighteenth birthday there. Delle, meanwhile, worked to keep the matter hushed up, so that no one in her neighborhood knew that Charlie Albright had become a convicted felon.

Arkansas State Teacher’s College was Charlie’s chance for a new start. As he told a probation officer, he was going to mend his ways. He began to date a lovely young English major, Bettye Hester, and made plans to marry her. He did truly brilliant work in science; although he hardly studied, he made an A in his human anatomy course. It was said around school that Charlie Albright was going to go far. He even talked about going to medical school and becoming a surgeon.

But Charlie never stopped playing the role of class clown. Of all his great pranks, no one would forget the one he played on his friend Andrew (not his real name). In a fit of anger, Andrew had broken up with the most beautiful girl on campus, a woman with almond-shaped eyes. After the separation, he tore up several photographs of her and threw them in a trash can in his dorm room. Weeks later, Andrew got a new girlfriend and asked her for a photo. One night, while Andrew was staring at his new girlfriend’s picture, he realized that something was wrong. He looked closer. It seemed that her eyeballs had been cut out and replaced with—Good Lord!—the eyeballs of his old girlfriend. In disbelief, Andrew looked up at the ceiling. There staring down at him, was another pair of his old girlfriend’s eyeballs. More eyeballs were above the urinal in the men’s bathroom down the hall. No matter where Andrew turned, he was confronted by the sight of his old girlfriend’s almond-shaped eyes.

The story soon raced through school. That jokester Charlie Albright had pulled the old photographs out of the trash and saved her eyeballs for just the right moment. Did any of his fellow students, in retrospect, find the stunt a bit strange? Of course not, they said. It was pure Charlie. Who else could have been so inventive?

“Why do you think the eyeballs were missing?” I asked.

“I don’t understand either.” He sighed. “Why the eyeballs?”

“Well, what kind of person would be able to cut out the eyeballs of some hooker?”

“Someone who is sadistic? Just one mean son of a gun? I don’t know the purpose behind it, unless that person thought the women wouldn’t be able to see without their eyes in the next world—which is sort of ignorant.”

December 1990: A Clue

Because the police had not released any information about Mary Pratt’s missing eyeballs, her death had only warranted a two-paragraph story in the back sections of the local newspapers. In fact, when patrol officers John Matthews and Regina Smith began their daytime shift on December 13, just a few hours after Pratt’s body was found, they had not even heard about the crime.

Only two and a half months before, the two officers had been assigned to a newly created beat on Jefferson Boulevard that included Pratt’s streetwalking territory. Once the most popular shopping district in Oak Cliff, Jefferson had deteriorated over the previous 25 years, a victim of urban blight. Some storefronts were shuttered; others were barely profitable. The Texas Theater, infamous for being the site where Lee Harvey Oswald hid out after the Kennedy assassination, was padlocked. Matthews and Smith’s assignment was to provide a police presence for the area—to become acquainted with the merchants, shake a lot of hands, and crack down on small-time crime such as burglary, car theft, shoplifting, and prostitution. In police circles, it was far from a glamorous beat. Other officers, used to the action of the streets, considered it more of a public relations position.

Each morning, Matthews and Smith began their day by cruising down Jefferson, herding the prostitutes back toward the Star Motel. On a busy day, about forty women—mostly black, some white, and a few Hispanic—worked the area, charging anywhere from $15 to $50 for a “flatback” (straight sex). The Star was not a high-class call girl operation; Matthews snidely called the forty-room motel “the prostitute condominium.” The women there, most of them drug addicts, would have sex in a customer’s car in a nearby alley or use a room shared with other prostitutes. Then, money in hand, they would walk down a well-worn dirt path to one of the nearby dope houses and purchase heroin or crack. After a quick hit, they would be out on the street again. Some hookers would work nonstop for two or three days—never changing their clothes, never even taking the time to eat—until they finally crashed back at the motel or in the house of their “sugar daddy” (a regular customer who cared for the woman enough to provide her with food, clothes, and a place to sleep).

Such a dreary scene did not faze Matthews, a stocky, no-nonsense 28-year-old; little on the streets did. The son of a patrol officer in New York State, he had grown up with cops-and-robbers stories. He had been with the Dallas Police Department since he was 21, when he went to work patrolling Harry Hines Boulevard, one of the city’s high crime and prostitution areas. On the other hand, when 31-year-old Regina Smith decided to become a police officer, she had never fired a gun, seen a dead person, or even been in a fight. She was a former supermarket cashier, a graduate of a two-year fashion merchandising college, and the single mother of a 6-year-old child. Nonetheless, inspired by a newspaper story about the need for more black female police officers, she entered the Dallas Police Academy in 1988. Her instructors berated her for wearing too much jewelry, mocked the way she shot a gun, and laughed when she couldn’t finish her push-ups, but she refused to quit. After graduation she was assigned to one of the rougher night shifts—and still she wouldn’t quit.

On the Jefferson beat, Smith discovered she had a knack for talking to prostitutes. She wanted to talk to them; she felt it was her duty as a police officer to try to improve people’s lives. “Tell me, girl,” she would say to a new prostitute, “what are you doing whoring out here? You know you can make more money working at Burger King than you do here.” She even started a “hook book,” a kind of photo album that contained the mug shots of the whores on the street. She would wistfully leaf through her hook book the way some people pore over their high school annuals.

On this particular morning, Smith was not surprised to see Veronica Rodriguez, a brazen charcoal-eyed prostitute who would try to flag down tricks even when she knew the cops were watching. Usually, when she spotted Matthews, she would lean forward so he could see her cleavage and say, “How ya doing, Officer?” Rodriguez, barely 26 years old, had lived a miserable life. She had been arrested for prostitution numerous times, once when she was nine months pregnant. Although that baby was stillborn, she was the mother of at least one child—a baby born on a raggedy bed in a whore motel down the road from the Star.

As Matthews pulled the squad car alongside Rodriguez, Smith rolled down her window. She noticed a nasty gash across Rodriguez’s forehead and what looked like a thin knife cut across the front of her neck. “Girl, what happened to you?” she asked. “Don’t arrest me,” Rodriguez gasped. “I almost got killed!”

