This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

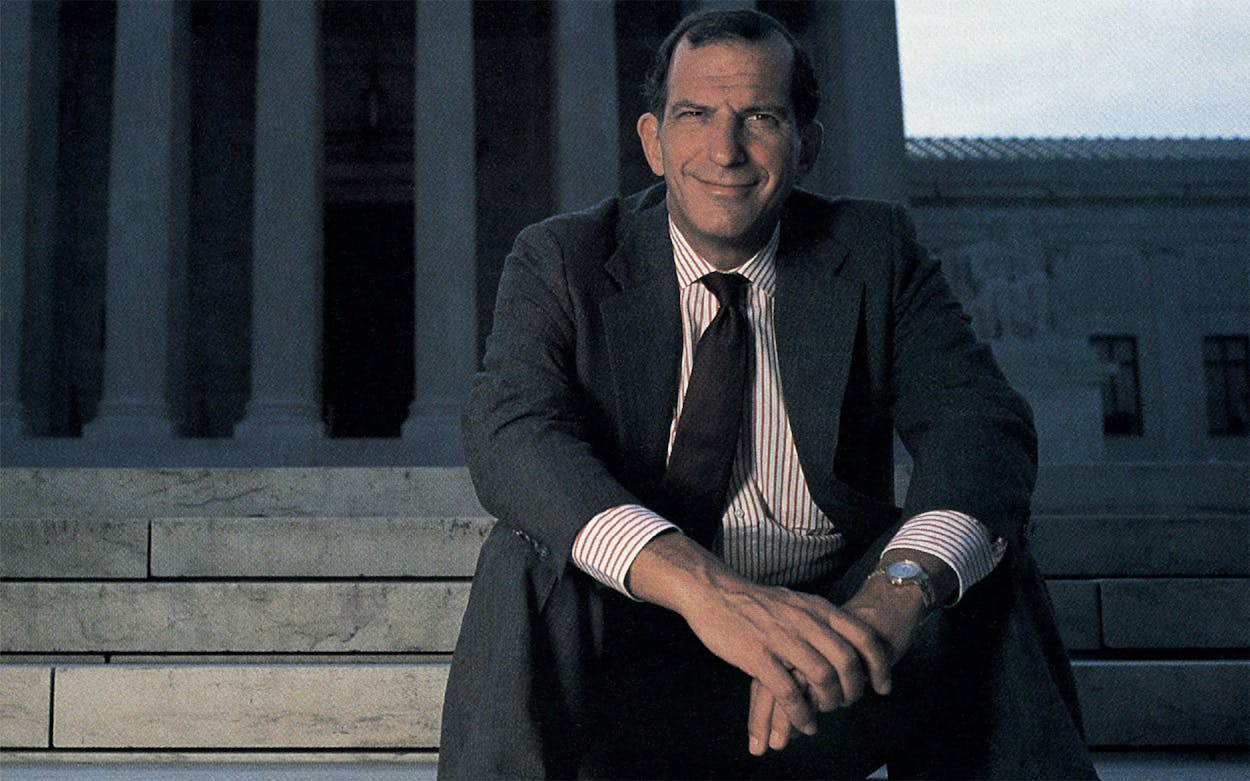

Stephen D. Susman, 48, rose to make the biggest speech to the biggest audience of his life. His face wore a burnished tan from a weekend in the Bahamas, but it also betrayed the strain of long hours and the knowledge that he was an outsider facing hostile judges. His soft drawl, calculated casualness, and hard rhetoric telegraphed a warning: Don’t underestimate this Texan. His performance was strikingly physical. He gestured constantly and, to the distress of cameramen broadcasting live on CNN and C-SPAN, marched between the podium and an easel holding greatly enlarged exhibits. Arching his back as if to relieve an overwhelming tension, he threw his chest so far forward that his lapels were pulled askew. Addressing the twelve congressmen on the dais in front of him, he began, “Mr. Chairman, members of the committee, I’m Steve Susman. I’m Jim Wright’s lawyer. I’ve been wondering for the last few days what I am doing here.”

