There was a Styrofoam wig head on Freddy Garcia’s desk. Judging from the half-dozen copper-colored gouges in its cranium, it had obviously been through the Wig Head Demonstration before. Nevertheless Garcia shook up a can of Krylon Interior/Exterior Enamel and aimed the nozzle at an untouched stretch of frontal lobe. The copper paint came out radiant, and immediately a metallic froth developed everywhere it had been sprayed. Each little Styrofoam cell twitched and disappeared, and when the paint had dried there was an inch-deep rift all the way down to the eye.

I bent down to inspect the damage more closely and the paint fumes flooded my nostrils. I can’t say it was a entirely unpleasant smell: I even thought I could detect, mixed in there with the solvents and propellants and halogenated hydrocarbons, the faintest breath of anise.

Garcia looked down at the wig head, at its lustrous new imperfection.

“It’s a scare tactic,” he admitted. “Some kids are onto it. They see the wig head demonstration and they come up and say, ‘Hey man, I don’t spray that stuff right on my brain, man!’ But others, you know, they’ll start thinking. I mean if it does that to that Styrofoam, imagine what it can do to your tissues and lungs.”

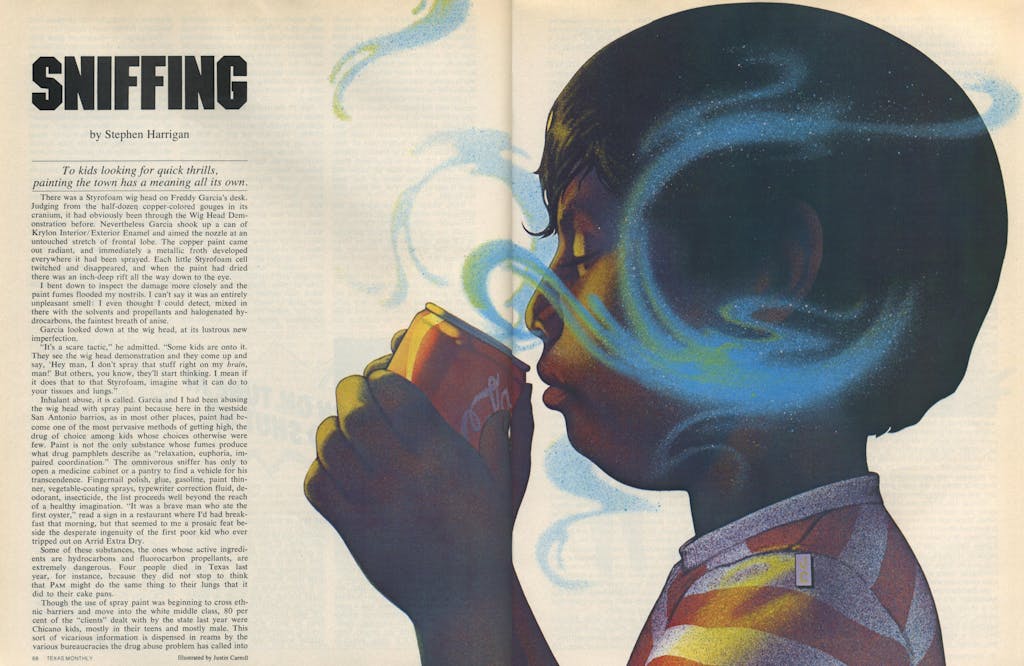

Inhalant abuse, it is called. Garcia and I had been abusing the wig head with spray paint because here in the westside San Antonio barrios, as in most other places, paint had become one of the most pervasive methods of getting high, the drug of choice among kids whose choices otherwise were few. Paint is not the only substance whose fumes produce what drug pamphlets describe as “relaxation, euphoria, impaired coordination.” The omnivorous sniffer has only to open a medicine cabinet or a pantry to find a vehicle for his transcendence. Fingernail polish, glue, gasoline, paint thinner, vegetable-coating sprays, typewriter correction fluid, deodorant, insecticide, the list proceeds well beyond the reach of a healthy imagination. “It was a brave man who ate the first oyster,” read a sign in a restaurant where I’d had breakfast that morning, but that seemed to me a prosaic feat beside the desperate ingenuity of the first poor kid who ever tripped out on Arrid Extra Dry.

Some of these substances, the ones whose active ingredients are hydrocarbons and fluorocarbon propellants, are extremely dangerous. Four people died in Texas last year, for instance, because they did not stop to think that PAM might do the same thing to their lungs that it did to their cake pans.

Though the use of spray paint was beginning to cross ethnic barriers and move into the white middle class, 80 percent of the “clients” dealt with by the state last year were Chicano kids, mostly in their teens and mostly male. This sort of vicarious information is dispensed in reams by the various bureaucracies the drug abuse problem has called into being. For several weeks I had been gathering it, reading technical reports and flyers with skulls and crossbones superimposed on them and thumbing through guidebooks on State of Texas drug lore (“Is it illegal to water-ski under the influence of drugs?”). I had atteneded a regional meeting of the National Youth Project Using Motorbikes (NYPUM, as in NYPUM in the bud) where I had watched movies of kids puttering around on minibikes to keep their minds off sniffing. Several times I had visited the offices of SPODA, the State Program on Drug Abuse, and sat in a room whose floors were stacked with printouts and surveys and reports. A woman had sat behind her desk and called out late-breaking statistics that she read from the dial of what looked like a desk calculator.

But here in San Antonio I was after “observable data.” I was in the offices of the Toxicant Inhalant and Drug Abuse Prevention Program (TIDAPP), a project of the Mexican American Neighborhood Civic Organization (yes, MANCO). I had long ago given up trying to understand just which acronym I was dealing with at any given moment—they seemed to fit together anyway, like those kitchen canisters that come stored inside one another. Municipal programs were partially funded by state programs, state programs were partially funded by federal programs, etc. It was a world of clever acronyms and litanies—youth referral, youth outreach, youth advocacy—a world suspended within webs of matching grants and grant proposals and the ghosts of de-funded programs.

Garcia and Juan Pacheco, who had joined us, both worked for TIDAPP, Pacheco as supervisor of the project and Garcia as one of four caseworkers. They were in their late twenties and had grown up in the westside during the days when glue sniffing had been epidemic. (Now it presented fewer problems, in part because of a mustard-seed additive introduced by manufacturers to make would-be sniffers nauseous.)

“Mainly what we do here is work with parents and kids,” Pacheco explained. He had a round, rather wistful face; a full beard seemed to make no impression on it. “Our project is a prevention project. Some of these kids—they’re so messed up they want to continue sniffing. They don’t care if they become vegetables or not. But we’re after the ones we can help. You develop the leaders first. You go to some guy you know is a leader, he’ll tell his friends, ‘Hey man, that stuff’ll kill you!’”

“Who knows what ‘prevention’ is?” Garcia conceded. He was sitting on a table, throwing a pencil up in the air. There was a certain gringo affability in his voice, but his appearance carried hints, I thought, of militancy: he wore his hair as straight and symmetrical as an Apache’s, and there was an isolated unshaven spot beneath his lower lip.

“Actually what we mean by prevention,” he went on, “is to produce some unconscious response in them—something that tells them at the right time, ‘Hey, wait a minute—that guy said something about not doing this.’”

Though the deleterious effects of sniffing paint have been, as in the case of other drugs, hysterically exaggerated at times, there are still very good reasons not to mess with it. It may not directly corrode the brain or noodle-ize the bones, but there is evidence that chronic use can cause liver and kidney damage, and that large doses, in combination with exertion or shock, can produce cardiac arrhythmia, which can lead to death, and has. A number of sniffers have suffocated after losing consciousness with a paint-filled plastic bag over their nose and mouth.

As for the high that sniffing paint induces, I had no direct knowledge and no plans to obtain any. I understood paint to be a cheap, giggly sort of high, awash with all-purpose euphoria, capable of conjuring up maudlin hallucinations and aggressive behavior. Last week, Pacheco mentioned, Woolco had run a special—three cans for a dollar—and three cans was enough to keep what TIDAPP identified as a “moderate” sniffer high for a week. There was a city ordinance against selling paint to minors, but it was rarely enforced and easy enough to get around anyway: kids just found a wino who would buy their paint for them in exchange for 50 cents.

I spent the rest of that morning perusing the TIDAPP traveling display, for which the wig head was the centerpiece, and watching a crude slide-show cartoon about a Chicano Everyboy named Juanito who, unwilling to stay home because of an alcoholic father who regularly beats him, wanders the streets until he encounters a grinning little totem with a nozzle on his head named “Spray-O.” “I make kids sick!” Spray-O boasts, and of course Juanito falls under his tutelage, begins to sniff (“My son,” his mother cries, “why do you smell that stuff?”), gets hit by a car, sees Death, recovers, reforms.

Another slide tray featured reenactments by TIDAPP graduates of how paint is consumed. Here in San Antonio the practice was to spray the paint into an empty Coke or 7-Up can and inhale it from there, rather than breathing it from a plastic bread bag or a soaked rag. The advantages were obvious: not only was the suffocation problem solved, but also the sniffer could walk down the street while pursuing his hobby, leaving the police or other interested parties to assume he just had a funny way of sipping a Coke.

There were more slides, of camp-outs, basketball games, concilio meetings between parents and TIDAPP workers. When we had seen them all I went out with Pacheco and Jesse Chagoya, another TIDAPP worker, for a tour of the neighborhood. TIDAPP operated in four main areas, two of them on the westside and all but one composed largely of housing projects.

Every few minutes, as we drove along, Pacheco would announce that we were in some new area—Mirasol, say, or Alazan Apache—but the borders we had passed through to reach them were invisible to me. The main arteries were a long pastel wash of bars and panaderías, of meat packers and Spanish drive-in movies. It was a cultural continuum broken only rarely by an intrusive Pizza Inn or Dairy Queen, grafts from another world that the living tissue of the barrio seemed to accept tentatively at best. The westside imparted that sort of cultural integrity and was vast enough to suggest, in itself, a foreign country. It had the air of a Mexican border town that had suddenly lost its tourist trade and was beginning to recede into its own legitimate heritage. The vibrancy managed to survive even in the residential neighborhoods, where what little ethnic gloss there was was overwhelmed by drabness. We passed one housing project after another; each to me was identical and gave off a grim sense of déjà vu that reminded me of Indiana turnpike stops. All the projects seemed to have the same 400 or 500 units, the same rusting patio furniture, the same graffiti scrawled in gold or silver or copper spray paint on the walls. (These colors, more potent and aromatic than nonmetallic paints, were virtually the only ones that westside sniffers used.) Pacheco pointed out one of these units as his home, the place where he had been born and raised, and as we cruised through the neighborhood I watched the abbreviated, almost imperceptible signals he gave to the kids who were hanging out by the project. It was a kind of code—it involved maybe a faint raising of the eyebrows, a conspiratorial smirk, a certain cool cast to the face that implied empathy and tolerance and that seemed to me to instantly allay concern about the strange gringo in the van who was writing down things in a notebook.

When Pacheco was growing up here there had been gang wars, and he reminisced about how, when driving down this street at night, he had had to flash his lights, a code that demonstrated he was not from enemy territory.

“With gangs around, all the anxieties were directed outward,” he said. “Now it’s different. People go into themselves more. I think that’s why we have so many sniffers.”

Chagoya parked the van near a concrete culvert that seemed to stretch for several miles in either direction. We all got out and began to inch down a steep grade that led to one of the tunnels. I had heard of the tunnels before, that there were dozens of them in the city, that taken altogether they ran for hundreds of miles, and that each one was several miles long and wide enough to drive a car through. They were used for storm drainage, but they were also a system of catacombs marvelously suited to every form of criminal endeavor: dank, spooky, laced with smaller tunnels that could be used as escape routes should the police find the nerve to pursue anyone through them.

When we reached the entrance of our tunnel I could see that it was illuminated about every hundred feet or so by shafts of light that came from the smaller drainage tributaries. By that light we could see perhaps a half-mile of a corridor that ran all the ay to Concepción Park on the other side of town. I had a brief, apocalyptic image of the Alamo, of La Villita and Hemis-Fair Plaza, of every prim, quaint, well-tended structure in San Antonio suddenly plummeting through their foundations and landing in these nasty vaults that latticed the city.

There were no sniffers down the corridor—had there been, they had probably long since heard our echoes and scurried out one of the side tunnels. There was a fetid smell emanating from the inch-deep water that was seeping into our shoes. Names of sniffers were written on the walls in florid, oversized script. In the half-light these names looked like pictographs, and I felt like an archeologist on the trail of an unknown civilization.

Pacheco’s shoes had slick soles and he was having a hard time keeping his footing. “Kids play hooky here in the daytime. They go down to HEB and steal some potato chips or something and then come hide out in the tunnels all day and sniff paint.

“When we first started coming over here they thought we were undercover cops. We used to come through on motorcycles form Concepción Park and chase them all the way down. We’d have guys waiting at the entrance to catch them. Then we’d talk to them and try to get them involved in the program.”

On the way back out of the tunnel I noticed a few empty Coke cans, and there was a puzzling postscript to some of the graffiti on the walls—the notation c/s. Later I found out that this was an abbreviation for con safos, which meant that the name after which it had been written could not be defamed, not even if someone came later and wrote joto or some other slur beneath it. The name stood as it was written, inviolate.

When we left the tunnels we headed for a vacant lot where a good deal of sniffing had reportedly been taking place lately. On the way we picked up a boy named Eduardo, a fourteen-year-old who billed himself as a reformed sniffer but about whom, Pacheco admitted later, he still had his doubts.

When Eduardo climbed into the van Pacheco explained to him in Spanish what I was doing, and although I couldn’t quite follow the conversation I was able to assess well enough the tone that Pacheco brought to it: a concern so easy and authentic it seemed far removed from the bureaucratic grantsmanship, the paneled offices and Selectric typewriters of the organization he represented.

I tried to emulate this tone when I asked Eduardo a few routine questions about his paint-sniffing career. He was nervous, chewing on a pop-top and periodically taking it out of his mouth and inspecting it, as though he were an artisan fashioning a piece of jewelry with his teeth. There was a Rimbaud look to him, some sediment of innocence that was constantly being stirred up. He answered my questions in imperfect, staccato English.

“This friend Armando,” he said, “he was sniffin’ and he went to that half-way house and he saw how all the sniffers were—skinny, you know, and you could see their brains—not their brains, their skulls—and he came home and was pretty scared you know. So I don’t do it anymore.”

“This area we’re going to,” Pacheco said as we drove off, “is totally isolated. There’s nobody working in there. We’ve been trying to make some contacts but it’s pretty slow at first.”

I realized that in this business of making contacts a suspicious-looking gringo could only be excess baggage, but since nobody else seemed to worry about it I didn’t either. We came to a part of the westside where the trappings of Mexican culture simply gave out in the face of utter poverty. We tramped through an overgrown vacant lot with Eduardo leading the way like a hunting dog, even letting out a factious howl when he reached a clearing circumscribed by empty soft-drink cans.

We were on their trail. I picked up a 7-Up can and gingerly put my nose to it. No anise there. This sniffer had been using some other flavor. There was a pebble in the bottom of the can, in imitation of the little ball that keeps paint stirred up in spray cans.

Eduardo began stomping cans under his foot. There was a manic, self-righteous gleam in his eyes.

“That’s so they can’t use them again,” Pacheco explained. He picked up a Budweiser can. There were screwdriver holes punched in its bottom.

“Good to the last sniff, huh?”

Holes had been punched in the spray cans as well. There was an old car seat on the other side of the clearing.

“Boy, these kids thought of everything,” Pacheco said. “All the comforts.”

I made several more visits to San Antonio during the next week but my prey continued to elude me. One morning I rode with Juan through the housing projects and into a neighborhood of prim little houses with pastel picket fences and plaster statuary scattered about the yards. At one of these houses he stopped and honked his horn, startling a wino in a fur hat. When no one came to the door he got out of the car and yelled up and down the street the name of the kid he was looking for.

“I thought he might be home today,” he said. “They tend not to go to school on Monday. They like to take a long weekend. This kid we’re looking for has been through a lot. He just got out of Gatesville. His mother doesn’t give a shit about him, either. I think there’s maybe thirteen in his family. The majority of kids we get—I’d say about eighty per cent of them—are from one-parent families, the father’s gone off somewhere. To distribute the love and affection all these kids need is hard because there’s so many of them. Probably what they do is ignore all of them.”

Later that day I went out with Garcia on the same errand. Several times he pointed to some teenager leaning against a housing project dumpster, staring sullenly at me as we drove by. “That guy there’s a sniffer. Only I don’t know him too well. He wouldn’t talk to you anyway.”

Once or twice we saw kids sitting on the sidewalks holding Coke and 7-Up cans under their noses, not even bothering to go through the pantomime of sipping. They would eye us suspiciously, ready to break and run if our car should slow down.

Finally I hit upon the simple expedient of bribery. Garcia said he was sure he could find a few sniffers who would be willing to talk in exchange for a small “honorarium,” though he was concerned they might spend the money on paint. We decided to keep the cash minimal and take the kids to dinner.

Since Garcia needed a few days to set this up I returned to Austin, where Jesse Flores, director of the Youth Advocacy Program there, had arranged a sort of symposium with about ten of his former sniffers, eight boys and two girls. Several of the kids, in an effort I think to put me at ease, said they admired my tennis shoes. They said I could go anywhere in the eastside and be accepted because I wore Converse All Stars. But several times during the discussion I think I blew this advantage, as when a kid told me how, on paint, he had “ripped off a house.”

“What? You ripped off a whole house?”

“No man, no a whole house! I ripped off the stuff in the house!”

A small boy of about fourteen with a look of beatific self-reliance told me a story so plaintive and lovely it reminded me of Huckleberry Finn. He used to get high on paint, all by himself, then sneak out of his house, away from his alcoholic father and nagging mother, and break into a house several blocks away whose inhabitants were apparently on vacation. All alone in this house he would sniff paint, watch TV, sleep in the bed, wake up sometimes unable to remember where he was, but unconcerned enough about it to make himself some breakfast.

When I got back to San Antonio I had a talk with Rogelio Chapa, the executive director of MANCO, who had once been a heroin addict and had served time for manslaughter after accidentally killing a man in a bar fight. Chapa was unsure about my writing about these details of his past—he was afraid they would convince kids that his being a junkie had been a necessary prelude to his current success. But he was, you could sense it, an extraordinary person, and his lifelong ordeal had not yet been flushed from his face. Otherwise he was trim and middle-aged: he could have been an actor on one of those Spanish soap operas Pacheco had told me the barrio grandmothers stayed home all day to watch. He had a scar on the far left side of his face, and his half-frame glasses coordinated nicely with a thin mustache. He was talking about something he called the “continuous variant activity approach.”

“These kids, their attention span is very short—they’re prone to get bored very quickly and if you don’t have something for them right away they’ll run off to their stash and start sniffing paint again. We’ll have a basketball game, say, then once they start messing around, goosing each other in the ass, we say, ‘OK!—a pool tournament!”

“What we need is a center with enough stuff where we could keep prolonging what we call their ‘abstinence span.’ You’ve just got to keep them busy. It’s going to take community involvement to solve this problem. Parents are going to have to take control of their youngsters. There are some mothers who are afraid of their twelve-year-old offspring because they become violent on paint and attack them with bottles and broomsticks.

“These kids don’t sleep properly, they don’t eat properly. They become aggressive, violent, get into fights at school. They’re responsible for a lot of the vandalism around here. This hasn’t been documented by the police, but we know these youngsters, we know what they’re up to. The only recourse is for guys like Juan and Freddy to get out there and do some street-level counseling. It’s a very unstructured kind of preventive approach we have with them.”

Chapa reminisced for a while about the forties and fifties when the westside had been San Antonio’s main source of drugs. He said that various well-positioned and respected Anglos would come to his house and he would score for them.

“The thing that was most prominent then was grass. But then when heroin came in you’d see the change. Guys who used to go around with fine Stetson hats and fine straight-legged pants and used to drive big cars were suddenly walking along the street dressed like bums.

“You get a youngster today sniffing paint—I’ll cut my own throat if his grandfather wasn’t into dope here back in the forties.”

Garcia had found three sniffers for me. One of them was a thirteen-year-old girl that Virginia Tijerina, TIDAPP’s only female caseworker, had been working with for about three months. Tijerina didn’t want her to fall under the influence of the other two kids Garcia had brought, so I talked to her alone in Tijerina’s office.

She was a very shy girl, whom I’ll call Louisa. Her father was in state prison, her mother was an alcoholic. For three and a half years she had been sniffing paint—she said she always sniffed “Bright Silver”—and not going to school. Once, after running away from home, she had been sent to Villarosa, the halfway house where Eduardo’s friend had seen the chronic sniffers and resolved never to have anything to do with paint again. Louisa said she had never lost weight like the other “spray kids.” Though she would sometimes sniff paint all day and all night she had always retained her appetite. After a month or so in Villarosa she had run away, made a truce with her mother, whose authority she had previously not been able to abide, and moved back home.

It was an awkward interview. Louisa spent the better part of it looking down at her knees, and my attempts to isolate her paint-sniffing experience—one single thread from an intricate tapestry—seemed less and less to the point.

“What do you do now? What do you do all day?”

“I stay at home. I watch the Mike Douglas Show. Sometimes I fell like walking and I go for a walk.”

“There’s no way I can convince her to go back to school,” Tijerina told me afterward. “She doesn’t care about her life.”

The two boys Garcia had found for me were both about seventeen, both in high school. One of them—Alfredo—readily admitted that he still sniffed. He said this with an exasperated smirk, as though he were truly impatient with himself.

Raul, the other one, had been a heavy sniffer but claimed he was reformed now. His hair was shorter than Alfredo’s and he obviously paid more attention to it. He had been in and out of reform schools and homes for boys for a good deal of his adolescence and he had that wiriness, that skittish grace that people who are accustomed to making their own way so often seem to have. At seventeen, he radiated for the adults in the room a patronizing, recalcitrant courtesy. He was wild and he knew it.

Garcia had told me earlier of a common paint-induced hallucination, one that several kids had told him about during one of those long evenings when he had taken them camping.

“They’d see weird things. Like toy soldiers in a field. Then, of course, the train—a lot of them saw that. I think the train more or less depicted death for them. Of course the power of suggestion had something to do with it. Not everybody saw the same train, but they did see death in some form or fashion.”

I asked Alfredo if he had ever seen the train.

“No, but como, I would think I was in the sky. In the tunnels once I thought, you know, I did it too much—I started seeing things like monsters and started running. If you’re somewhere alone, though, you get everything out of your mind and you do the spray, then you’re happy.”

Alfredo said he had tried paint for the first time in the tunnels at the insistence of his friends.

“They told me to pick up an empty can, you know, then they handed me a spray can. They said, ‘Spray this in there!’ I said, ‘No.’ I heard it was bad for you. But then I tried it, I did the spray. When I did it the first time it tasted ugly. Then I started doing it and liking it, and they said, ‘It tastes good,’ and I said, ‘Yeah!’

“Now sometimes I do it, sometimes I don’t. When I don’t have anything to do I go out with my friends. If I see Juan and Freddy comin’ I throw it away.

“I do it cause there’s nothin’ else to do. Sometimes when I go to school they smell the spray and call me spray-head and everything. But other guys, they have stuff to do—they play basketball and football and everything. I don’t like to play those. I like to swim, but there’s no pool here.”

I asked Raul what paint was like.

“It’s like—you have a feeling of dizzy—a buzzing to your ears. Once I see a shadow, I see death. I was like this, doin’ the spry”—here he crouched down on one knee and put his head beneath his nose—“I was like this and I had a feelin’ this man was comin’ back on me. I see he had a—what do you call it?—sickle. He told me to name my favorite station on the radio. Then he hit me like this on the shoulder”—Raul rolled from his position as though something powerful had just swooped by and grazed him. “Then he ran away. When you do spray you have a feelin’ someone’s comin’ back on you but you can’t see him.”

Another time, he said, he was high on paint, and God and the devil both appeared to him in his room.

“Good said, ‘You want to come with me, Raul, or with him?’ I went with God. I smashed the can.” He pulled a rosary out of his pocket and displayed it.

Raul also showed us a long scar on his forearm where a friend had cut him with a knife once when they were both high on paint. He said he didn’t fell a thing when it happened.

I asked him why he had ever enjoyed sniffing paint.

“I just have fun,” he said. “I see the basketball guys playing. It’s bad for you though. You can get your brain skinny.”

Afterwards we all went out to dinner at a Mexican restaurant. We all had a number two combination plate. Freddy Garcia got heartburn.

“I always get heartburn when I eat Mexican food,” he said.

We talked about the tunnels and about mothers who believed their kids sniffed paint because they had the evil eye, who would consult readers and spiritual advisers and sometimes even chain their children to the bed to keep them from sniffing.

Pacheco mentioned that it looked as if TIDAPP may have run its course, that the program may not be refunded for next year.

“During the three years we’ve been here some guys have made it,” he said. “You don’t always hear about the results until years later when you get an invitation to their graduation or wedding. That makes you feel pretty good.”

On the way back to the MANCO offices we dropped the two boys off at their housing projects. When Raul got out he offered me a three-stage handshake and said, “When will I see you again?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I watched him walk back to the housing project. There was a full moon and by its light the silver paint on the walls was almost luminous, so that I could make out each signature and, below the, each c/s, the charm that guaranteed power over one’s own name.

- More About:

- Health

- Longreads

- Crime

- San Antonio