Rodriguez told the officers that the previous night, she had been picked up by a trick, driven a long way south to a field, and raped. The man—a white man, she said—then tried to kill her, but she escaped and ran toward a house. The man at the house just happened to be someone she knew. He also just happened to know the man who was trying to kill her.

Matthews and Smith gave each other a look. Rodriguez was a notorious liar. No doubt she had been in some kind of fight, but in the middle of nowhere she ran right into the house of someone she knew? This was probably another of Rodriguez’s “pity stories,” which she often told the cops so they would feel sorry for her and leave her alone.

Yet two days later, on an afternoon drive past the Star, Matthews and Smith saw Rodriguez again. She was sitting with a balding middle-aged white man in the cab of an eighteen-wheeler. While Matthews went to one side of the truck to get Rodriguez and escort her to the squad car, Smith went to the other side to speak to the man. She asked him for his driver’s license, which he produced: His name was Axton Schindler, of 1035 Eldorado. When Smith ran Schindler’s name through the computer, he came up clean, except for some unpaid traffic tickets. Suddenly, Rodriguez started shouting, “Oh, don’t arrest him! That’s the man who saved me from the killer! That’s him!”

The officers looked at the address again: 1035 Eldorado. It was not out in south Dallas, where Rodriguez’s attack allegedly took place. It was in an Oak Cliff neighborhood, just a five-minute drive from the Star. The man—a sort of nervous guy who spoke incredibly fast—said he had no idea what Rodriguez was talking about. He said he had known her for years and was just giving her a ride to the motel. He didn’t protect her from any killer. He didn’t even have sex with her. He was just a long-distance truck driver doing her a favor. Rodriguez, the officers decided, was lying once again. They carted her to jail for prostitution and hauled Schindler in for his unpaid tickets.

Although Matthews and Smith would not know it for months, a clue to the murderer’s identity had fallen right in their laps.

September 1969: Con Man

Charles Albright was 36 when he began teaching high school science in Crandall, a small town east of Dallas. The principal at Crandall, who had been looking for a teacher the entire summer, was ecstatic when the astute young man called him up right before the school year was to begin. According to his college records, Charles Albright had a master’s degree in biology from East Texas State University and was working on another master’s in counseling and guidance. He was also about to enter ETSU’s Ph.D. program in biology.

Albright’s students found him fascinating. On field trips, he could recite, in flawless Latin, the scientific name for every plant he came across; he could split open a rotted log and talk about each insect he found inside. He drove a green Corvette to school and wore lizard-skin shoes. (A few girls, smitten by his charm and masculine looks, wrote him love letters.) He even helped coach the football team. After a heroic play by one Crandall player won a game for the school, Albright lifted him up and carried him off the field.

How, the principal would later ask, was anyone supposed to know that the promising young teacher had forged all of his transcripts? He was simply flabbergasted when an ETSU official told him that Albright had never even earned a bachelor’s degree. Everything—his degrees, his teacher’s certificate—had been faked. Apparently, he had slipped into three different offices at East Texas State, grabbed all the necessary forms, copied them, added his name, forged signatures, and then sneaked them back into the files. He had even stolen the registrar’s typewriter so the typeface on his records would look the same. Had an ETSU administrator not realized that he had never met the Charles Albright whose name kept popping up on the school’s list of graduate students, Albright would have gotten away with the scam.

When Albright was confronted, he grinned ruefully and admitted to the crime. He needed to bend the rules a little, he explained, in order to get a teaching job. After he quit Arkansas State Teacher’s College—well, okay, he was kicked out for being caught down at the train station with suitcases full of stolen school property, including his own football coach’s golf clubs—he didn’t think he was going to get a second chance to prove how smart he was. By then, he had married his college sweetheart, Bettye, and she had given birth to their daughter. Frankly, he didn’t have time to begin all over at a university. It was a crying shame, he said. If only he could have finished his degree, there was a professor at Tulane University in New Orleans who would have hired him to do biology research.

Because the forgery was a victimless crime—and because Albright himself, according to one ETSU administrator, was such a nice, repentant fellow—the university decided to keep the transcript scandal out of the newspapers. It was embarrassing, after all, that a school could get bamboozled. Albright pleaded guilty to a fraud charge and received a year’s probation.

As the seventies began, Albright was back in his old Dallas neighborhood with his wife and daughter, living in a house not far from his parents’ home. Once again, no one had any idea of what he had done. The Charlie Albright the neighbors knew was a happy-go-lucky figure who could master anything but simply didn’t care about settling down in a nine-to-five job. He had some money from his parents, and his wife had a job as a high school English teacher. He was free to latch on to one new project after another; he rarely had a job that lasted longer than three months. He worked as a designer for a company that built airplanes. He worked as an illustrator for a patent company. He was a well-regarded carpenter. He collected wine bottles from the famous Il Sorrento restaurant in Dallas, hoping to start his own winery. He bought a lathe and made baseball bats. He collected old movie posters. He regularly went to the Venetian Room at the Fairmont Hotel to get autographs from the stars performing there. On a lark, he went to a Mexican border town and became a bullfighter—“Señor Albright from Dallas,” the posters read.

Albright still had a Pied Piper–like ability to captivate people. After visiting a friend who worked at the beauty salon in a Sanger Harris department store, Albright promptly went off to beauty school, got his beautician’s license, and then persuaded the salon to hire him, with no experience at all, as a stylist. Albright took to calling himself Mr. Charles. He would spend at least an hour with each woman to get her hair exactly right.

When Albright told his stylist friend that he was also an accomplished artist, the friend paid him $250 to paint a picture of his wife. Albright was indeed a good painter; self-taught, he had won a prize at the Texas State Fair for his portrait of a dark-haired woman in a long green gown. His goal, he said, was to be like Dmitri Vail, the famous portrait artist of Dallas.