What he was doing there was simple. He was hoping to perform a legal miracle that would save the fast-sinking 34-year congressional career of House Speaker Jim Wright. After a year of investigations and press leaks, Wright had been charged by the House Committee on Official Standards—the House Ethics Committee—with taking gifts from Fort Worth businessman George Mallick, gifts that were prohibited because Mallick supposedly had a direct interest in legislation, and with selling in bulk a book of his thoughts as a ruse to evade limits on outside income from speeches. What Steve Susman had to do was to persuade the members of the Ethics Committee that as a matter of law they had made a mistake. He had to present such an irrefutable case that the same members who had voted to charge Wright would now vote that the Speaker had done no serious wrong.

If Susman accomplished that miracle, a second might follow: Steve Susman, an energetic comer from Houston, would join that small pantheon of lawyers whose names have become household words—men like Clarence Darrow, Louis Nizer, and Edward Bennett Williams. In any event he would become his generation’s counterpart to Houston’s two legendary superlawyers, Richard “Racehorse” Haynes and Joe Jamail.

Susman based his argument to the committee on a strict interpretation of House rules. He said that however close Jim Wright may have come to the line, he did not cross it, and therefore the Speaker was being condemned for acts he did not commit. Susman was making a legal, technical case for what had become a moral and political issue. He argued that Wright, whom the media considered already a dead man, deserved due process and his day in court to respond to the charges instead of what Susman called “a lynch mob or a conviction based on guilt by association.” Susman cogently summarized the substance of the 69 charges against Wright that reporters repeatedly referred to in their stories: “The occasional use of a tiny apartment—one-bedroom apartment—in Fort Worth; the use of a five- to nine-year-old automobile that he owned half of anyway; seven thousand seven hundred [dollars] in book royalties spread over a three-year period; and a nine-thousand-dollar-a-year salary from a company that he owned half of and that his wife worked for.”

But it was clear from the looks on the committee members’ faces as Susman spoke and from the tenor of their questions that afternoon that the miracle was not happening. Late that evening, facing Ted Koppel, America’s chief justice of public opinion, Susman could not overcome the appearance that his client was guilty. Responding to Koppel’s tough questioning, Susman looked like a stereotype from a thirties gangster movie—the crime boss’s smart mouthpiece defending an obviously guilty man with infuriating legal technicalities.

Though Wright was doomed, Steve Susman wasn’t. “Lawyers do not lose—clients lose,” goes the axiom of the profession. Edward Bennett Williams, for example, made a name for himself by defending Lyndon Johnson’s protégé Bobby Baker, who ended up going to jail. Susman may not have performed a miracle on Wright’s behalf, but he acquitted himself honorably, raising the level of the ethics debate and using his motions to smoke out the panel’s likely action against Wright. In the end, Jim Wright would resign and return to Texas with his professional life ruined, his reputation in shambles. Steve Susman, however, would return to Texas as the lawyer one of the most powerful men in the country had turned to in his hour of need.

Humility and self-doubt are not the hallmarks of a successful trial lawyer. Susman offers this assessment of his presentation to the Ethics Committee: “I’m happy with the way I handled it.” And he is glad he took the job. “I loved it. It was wonderful fun,” he says. That the result was not what he would have liked is not his fault. He says that is the fault, for one thing, of a biased Ethics Committee. “I was not very happy with the questions I got,” he says. “I guess that was the first time I really got an indication that these f—ers are not likely to change their minds. It was clearly an unfriendly panel by and large, and the questions were loaded.”

That the result was not what he would have liked is the fault, for another thing, of his client. By resigning from the speakership before the Ethics Committee ruled on the appeal, Jim Wright, in effect, blew Susman’s case. “My advice to him,” recalls Susman, “was, ‘Mr. Speaker, I hope you do not resign, if you are going to resign, until after the committee rules. Make them do their work. Don’t let them off the hook. If you resign before they rule, our efforts will have been in vain.’ ”

Susman believes one of the biggest mistakes Wright made during his whole ordeal was to wait until early May to hire him or any equivalently talented lawyer. Susman thinks he should have been on retainer since last summer. If he had been, he says, he would have been able to do something about the release of the mortally damaging 279-page report from the special outside counsel, which gave the press a road map of Wright’s alleged lapses. “I would have cried foul so loud that you could have heard it from one end of the country to the other,” says Susman. “I would have gone public immediately. I would have taken Jim Wright’s defense on the merits to the public immediately, had him appear on television, had him make speeches, had his wife appear. I’d have hired a PR person to illustrate that the investigation is nonsense.”

On the other hand, Susman admits that forces perhaps more powerful than his own legal mind were in motion. “It’s the press,” he says. “The thing that has surprised me so in this is how when the snowball of public opinion gets rolling, there’s no way of getting in front of it. It’ll roll you over.” Of course, that works both ways. Susman’s latest set of clients puts him on the safe side of the snowball. Leaving Washington two days after his big presentation, Susman flew to Anchorage, where he is representing a group of Alaskan fishermen in their suit to force Exxon USA to pay damages from its disastrous oil spill into Prince William Sound.

Susman’s name came to Jim Wright’s attention through an obvious route, the middle-aged-boy network. Before Wright, Susman’s most prominent clients had been the billionaire Hunt brothers. He had represented them at a desperate point in their suit against 23 of the world’s largest banks, which were trying to foreclose on their empire for payment of a $1.5 billion debt. Meanwhile, the Hunts’ Placid Oil bankruptcy was being handled by Henry Simon, a Fort Worth attorney who also did work for Wright—and who in 1979 had handled the incorporation of Mallightco, the business partnership between the Wrights and the Mallicks that was to bring the Speaker such grief.

Simon recommended Susman to Wright because Simon had been impressed by the Houston lawyer’s ability to make the big banks blink. The banks had agreed to renegotiate their loans with the Hunts after Susman, hired at the eleventh hour, achieved two masterstrokes: winning a key ruling, thus keeping the brothers’ case alive before an unfriendly federal judge, Barefoot Sanders, and persuading the Hunts to sit still for an intimate cover story in the New York Times Magazine that made the brothers appear if not stupid, at least like underdogs and unsophisticated bumblers who might well have been gulled by the banks. For his trouble, Susman was rewarded with fees of $600 an hour, a 50 percent premium over his then-standard fee. His firm garnered billings of several million dollars. Today Susman’s regular fee is $475 an hour, but because Susman knew that Wright was not wealthy and because the publicity Susman could gain from defending the Speaker would be priceless, he agreed to the same fee that the Ethics Committee paid its outside counsel—$1,000 a day. That amounted to less than $85 an hour for one of Susman’s typical twelve-hour days.

Steve Susman was destined to be a smart lawyer. His father, Harry Susman, who practiced law in Houston, was a graduate of Yale University Law School and an editor of the Yale Law Journal. He dropped dead of a bleeding ulcer at fifty, when Stephen was eight. Stephen’s mother, Helene, forced to support him and his young brother, dusted off her own law degree and resumed her practice.

Susman was raised in the Riverside section of Houston, home to the city’s affluent Jewish families, who were then barred by deed restrictions from living in the city’s premier neighborhood, River Oaks. (In 1983 Susman and his wife, Karen, a business-and-family-law attorney, had the sweet satisfaction of buying a home in River Oaks, a large contemporary house complete with a lighted swimming pool.)

Drawing on family tradition and following the standard set by Houston’s upper crust, Susman went east to college, to Yale, where he managed the student laundry and graduated magna cum laude in English. Then, as befits someone who planned to make his home in Texas, he shrewdly returned to the University of Texas for his law degree. He was the editor in chief of Texas Law Review and claims the highest grade-point average in the law school’s history. He continued collecting impeccable credentials clerking in Houston for federal judge and noted desegregationist John R. Brown, and then in Washington for U.S. Supreme Court justice Hugo Black.

