This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Stormie Jones was sick again. Her symptoms—a slight fever, nausea, a sore throat—suggested the flu. It was Saturday, November 10, 1990. Thirteen-year-old Stormie was counting on seeing a movie that day in Fort Worth. But by midmorning, she was feeling lethargic, unwilling to drag herself from the warmth of her bed. Reluctantly, she agreed to see a doctor. By the time she and her mother, Susie Purcell, arrived at the hospital, Stormie was pale and noticeably weaker. Leaving the car, she took a few halting steps before collapsing in the parking lot. Later, stretched out in the emergency room, Stormie complained that her feet were cold. Bending over the end of the hospital bed, Susie lowered her forehead to her daughter’s feet, her dark hair falling over them like a blanket. For a few moments, she cradled her daughter’s feet in her hands. Looking up at Stormie’s neck, she noticed something odd: the rapid rise and fall of a throbbing vein.

Within hours, Stormie and her mom were on a flight to Pittsburgh. The journey was not an unfamiliar one. For more than six years, ever since she had become world famous as the first person to receive a combined heart and liver transplant, Stormie and her mother had been shuttling cross-country from their home in Texas to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. As always, when they boarded the plane that night, a cluster of journalists was waiting at the airport gate. One of them, reporter Betty Smith from KDFW-TV in Dallas, was going along on the flight. This would be Betty’s third trip to Pittsburgh to cover the Stormie Jones story.

The plane was nearly empty. Stormie and Susie were the only passengers in first class. After 45 minutes Susie sent a flight attendant back to Betty with an invitation to join them. As she sat down, Betty could see that Stormie was edgy and uncomfortable. Seated next to the window, her shoes off and her feet propped up in front of her, Stormie was shifting awkwardly. “She’d twist around one way and then the other,” Betty recalls. Stormie asked for a glass of water but took only a sip. “1 wanted to reach out to her, but there was this barrier,” Betty says. “I wanted to say, ‘Look, I’m different from the others—I’d like to be your friend,’ but there was no way you could. I was just another reporter to her.” Stormie spent the remainder of the flight in silence, staring out at the blackened sky.

Shortly after midnight, the plane landed in Pittsburgh. As Stormie and her mother got up to leave, Betty made a final gesture. “Stormie,” she said, “if there’s anything you need, your mother knows where to reach me.” But Stormie didn’t answer. Betty watched them head toward the ambulance, Stormie in a wheelchair, Susie at her side, holding her daughter’s stuffed koala bear. Nine hours later, Stormie was dead.

Perhaps it was appropriate that a journalist should have witnessed Stormie’s last flight, the final chapter in the meticulously documented chronicle of a sick little girl on the edge of medical technology. Reporters had recorded in vivid snapshots every milestone in Stormie’s long and arduous journey: Stormie at the airport, departing for Pittsburgh. Stormie waving from the recovery room. Stormie coming home to Texas to resume her supposedly normal life. Wherever Stormie went in public, reporters followed. Publicity was as much a part of her life as illness.

But reporters told only part of the story. Their images distorted, simplified, and sensationalized what Stormie and her family experienced. In a play against reality, Stormie became the perfect child. Yes, she had an adorable bear collection. But she also stuck out her tongue. Yes, she was brave. But she also had horrible nightmares. If reporters knew the darker side of Stormie’s experience, they didn’t tell.

Doctors, too, used her for their own purposes. To them, she was a patient with a rare and fascinating disease. They tried out their latest procedures on her and performed endless exams. They made lengthy entries in their charts about the state of her organs and her responses to various medications. They published scholarly articles on their findings. Yet they did not address her deeper problems.

To the doctors, Stormie was a case history. To reporters, she was a fairy tale. Both were a kind of fiction masking the unsettling truth—that the child with the freckles and the chipmunk face was, in the hands of the well-meaning medical and media professions, a victim.

For the first half of her life, Stormie suffered from a rare and deadly disease. She was rescued by a daring operation that cured the disease but introduced a second set of problems, the repercussions of organ transplantation. As a medical pioneer, Stormie endured extra burdens. Without her historic transplant, she would have been dead at the age of six. With it, she was able to experience adolescence and make a contribution to medical science. But at what cost?

The day she died, reporters caught up with Stormie’s stepfather, Alan Purcell, just before he boarded a plane to Pittsburgh. With curtness, for he detested talking to journalists, he summed up his jumbled feelings. “There’s a lot of sorrow and a lot of upset,” he told them, “but the pain for her is over. She went through a lot of pain, you know, as a guinea pig and as a necessity. What else can we say? She doesn’t hurt no more.”

When Stormie Dawn Jones was three months old, strange bumps began to appear on her knuckles and wrists, on her heels and buttocks, and in the webs between her fingers. Yellow-orange, the color of a duck’s bill, they looked like smooth warts. Mystified, Susie took her daughter from doctor to doctor. “It was horrible,” Susie says. “They’d stick straight pins, pencils, into these lesions to see if they’d bleed.” But no one could say what they were. By the time she was four, Stormie couldn’t even wear shoes—the bumps made them fit so badly they rubbed her feet raw.

Susie was living with Stormie and her older daughter, Misty, in Cumby, a small East Texas town. She had left the girls’ father, an oil-field worker, and was working as a waitress. Money was tight. In the summer of 1983 Susie took Stormie to yet another doctor, a dermatologist who biopsied the lesions and found they contained almost pure cholesterol. He referred Stormie to David Bilheimer, a cholesterol specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Dallas.

Bilheimer knew instantly what was wrong. The lumps were classic signs of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. It was a rare genetic disease, the result of an unlucky combination of mutant genes inherited from each of her parents. Stormie’s genes lacked the protein receptors that metabolize a kind of cholesterol known as low-density lipoprotein, or LDL. Without the receptors, there was no way to filter cholesterol from her bloodstream. Bilheimer discovered that her cholesterol level was 1,100, seven times that of a normal six-year-old. When he placed a stethoscope to her neck, he heard the whooshing sound of blood forcing its way through constricted passageways. Stormie was in imminent danger of a heart attack.

Aside from the lesions, Stormie looked like a perfectly normal plump and blond six-and-a-half-year-old. She was a quiet child, shy and observant. Nurse Marcia Roberts remembers drawing blood from Stormie’s arm in September 1983. “I just couldn’t believe that somebody so cute and so young could have something so devastatingly wrong with her,” she says.

Bilheimer placed Stormie on a low-cholesterol diet and a regimen of experimental drugs. But almost immediately she began to get sick. In early October she said she had a sore throat, but the doctors couldn’t find anything wrong. Stormie continued to complain for several days, until finally they began to suspect she was simply trying to get attention. Then, on October 12, Stormie had a heart attack. The sore throat had been an unusual form of angina, the pain caused when too little oxygen reaches the heart. At the end of the month, Stormie underwent a double bypass to direct more blood to her heart. Then Stormie and Susie went home to Cumby.

On December 10 Stormie once again complained of pain, this time in her chest. She was rushed to Dallas, but doctors think that even before she got there she had another heart attack. Catheterization showed that one of her bypasses was already blocked; the other would soon be as well. In a second operation, she received another bypass and an artificial mitral valve. But these were all stopgap measures. By late December she was suffering more angina. “At that point, it was clear that things were not going to go on much longer,” says Bilheimer. Susie was told that her daughter had less than a year to live. Her family began to make plans for a funeral.

Had Stormie shown up in Dallas months earlier, the doctors would probably have had no choice but to let her die. But timing worked in her favor. In the late seventies, Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein, two Dallas researchers, had identified and explained the cholesterol-metabolizing role of the LDL receptors (work that later won them a Nobel prize). Building on their studies, other Dallas researchers, in the months just before Stormie’s first heart attack, had conducted cholesterol-related experiments on rats and hamsters. One of them, John Dietschy, had shown that more than half of the LDL receptors were located in the animals’ livers. Still unknown was whether Dietschy’s model held true for human beings.

This research led Bilheimer and his colleagues to a radical idea. Why not replace Stormie’s faulty liver with a healthy one, one that might correct her metabolic disease? Until that point, liver transplants had been performed only on patients whose livers were barely functioning, having been devastated by hepatitis, for example, or cirrhosis. Yet by all the established medical criteria, Stormie’s liver was working perfectly. Its only defect was that it did not manufacture LDL receptors. Exactly how important that was, no one knew.

At the time, only two major institutions in the country were performing liver transplants: the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Minnesota. Pittsburgh had the bigger program by far; it was and still is the nation’s busiest transplant center. The success of the liver program was due to one man, the renowned surgeon Thomas Starzl. A tireless, mercurial man, Starzl had performed the first successful liver transplant on a human being in 1963 after experimenting on hundreds of dogs.

In December 1983 Stormie and her mother flew to Pittsburgh so that Starzl could evaluate Stormie. Right away he realized that her damaged heart posed a serious problem. Even if a new liver could correct her metabolism, her heart might be too weak to withstand the operation. Moreover, the immunosuppressive drugs that were required after transplantation to inhibit her body’s immune system and prevent rejection of the organ would leave her artificial valve vulnerable to infection. A liver transplant alone was out of the question. Stormie’s only chance, Starzl reasoned, lay in a daring procedure, one he called a draconian measure: a combined heart and liver transplant.