Albright worked for weeks on the woman’s painting without finishing. He insisted that he needed to keep working on one special feature, the most difficult part of the painting. Tired of waiting, the friend decided to go to Albright’s house to look at the work in progress. There, in the living room, was the six-by three-foot portrait. It was richly colored and remarkably realistic. The woman’s hair, her mouth, her nose, her ears, her neck—everything was finished. Well, not everything. The stylist stared curiously at his wife’s painting. In the center of his wife’s face were two round white holes.

After all this time, Albright hadn’t even begun working on the eyes. It was as if something held him back, as if he preferred the portrait to remain as it was on his living room easel. “Charles,” asked the friend, “when are you going to paint the eyes?”

“When I am ready to,” Albright replied.

Months later, Albright finally painted the eyes. He then painted them again, to get them just right. He painted the proper shadows under the eyelashes; he gave the eyelids just the right droop in the corners; he shaded the eyeballs to make them look perfectly round. When Albright was finished, his friend could not believe how well the painting had turned out. It was, he realized, a mesmerizing portrait—especially the eyes. His wife’s eyes were so perfectly recreated that they seemed to follow a person across the room

“There’s no question you love eyes,” I said.

“Well, I do want to paint fine eyes. That’s every other artist’s weakness—they can’t paint eyes.”

“Would you ever love eyes enough to—”

“No, no, I’ve never taken the eyes out of anything. I’ve never had the desire to. To me, what matters is what the eyeball looks like in the woman’s face, or the guy’s face—not what the eyeball itself would look like.”

“Could you figure why someone might want to keep the eyeballs? Would they want them as a sort of a souvenir?”

“I don’t think anybody would want to keep eyeballs. That would be the last thing I would want to keep out of a body. It would be a hand or a whole head, maybe, if you were a sick artist and you thought the woman was fabulous. You might not want to see that beauty go to waste.”

February 1991: Susan Peterson

The second victim was found on a Sunday morning, on the same south Dallas road where Mary Pratt was dumped. Like Pratt, she was mostly naked. Like Pratt, she was a prostitute. Her name was Susan Peterson, age 27. She had been shot in the head, chest, and stomach. Her eyelids were closed.

Because her body was discovered on the other end of the road, just outside the city limits, the jurisdiction for the case fell to the Dallas County Sheriff’s Department. A detective named Larry Oliver, who had not heard about the Pratt killing, was called to the scene. Eerily, the same scenario unfolded. Oliver accompanied the body to the autopsy room, where a pathologist began the standard external examination. The pathologist opened one eyelid, then the other. He motions for Oliver to come closer to the table. Oliver couldn’t believe what he was seeing: The dead woman’s eyes had been expertly cut out.

When the pathologist mentioned that the Dallas Police Department had had a similar case just two months earlier, Oliver did some checking. Within 24 hours he traveled to the police department’s homicide offices to see John Westphalen. Soon there were meetings with sergeants and lieutenants and with the chief in charge of homicide. While police officials deliberately avoided the phrase “serial killings” to describe what was happening—Westphalen kept referring to the killer as “a repeater”—everyone in the room knew what they were hunting for: a twisted, brilliant murderer, someone who dropped bodies on quiet residential streets, where they were certain to be found the next morning.

At that point, a contingent of detectives favored keeping a lid on the story. If the press discovered that the killings were linked and turned the spotlight on the Star Motel, the killer might get nervous and start picking up women from other areas. But homicide supervisors decided that the police department had a greater obligation to warn the community that it might be in danger—even if it meant warning low-dollar hookers. Besides, publicizing the case might bring in some leads. Lord knows, there was little else to go on.

As flyers were posted around the Star asking prostitutes to stay off the streets, detectives met with the press to discuss the two killings. Although no information was officially divulged about the missing eyes, word quickly leaked to reporters that the women’s faces had been strangely mutilated. “The guy was almost surgical in the way he did it,” one detective told a reporter. To the police department’s dismay, a media frenzy ensued. The prostitute murders sent the city’s imagination into overdrive; calls came in from reporters all over the country.

As John Matthews and Regina Smith sat in their squad car reading the front-page newspaper stories about the prostitutes’ deaths, they too were shaken. These were women from their beat, women they were supposed to protect. They knew Susan Peterson: She used to be the most beautiful white prostitute in Oak Cliff. Although her five years on the street had taken their toll—her once-alluring smile had turned winter-hard and her body had grown plump—she was still able to put on her brown go-go boots and denim miniskirt and pick up ten to twelve tricks a night. And she was a fearless hooker. She threatened other prostitutes who tried to work too close to her corner. She even cursed Matthews and Smith when they tried to move her off Jefferson Boulevard. Like a good pickpocket, she was an expert at clipping a trick—stealing money from his billfold while he was having sex with her. If the killer could get Peterson, Matthews and Smith said, then he could get any of the women. They surmised that the killer knew every corner of the whore district, all the alleys and all the streets. He was able to pick up Peterson and vanish within seconds. He also must have been one of her regular customers. Otherwise she never would have let her guard down. Certainly she wouldn’t have allowed him to shoot her three times. She would have pulled out a razor and fought back.

This time when Matthews and Smith pulled up to the Star, the prostitutes didn’t keep their distance. They poured out of their rooms, surrounded the squad car, and began to pass on their own personal lists of suspects. The women talked about their kinkiest tricks, the men who wanted to tie them up or whip them. Smith made her usual impassioned speech, asking the girls to get off the street, but the black prostitutes, at least, were not buying it. “He’s after the white girls, honey, not us,” they said. Oddly enough, the black prostitutes saw the killings as an opportunity for them to get more business.

And then there was Veronica Rodriguez. Rodriguez had been telling a lot of people—reporters, other prostitutes, and Matthews and Smith, as well as other officers—any number of stories since the killings began. At first, she said she had witnessed Mary Pratt being shot. Then she said she had met a man who had only bragged about having killed Pratt. Then she said she knew nothing at all about Pratt’s death. About her own rape in the south Dallas field, she no longer said the killer was white; now he was Hispanic. Then she said he might have been black. Almost everyone who spoke with her thought she was “brain-fried” from drugs.