Susman returned to Houston in 1967. Old guard Houston law firms, including the one now known as Fulbright and Jaworski, were being pressured to change their apparently discriminatory hiring practices. Susman was one of the first observant Jews to be offered a job at Fulbright. Though he eventually became a partner, it was not a good match. Susman was smart and worked hard, but he ruffled feathers. Some considered him arrogant. “He’s not a terribly thoughtful person,” acknowledges his brother, Tom, an attorney in the Washington office of a prestigious Boston firm. “His sensitivity to people around him is not great.”

There was, however, a common element between the firm’s style and Susman’s. Fulbright lawyers frequently engaged in the sort of practical joking that Susman also loved. But even then, Susman pushed the tradition farther than anyone else. For his most famous escapade, he enlisted an acquaintance, Carter Townley, who worked in a local art gallery. Susman and co-conspirators at the firm faked an impressive résumé for Townley, including such outrageous touches as an abstrusely titled paper on tax policy for the nonexistent University of Denver law review and a non–leap year February 29 birthdate.

By the time Townley showed up for his job interview with the firm’s partners, Susman had planted a rumor that Townley was about to be snatched up by the rival firm of Baker and Botts. Townley, thoroughly prepped for his interview, proceeded to make an excellent impression. The Fulbright hiring committee took the bait and made him an offer. After a company party that night, Susman invited colleagues, including potential new hire Townley, to a party at his home. After the party got under way, Susman played a tape that sounded like the old radio serial The Shadow and included surreptitiously recorded selections from the partners’ interview with Townley. Everyone laughed, but later it was said that some senior partners were not amused.

Around the same time, Susman’s star was dimmed when he lost a big antitrust case. Dissatisfied at Fulbright and interested in an academic career, Susman left his law practice to teach antitrust law at his alma mater, the University of Texas. He was happy at UT. Susman’s wife, Karen, observes, “His colleagues really appreciated Steve in a way he was not appreciated at Fulbright, where they didn’t like his style.” Karen was less happy. She was an Austin native who felt she had outgrown the town. She also wanted her husband to make more than the $25,000 a year paid to law professors at the time. “Steve was very serious about staying and teaching at Texas,” she says. “I said, ‘Great, but I’m not going to be there.’ ” She had, in fact, already returned to Houston to enroll their two children in a private school.

Susman returned to Houston to be with his wife and children. But he decided that as long as he was pursuing money, he wanted to pursue lots of it. He didn’t want to go back to an established firm where young partners and associates supported older partners and where he couldn’t expect to make big money until he was in his fifties.

He decided to specialize in a new area of law. The kind of work Susman had done at Fulbright involved defending giant corporations. But there was an emerging, potentially highly lucrative field based on suing such corporations for price-fixing on behalf of smaller companies that were their customers. Known as antitrust class action cases, the suits required that the lawyer work for no fee up front, gambling that if the suit went his way, he would recoup by taking a substantial amount of the judgment. In the mid-seventies there were no plaintiff’s antitrust firms in Texas. That practice was controlled by lawyers in Philadelphia and Chicago. Believing in both preparation and his connections, Susman arranged to be introduced to some of the most successful plaintiff’s antitrust lawyers. Not surprisingly, he returned to Texas convinced he was every bit as smart as they were and could create a niche for himself in Houston.

Susman joined the firm of Mandell and Wright, which specialized in personal-injury and admiralty law; he was to set up its commercial-litigation section. Before long Susman was on the road to fame and riches, a road that was paved with cardboard.

One day in the fall of 1976 a potential client came in. He was the sales manager for a small corrugated-box company, and he was being called before a federal grand jury looking into industry price-fixing. After Susman heard the man’s story, he knew he didn’t want to represent him. Instead Susman wanted to take on the whole industry. He realized that there was a conspiracy on the part of corrugated-box makers to fix prices. Using the principles of antitrust class action, Susman could sue the manufacturers on behalf of companies that purchased the cardboard boxes and sheets from them. He enlisted the services of a lawyer he had brought into the firm, Gary McGowan, and the two of them and others spent the next several years proving their case.