If the notion of transplanting a liver to correct a metabolic problem was remarkable, the idea of transplanting a liver and a heart together was even more extraordinary—“typically Starzl-esque,” says one Pittsburgh surgeon. “It is just like him to take a giant step forward, whereas others would have hemmed and hawed.” In 1983 liver transplants were still extremely risky. Rejection of the organ was the biggest threat. Even with cyclosporine, which had been used as an experimental immunosuppressant since 1979, single-organ transplant patients had a 25 percent chance of dying in the first year. But Starzl’s proposal was on a different order altogether—the transplantation of two separate organs. Other surgeons had experienced limited success with combined heart-lung transplants, but in that operation, both organs are removed from the donor together and placed in the recipient patient together, as a unit. Starzl intended to perform essentially two separate transplants in different parts of the body at the same time.

Starzl and his colleagues explained what they had in mind to Stormie’s mother. But she had never even heard of an organ transplant. “You’re going to do what to my child?” she asked. One of ten children of tenant farmers in the Panhandle, Susie was only 27, unsophisticated, excitable, and intensely protective of her daughter. She was also blind in one eye—which gave her a haphazard, unfocused look. While some on the medical staff were quick to characterize her as a typical hysterical parent, others were struck by the enormity of her load. “At the time, I was thinking, ‘I can’t believe she’s this young,’ ” one recalls. “ ‘She’s a single parent trying to take care of Stormie, trying to take care of Misty, and trying to take care of herself.’ ”

Money was a big concern. Susie had quit her job as a waitress to take Stormie to Pittsburgh and had no means of support. But at the time, the Pittsburgh medical center accepted all children needing transplants regardless of family resources. “They said their first priority was to save Stormie’s life,” Susie says, “not to worry about money.” With that aside, Susie’s options were frighteningly clear: Go through with the double transplant, or take Stormie home to die.

Susie has often said that, in the end, she let Stormie make the decision to go ahead. But few people think a child that age is capable of comprehending such a momentous decision. “A six-year-old doesn’t really understand about death,” Pittsburgh child life specialist Lyn Mulroy says. “They just don’t understand that it’s forever.” But Susie was a single mother, 27 years old, and faced with a terrible choice. None of her relatives, including Stormie’s father, supported the transplant. Against their wishes, in a faraway and unfamiliar city, she was asked to place her child’s future in the hands of strange doctors. Perhaps it was easier for Susie to “let Stormie decide” than to bear the entire weight alone.

They waited 44 days for a donor. For Starzl it was a race: He had to find a donor before time ran out and Stormie died. While he typically matched donor organs and recipients by height, in this case he carefully measured the girth and length of Stormie’s chest to be certain of the dimensions. And then he too could do nothing but wait. Susie was constantly at her daughter’s side, sleeping on the floor when no cot was available. At times she would go to the medical library and muddle through scientific articles about Stormie’s disease. Her older daughter, Misty, stayed at home in Texas, first with friends in Cumby and later with her grandparents in Amarillo. After one half-hour phone call during which Susie and Misty cried the whole time, Susie didn’t telephone Misty anymore. She wrote instead.

On February 13 Starzl got word of a four-and-a-half-year-old girl who was brain dead after a car accident in Rochester, New York. She was only slightly larger than Stormie, and her organs were in perfect shape. At five-thirty that afternoon Starzl and an associate flew to New York to remove the girl’s liver and heart. They were back in Pittsburgh by eleven-thirty. By the following afternoon, both transplants were completed, and Stormie was wheeled into the intensive care unit, in critical but stable condition.