What bothered Matthews, however, was that Rodriguez had never changed her basic story about being attacked. Usually, she would forget whatever pity story she had told the day before. Did someone really try to kill her in that field? Could the man who supposedly saved her, Axton Schindler of 1035 Eldorado, know the killer too? Or could Schindler have something to do with the killing himself? Could it be that the real reason Rodriguez was changing her story was simply because she was afraid?

Matthews and Smith didn’t know what to do next. They had already told the homicide division that Rodriguez claimed to have information about Mary Pratt. They had mentioned the attack and the possible Axton Schindler connection. With that, they figured they had done their job; it would have been way out of line for the two young officers to cross into homicide’s territory and conduct a murder investigation on their own. Later, Westphalen would say that he never got the officers’ tips. Among all the phone calls, all the messages, all the reports flooding in, the name “Axton Schindler” never crossed his desk, he said.

Whatever the case, a potential break was slipping away—and the killer was preparing to strike again.

March 1985: Dark Secrets

The incident was kept very, very quiet. There would be no trial, no headlines. The district attorney had arranged for him to serve a probated sentence of ten years, which meant no jail time. Probation was fine with him—just as it was in 1971, when he was arrested for forging some cashier’s checks, and in 1979, when he was caught shoplifting two bottles of perfume. In 1980, when he was sent to prison for stealing a saw from a Handy Dan, he had to serve six months. But then, at least, his mother could tell everyone that he was leaving Dallas temporarily to take an important job at a nuclear power plant in Florida.

This case, however, was different. If the news got out, it could humiliate him. Not that he was guilty, he kept saying over and over. He had never touched that little girl. The girl’s family was just looking for a scapegoat—and they had picked him, Charlie Albright, one of the most dedicated members of St. Bernard’s Catholic Church in East Dallas. He had first met the family in 1979, when he began singing in the church choir. People admired his voice, even if it was untrained. In one hushed service, he performed the tenor solo, “Comfort Ye My People,” from Handel’s Messiah. Soon he was acting as a Eucharistic minister, standing before the altar in a robe, reading Bible passages, helping with Communion—almost like an assistant priest, for goodness sake. He loved to help people; everyone knew that. The monsignor at St. Bernard’s called him Good Old Charlie. Albright was known to slip a $100 bill to someone who was down on his luck. After he met the little girl’s family, he brought them a big box of steaks. He dressed up as Santa Claus and gave the girl and her siblings presents. Did anyone seriously believe he would sneak into her bedroom and molest her?

The girl’s parents tried to keep the matter quiet—especially at the church—because they did not want to stigmatize their daughter. But they also wanted Good Old Charlie to pay. Albright worried that if he fought them, the story would leak. So on March 25, 1985, in a nearly empty Dallas courtroom, he stood before a judge and confessed to “knowingly and intentionally engaging in deviate sexual intercourse” with a girl under the age of 14. He was 51.

For the first time, Charles Albright’s mask seemingly had slipped. Was there, on the other side of his gentlemanly Jekyll-like personality, a kind of sexually perverted Hyde? Women who heard the story couldn’t believe it. After Albright dissolved what he called his loveless marriage to Bettye in 1975, he developed a reputation as an old-fashioned ladies’ man. He was still getting by with odd jobs and family money, but women saw him as a grand romantic figure, someone who showered them with flowers and music boxes and candy. To one woman, he recited from memory all 42 verses of “The Eve of St. Agnes,” by John Keats. To another, he gave a slew of presents, along with a fully decorated Christmas tree. Women found him virile and sexy; one said he could do six hundred pushups without stopping. Yet Albright never made a sexual advance toward a woman until she asked him to first—at least that’s what he proudly told his friends.

In late 1985, Albright fell in love with Dixie Austin, a pretty, shy widow whom he had met on a trip to Arkansas. It was one of the most romantic times of his life. At dinner, he charmed Dixie with stories about nature and art. He showed her the autographs he had collected from Ronald Reagan, Marlene Dietrich, and Bob Hope. He took her hunting in the country for salamanders. His dream, he told her, was to find a new species of salamander that could be named after him. Sex with Albright, Dixie later said, was gentle and satisfying. He never talked dirty to her, and he never wanted her to do anything that might be considered unconventional. He certainly did not sneak off and have affairs.

By the time he met Dixie, however, Charles Albright had already created another life for himself. Although he masterfully hid his secret from everyone who knew him, he was a veteran of red-light districts all over Dallas. To some prostitutes, he was a whoremonger—a regular trick. To others, like Susan Peterson, he was even a sugar daddy. At Ranger Bail Bonds, the company she used to bail her out of jail, Peterson listed Charles Albright as her cosigner on bond applications. On one form, she listed him as her best friend in the event that she skipped town and the bondsmen had to hunt her down.

There is also evidence that Albright was a friend of Mary Pratt’s long before she became a prostitute. In the early eighties, Mary lived in a south Dallas neighborhood where Albright’s parents had long ago invested in cheap rental property. At the time, Albright was temporarily living in one of the rental homes. According to several sources, Albright had a brief fling with one of Pratt’s female friends and brought that woman and Pratt over to his house for parties.

Other prostitutes say that when Pratt started turning tricks at the Star, Albright became one of her customers. Pratt told them that “Old Man Albright” was a good trick, willing to pay a little more than the going rate. Soon Albright was making the rounds. With some of the girls, he had a platonic relationship. He would pick them up, talk to them, take them to get a hamburger, and drop them back off, never even attempting sex. With others, he had standing sexual appointments—always in the afternoons, when Dixie was at work as a sales clerk at a gift shop in Redbird Mall.

Every Friday afternoon, for instance, he had sex with a married woman who hit the streets after her husband had gone to work and her children were at school. Albright, whom she called Pappy, felt sorry for her, she said: “He was a sweet gentleman. If I ever needed extra money, I would call him and he would drop it off.” But the married woman said that by late 1987 she had to put an end to her dates with Albright because he began to get more and more aggressive. She said he asked her to beat him—“to spank him like a child.” Another prostitute, Edna Russell, remembered meeting Albright when her friend Susan Peterson asked her to do a “double.” She said she and Peterson went with Albright into a motel room. There, he handcuffed them to the bed and began hitting them with a belt and an extension cord, all the while shouting, “Scream, bitch! You know you like it!”

Perhaps it was no coincidence that Albright’s life began to spin out of control after the death of his parents, Delle and Fred. Without them around to look out for him, a repressed part of Albright may have finally unleashed itself. He and Delle, who died of cancer in 1981, were not close in her last years. Delle was disappointed in the way her son had turned out, while Albright found her to be a pest—especially when she would bang on his door early on Saturday mornings to get him to help her with one of her little fix-up projects. But as his final gesture of devotion to his mother, Albright went out and bought a dress for the undertaker to put on her body—the first new dress he had ever seen her wear. Surprisingly, he wept at her funeral, wracked with grief or maybe guilt over the way he had let her down.

He also cried at Fred’s funeral a few years later. Frankly, it had not been until after Delle’s death that Albright and his father became close. Albright remembered how Delle constantly nagged at her quiet husband, bickering with him about problems around the house. With her gone, Fred seemed more relaxed. Several nights a week, Albright would take him to dinner at a nearby cafeteria.

After Fred’s fatal heart attack in 1986, Albright inherited at least $96,000, along with all of his parents’ homes and property in south Dallas. For what friends said were sentimental reasons, he kept the property in his father’s name. To bring in some extra money, he rented out one of the tiny ramshackle frame homes, on a street called Cotton Valley, to a truck driver named Axton Schindler. Known as Speedee because he talked so fast, Schindler was a singularly weird individual. He stacked the rooms of his house with trash up to three feet high. He put an automobile engine in the living room. He lived without electricity and running water: He used a Coleman lantern for light and bottled water to wash himself. Albright’s friends said he should get another renter, that Speedee was too unusual. But the always agreeable Albright, who had met Schindler through a female friend, said he wasn’t that bad of a fellow, so he let him stay.

At this point, Albright had made the decision to move back into the old family home in Oak Cliff, which, like the rental homes, was still listed in the property rolls under Fred’s name. Although the neighborhood had grown somewhat shabby over the years and the house was definitely in need of a new paint job, Albright said the place would do nicely. He brought his new love, Dixie Austin, down from Arkansas, and together they settled in for a quiet, romantic life.

The address of their home was 1035 Eldorado.

“You know Irv Stone, the head of the Dallas County forensic science department, which studies physical evidence found at crime scenes?”

“Yes,” he said. “We played on a softball team together. He was sort of a standoffish person. Everyone would call him ‘Dr. Stone.’ So finally I said something to him about my supraorbital foramen bothering me. He’d say, ‘Huh?’ I’d say, ‘You know, where the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve comes through and feeds my eyebrow up here. It’s really been bothering me.’ And Irv, sort of cocky, said, ‘I hate to inform you that I am not a medical doctor.’ I’m surprised he didn’t know his anatomy.”

“What were you describing, the area above your eye?” I asked.

“Yes, the little ridge there, right where the nerve comes through.”

March 19, 1991: Shirley Williams

John Westphalen had filled up four black spiral notebooks with notes on the prostitute murder case. He had gone back and reexamined the crime scenes. Special undercover units had been sent to stake out the prostitution areas and run computer checks on the license plates of vehicles that cruised by, just to see if the owners might have any unusual criminal records. Everything added up to zip. This was a killer in total control, a man who refused to panic. “We’ve got to answer three questions,” Westphalen said again and again at meetings about the case. “Number one, Why is he after prostitutes? Number two, Why were both bodies dumped on that same street? And number three, Why are those eyes cut out?”

Sitting around Westphalen’s battleship—gray metal desk in the heart of the fluorescent-lit homicide office, detectives started throwing out theories. Maybe the killer had gotten AIDS from a prostitute and was out for revenge. Maybe he believed the old superstition that a murderer’s image always remains on the eyeballs of the person he kills. Maybe he believed a dead person’s eyes would follow him forever. Or maybe the killer took the eyeballs to fuel some sexual fantasy. Maybe he wanted to eat them—or cook them. The only thing Westphalen knew for sure was that the killer came out late at night, was strong enough to drag those girls in and out of a car, and had surgical skills. He also probably needed a well-lit room to do his surgery. Hell, somebody said, maybe this guy is a whacked-out doctor.

Suddenly, in the early morning hours of March 19, the killer changed tactics. On Fort Worth Boulevard, another whore hangout a few miles from the Star, a black prostitute named Shirley Williams emerged from the Avalon Motel, where she worked as a maid during the day and turned tricks at night. According to another prostitute who saw her, Shirley was wearing jeans and a yellow raincoat and appeared to be in a stuporous drug high as she tottered alone on the sidewalk.

She was found at six-twenty the next morning, dumped on a residential street half a block from an elementary school in the heart of Oak Cliff. As children walked to school, they could see the naked woman crumpled against the curb. An unopened condom was beside her body. “Go look at her eyes and tell me if they’re there,” Westphalen said to the medical examiner’s field agent at the scene. The field agent flipped open the eyelids. “Gone,” he said.

Westphalen turned to his partner, Stan McNear. “We’ve got number three,” he said.

The autopsy on Shirley Williams’ body would show that the surgery had been hurried. The broken tip of an X-Acto blade was found embedded in the skin near her right eye. But there were still no witnesses, no murder weapon, no fingerprints. Worse, the killer had now murdered a black woman, and he had moved locations. Just as the detectives had feared, the publicity about the case had sent the killer away from the Star and his south Dallas dumping ground. There was no telling where he would hit again.

October 1990: A Son’s Vengeance

In the autumn before the killings began, Charles Albright was the model of domestic propriety. During the day, he put his carpenter’s skills to use around the house, installing new cabinets for the kitchen, adding a skylight in the bathroom. If he was preparing to become a modern-day Jack the Ripper, none of his friends or family had any idea.

