Near the edge of a cliff that plunges hundreds of feet down to the shore of Lake Austin, a five-thousand-square-foot steel-frame structure with tentlike walls houses the potential future of ultraluxury real estate marketing: a holodeck.

The term comes from Star Trek, in which Federation starships were equipped with special rooms where crew members could create and interact with holographic environments. At Lake Austin, the enormous space brings to virtual life, in photographic detail, one of the most opulent condo buildings Texas has ever seen. Its creator bills it as the first installation of its caliber anywhere.

Let’s back up. When entrepreneur Jonathan Coon announced his plans to build a sprawling complex along the top of a spectacular ridge overlooking Lake Austin and the downtown skyline, in late 2021, the world was a different place. Interest rates had been near zero for most of the preceding decade, and newcomers were migrating to Texas in greater numbers than ever before. The COVID-19 pandemic had roiled large swaths of the economy, but if you were in high-end Austin real estate, there seemed to be no limit to what was possible.

The parade of tech founders, venture capitalists, work-from-anywhere creatives, celebrities, and entire corporate headquarters that were moving to the area suggested that no price was too high, no amenity too lavish. Even the world’s richest man had moved to Austin.

Hence the 100,000 square feet of amenities Coon had drawn up—including a glass-box funicular to whisk guests from their flats down to a fleet of electric speedboats and a lakefront clubhouse, an indoor citrus grove inspired by the winter gardens of Versailles, and a 76,000-square-foot spa and sports club. Hence the penthouse condos whose 3,000 square feet of wraparound terrace would make you feel as if you’re floating above the lake hundreds of feet below.

With 179 homes and the luxury hospitality company Four Seasons managing the property, Coon’s project seemed inevitable—maybe even overdue, given the hype around Austin. By the February following the property’s announcement, some 50 percent of the homes were reserved by buyers. Construction would finish within about four years, Coon hoped.

“But then Russia invaded Ukraine,” he says now, from the front passenger seat of a Cadillac Escalade that ferries him between the construction site and a trailer at the bottom of the hill. Over the ensuing year, war, supply chain disruption, inflation, the end of the pandemic, and corporate return-to-office policies conspired to change everything. With the Federal Reserve raising interest rates at a faster clip than at any time since the eighties, it was as if someone knocked over the DJ booth and turned on overhead floodlights right as the real estate party was progressing to its champagne-spraying phase. Just last month, a planned high-rise in downtown Austin that was set to become the tallest tower in Texas, at 80 stories, was modified to a much less impressive 45 stories.

For Coon, who made his name as an entrepreneur in entirely different industries before turning to real estate, the moment called for new thinking. His first big success was creating the company 1-800 Contacts, which revolutionized the business of selling corrective eyewear back in the nineties (long before millennial favorite Warby Parker) and eventually sold for $900 million. He also funded the movie Napoleon Dynamite, with his brother.

The standard play to attract more buyers in another trendy real estate market might be to throw a big party and make a scene. If it were the latest skyscraper in Miami, say. One of the realty firms helping market the Lake Austin project, Douglas Elliman, employs exactly that strategy in other cities. “But we’re not going to do those things,” Coon says. In Austin, where every new development arrives to a spate of hand-wringing about the city’s changing character, something a little more restrained would go over better. Plus, Miami-style parties aren’t really Coon’s style. A Richardson native who built 1-800 Contacts in Utah before moving to Austin a little more than a decade ago, he comes off like an all-American dad, albeit one with a streak of techno-optimist superentrepreneur.

Last fall, several pieces of emerging technology caught Coon’s attention—a new virtual reality headset from Meta called the Quest Pro, built for high-resolution collaborative environments; a high-powered Nvidia graphics processor built for rendering virtual worlds; and an advanced new game-development platform called Unreal Engine 5. Together they could enable a new kind of immersive experience in which photorealistic computer-generated images could grow into whole worlds.

Coon had already constructed a four-story viewing platform to show off the sights from his hilltop lot—a 90-degree bend in the Colorado River down below; downtown Austin to the east, perfectly framed between Mount Bonnell and the Dell family’s compound; and the rugged Hill Country unfolding to the west. Now he decided to build his holodeck next to that, so potential buyers could experience the property both inside and out years before it exists. “For people who might think, ‘I know what that is; it’s condos on the lake,’ they can understand how it’s so much more than that once they actually stand in a residence,” Coon says.

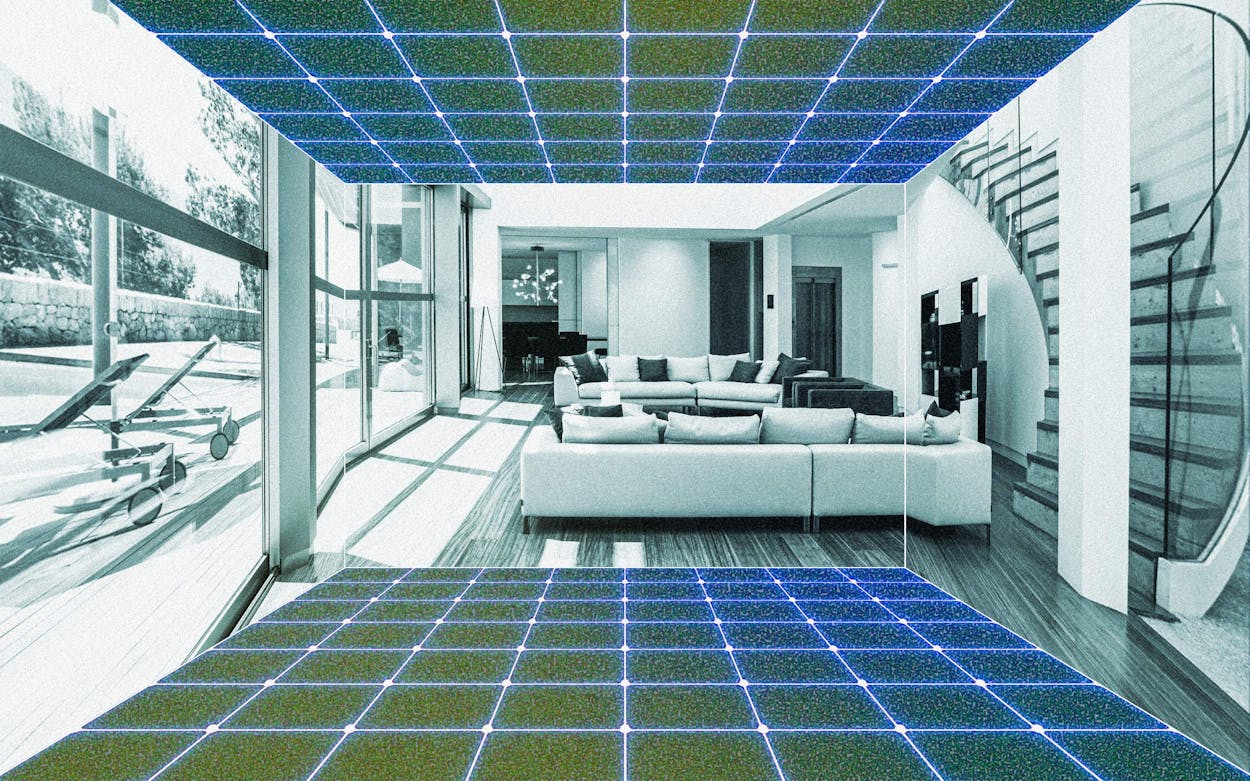

Inside the cavernous virtual reality chamber, a network of green pin lights in the ceiling and blocky patterns on the walls allow the technology to maintain spatial awareness and track visitors as they wander through the space. Slide on a VR headset, wait a few seconds for the machinery to load up a 3D rendering and place you in it, and then be transported as if by magic.

While VR has been widely used in real estate already—from simple applications such as 360-degree photos to more elaborate architectural renderings—this kind of photorealistic tour of a hypothetical space is something new. The architectural VR experiences to date have been more like animation than live action. As many as four people can don the VR headsets and explore the virtual space together, but Coon says that strains the available bandwidth—it simply requires more data than the fastest Wi-Fi network can handle. “We’re really pushing the limit of what you can transmit,” he says.

Coon joins me for my tour, and we spend thirty minutes wandering through a sleek apartment in the sky, the boathouse lounge, a sprawling restaurant, and the enormous spa and sports club, with indoor pickleball courts, an infinity pool the length of a football field, a 140-inch micro-LED TV, and a 32-foot-high indoor slide for the fortunate kids who will one day call this place home. In the apartment, Coon points out a wide bench seat in one of the picture windows and says the design was inspired by the windows at 432 Park Avenue in Manhattan, one of the so-called Billionaires’ Row buildings that sprouted just south of Central Park in the past decade. In the vast primary bathroom, he points out the hidden doors that lead to separate his and hers toilets—“one of the keys to a successful marriage,” he notes.

It’s all exceptionally lifelike, all the way down to glass surfaces that show reflections of the rooms surrounding them and that change in real time as they would in the real world. It’s also slightly nauseating, though it’s hard to tell if that’s from the uncanny-valley effect of occasionally skewed perspectives—a chair out of scale here, a depth-of-field distortion there—or simply the cognitive effect of that much time in VR. Or perhaps the disorienting feeling comes naturally when one passes through a portal into a parallel world of wealth that exists for only a tiny fraction of humanity. The homes here are billed as floating above it all, and that they do.

All of which raises a question: Who is buying these places? It’s not Saudi princes and Russian oligarchs, Coon says. Of the sales to date, about three quarters have been to Texans, and most of the rest have been to Californians planning to be here part-time. To get the tax benefits of being in Texas, an owner has to occupy a house here at least 183 days a year. From Austin it’s roughly equidistant to New York City and San Francisco (some 1,700 miles) as well as to Miami and Los Angeles (1,300 miles). “So they make this their hub.”

At first Coon tried marketing to buyers from all of those coastal cities, plus a few others, including Chicago and Seattle. But in time he found it was Texans and Californians who primarily responded to the pitch. Today Coon’s team scours property tax records in the two states and targets buyers whose homes are appraised at more than $2.5 million here and $5 million in California, on the thinking that the Texans’ homes are probably worth twice their official appraisal values thanks to the state’s convoluted property tax system. As you might expect, those potential buyers receive a brochure in the mail, but in this case the brochure takes the form of a nearly six-pound, hardcover coffee-table book full of glossy pictures. If a prospect shows interest in learning more, they get invited to come experience the holodeck.

The strategy, Coon says, “is kind of obvious. People who live in expensive houses buy expensive houses. That’s it.” To date, about two dozen people have experienced the holodeck, though only about half of those were potential buyers. “Some of these people come with entourages,” he explains. “Two of those who have seen it are possibly moving forward with a purchase.”

It all seems like an extraordinary amount of effort and investment to fill a condo complex in Austin, but such is the reality of the new market in the Texas capital, even as the pandemic-era boom has waned—or perhaps because of that. I ask Coon if he plans to turn his new technological property-marketing marvel into a product itself—the kind of thing other developers might pay top dollar for. He’s an entrepreneur, after all. But no, he says, others will stitch these different pieces together soon enough, as the prices of the components come down, and holodecks like his will become standard fare, at least for top properties like this one or, say, a new tower on Billionaires’ Row. “You’re seeing the future of real estate here,” he says.

Coon decided to build this development in the first place because he and his wife fell in the love with the idea of creating their dream home at this location. Since the land was too expensive as a one-off homesite, they planned a whole amenity-rich community. They will be among the first residents when it opens in 2025.

In the meantime, they can walk around their future home whenever they want—in the holodeck.