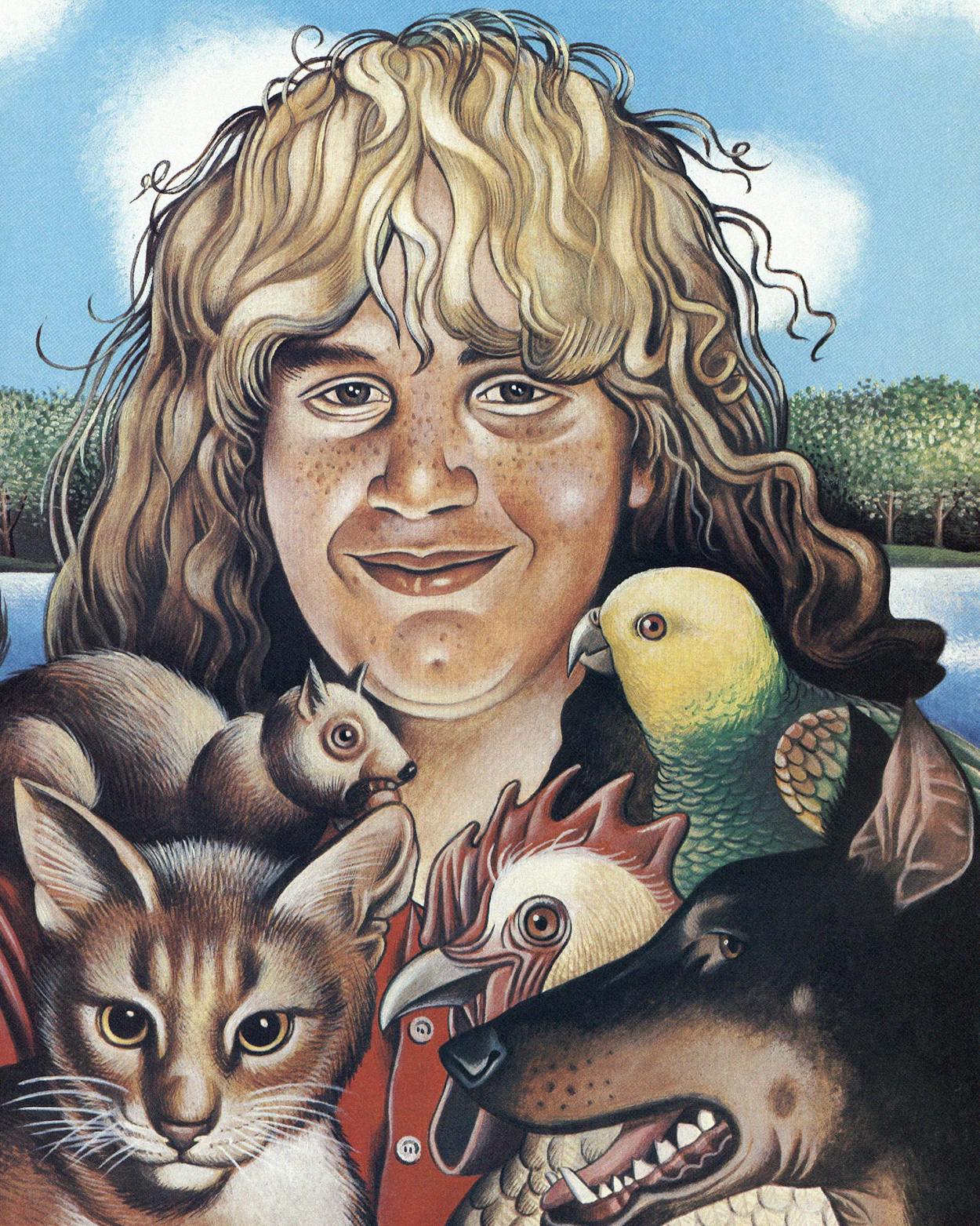

The story of Stormie’s operation was broadcast around the world. A little girl, snatched from the brink of death, was given a new liver and heart . . . on Valentine’s Day! Stormie was an instant celebrity. A week after the surgery, photos showed her smiling placidly in Starzl’s lap. Later the cameras captured her skipping across the hospital playroom, vigorous and full of life: a miracle child.

But to her fellow patients, there was a down side. Some of the would-be recipients had been waiting many months for matching organs. Many had died waiting. The patients and their families were under enormous stress, emotionally and financially spent. “Then Stormie Jones came to Pittsburgh,” says local author Lee Gutkind, who wrote a book about organ transplants. “There was a great deal of excitement about the medical breakthrough, but there was also resentment.”

For Stormie, there was a down side as well. That became apparent at her first press conference only three weeks after the transplant. Dozens of reporters and photographers had set up their equipment in an auditorium at the hospital. “All of a sudden the double doors opened and here comes Stormie,” recalled Dennis Johnson, the medical reporter for WFAA-TV in Dallas. “There was a pause, and then, for some reason, this gaggle of news media just rushed toward her. She couldn’t have moved more than ten feet into the auditorium when she was completely surrounded.”

Linda Brinkley, a dietitian who had cared for Stormie in Dallas, watched the local news that evening as the microphones were thrust into Stormie’s face. “It looked like a suffocating situation,” Brinkley says. “Of course, Stormie got more and more withdrawn and finally ended up crying. All she wanted to do was get out of there.”

“Where would you like to go, Stormie?” a reporter asked.

“Home,” she replied.

“Where’s home, Stormie?” another asked.

“Texas.”

“Stormie, what do you think of all this?”

“Awful.”

There were more press conferences, of course, and more tears. Anonymous when they arrived in Pittsburgh, Stormie and her mother were celebrities when they left five months later. But stardom took its toll on the family, especially on Misty, who had waited at home. While everyone focused on Stormie’s illness, nine-year-old Misty suffered in silence. In the months before and after the transplant, Misty gained forty pounds. She also struggled with depression. In March Misty flew to Pittsburgh to spend the final month of their stay with her mother and sister. She ended up failing school that year. And when Stormie was deluged with toys from well-meaning people, it bothered Misty so much that Susie had to make a public request that people buy something for her other daughter as well.

Back in Texas, Stormie became the focus of intense scientific research. Under Bilheimer’s care, she became a patient in the General Clinical Research Center in Dallas. The GCRC is a quiet adult unit located on the seventh floor of Parkland Memorial Hospital. With only eleven beds, it is not the sort of place for a bouncy, impatient six-year-old. For six weeks, Stormie’s heart and liver functions were monitored continually, and she was confined to a low-sodium, low-cholesterol diet. Everything that went into her body was carefully measured as was everything that came out.

Stormie was also heavily medicated with cyclosporine and steroids. Immunosuppressives are highly toxic, with unpleasant and often debilitating side effects. Cyclosporine caused Stormie’s gums to swell and grow down over her teeth. Steroids inflated her body, made her face, fingers, and toes swollen, and produced long hairs on her arms, legs, and back, which embarrassed her. Other drugs produced stomach cramps, achy bones, sore throats, dizziness, headaches, and mood swings.

At first Stormie found escape in riding a red battery-operated motorcycle down to the second floor via the elevator, through the medical school, and out to the open-air plaza. But the doctors soon decided that she was getting overheated, so the scooter was banned. “It was very difficult for a child to spend six weeks in this little-bitty place,” says Ann Harrell, a medical school spokesperson. “You can only watch cartoons and color so much.” Stormie and her mom spent much of their time dodging the media. Stormie would answer the phone in her room by asking, “Is this one of those reporters?” If the answer was yes, she’d slam down the receiver. On May 31, Stormie celebrated her seventh birthday at the clinic. A giant bunny brought her a cake, but she had to eat sugarless-gelatin cartoon characters instead.

Any notion that the new organs would solve Stormie’s problems proved unrealistic. A new organ is not like a new engine in a car. In effect, Stormie became a permanent patient, subject to the rigors of the transplant regimen, forever grappling with the threat of rejection, the daily medications and their side effects, the infections, the physical limitations, the emotional hardship. From the beginning, Susie understood there were no guarantees. When reporters would ask about Stormie’s life expectancy, the doctors would cagily reply, “We would hope to measure it in decades.”

Bit by bit, Stormie reconciled herself to the medical experience. Instead of whining, she adopted a stoic, almost nonchalant attitude about her illness. If a visitor asked, she would casually hike up her T-shirt to reveal the crisscross of scars running across her chest like railroad tracks. She quickly picked up the hospital lingo and knew the names of all her drugs, even when she was taking nine at a time. “These are my xanthomas,” she would say wisely, if anyone inquired about the lumps under her skin. ”But they’re getting littler.”

And indeed they were. Within days of the transplant, the lumps began not only to flatten but to change from yellow to pink. Thirty days after her transplant, the cholesterol level in her bloodstream was leveling off at about 300—one-fourth its former level—confirming all the laboratory theories. Six months after the double transplant, Bilheimer estimated that 63 percent of Stormie’s normal receptor activity was restored by replacing her liver. Later, when she was also given cholesterol-lowering medication, her cholesterol dropped to about 190.

Stormie’s doctors got good mileage out of their work. Results from the double transplant were published in the esteemed British medical journal the Lancet, among others. So successful was Stormie’s heart-liver transplant that Starzl wanted to try again. But he would not be able to repeat his initial success. In November 1984 a two-year-old Alabama girl died shortly after her combined heart and liver transplant. Four months later, seventeen-year-old Mary Cheatham of Dallas—who suffered from the same disease as Stormie—died on the operating table after receiving two heart-liver transplants in two days. Starzl had directed both operations. Overcome with what he called collective depression, he decided to give up combined transplants. “It may be too much at one time,” he told a reporter. “We may have just gotten away with a lot with Stormie.”

Stormie’s illness sent Susie on a frustrating foray into a medical system that was often unfathomable and indifferent to her family’s needs. As a single working mother, she had always scraped by on low-paying jobs. But during the months before the transplant, and in the years afterward, Susie couldn’t work. Taking care of Stormie was a full-time job. Welfare became her only source of steady income. Susie got $180 a month in food stamps and another $80 in AFDC. While Susie never saw a bill for the transplant itself, there were many other bills that she was expected to pay. Medications were expensive. A bottle of cyclosporine, which lasted about three weeks, cost $365. Stormie’s blood was drawn weekly so that her enzyme levels could be checked for signs of rejection, another $350.

After the stay at the GCRC, Susie found an apartment in suburban Garland, to be closer to the hospital. The first of many community fundraisers was held in Cumby at the cafe where Susie had worked. But the donations were never enough. Whenever word got out that the family needed assistance, the public responded with warmth, if not practicality. Stormie left the Pittsburgh hospital in the spring of 1984 with nine bags of toys. But the following December, Susie didn’t have enough money to buy a Christmas tree. An article appeared in a Dallas newspaper, and the next day they had five.

For a while there was not even money for rent, and Susie and the girls lived like transients, camping out with relatives or friends. In Texas, a state with a poor social support system, there is no agency to help a family burdened by costly experimental medical treatment. Time and again Susie tried to find assistance through various state agencies or charitable organizations, but was turned down. She called churches, with no more luck. “I was dumbfounded,” she says. ”I thought I was a good Christian person. I was at the point where I could have sold candy bars on the street corner.” What she needed was someone to shepherd her through the medical system, help her manipulate the game she liked to call “ring around the medical bush.” Susie even thought of giving Stormie up for adoption. “I knew that things were getting to the point where I couldn’t take care of her,” she says.

In 1986 Susie was married to a man who worked in telephone sales, but the marriage only lasted six months. He spent much of his time playing guitar in a rock band. “I just saw no future in it,” Susie says. That summer, she moved her daughters to a friend’s apartment in Mesquite. Also sharing the place was a skinny 23-year-old former Air Force mechanic who was working as a pizza deliveryman. Five years younger than Susie, Alan Purcell took her and the girls skating, to the movies, out for ice cream. The next spring, he and Susie were married. In the fall of 1987 he took a job as an inspector on the F-16 at the General Dynamics plant in White Settlement, a blue-collar community on the western edge of Fort Worth, and Stormie started fifth grade at North Elementary School. On Alan’s salary, the family moved into a modest house half a mile from the plant. General Dynamics’ health maintenance organization covered 80 percent of Stormie’s medical bills. Susie got a full-time job in a pharmacy. Stormie, who loved animals, got a pet Doberman and two rabbits.

Stormie gained four and a half years of relatively good health from her historic operation. Then, in September 1988, a blood test showed that her enzyme levels were elevated, indicating that something was wrong with her liver. Stormie was hospitalized for four weeks in Dallas while doctors fiddled with her medications. “She’d done real well, and all of a sudden she had to be hospitalized again, and she was bummed about being there,” recalls social worker Kate Petrik. But it was during that stay in the hospital that Stormie found a friend: fourteen-year-old Ronney Courtney, a fellow liver recipient with a Prince Valiant haircut and a face swollen from steroids. Stormie and Ronney did everything together—riding up and down the elevators, exploring the hospital basement, wandering outside to the park across the street—while attached to their IV poles.

In late October, after no improvement, Stormie flew to Pittsburgh for more tests. Starzl determined that her system wasn’t absorbing enough cyclosporine and identified a small blockage in her bile duct as the culprit. In a five-hour operation, he removed the obstruction. But later blood tests showed that the problem hadn’t gone away. Susie quit her job. Stormie got a homebound teacher. And they spent the next year traveling back and forth to the hospital for blood tests. When Stormie needed to be in Pittsburgh on short notice, Susie would beg the airlines for free tickets.

In November 1989 Stormie became weak and jaundiced, a sign that her liver was failing. In Pittsburgh, Starzl decided she was experiencing liver rejection. This time, he tried something new. He took her off cyclosporine and prescribed a controversial anti-rejection drug called FK-506. Discovered in a fungus on a mountainside in Japan, FK-506 had been approved for use only in Pittsburgh. Like cyclosporine, it inhibits the T-cells that attack foreign organ tissues. But unlike cyclosporine, it doesn’t cause the same debilitating side effects. There was another unexpected benefit from the switch. As an experimental drug, FK-506 was provided free.

December and January were particularly bad months for Stormie. She was tired and headachy, and she itched all over. Her teacher, Fay Presswood, remembers Stormie more than once going to the bathroom and throwing up. Tests showed that the FK-506 was fighting the rejection, but they also unmasked an underlying problem: hepatitis. Doctors suspected that the virus had been floating around in her system since the transplant. Stormie knew the only solution was another transplant. “I’m sick of this old liver,” she would say. “I wish they’d put a zipper in so they could take one out and put one in whenever they need to.” On February 14, exactly six years since her double transplant, Susie got a call from Pittsburgh that a new organ was available. That week, in a ten-hour operation, Stormie received her second transplanted liver. It did not go smoothly. The next day the surgeons opened her up again to reconstruct an artery. Stormie was released within two weeks but was back in Pittsburgh two months later, suffering once again from hepatitis.

Of all the disappointments of the previous years, this was perhaps the crudest. Presswood remembers stopping at the house one day in the winter of 1989 to find Susie on the front lawn, surrounded by piles of household appliances, toys, guns, and fishing gear—even the five-foot stuffed bear that Stormie had carried back and forth to Pittsburgh. Everything was for sale. Stormie had to make an emergency trip to Pittsburgh, and Susie needed cash. In March, under financial strain, the family moved into the Plaza Apartments, a bleak FHA-subsidized complex across the street from General Dynamics. Without a back yard, Stormie had to give up her dog.

No matter how hard she tried to be like other kids, Stormie was never able to lead a life that could be considered normal. Because of her peculiar situation, she came of age poorly equipped to handle the position her illness had thrust upon her. The years of transience and poverty also took a toll. While Alan brought a degree of security to the family, he also introduced fresh tension. Alan was a disciplinarian; Stormie resisted his interference. Eventually, they coexisted only by avoiding each other. Susie once told a reporter that the root of the problem was Stormie’s confusion about her real father, who had disappeared from her life when she was three. Stormie had vivid recurring nightmares in which her father was kidnapping her.

Unlike Misty, who was outgoing and talkative, Stormie was introspective and moody. She loved to read but often chose melancholy books about people who had suffered losses. She wanted to write her own book, an autobiography she would call In the Darkness, about her life, her pets, and the thoughts that passed through her mind as she fell asleep. Sometimes she would talk about the future, about raising a family, becoming a veterinarian. She would talk about the day “when we move to the country” or “when we get our own farm,” says Fay Presswood. “But she always said it a little wistfully, as though she knew it would never happen.” Stormie and her mother frequently talked about death. Stormie understood that another person had to die before she could get her new organs. This intimacy with mortality gave her a sense of gravity that distanced her from other kids her age. “She wasn’t obsessed with it,” Susie says, “but she knew she wasn’t like other people.”

In some ways Stormie was a typical adolescent: chattering on the phone, listening to heavy metal, hanging out at the mall with friends. But often her peers had trouble understanding her indifference to the reporters who relentlessly pressed her for interviews. “Her friends were saying, ‘Go ahead and be a star,’ ” says Susie, “but all she wanted to do was be a veterinarian.” It was as though the constant presence of the media served as a reminder that she wasn’t normal. “Whenever there was any mention of the press, you could see Stormie physically withdraw,” says Pittsburgh pediatrician Basil Zitelli. ”She would physically assume a hunched posture, her head would dip, she’d scowl, like a physical revulsion. She did not like the attention. She did not like the questions. She did not like being different.” Stormie learned to respond to reporters’ questions with tact—when she felt like it. Most of the time she didn’t. One television producer who spent a day with her in the fall of 1990 remembers her as stubborn and contrary. “All day long she was avoiding the camera, sticking out her tongue,” the producer says. “She’d be smiling in real life, then she’d see the camera, and her face would go worse than cold.”

Stormie knew the media had, in desperate times, served as her family’s lifeline to private donations. She understood the media’s role in educating the public about organ transplants. But she also understood a deeper family truth: that her mother had come to appreciate the attention of journalists and even cultivated their friendship. Often she was the one who would call reporters and update them on Stormie’s condition. Perhaps that was Susie’s way of sharing the burden. Susie liked to say that Stormie was not just her daughter—Stormie belonged to the world. But this was not Stormie’s concept of herself. Stormie wanted the world to leave her alone.

Countless articles and television news stories portrayed Stormie in glowing, saccharine terms. She became a caricature of youthful innocence. She was, it was said, a “shy child,” one who “dodged cameras” and “did not want to be the center of attention.” But no one wanted to suggest that all of that unwanted scrutiny by the media was not healthy for Stormie, that frankly, she would have been a lot happier without it. Perhaps the media had too much invested in the mythical Stormie to portray her realistically. Perhaps, too, an element of guilt was at work, for if Stormie became angry and resentful in the presence of reporters, it was certainly at least partly the reporters’ own fault. “There was a sense of responsibility,” says one, “as in, did we create this monster?” As Stormie got older, reporters expected her to become more articulate. Instead, she was less so. “How do you feel, Stormie?” they asked as she stepped off the airplane, looking lousy. “How do you expect me to feel?” she snapped back.

The new liver never completely stabilized. By March, Stormie’s enzyme count was once again elevated. Back in Pittsburgh, doctors increased her dosage of FK-506. Then in May, her hepatitis flared up. This time the doctors put her on alpha interferon, another experimental drug that had the unfortunate side effect of boosting the body’s immune system. But the doctors had no choice; the hepatitis was life-threatening. Now they were engaged in a perilous juggling game, playing off the theoretical benefits of medications against their side effects. “It’s almost like walking through a land-mine area,” says pediatrician Zitelli. “You inch along, feeling your way, always cognizant of the possibility that something might blow up in your face.”

In the end, that was exactly what happened. When Stormie arrived at the Pittsburgh hospital at around one in the morning on November 11, her heart was enlarged and there was fluid in her lungs, both indications of heart failure. Stormie’s hands and feet were cold, and her nails were blue, signs of poor circulation. At about two-thirty, according to the autopsy, “she complained of shortness of breath and was found to be in a state of confusion; she was combative and demonstrated inappropriate speech.” By six, her blood pressure had dropped and she asked for a glass of water. Two hours later, while undergoing tests, Stormie’s condition rapidly worsened. Just as the doctors decided to transfer her to intensive care, she went into cardiac arrest. For an hour they tried frantically to resuscitate Stormie: they gave her various medications, they applied chest compressions, they even attempted to insert an artificial pacemaker by threading tiny wires through a vessel into the heart. Nothing worked. The heart refused to beat.

Doctors don’t know why Stormie’s body rejected her heart. All along, Starzl and his associates had assumed it was the liver that posed the biggest threat. Her heart, they thought, was safe. In November 1989, less than a year before her death, Stormie had undergone a routine heart biopsy and a coronary angiogram, and both indicated that everything was normal. Though they are not sure why, doctors think that in some way the immunological dynamics of her system veered off balance, leaving her heart defenseless.

No one would hesitate to say that as a medical experiment, Stormie Jones was a dazzling success. Starzl’s groundbreaking surgery validated laboratory theories about cholesterol metabolism and doubled Stormie’s life span, giving her more than six years in which she lived a reasonably active life and reached the threshold of adulthood. In assessing what had been accomplished and what had failed, the doctors often note as a point of pride that Stormie died not from the cholesterol imbalance that had threatened to kill her at age six, but from complications arising from her transplants. Yet there is also a cruel irony at work. For even though Stormie can be considered a success, the moment that she died she also became something else. She became a symbol of the limitations of medical science. “Anytime a child dies, particularly when they seem to have been doing well, it always puts us in a terrible quandary,” says Zitelli. “How could we have picked this up sooner? What should we have done different? Where did we fail?”

By early February 1991, Susie Purcell was ready for a new life. She was sick of living in the dingy apartment across the street from General Dynamics. For two weeks in early January, the hot water went off. Then, while the boiler was being replaced, there was no water at all. The refrigerator door was broken. So was the oven. “We can do better than this,” Susie said. “Before, we couldn’t afford it. But we don’t have to live like this anymore.” Stormie had always wanted a place in the country, but because of her illness, she had needed to be near a hospital. Now Susie and Alan were thinking about finding a mobile home near Lake Granbury.

In Stormie’s absence, Susie focused her attention on Misty. Finally, after years of complaining about horrendous stomach pain, Misty’s condition had been diagnosed—she had ulcers. Last summer Misty, almost sixteen, married her longtime boyfriend, a twenty-year-old drugstore clerk. Two months later, she was pregnant. Stormie had been thrilled at the prospect of being an aunt. Now Misty was hoping that her baby would be a girl.

Susie was still getting bills for Stormie’s medical care, which she kept in a heavy file box. She pulled one out at random—a bill for $2,890 from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for “pharmacy, lab services, nursing department, and supplies.” Another, for weekly blood work, was for $354. Yet another was from the University Pediatric Association, for $4,694.

Then Susie brought out a copy of Stormie’s thirteen-page autopsy, which she had recently received from Pittsburgh. It was filled with difficult medical terminology. In the margins were notes made in Susie’s childish, loopy handwriting, explanations of troublesome words she had looked up in her medical dictionary. Next to “chronic,” she had written “of long duration.” Next to “sclerotic,” she wrote “hardened.” And by “necrosis,” “dead tissue.” Susie said she understood more or less what the autopsy meant—that Stormie was beyond help. “I figure one way or another it would have gotten her,” Susie said. “If the alpha interferon hadn’t gotten her, she would’ve died from the hepatitis. I’m not surprised. In the back of my mind, I always knew that I could wake up one morning and find her dead.”

Five days later, a U-Haul truck pulled up at the Plaza Apartments. Susie and Alan spent several hours loading their possessions, then drove off in the direction of Granbury. They left no forwarding address.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Medicine

- Longreads

- Dallas