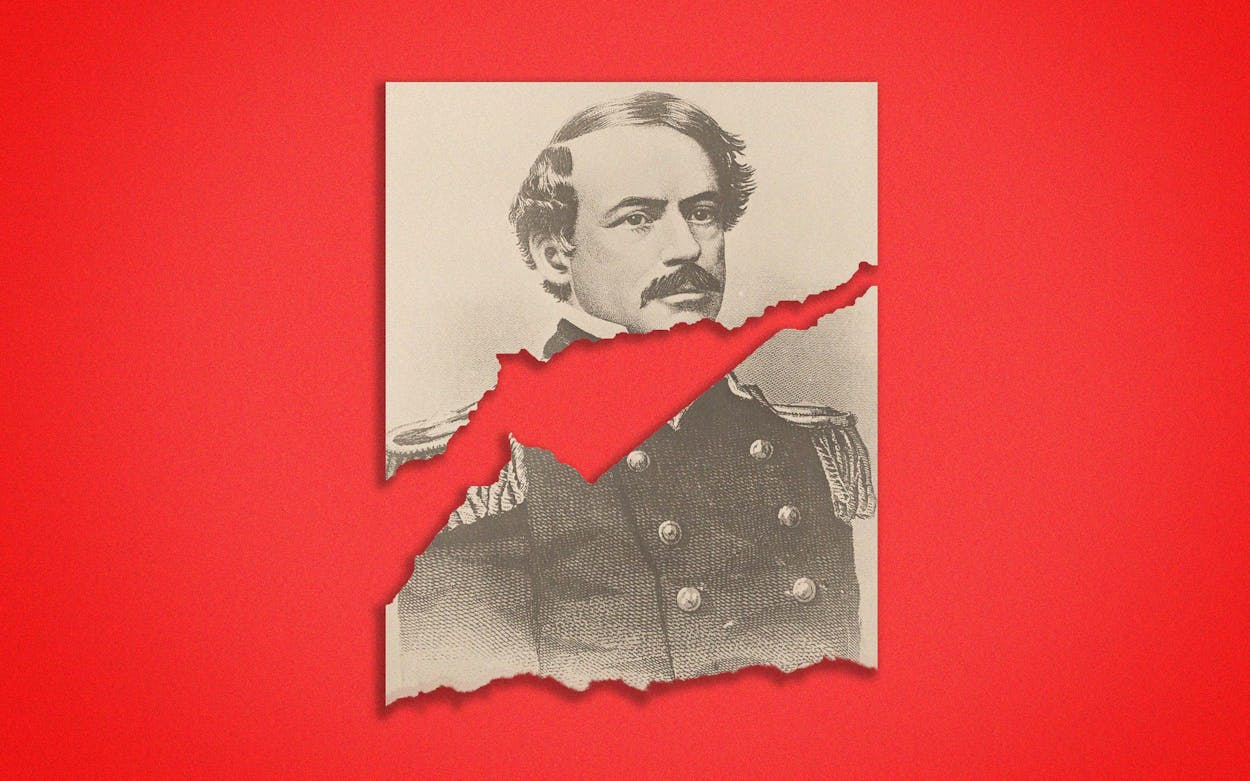

In 2015, the year I enrolled at Southwestern University in Georgetown, the campus chapter of Kappa Alpha Order removed a portrait of Robert E. Lee that had hung over the fraternity house’s fireplace. The general had been, and remains, a central figure in the fraternity’s lore. The fifth chapter of the official KA handbook, which all pledges are required to read from cover to cover, calls the Confederate general the fraternity’s “spiritual founder” and positions him as a role model: “A true gentleman, the last true knight.” There were rumors that fraternity members in Southwestern’s chapter of KA had complicated feelings about this legacy, but direct conversations on the subject were rare. Some in KA drew a line between the chapter here, north of Austin, and the 121 other active chapters elsewhere in the country.

It’s a distinction KA alumni across the country have often tried to draw. In June, Massachusetts congressman and U.S. Senate candidate Joe Kennedy, who was a member of the fraternity at Stanford University, distanced himself from the organization over its “racist record.” One of the fraternity’s founders, Samuel Zenas Ammen, who established 22 active chapters mainly in the South but also at Stanford and UC-Berkeley, wrote in the Directory of the Kappa Alpha Order (1865–1922) that the Ku Klux Klan and KA, both of which were founded within nine months after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, “were reactions against the same evils.” Some groups of KAs referred to themselves as Klans in the KA Journal, an internal periodical, in the beginning of the twentieth century, and in yearbooks through the middle of the century, according to Taulby Edmondson, a history professor at Virginia Tech who has studied the fraternity. “Old South” balls were a national staple of Kappa Alpha social functions from the 1920s until the aughts. This July, after the Southwestern KA chapter cited some of this history in a letter published on social media, the national organization suspended the group for posting the letter without first clearing it and for its “threatening or incendiary” language.

The Southwestern chapter has its own history to contend with. In 1965, the chapter sponsored an “Old South Week” on campus to honor the centennial of the end of the Civil War; frat members donned Confederate uniforms and held a so-called special service at Georgetown’s monument to fallen Confederate soldiers. In 2001, the chapter was suspended by Southwestern for “acts of abuse and disrespect,” which included open hostility toward Black students. Southwestern’s Ebony Coalition, a Black-led student group, reported to the school’s director of student life that its members avoided going near the KA house, fearing for their safety. A disciplinary memo enumerating the reasons for the chapter’s suspension referred to an incident at a party where a fraternity member shouted racial slurs, reportedly while whipping the floor with a belt. The fraternity returned to campus in 2004.

Since then, KA members say some students of color who initially wanted to join the fraternity chose not to after they learned that it romanticizes the Confederacy. Malcolm Conner, who graduated from Southwestern in 2016, left KA his senior year. He felt morally conflicted going from fraternal bonding to “defending my Blackness against somebody who wanted to fly the Confederate flag,” especially after he learned that some of his fraternity brothers who agreed with him were not willing to speak out.

This June, Noah Clark, who rushed in spring of 2014 and became the first Black man active in KA to graduate from Southwestern, noticed fraternity members fund-raising on social media for the Black Lives Matter Global Network. As someone who had grown disgusted by the fraternity’s history, Clark says he was “extremely proud” to see public support from KA members for the BLM movement. He grew convinced that now was the time to address the issue of Lee. In a group chat with active fraternity members and younger alumni, he wrote that they needed “to put pressure on the national organization to allow us to distance formally from historical Confederate ties.”

On July 11, spurred on by Clark, 41 Southwestern KA members and a few younger alumni—who hoped their presence would help active members of the fraternity avoid suspension—sent the national Kappa Alpha Order a draft of a letter denouncing Lee that they hoped to publish. “KA nationally has a deeply troubling history that active chapters can no longer cry ignorance to [sic],” they wrote. “Our chapter has a duty to step up and force changes that will produce more compassionate and well-rounded young men.”

The letter met more backlash than its signers expected, leading to a days-long back and forth between the Southwestern chapter and KA’s national executive director, Larry Stanton Wiese, who works full-time for the fraternity at its Virginia headquarters. The response to the letter, when it was finally posted on social media, was mixed. One commenter wrote, “Never thought I would say this, but proud of the Kappa Alpha chapter of Southwestern!” Another, a Houston attorney and alumnus, compared the active members to a “cancer,” before later deleting the post and apologizing. Within hours, the national KA organization banned the group from initiating new members for the rest of the year.

Over the last two decades, the national organization of KA has banned various old traditions: the display of the Confederate battle flag in 2001, the use of Civil War uniforms in 2010, the hosting of “Old South” events in 2016. On July 1, the fraternity hired a full-time staff member to develop educational programs centered on diversity and the Order’s relationship with Lee. “Past issues,” Wiese wrote, “do not negate present progress.”

Perhaps because of these actions, when Southwestern KA members sent their letter for review on July 11, they thought collaboration with the national organization would help open the discussion about the fraternity’s past. Instead, over the course of two days, Wiese pushed the chapter members to revise their original letter—or, as, KA senior Jeremy Wilson put it, to “water [it] down.”

Members of the Southwestern chapter were eager to avoid suspension, so they made concessions. The version of the letter published on social media on July 13 “call[ed] on,” rather than “demand[ed],” the national organization cut ties with Lee, and referenced the fraternity’s “troubling,” rather than “racist,” history. But the chapter didn’t take all the national organization’s edits. The published version is two paragraphs longer than the national organization wanted, and it emphasizes historic harms KA has ignored “for too long.”

In Wiese’s suspension letter, which banned the chapter from initiating new members until December 2020, he wrote that the Southwestern chapter “misrepresented” its intentions to the national organization. “Releasing a statement regarding your chapter’s stance is not a violation” of the Kappa Alpha Laws, Wiese wrote. “But, releasing a statement after you agreed to submit a revision to the officers, advisors and staff with whom you were engaged does constitute a violation.”

“Likewise, as I advised you on the phone,” Wiese added, “releasing this statement which is threatening or incendiary also constitutes a violation.”

In an emailed statement to Texas Monthly, Wiese noted that “[s]everal other chapters have voiced similar concerns, but all others have been respectful and work[ed] within the required process of the national organization.” KA’s inaugural chapter at Washington and Lee University (where faculty just voted to ask the board of trustees to remove Lee’s name) also denounced the general the week before the Southwestern chapter did and wasn’t punished, according to Inside Higher Ed. Notably, the Washington and Lee University chapter’s letter was more subdued: it didn’t address KA’s history, and only “recommended” that the national organization end all traditions tied to the Confederacy. In late July, Vanderbilt University’s KA chapter published and subsequently deleted a post on social media alleging that members had attempted to write a local mission statement denouncing Lee but were told by the national organization that “it would not allow this action.” (In an email to Texas Monthly, Wiese wrote that the post, which also outlined a history of the fraternity, “contains many inaccuracies and false statements.”)

The Southwestern chapter, whose appeal of the suspension was denied, contends there was no agreement to share revisions with the national organization and that the fraternity’s bylaws do not require chapters to clear public statements with the national organization. Members say they believe they were punished for speaking out too strongly about racism.

“I think [the KA national office] should take the time to study and learn and listen to the people of color in the organization,” Clark said. “I don’t think that they should be trying to silence any of their chapters.”

Although many alumni contributed to the letter from the Southwestern KA chapter, others have voiced dissent on private Facebook pages. One alum who graduated in 1997 wrote, “I choose to remember the good and honorable things [Lee] did in his illustrious life. I will never consider him a traitor.” Another alum from the class of 1991 wrote, “There is no systematic racism … but there is a systematic lack of parenting.”

Conner, now a teacher in Washington, D.C., said he finds hope in what his campus chapter has done since he graduated: “The progression of KA for me is about the social progression of this country more largely.” He said the conversations about race he had with members in his time have continued to the point where the chapter, now made up of students he never knew, feels confident enough to publicly stand up for what they feel is right. “I don’t think that absolves the lack of action for so long, [but] it makes me feel like the discussions I chose to have with people, and my choice of leaving, was not in vain.”

Update: The story has been edited to clarify in which documents certain KA groups referred to themselves as Klans.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Georgetown