But on October 1, Albright did something that, even for him, seemed a little peculiar: He took a job delivering newspapers in the middle of the night for the Dallas Times Herald. Albright told Dixie, who by now was his common-law wife, that he needed more spending money. He had never been good with his finances; in four years he had gone through his inheritance, and he had yet to get a full-time job. Because Dixie got a monthly annuity check and worked daily in the gift shop, she paid most of their bills. Dixie wasn’t exactly pleased with Charlie’s decision—she said she couldn’t get a good night’s sleep with him gone. But Albright said it would work out fine. He would wake up around three in the morning, deliver papers on an Oak Cliff route between four and six, and then be back in bed by six-fifteen.

He and Dixie agreed that most of the money he made would go for the trips he took with his softball team. The well-built Albright was one of the better players in the city’s senior slow-pitch softball league. He played for both a day team and a night team, and he was chosen as an outfielder for a local all-star team that went to the Senior World Series in Arizona. Albright, of course, was the league’s most colorful personality: He wore red shoes while everyone else wore black, and he twisted a coat hanger inside his cap so the cap would sit perfectly upon his head. He brought a cooler of soft drinks to every game for the other players to share. At the end of the game, there was nobody who could regale an audience with a funny story the way he could.

“No one ever saw Charlie upset—I literally mean that,” said a man who managed one of Charlie’s teams in the fall of 1990. “He went out of his way to try to be liked,” said a longtime friend who also played ball with him. “Every now and then there would be some jawboning during a game, maybe a scuffle between two players from opposing teams. But if somebody came after Charlie, he would back down, as if he was scared. He literally could not stand the idea of fighting. He would rather give you a present. Every time he saw one of my daughters, he gave her a gift or a ten-dollar bill.”

Because Albright’s former teammates were so fond of him, it is difficult even today for them to talk about a certain incident that took place a few months before the murders. Many of them still deny knowing anything about it; others say they have only heard about it secondhand. But at least two men have confirmed that Charlie Albright let his mask slip again.

At the end of one game, some players for the Richardson Greyhounds, Charlie’s day team, were sitting around the ballpark, shooting the breeze and eating some candy that Charlie had brought, when two women in a car drove slowly by. After the men joked that the women must be prostitutes, the team’s manager shouted, “Hey, Charlie, you’re single. Why don’t you take after them whores?”

Albright said, “Hell, I’d kill them if I could.”

Stunned the men turned toward their mild-mannered friend. On his face was a dark scowling look. “What do you mean?” the manager said, trying to keep the conversation light. “We’ve got to have whores. It keeps men from chasing married women.”

“The hell it does!” Albright snapped. Then he marched off to his car and left.

It was the first time anyone had ever seen Albright show any kind of anger. When the team assembled again for practice a few days later, the manager tried to apologize. “We were just shooting the bull,” he said.

“Well, that’s a touchy subject with me,” Albright replied. “My mother was a prostitute.”

He was not talking about Delle, he said, he was talking about his birth mother. The other men were speechless. Was this just one of Albright’s tall tales? In the months to come, a number of people tried to verify the story, including an FBI agent and a private investigator working for Albright’s defense attorney. They learned that while his biological father could not be traced, his biological mother was a nurse who had lived and died in Wichita Falls. Perhaps she never was the brilliant law student whom Delle Albright had described to her son. But there was no way they could determine if she had ever been a prostitute. Albright’s relatives, in fact, insisted that after a lengthy search through court records, Albright had been thrilled to find his biological mother. As an adult, he had visited her several times in Wichita Falls and had brought her gifts. He had even introduced her to Fred Albright and to his own daughter.

Yet somewhere in Albright’s mind, the connection between prostitution and motherhood had been made. It is possible that Charles Albright was wrestling with a very twisted version of the Madonna-whore complex, unconsciously seeking revenge on the mother figures who disappointed him by associating with prostitutes—the worst possible women he could find. On one hand he seemingly cared for prostitutes like Susan Peterson and Mary Pratt. He helped them financially, bought them dinner, and gave them presents. On the other hand, he wanted to punish them. Perhaps he hated what they had become. Perhaps he hated what he had become in their presence.

Whatever the reason, if Albright had truly decided the time had come to kill, he had put himself in a perfect position to do it. His paper route gave him an excuse to be out at night. He had prostitutes who trusted him enough to let him take them on a little trip. He had his parents’ old property just a ten-minute drive south of the Star, where, unseen, he could carry out the murders and mutilations. And because the property was in his father’s name, nothing could be traced back to him.

There was only one flaw in the plan—one Albright didn’t even know about. Charlie’s truck-driving tenant, Axton Schindler, had decided a few years back not to list his south Dallas address on his driver’s license. As he liked to say, he preferred to keep his privacy; he wanted the government to stay out of his business. Instead, he put down 1035 Eldorado, the address for Charles Albright.

“The police told me you had a number of true-crime books in your house,” I said.

“Oh, hell, there were other books—books of poetry, several Bibles, cookbooks, all kinds of books on art, watercolors, oils, and some books on science. It was as well-rounded a library as you wanted to find.”

“But in any of those murder books you read, did you learn why a serial killer acts the way he does?”

“Well, just for the sheer pleasure of killing a girl, I would imagine.”

“A serial killer,” I said, “would not have—”

“Would not have dumped them on the street where they would be easily found,” he quickly said. “Look, if I made up my mind I wanted to be one, I wouldn’t have been caught on the third killing. If I had decided to be a serial killer, I sure would have been a good one. You can ask anybody about anything I have ever done. I tried to be the best at what I did.”

March 22, 1991: Caught

Once word of Shirley Williams’ killing spread, the Star Motel turned into a ghost town. Some prostitutes, black and white, told officers John Matthews and Regina Smith that they were leaving Dallas. Others said they were getting out of the business. A few women, so desperate for drug money that they couldn’t leave, moved together to a street corner next to the home of a man who promised to serve as their lookout and bodyguard.

Cruising the area, Matthews and Smith spied a black prostitute, Brenda White, a seventeen-year veteran of the neighborhood. White tended to work alone on a street corner in front of a church, away from the other prostitutes. The officers decided to stop and make sure she knew about the murders. “Girl,” Smith said, “don’t you know there’s a killer loose? He’s now killing the black girls too.” “Well, I’m going to get my black ass out of here,” White replied. “I just had to mace a man who jumped bad on me the other night.”