Before it was over, Susman and McGowan had formed their own firm (McGowan recently left; the firm is now Susman Godfrey). It and 55 other law firms had gotten in on the action. In 1983 it all paid off—big. One manufacturer, which insisted on going to trial, was found guilty. It and 36 other companies settled to the tune of $550 million. U.S. district judge John V. Singleton awarded attorney’s fees of $40 million. Susman, who had been the chairman of the plaintiff’s steering committee, and his firm came away with the largest award, a whopping $7.6 million.

The money helped ease the regret of not pursuing a life in academia. Susman and his wife began an aggressive campaign to enjoy themselves. They have continued their tradition of throwing offbeat parties. They take frequent exotic vacations. Karen is on the boards of the Houston Grand Opera and the Houston Symphony, and Steve is on the board of the Contemporary Arts Museum. “We have an incredibly busy social schedule,” Susman says, “parties, gallery openings, black-tie affairs.” Steve’s heavy workload and all of that socializing leave little time for intimate friendships. “I have very, very few close friends in Houston,” outside his firm, Susman says, “because I don’t have time for close friends.”

When Susman isn’t “relaxing,” he is working. His firm is made in his own image. Texas Lawyer calculated in 1987 that Susman Godfrey generated more revenue per lawyer than any of the top ten revenue-grossing firms in Texas. With a generous compensation structure that allows aggressive young lawyers to “eat what they kill,” Susman (“Dad” to his flock) has filled his firm with academic whiz kids, most of whom clerked for federal judges. The firm has grown from 6 to 35 lawyers in eight years.

Even for a man with a keen appreciation of his own abilities, Susman had achieved remarkable success. But he wanted more. He wanted fame. Snagging the Hunt brothers as clients helped. So did his inclusion in The Litigators, by John A. Jenkins, a book that profiles six lawyers dubbed “the entrepreneurs of adversity.” Susman claims he has been simply too busy to read the book, which characterizes him as a hit-man lawyer. But he has bought and given away more than a hundred copies, some of which he has sent to friends with a note that crows, “I didn’t even have to pay to get this published.”

For sheer impact, however, nothing could match defending the imperiled Speaker of the House of Representatives. It would mean Susman would be the lead item on the network news. It would mean his face would likely be on the front page of every major newspaper in the country. After the initial contact was made, each man had some lingering concerns about the other. Susman turned to his brother, Tom, and his friend, Yale president Benno Schmidt, for counsel. Susman wanted to take the job, but could it backfire somehow? Tom reminded him of UT constitutional scholar Charles Alan Wright, who had gotten burned during Watergate because of his defense of Richard Nixon’s decision to withhold White House tapes that turned out to be highly incriminating. But it seemed unlikely that explosive new revelations about the Speaker would come to light. As long as Susman did his best, he couldn’t lose.

The Speaker was distressed that among Susman’s clients was Frank Lorenzo’s Eastern Airlines in its suit against its mechanics union. Wright, a defender of the common man, did not want to be a unionbuster by association. Susman parried that he didn’t get involved in the righteousness of his clients’ causes and that if all his clients had to agree, he’d have little business. Over the next week Wright interviewed a handful of other lawyers, then offered Susman the job.

In the end, events overtook Susman’s defense. He had his hour on the stage, but the roiling series of investigations, accusations, and resignations that made up the recent fare of the House of Representatives shut down Susman’s drama. But he won’t brood. “You never look back with these things,” he says. Now he’s in Alaska, aiming to stay on the side of the angels, representing those injured in the biggest environmental catastrophe in U.S. history.

There would, of course, be one way to recapture the Washington spotlight. The Democrats, so the drumbeat goes, are preparing to get even with the man who started the campaign against Wright. They are gunning for Republican Newt Gingrich, who may have a questionable book deal of his own. In a telephone interview from Anchorage, Susman is asked what he would do if Gingrich asked Susman to bail him out. As Susman answers, it is clear how enticing the prospect is. “No,” he replies. “It’s one thing to have done it for the Speaker of the House. I think it’s a different thing to do it for any congressman. Would I do it for Newt? I don’t know. The answer is, I don’t think so. The answer is, I don’t know . . . I might.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston