This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

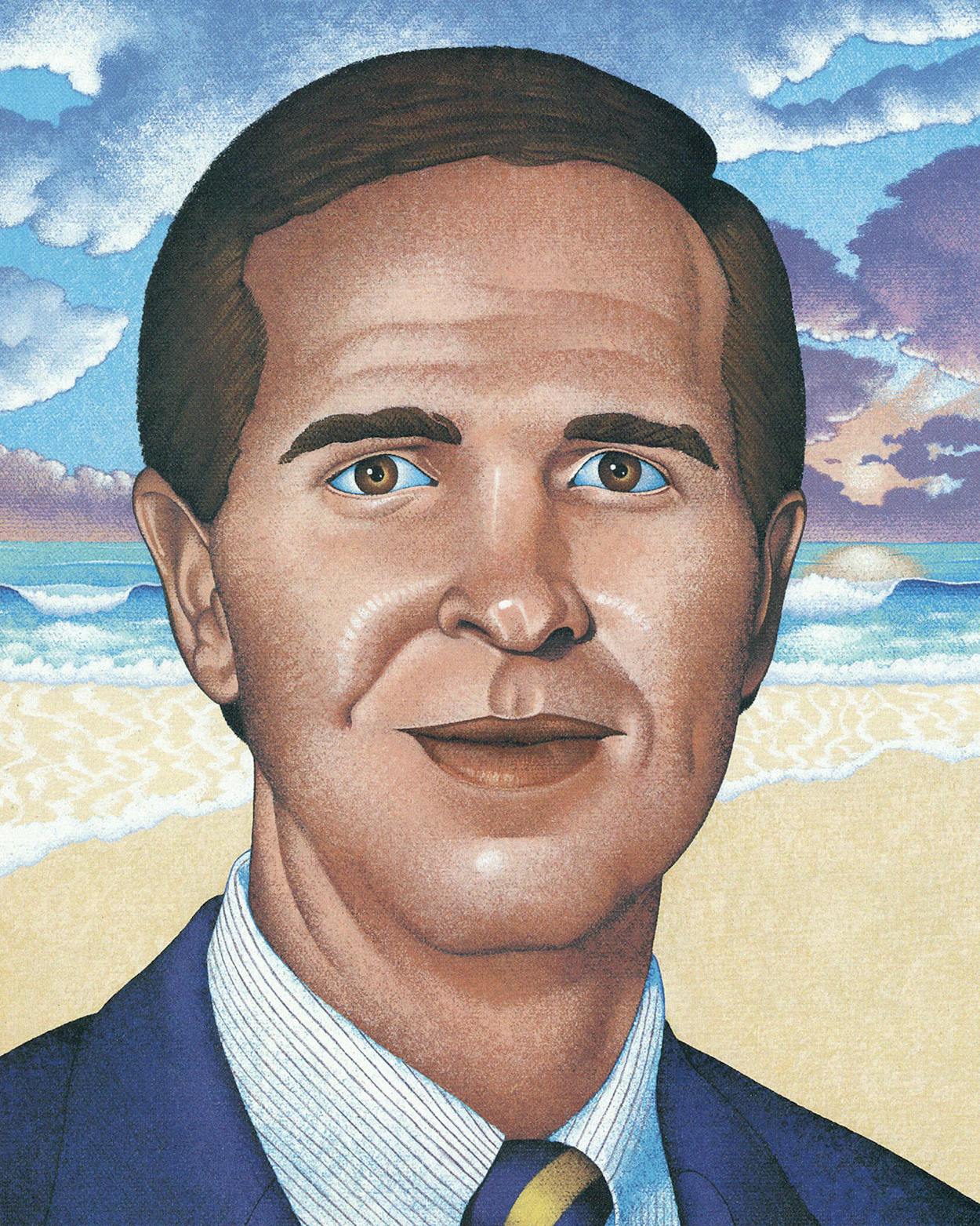

“This is the future of Corpus Christi,” says Robert Rowling, gesturing toward blocks of land near the city’s oceanfront convention center, home to only grass and windblown palm trees. For 39-year-old Rowling, his lanky frame folded behind the steering wheel of his burgundy Mercedes and his deep-set brown eyes shielded by black wraparound Vuarnet sunglasses, this isn’t an idle prediction. Together with his father, Reese, he owns an estimated 30 percent of the downtown land in this coastal city.

Ten years ago the pair were unknown oil and gas independents who had just sold their interest in Live Oak County’s East Chapa field. Reese, a geologist, and Robert, a Southern Methodist law school grad running the family’s Tana Oil and Gas, had cash in the bank but a business based on an industry that was in steep decline. Though hordes of oilmen were cutting back or going broke, the Rowlings saw opportunity. Tana Oil and Gas was debt-free, a position that allowed the company to take advantage of cheaper costs for leases and drilling. Tana began drilling in Hildalgo County, and by 1987, gas discoveries had vaulted it into one of the nation’s top producers. But for the Rowlings, the oil and gas business had subtly changed—from the thrill of wildcatting to the mundane managing of wells. Tana hung out the For Sale sign, selling its producing properties to Texaco in 1989 for $476.5 million in cash and stock.

“Now that we’ve got some assets to work with, it’s a whole new challenge trying to deploy them properly,” says Robert. Since the Texaco purchase, the Rowlings have embarked on an epic spending spree, again using devalued markets and a cash-strapped economy to their advantage. Lured by a still-weak oil and gas climate in 1990, Tana Oil and Gas began replacing producing properties, pumping more than $50 million into exploration over the next three years. They bought a controlling interest in the Corpus Christi National Bank from bankrupt MCorp. In the past 22 months, the Rowlings have entered the hotel industry, buying six Texas hotels and Arizona’s Tucson National Golf and Conference Resort for a bargain-basement $100 million. “We got in at a real good time,” says Robert. “If I had it to do over again, I would have invested twice as much.” But Corpus Christi’s bayfront Marriott and Sheraton turned into more than just good investments. They became the linchpin in the Rowlings’ plan to revitalize the city.

The Rowlings know Corpus Christi well. It has been home since 1960, when Reese’s oil company employer transferred him there from El Paso. A year later he lost his job, an event Robert still remembers clearly. He has painful memories of his parents’ worrying over the dinner table about paying the bills and of the treatment he received as a teenager. “We were from the wrong side of the tracks, and my nose was rubbed in it,” he recalls. The lure of a free education prompted Robert to enter the U.S. Air Force Academy after high school, but the stint was short. Reese’s wildcat wells started hitting, and Robert left the academy for the University of Texas, then SMU.

While his father still spends his days as an oilman, Robert spends at least half of his time managing the real estate holdings and hotel operations. “It’s like running a small city,” he says. “It never shuts down.” Entire city blocks the Rowlings bought years ago are being cleared of abandoned commercial buildings, not to make room for any imminent construction but, for the moment, simply to get rid of eyesores.

“Corpus can be a much neater place than it is,” Robert says. “The money hasn’t been invested to make Corpus meet its potential.” He was involved in bringing the aircraft carrier Lexington to Corpus Christi as a permanent tourist attraction. “It’s a big hit,” he says of the ship. “Attendance is so far above predictions it’s ridiculous.” Yet the success of the Lexington is not really enough to satisfy Robert. “We’ve made some progress, but not as much as I would want,” Robert says. And he is the first to admit that his civic activities have a business purpose. “We’re in Corpus Christi because we can make money here,” says Robert. “It’s not altruistic.”

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Corpus Christi