White told the officers that a few days before, a trick in a dark station wagon had pulled up alongside her and that she had gotten inside the car. He was a husky-looking white man with salt-and-pepper hair, cowboy boots, and blue jeans. “Let’s go to a motel,” she told him. “No,” he said. “I’ve got a spot we can use.” As a way to protect herself, White never allowed a new trick to take her anywhere but a whore motel, so she told him to drop her off immediately. Suddenly, “a change came over his face,” she recalled. “It was like anger, rage. He said, ‘I hate whores! I’m going to kill all of you motherf—ing whores!’” Before he had a chance to grab her, White shot a stream of Mace into his face, threw open the door, and jumped out, breaking the heel of one of her favorite red leather pumps.

For the rest of the day, Matthews and Smith could not shake White’s story from their minds. They flipped through their notebooks. They thought about everything the whores had told them since the killings began. Always, they returned to Veronica Rodriguez’s rambling talk about being raped.

The next morning, as they were checking in for work at their police substation, Smith said, “We need to run a computer check on that Axton Schindler.” Because county government computers contain more information about citizens than city computers, she and Matthews drove to the Dallas County constable’s office near Jefferson Boulevard. There, a deputy constable on duty, Walter Cook, agreed to help them. Seated around the terminal, the officers asked Cook to type in Schindler’s address: 1035 Eldorado. The name Fred Albright popped up as the owner of the property.

Fred Albright? Where was Axton Schindler?

Cook punched in another code. It turned out that this Fred Albright also owned property on a street called Cotton Valley. Wasn’t Cotton Valley in the very neighborhood in south Dallas where the first two prostitutes were found? Cook kept typing. Fred Albright, the computer reported, was dead.

Matthews and Smith stared at the screen: The only clue in the case led them to a dead man. Then, after a pause, Cook said softly, “Maybe this has something to do with a man named Charles Albright.”

Several weeks before, Cook explained he had come to the office early one morning and had answered a call from a woman who would not identify herself. The woman had been friends with Mary Pratt, she said, and through Pratt had met a man whom she briefly dated. He was a very nice man, she said, but he had an odd love for eyes. She also happened to mention that he kept X-Acto blades in his attic. Cook asked for the man’s name. “Charles Albright,” she said.

If any other constable’s deputy had been helping Matthews and Smith that day, the link to Albright might never have been made. But good fortune prevailed. Cook typed in another code, and personal information for Charles Albright popped up on the screen: “Born—August 10, 1933. Address—1035 Eldorado.”

Somehow, they said, Schindler and Albright were connected. Perhaps Albright was Schindler’s “friend,” the one who had tried to kill Veronica Rodriguez. Their hearts racing, Matthews and Smith rushed to the county’s identification division and asked to see Albright’s criminal record. The officers discovered a string of thefts, burglaries, and forgeries and the charge of sexual intercourse with a child. The clerk then pulled out a mug shot of Albright, a photo of a rather handsome well-built man with grayish hair, angular features, and deep-set dark eyes—just like the man Brenda White had described. In the picture, Albright was frowning, his face perplexed, as if he was surprised he had been caught.

The clerk wondered why Smith was so excited. “Honey,” Smith said, “I think we’ve got the killer.”

On their way to the homicide department, Matthews and Smith rehearsed everything they wanted to say. They could not seem unprepared, Matthews insisted; it was nervy enough for two raw patrol officers to visit the legendary Westphalen and tell him they believed they had found the killer—although they had no solid evidence to prove it.

Westphalen greeted them politely. Matthews started, then Smith interrupted, and soon they were both talking at once. Westphalen sighed. “Calm down,” he said. “Let’s take it slow.” A few minutes later, after they had finished their presentation, Westphalen decided they were on to something. He put together a photo lineup of six mug shots and told Matthews and Smith to show it to Brenda White.

Immediately, Smith and Matthews tracked White down on her usual street corner and asked her if she recognized any of the men in the mug shots. White unhesitatingly pointed to Albright’s picture and said he was the man who had attacked her. A little while later, they showed the same lineup to Veronica Rodriguez. According to Matthews, when Rodriguez got to the third picture—Albright’s—she started trembling. Suddenly fearful, she refused to identify anyone. Matthews called Westphalen with the bad news. Rodriguez is so afraid of the killer, he said, that she won’t pick out his picture. “Bring her down here to see me,” Westphalen growled.

Westphalen knew if he could not get Rodriguez to break, he wouldn’t have the evidence to go after Charles Albright. Brenda White’s story offered only the prospect of a misdemeanor assault charge. But if Rodriguez identified Albright, the Dallas police could file charges for attempted murder, get a search warrant, and look through his house for evidence that might connect him to the three murders.

Smith and Matthews dragged Rodriguez downtown. In a small interrogation room, Westphalen stared with his icy blue eyes at the crack-addicted Rodriguez. Rodriguez began to shake again. Tears poured out of her eyes. She wouldn’t look at the pictures laid out before her. Trying to control his anger, Westphalen took a different tack. He told Rodriguez about the three girls, how they were brutally killed, how the police couldn’t get the killer off the street without her help. “This is so easy,” he said. “Pick out the picture of the guy who assaulted you, and we will get him and put him in jail, where he can’t hurt you.” Slowly, Rodriguez looked over the mug shots. While Westphalen and another officer watched, she reached for Albright’s photo, turned it over and signed her name.

At two-thirty in the morning on March 22, as a gentle rain fell on Oak Cliff, a team of tactical officers burst through the front door of 1035 Eldorado. Despite the home’s shabby exterior, the treasures of Charlie Albright’s eclectic life decorated room after room. One cabinet was filled with exotic champagne glasses, another held delicate expensive Lladro figurines of pretty young women. On one wall were Life magazine covers and valuable Marilyn Monroe movie posters.

As Charles Albright was handcuffed and led away, he never said a word. Stumbling out of bed in her nightgown, Dixie Austin looked incredulously at Albright and then back at the police. Unable to imagine what the man she loved could have done, she began to scream.

December 1991: Convicted

For a long time after Charles Albright’s arrest, most everyone involved in his case wondered whether the police had enough evidence to convict him of murder. Despite a withering all-night interrogation by Westphalen, Albright refused to confess to anything. He acted as if he had never heard the names of the murdered prostitutes. Police searched through every square inch of the south Dallas properties. They searched his Oak cliff house six times. The FBI even brought in a high-tech machine that could see through walls. Although the searches produced an array of interesting items—carpenters’ woodworking blades, X-Acto blades, a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, at least a dozen true-crime books—they never came up with the eyeballs. Behind Charlie’s hand-built fireplace mantel, police discovered a hidden compartment filled with pistols and rifles. None, however, turned out to be the murder weapon.

Nor could police find anyone who would admit to seeing Charlie with the three prostitutes on the nights they were killed. Dixie claimed that on the nights in question, Charlie did not leave the house early for his paper route and that he always came home on time. As the trial date arrived, Veronica Rodriguez decided to testify as a witness for the defense. She claimed that she and Albright had never been together and that Westphalen had coerced her into picking Albright’s photograph from the lineup. Axton Schindler continued to deny that he had saved Rodriguez from Albright. He said a Hispanic man named Joe had brought her to his door.

But Toby Shook, a low-key 33-year-old prosecutor working for the Dallas county district attorney’s office, had a trump card. For the first time in its history, the DA’s office was going for a murder conviction based solely on controversial hair evidence. Days after Albright’s arrest, the city’s forensic lab reported that hairs found on the bodies of the dead prostitutes were similar to hair samples taken from Albright’s head and pubic area. As evidence goes, hairs are not as conclusive as fingerprints—it’s impossible to tell how many other gray-haired men’s hairs might look similar to Albright’s hairs under a microscope—yet in this case, the lab kept running tests. Lab technicians said that hairs found on the blankets in the back of Albright’s pickup truck were similar to hair samples from the first two prostitutes killed, Mary Pratt and Susan Peterson. Hairs found in Albright’s vacuum cleaner matched the hair from the third prostitute killed, Shirley Williams.

An additional piece of the puzzle came from John Matthews and Regina Smith. The officers found a prostitute, Tina Connolly, who claimed that Albright was one of her regular afternoon customers on Fort Worth Boulevard. She never saw him cruise after dark, she said, except for one time—the night Shirley Williams disappeared. Connolly took Matthews and Smith to a secluded field near Fort Worth Boulevard where Albright used to take her for sex. There, they spotted a yellow raincoat, just like the one Williams was last seen wearing, and a blanket. Hairs on the coat and blanket matched Albright’s hair.

Albright’s defense attorney, Brad Lollar, tried to convince the jury that the case against Albright depended on the flimsiest circumstantial evidence. The killer, he said, was probably Axton Schindler, who just happened to skip town the week of the trial. Admittedly, the police had many unanswered questions about Schindler. Westphalen had spent hours interrogation him, trying to determine if he assisted Albright in the killings or was at least aware that Albright was murdering women on the rental property. But there was nothing to tie him to the case except for an empty .44-caliber bullet box found behind the house, which Albright might have dropped there himself. When Schindler’s and Albright’s photos were shown to dozens of prostitutes, none recognized Schindler, but many recognized Albright. Nor were there any hairs found on the dead prostitutes that could be linked to Schindler. Most important, no one who had ever met Axton Schindler could imagine he would have the slightest skill required to perfectly remove a set of human eyes.

Albright never testified. Throughout the trial, he sat quietly in his chair, his shoulders slumped, like a weak, humbled figure. Shook, in his closing argument, derisively called Albright “this former biology teacher, bullfighter, college ace, smart man who just can’t seem to have a job.” But Shook warned the jury not to underestimate Albright—that he had grown much smarter during this trial, that if he ever got out of jail, he wouldn’t make the same mistakes again.

On December 19, when the jury returned with a guilty verdict and a life sentence, Dixie collapsed in the courtroom. Albright’s friends avoided the reporters in the courthouse hallway; it was as if they did not want to be blamed for having lived with a vicious killer without recognizing him for what he was. But a stunned Brad Lollar, who genuinely thought he was going to get his client acquitted, strode tight-lipped out of the courtroom. “It’s always a miscarriage of justice,” he told the press, “when an innocent man is convicted.”

He was confident, he told me, that he would win his case on appeal. Another judge, he said, would see through the lies told at the first trial. He leaned forward in his chair and grinned optimistically. He couldn’t complain about prison life, he said. He was reading two books a week on the Civil War; he was taking notes for a book he wanted to write on the wives of Civil War generals. He was busy working as a carpenter in the prison woodworking shop, coaching the prison softball team, and writing letters to Dixie. He had just sent a request to Omni magazine for a back copy of its first issue because there was a painting on the cover that he liked. He grinned again and told terrifically funny stories about how crazy the other inmates acted. For a moment, it was hard for me to remember exactly what Charles Albright had been accused of doing.

But then I’d lock on the image of an eyeless young woman lying faceup on a neighborhood street. Why would such a kindly, lighthearted man want to cut out a prostitute’s eyes? Why was he so plagued by eyes, that potent and universal symbol, the windows to the soul? In the ancient myth, Oedipus tore out his own eyes after committing the transgression of sleeping with his mother. Did Charles Albright, a perverted Oedipus, tear out the eyes of women for committing the transgression of sleeping with men? Perhaps he removed their eyes out of some sudden need to show the world he could have been a great surgeon. Maybe he dumped that third body in front of the school to show his frustration over never having become a biology teacher. Or maybe a private demon had been lurking since his childhood, when the eyes were left off his little stuffed birds. Just as he long ago wanted to have a bagful of taxidermist’s eyes, maybe he decided to collect human eyes for himself.

“Oh, really, I have never touched an eyeball,” Albright declared again, for the first time becoming indignant with me. “I truly think—and this may sound farfetched—that the boys in the forensics lab cut out those eyes. I think the police said, ‘We want some sort of mutilation.’” Almost cheered by his reasoning, he returned to his psychologically impenetrable self. Whatever secrets he had would remain with him forever.