Billy Scroggins drove out of Abilene, where he’d been working on a maintenance job, and headed toward Levelland, a small town thirty miles outside Lubbock. It was Friday afternoon on March 6, and he was eager to meet his wife, B’Anna, at the regional boys’ high school basketball tournament. Their hometown Vega Longhorns were playing at 6:30 that evening.

Vega fans were still riding the wave after their team upset number fifteen Floydada in the 2A regional quarterfinals at West Texas A&M University earlier that week. Carson Kirkland, a senior, had scored 37 points for the Longhorns, helping them advance to the semifinals for the first time since 2012. “Playing in Levelland has been all of our dreams since we were little,” Kirkland told Amarillo’s KAMR-TV after the game. “I think it’s definitely going to be a different atmosphere.”

Billy and B’Anna’s favorite pastime was taking their son and daughter—now 22 and 16 years old—hundreds of miles to Dallas or Oklahoma City to watch professional sports. They’d also gone to every high school basketball and football game in Vega. It was a three-hour drive from Abilene to the Texan Dome in Levelland, but Billy hadn’t given it a second thought: there was no way they were going to miss the basketball tournament.

Two days earlier, Texas had reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19. But public officials had not yet taken serious action to slow its spread. That week President Donald Trump called the virus “very mild.” At a press conference in Austin the day before the tournament started, Governor Greg Abbott said that “the risk to Texans remains low.”

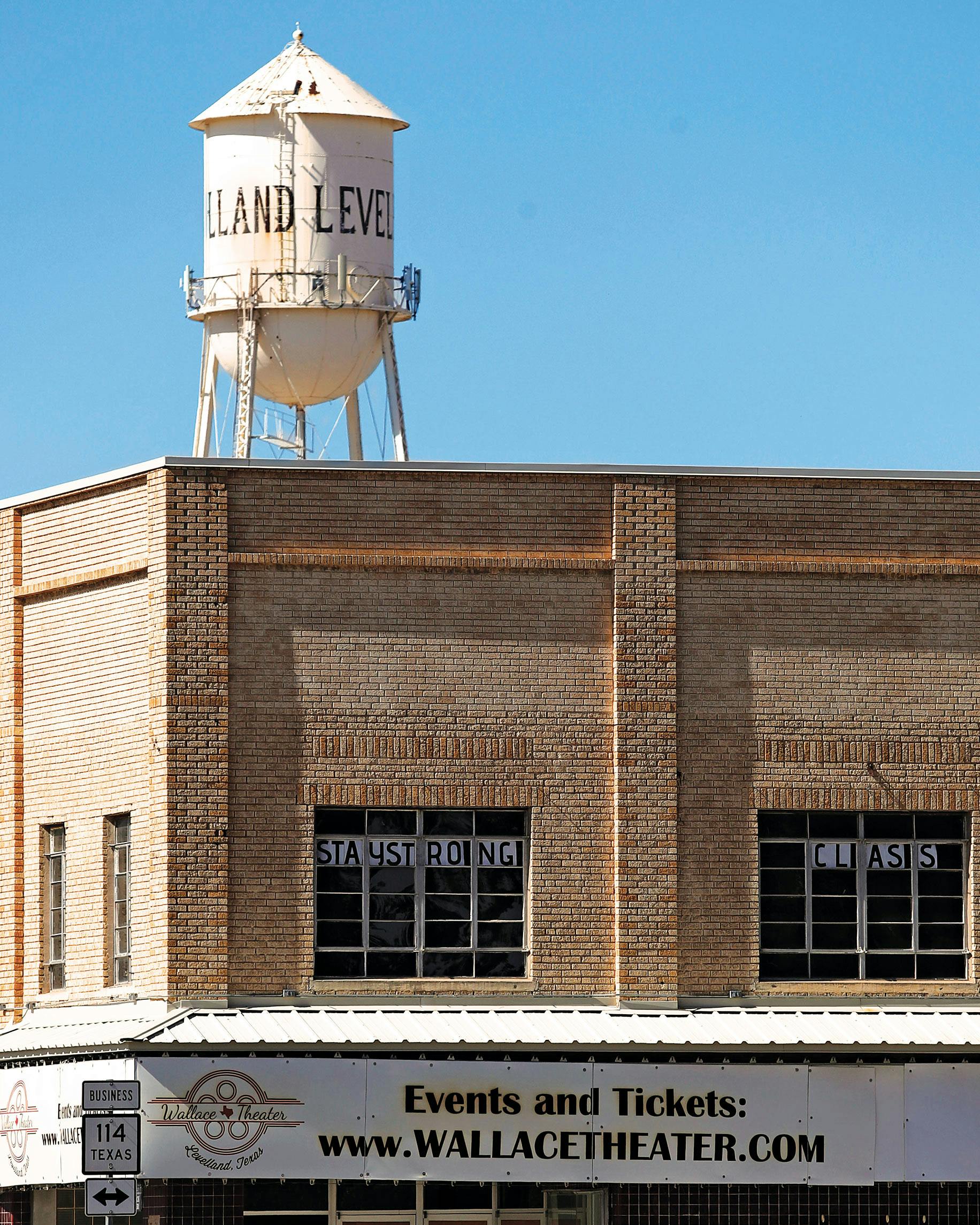

Basketball is king this time of year in the rural communities of the Texas Panhandle and South Plains, and nearly two thousand people attended each of the tournament’s three sessions, with six games slated across two days. The winners of the tournament’s two brackets would advance to the state semifinals. Billy made it before the Vega game tip-off, and the Scrogginses watched their team fall behind early and fail to catch the Sundown Roughnecks, losing 69–58.

Other teams also drew spirited crowds. School bus driver Ralph Albracht, who is 78, traveled eighty miles from his farm in Nazareth, population 297, to watch the Swifts beat O’Donnell. A regional powerhouse, Nazareth’s boys’ and girls’ basketball teams have won a combined 29 state titles (the girls won twenty-three of those and were already on their way to a twenty-fourth).

Sixty-year-old Michael Dominguez had no particular allegiance to any of the teams playing in the tournament, but he hadn’t missed the event in years. He lives nearby, on a corner lot in Levelland. Ever since his two daughters got jobs for the company that operated the concessions at the Texan Dome, he’d come and stop by one of the stands to order a Frito pie—always a Frito pie—before settling down in his seat.

After the games ended, Dominguez, Albracht, and the Scrogginses returned to their homes in Levelland, Nazareth, and Vega—three dots on a map along a 120-mile stretch of U.S. 385—all looking forward to the future. Dominguez, who had spent a month at home recovering from knee surgery, was excited to return to his job in the garden department at Walmart. Albracht was eager to drive Monday’s 22-mile school bus route, a job that had kept him busy in his post-retirement life.

And Billy and B’Anna Scroggins, 44 and 39 years old, inched ever closer to the birth of their first grandchild. At the gender reveal party in October, their son, the father-to-be, shot a balloon basketball at a hoop in the driveway. They watched as it exploded against the backboard in a cloud of blue dye. They were going to have a baby boy. Then, a few months later, a new ultrasound revealed they were actually having a girl. B’Anna spent most of her free time planning for the baby, helping her son and his fiancée prepare their nursery. She was excited to be a grandmother—it was just about all she talked about. The baby’s due date was only two months away.

On the nightly news after the tournament’s exciting first day, the NBC affiliate in Lubbock played highlights: a last-second three-pointer that sealed a win for New Home; Nazareth staving off a determined O’Donnell team; fans cheering happily in the stands. In another segment, news anchors read a brief report dispelling rumors circulating on social media that a case of COVID-19 had popped up in Lubbock and warned of scammers targeting people affected by the coronavirus. Only 164 cases had been reported nationwide. “Health officials say the risk is still low for most Americans,” the anchor said, before turning to the weather forecast.

At that point, COVID-19 was little more than an afterthought for many rural Texans. It was still a far-away virus that mostly affected distant countries or cities where people practically lived on top of one another. How could it spread in the vast, empty plains? No one anticipated that the virus would turn a normal, innocent event like the Levelland basketball tournament, so deeply woven into the cultural fabric of the region, into the catalyst for an outbreak that spanned at least four rural counties and left three people dead.

According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, at least seven people who tested positive for COVID-19 in March attended the tournament in Levelland. But when reached for comment in April, DSHS spokesperson Lara Anton said investigators were too busy tracing more recent cases to provide any more information on cases that may have been linked to the tournament. “There is no way to know from whom the transmission occurred or precisely when transmission occurred,” she added.

Tournament director Bart Bradshaw had taken extra precautions, after growing concerned by news reports from around the world—international attention had been focused on Italy that week. He made sure all of the handrails and door handles were wiped down, and the restrooms and ticketing areas disinfected, before and after both blocks of games Friday, then again before the championship round Saturday. “We had done everything possible to keep everyone as safe as possible during our tournaments with the knowledge we had at the time,” he said later.

B’Anna Scroggins began to feel sick the week after the tournament. She had gone to the gym and to work that Monday, but she felt tired and thought she was running a fever. The next day, her temperature rose to 101 degrees, and the day after that her head began to ache badly. Then, on Thursday, she couldn’t get out of bed. She went to the doctor, where she was tested for strep throat, and was told to alternate between taking Ibuprofen and Tylenol.

On Saturday, March 14, Billy took B’Anna to a free-standing emergency room in Amarillo. She received a chest X-ray, which showed she had pneumonia, and tested positive for the flu. Her oxygen level was low, and she struggled to breathe.

Billy could tell the nurses were worried. The doctor told him to take B’Anna to BSA Hospital in Amarillo, one of the city’s major health-care centers, where a room was waiting for them on the sixth floor. Doctors there treated her with antibiotics, but on Tuesday, March 17, two days after the first death related to the coronavirus was reported in Texas, B’Anna was moved to an intensive care unit at BSA. She was sedated, intubated, and placed on a ventilator. Doctors diagnosed her with acute respiratory distress syndrome and gave her a test for coronavirus.

Billy wasn’t allowed in his wife’s room, but he stayed at the hospital anyway, watching her helplessly through the glass door. The doctors told him they thought B’Anna had a chance to make it if she survived through Sunday. The results of her coronavirus test came back Thursday: she was positive.

OOn Friday, March 13, nearly a week after the basketball tournament ended and the day Governor Greg Abbott declared a state of disaster, one of Michael Dominguez’s daughters came to see him at his Levelland home. He had chills and a slight cough that he couldn’t seem to shake. He went to see his primary care physician, who noticed that Michael had a low-grade fever, a cough, and a slightly runny nose. He tested negative for the flu, was prescribed antibiotics, and went home.

But his symptoms worsened over the weekend. At 2 p.m. on Monday, Michael texted his daughter Liz that he had decided not to return to work, as he’d planned for a month, because he was now feeling dizzy. When Liz called, he sounded as though he was having a hard time breathing. Her son tried to persuade his grandfather to go to the emergency room. “It’s okay,” Michael said. “It’s probably just a cold.” The coronavirus was the last thing on their minds.

The next morning—while most of the country was debating whether to go out to bars to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day—Michael was taken by ambulance to Covenant Medical Center in Lubbock, where he was tested for COVID-19. When Michael spoke to Liz at 6:30 that evening, he was struggling to breathe. “Okay, Dad, I love you,” Liz told him, not wanting her father to expend too much energy by speaking. “I’ll talk to you tomorrow.” But she didn’t get the chance.

Michael tested positive for COVID-19 the next day. Hospital staff sedated and intubated him and hooked him up to a ventilator to help him breathe. Liz was shocked. Her father had been home from work for the past month, recovering from his surgery. He’d hardly left the house. There was only one place she could think of where he could have contracted the virus: the regional basketball tournament in Levelland.

Other attendees were also starting to feel unwell. Eighty-four-year old Catherine Huseman, who was famous in Nazareth for the cinnamon rolls she baked for the Swifts, began coughing a few days later and was hospitalized on March 19. “It all hit pretty fast, once it got started,” her son, Derwin, later said.

Ralph Albracht had begun to cough upon returning home from San Antonio, where he’d watched the Nazareth team lose in the state semifinals at the Alamodome on March 12, hours before the entire tournament was suspended over coronavirus concerns. Albracht’s doctor suspected that he had pneumonia and sent him to the same Amarillo hospital where Huseman would end up days later.

A nasal coronavirus test came back positive. Albracht knew that his advanced age put him at a higher risk for dying from COVID-19. As doctors sedated him to put him on a ventilator, he wasn’t sure whether he’d wake up.

Within a month following the Levelland tournament, the coronavirus had taken hold in communities all over Texas. On March 17, when B’Anna was moved to intensive care, 19 of the state’s 254 counties had reported confirmed cases of COVID-19; by April 2, more than half had.

Though B’Anna had made it through the week under sedation at BSA Hospital in Amarillo, she was getting progressively worse each day. By now the hospital was allowing Billy to be in the same room as his wife. But staff told him it was still too risky for him to come and go from B’Anna’s room as he pleased, so he’d change into a hospital gown and mask and stay next to her for eight hours straight, not leaving her side even to get food or go to the bathroom, before returning home at night to sleep. Billy held her hand and spoke softly to her, though she was heavily sedated and couldn’t respond. When their children talked to her through the phone, Billy saw tears in B’Anna’s eyes.

Meanwhile, he subsisted entirely on packages of beef jerky and almonds. His pants no longer fit—he’d lost twelve pounds. He was beginning to feel ill too. He thought it was from the stress.

Then, on March 23, Billy could make it only about seven hours with B’Anna. He was too tired and felt weak. He went home and slept for a few hours but was awakened at 2 a.m. by his ringing phone. B’Anna’s doctor said her heart had stopped. She was dead.

As he faced his first few days without his wife of 23 years, Billy continued to feel tired and weak. If he had the virus, Billy thought, he had a good chance of dying because of his severe asthma. The week before B’Anna’s funeral, while he was waiting in the emergency room to get tested, Billy said a prayer. “I didn’t ever think that God would take both parents,” he said later. “I said my prayer and left it up to God. I told him, ‘There’s no way.’ ”

O

ne hundred and twenty miles away, at the Covenant Medical Center in Lubbock, Michael Dominguez was fighting for his life.

Liz couldn’t visit him: she was self-quarantined in the bedroom of her Levelland home, surrounded by memories of her father. Michael had grown up here too, but he had helped Liz transform its dated fifties style into something more modern. They had replaced the old turquoise tile, installed a new sink and cabinets, and put French doors between the living room and the dining room.

In the corner of her bedroom, Liz kept a curio cabinet Michael had built for her daughter, Alexis, when she was eight. On one shelf sat a plaster cast of two hands: Michael’s, holding a smaller one belonging to his granddaughter. “Together forever,” read the inscription at the base of the mold, “Alexis and Grandpa. Love always.” Liz thought of the two of them together, how he always gave Alexis three kisses before he left: one on her left cheek, one on her right cheek, and one on her forehead. She thought about how she might never see him again.

In late March, Liz got a phone call from her father’s doctor. Michael was having issues with his kidneys—he’d have one good day, then his condition would seem to take three steps back. The doctor told Liz that she should consider signing a “do not resuscitate” order. Liz’s heart sank, but she remained hopeful. “He’s strong,” she remembers telling her sister. “He’s going to come home, and we’re going to be talking about this over a cup of coffee.”

But on March 31, Michael’s ventilator was set to its maximum capacity. He was on dialysis, but it wasn’t taking well. And his blood pressure skyrocketed.

The next morning, his heart stopped. After 16 days in the hospital, and 25 days after he’d attended the regional basketball tournament in Levelland, Michael Dominguez died.

There was no funeral for him—his family felt restrictions would have prevented a proper goodbye. “We would not be able to touch him, couldn’t kiss him,” Liz said later. She and her family hope to hold a celebration of Michael’s life, whenever it’s safe again to gather in groups.

At the same time, at Northwest Texas Hospital, in Amarillo, Catherine Huseman wasn’t improving either. The doctors removed her ventilator on April 2. She was still heavily sedated, but the nurses thought she could still hear when someone spoke to her, and they connected Huseman’s phone to a speaker in her room. All ten of her children called to talk to her for the last time. She died an hour or so later.

The survival rate for COVID-19 patients on ventilators is low. In late April, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a study that examined the medical records of 1,151 patients relying on ventilators in New York City–area hospitals over a 35-day span. By the time the study was completed, about 25 percent of the patients had died, while 72 percent were still on ventilators in the hospital. Only 38 people—a little more than 3 percent—had been discharged.

For six days in late March, Ralph Albracht lay sedated in the hospital in Amarillo, hooked up to a ventilator. Slipping in and out of consciousness, he had vivid dreams that blurred his sense of reality. In one he was out of the hospital and in the rig of a truck, about to move cement somewhere, but he wasn’t supposed to be in there. His son-in-law was banging on the door of the rig, telling him to get out, to get out of there now—but all Albracht could do was say how badly he wanted to go home. In another dream, it was storming outside the hospital; the windows shattered, and soon the entire room began to cave in. Albracht thought he must be dying.

But after his sixth day on the ventilator, Albracht had recovered enough to be taken off the machine. He was so weak that he could barely lift his legs, and it would take several days for him to stand on his own again. Boredom set in—visitors were prohibited, and he had little to do. There was no baseball to watch on television. He longed to play piano. Doctors wanted to make sure the virus was gone, so he was retested twice. Both times, the tests came back negative, and his nurses told him he would be able to go home soon.

“It’s something I hope nobody has to go through,” Albracht said later. “I know a lot of others didn’t make it after being on the ventilator. Thinking that you’re gonna die alone in the hospital . . . that’s a really sobering thought.”

On Wednesday, April 15, Albracht was released to go home. His nurses told him some of the hospital staff wanted to have a “graduation party” for him; he was one of the first COVID-19 patients the hospital had treated. Albracht figured there would just be a few nurses to send him off. But when he rolled out of his room in a wheelchair and turned the corner, he saw the hospital’s hallway lined with staff holding roses and lilies. He thought it must have been more than a hundred people.

When he stepped outside, he raised his arms over his head in victory and embraced his wife of 56 years before they drove back to their farm in Nazareth.

A week and a half before B’Anna’s burial service, Governor Abbott had banned gatherings of more than ten people, so Billy, his two children, and his son’s fiancée were the only ones at Memorial Park Cemetery in Vega on April 1. Billy had tested positive for coronavirus, but his symptoms never progressed beyond a cough, which cleared up after a few days. The funeral director couldn’t sit down with Billy to plan the service, so the director just used the music that he had planned on playing at his own funeral, read some Scripture, and said a prayer.

A friend of the family set up a GoFundMe account for the Scrogginses, raising more than $25,000, mostly from people in town. Some friends dropped food at his doorstep, and others parked on the street outside his house to pray. One planted a lawn chair on Billy’s front lawn one afternoon and drank a beer with him, while making sure to stay six feet away.

After B’Anna’s death, her son’s fiancée, Renee, periodically posted updates from her ultrasound appointments to B’Anna’s Facebook page. “Everleigh’s weighing 6lbs and 12 ounces,” read one update, posted on April 14. “Her heartbeat is 154! She’s healthy. We miss you so much! Everleigh loves her B’ma.”

On Thursday, May 7, Renee went into labor at Northwest hospital in Amarillo. Just down the street, separated by a few parking lots, was BSA Hospital, where B’Anna had died 46 days earlier.

Renee and B’Anna’s son, Brian, had planned to give Everleigh the middle name Jean, after B’Anna’s grandmother. When the baby was born, they surprised Billy by adding another middle name: Raye, after B’Anna Raye Scroggins. On Saturday, May 9, Billy went to Brian’s house and held Everleigh for the first time. He held back tears as she sat peacefully in his arms.

The next day was Mother’s Day, and Billy visited B’Anna’s grave. He spoke to her about the Papaw Jar, a family tradition in which grandfathers collect loose change in glass jars, to be given to each grandchild on their eighteenth birthday. When Billy began collecting change for Brian’s kids a few years ago, B’Anna poked fun: Brian hadn’t even had a girlfriend at the time, and grandchildren seemed so far in the distant future.

Now, as Billy wrote Everleigh’s birthday on the bottom of the jar, he couldn’t help but think about how badly he wanted B’Anna to be there, about spending the rest of his life without her, and about all of their hopes and plans that had been forever altered by the virus. He thought about all the simple rituals that he no longer had, like sending B’Anna a text wishing her a good day or making coffee for her in the morning. He thought about how, just a few months ago, he’d sat with B’Anna in the stands at the Texan Dome to watch high school basketball.

“Everything was great one day, and now there’s nothing,” Billy said. “My whole life changed in two months.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Health

- Basketball

- Greg Abbott