This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

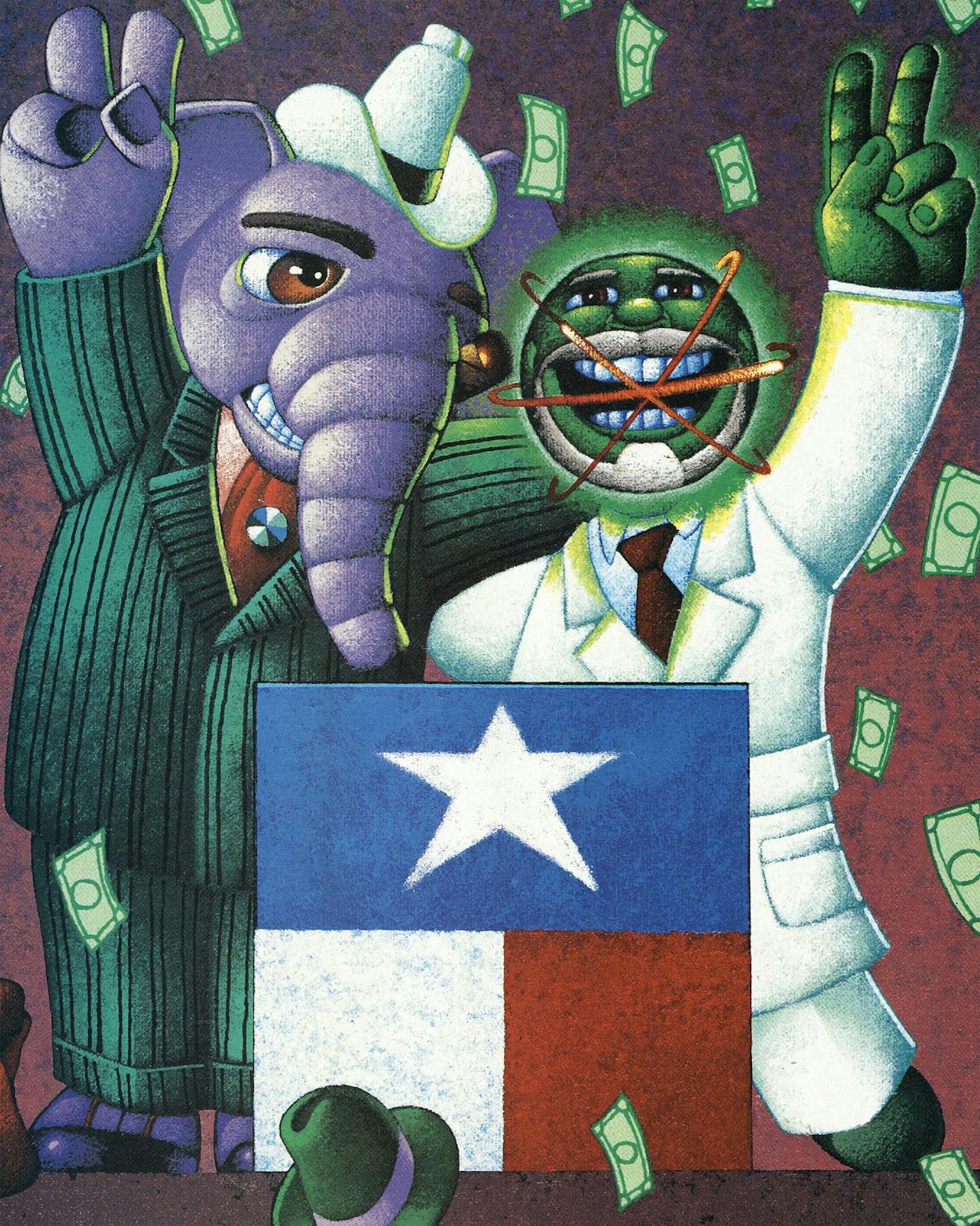

In a state desperate for good news, the announcement by the Reagan administration that Texas had won the competition for the supercollider was greeted as a second Spindletop. The press surrendered all pretense of self-restraint. TEXAS SUPER CHOICE FOR COLLIDER trumpeted the November 11 Dallas Times Herald, which devoted five of its seven front-page stories to the $4.4 billion project. Inside, six more stories followed, accompanied by five charts and an editorial. Not even the immediate protests by sore losers from Arizona to North Carolina that the fix was in could dampen the statewide enthusiasm.

The reasons for all the celebrating are familiar reading by now: thousands of jobs, billions of dollars, and status beyond quantification. Construction alone could employ 14,000 workers. North Texas cement contractors are already calling the collider’s 53-mile circular tunnel the Big Pour. The completed laboratory will require anywhere from 3,500 to 7,000 workers, including more than 2,000 scientists. The supercollider incorporates in a single project all the mantras of Texas in the eighties: economic development, diversification, high tech, and the big leagues of research at long last.

But economic growth is only part of the effect that the supercollider will have on Texas. Even before a dollar has been spent in the state, the landing of the project has changed the course of Texas politics. The campaign for the supercollider marks the reappearance of an enduring Texas theme: that the state must amass political influence to keep from becoming an economic backwater. The proposition is equal parts pork barrel and righteous indignation. While the rest of the country may be convinced that Texas always gets what it wants out of Washington, Texans have long believed just the opposite. Of the nation’s 36 federally funded research and development laboratories, for example, Texas has none.

Texas Republicans, however, have been loath to acknowledge that public money—state or federal—offers a remedy for the state’s problems. Two years ago, remember, Governor Bill Clements was insisting on cuts in the state’s education budget to avoid a tax increase. Yet it was he who orchestrated the supercollider offensive. U.S. senator Phil Gramm takes such a hard line against spending that he has even voted against federal benefits for unemployed oil-field workers. Yet he called the supercollider “the most important scientific project that will be built anywhere in the world in the last quarter of the twentieth century.”

Thanks to the supercollider, the Republicans have a new message to use in the 1990 campaign. It’s really the old message that once belonged to the conservative Democrats: we can deliver for Texas.

Perhaps the state’s Republican leadership has figured out that in order for the GOP to become the preeminent party in Texas, it has to modify its stance. Republicans have to find something to be for. Until now, their message has been entirely negative: against spending, against taxes. They have taken Ronald Reagan’s 1980 perception of America—a rich nation whose economy didn’t reach its potential because the government taxed, spent, and regulated too much—and misapplied it to Texas, where the per capita income is below the national average and where state taxes, spending, and regulation remain low. Now the Reagan era is at an end, a Texan (if somewhat ersatz) is about to occupy the White House, and thanks to the supercollider, the Republicans have a new message to use in the 1990 campaign. It’s really the old message that once was the exclusive property of conservative Democrats: we can deliver for Texas.

Of course, the supercollider is a long way from delivered. Congress still has to put up the money, and the timing could hardly be worse. The supercollider arrives on Congress’ doorstep at the same time that the Gramm-Rudman deficit-reduction schedule requires a $30 billion cut in the federal budget. Since George Bush has apparently ruled out a tax increase, money for the supercollider must come from additional cuts.

The politics could hardly be worse either. In the House, the fate of the supercollider rests with the Energy and Water Subcommittee of the Appropriations Committee. Its staff is known to be hostile to the supercollider. Moreover, the funding for NASA also comes through Appropriations, and there is certain to be jealous grumbling—or, worse, an attempt to rob Peter to pay Paul—because Texas has two science plums. Make that three: Sematech, an Austin high-tech consortium, gets federal money too.

Texas, however, is not without weapons of its own—House Speaker Jim Wright and Senate Finance Committee chairman Lloyd Bentsen. Less than a month after the awarding of the supercollider to Texas, Wright began maneuvering to get a Texan on the crucial Energy and Water Subcommittee. A seat on Appropriations became vacant when a Florida congressman lost his reelection race in November. Ordinarily the seat would be filled by another Democrat from the Southeastern region, but Wright wanted Jim Chapman of Sulphur Springs to fill the vacancy. His choice has been ratified by a Democratic steering committee and needs only the approval of the House Democratic caucus in January to become official. Bentsen demonstrated that his insider’s skills had not grown rusty during his vice-presidential campaign when he backed Louisiana senator J. Bennett Johnston’s bid for majority leader; Johnston lost, which means that he remains (1) chairman of the subcommittee that will handle the supercollider and (2) indebted to Bentsen.

Whatever happens in 1989, the battle over funding is likely to continue for several years. Both of the Texas Democratic congressmen currently on the full appropriations Committee, Ron Coleman of El Paso and Charlie Wilson of Lufkin, expect that the supercollider will get at least as much money as last year (around $100 million); neither expects to get enough to begin construction (around $600 million). Once the Big Pour begins, the supercollider is secure; until construction begins, it remains in peril.

The one thing that is certain is that opponents of the supercollider will continue to insist that Texas won because of political influence. Forget for now the fact that Texas had a substantial lead over the six other finalists in the rating system used by the Department of Energy. The proper response is: “Sure. So what?” The ability to get things done in government is nothing to be embarrassed about. For the supercollider to become reality, one state is going to have to go into battle alone, not only against jealous politicians but against jealous scientists as well, all of whom see the supercollider as a threat to their own pet projects. If, as the Reagan administration obviously believes, the supercollider is essential to the future of the country, should its fate be entrusted to Arizona? to Colorado? to Tennessee? to North Carolina? Why not to Texas, a state where both Republicans and Democrats understand the importance of political influence and aren’t ashamed to use it? “I guarantee you,” says Charlie Wilson, “that the supercollider would never be funded if it had gone to any other state.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics