This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In 1966, during a visit to Dallas, the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was asked if anything he saw reminded him of the old days of the American West. Oh, definitely, he replied, and then he recounted his attempt to order vodka at a local restaurant. A waiter informed him that it was against the law. So did the hostess. But a busboy tipped him off to the location of a nearby package store. Yevtushenko slipped out unobserved, returned with a bottle concealed under his jacket, secreted it under the table, and stealthily poured the contents into his tomato juice. It was, the poet said, the greatest adventure of his trip; he fully expected to be arrested at any moment.

The ban on liquor by the drink remained in force until late 1971—less than a dozen years ago, a blink in time. In much of Texas it is still the law today. Yet the scene Yevtushenko described seems like something out of the distant past—as indeed it was, for there are two ways of measuring the passage of time: by the calendar and by change in circumstance. Seldom has any peacetime society changed so much, so fast, as Texas at the beginning of the great boom—the watershed years of the early seventies. Consider these developments, none of which was even foreseen when the seventies began:

- liquor by the drink

- the Sharpstown scandal

- the OPEC embargo

- Shell Oil’s relocation from New York to Houston

- the Houston Galleria

- the demise of the Citizens Charter Association in Dallas

- bank holding companies

- the purchase of the Dallas Times Herald by the Times Mirror Company, owner of the Los Angeles Times

- the introduction of the hand calculator by Texas Instruments

- Southwest Airlines

Within three years these ten factors transfigured Texas as dramatically as gold transfigured California. By 1973, year one of modern Texas, the state was a completely different place.

The changes of the early seventies were different from the landmark events of previous decades, the effects of which were far less explosive. The postwar forties brought residential air conditioning and oil’s supplanting of agriculture as the state’s chief industry. The fifties brought freeways, natural gas, and petrochemicals; the sixties, NASA, the Astrodome, NorthPark in Dallas, a Texan in the White House, and the great national upheavals that touched the state. Yet in fundamental ways Texas wasn’t changing at all. Relative to the rest of the country, Texas was still a poor state—and getting poorer. Per capita personal income had been 93 per cent of the national average in 1949; by 1956 it was down to 89 per cent, and by 1965 it had dropped still more, to 85 per cent. (In 1980 Texas reached the national average for the first time ever.) Population increase in the sixties fell off by a third compared to the fifties—the second-lowest growth rate in the state’s history. (The seventies’ growth rate was the highest since Spindletop.)

Just as important were some things that can’t be measured. The soul of Texas had scarcely changed in a quarter of a century. As the seventies began, the most popular restaurants still were steakhouses and the most prominent symbol of an evening’s entertainment was the brown paper bag. The world price of oil was effectively set by the Railroad Commission through its limitations on production. The state was governed by one political party, whose leaders did pretty much as they pleased. The cities were run by local oligarchies, who did exactly as they pleased. Their pleasures invariably received the enthusiastic and unquestioning support of the state’s newspapers. The list of the state’s twenty largest companies was loaded with non-industrial businesses like J. Weingarten supermarkets, Campbell Taggart bakeries, and T.I.M.E.-DC trucking. Transportation between the state’s major cities was mostly by automobile; there were almost no flights at off-peak hours, and shrewd travelers perused schedules carefully, lest they end up on a milk run like the flight that made two stops between Dallas and Austin. Shoppers on the cutting edge of fashion had three choices—Neiman’s, Sakowitz, and New York. Businessmen seeking capital had only New York, because no bank in Texas had the money to stake a major deal.

The best appraisal of Texas before 1973 is a book by John Bainbridge, The Super-Americans, published in 1961 and based on a series of articles in the New Yorker. The title refers to the state’s oil millionaires, but the book ventures far beyond that fraternity to portray the entire culture that was Texas—an unsophisticated society pregnant with boosterism, prone to equate bigness with greatness, and obsessed with the outside world’s failure to recognize its rightful place at the apex of American civilization. The late Dallas literary critic Lon Tinkle, writing in 1971, declared that Bainbridge’s Texas had hardly changed in any meaningful way.

If, in the early seventies, one read that book to understand how much Texas had remained the same, today one reads it to understand how much Texas has changed. By 1973 John Bainbridge’s Texas had mutated beyond recognition: social life, politics, business, finance, transportation, energy, even the cast of characters were different. Lyndon Johnson died and Ben Barnes, whom LBJ had anointed as a protégé worthy of the White House, was expunged from politics. John Connally switched parties. The three mayors who had dominated Texas’ largest cities in the sixties—Louie Welch of Houston, Erik Jonsson of Dallas, Walter McAllister of San Antonio—were out of office, and the organizations that had elected them were in ruins. Frank Erwin’s long reign as czar of the University of Texas ended. The draconian Texas drug law—up to life in prison for possession of marijuana—was rewritten. Natural gas was curtailed, and its price quadrupled before anyone had ever heard of OPEC. Even the arts, always the last aspect of a culture to reach maturity, began to show signs of life: the state’s most ambitious museum, the Kimbell, opened in Fort Worth, and David Gockley arrived to lead the Houston Grand Opera. This flood of change, fed by the great events of the period, cut three channels through Texas’ cultural landscape—channels that define the present and sever Texas from its past. These are the end of economic colonialism, the growing sophistication of our society, and the demise of the old political oligarchy.

On the far western edge of Houston, just as it seems that the coastal plain is about to reclaim the land from concrete, an immense office development sprouts up from the open prairie. Park 10, as it is known, stretches for three miles along Interstate 10 outside the Houston city limits. Surrounded by 26,000 acres of empty reservoirs, the development so far consists of 44 office buildings and perhaps a few more forlorn trees. In one of the buildings, an unremarkable six-story glass box set a quarter-mile in from the freeway, the first five floors are occupied by a company called Hyundai, a worldwide South Korean engineering firm whose Houston office designs offshore drilling platforms. Not for Texas—for Saudi Arabia.

The presence of a company like Hyundai in Houston illustrates just how far Texas has come since 1973. Though until 1958 Texas produced more oil than any country in the world, Texas oil, like all the state’s resources, for years remained primarily a chattel of New York. The major oil companies kept their headquarters in the East, borrowed their money in the East, paid big salaries in the East, and ran their international operations from the East. Before Shell moved to Houston in 1972, only six of the state’s twenty biggest companies were energy-related; now only five are not. Houston has shoved New York aside to become the center of the international oil business: Hyundai is there because Aramco, the Arabian-American oil consortium that has the Saudi drilling concession, is there, and Aramco is there because most of the majors are there, with either corporate or operations headquarters. Shell was the big prize. The impact was partly financial (Shell immediately became the largest company in the state) and partly psychological (Texas was a colony of Manhattan no more).

The idea that Texas could be a colonial outpost of the East seems archaic today, but before 1973 it was a staple of Texas political and economic discussion. Texas was in the classic colonial predicament: it exported raw materials and imported finished goods. We led the nation in cotton production but sent the cotton to the East to be turned into denim and then reimported the denim so that our cheap labor could make it into clothing. We led the nation in cattle raising but imported leather shoes and belts and purses. We were a leader in grain sorghum but shipped our livestock and grain to Midwestern fattening yards and then imported beef.

Occasionally the resentment toward New York spilled over into politics. Furious over seeing Texas capital sucked out of the state, the Legislature in 1907 required any insurance company doing business here to invest three quarters of its Texas premium income inside the state. Out-of-state companies responded by leaving, and that was the genesis of the state’s robust insurance industry. Pappy O’Daniel used the theme that Texas was a colony of New York in his gubernatorial campaigns. A later governor, Allan Shivers (1949–57), still gets irate when he recalls battles over railroad freight rates; it cost more to ship the same product from Texas to New York than from New York to Texas.

Industrial expansion thus became a holy cause to the state’s business community. E. B. Germany, president of one of Texas’ two early steel plants, urged that every high school teach a course on the importance of industry to the state. But Texas was too poor to be an industrial center—less than $10 billion in bank deposits in the entire state as late as 1955, compared with $110 billion today. When Prudential Insurance made a nine-figure loan to Lone Star Gas in 1952, Republic National Bank of Dallas hosted a reception in honor of the unprecedented event and the state’s newspapers carried the joyful news on their front pages. The expansionist zeal carried over into the political world, where advocates of attracting industry resolutely opposed anything that they thought might cloud the business climate—taxes, unions, industrial safety laws, liberals.

Another aspect of that era that now seems light years away is the hoopla that surrounded the Texas Industrial Commission, a state agency given new life in 1958 to recruit industry. In the commission’s early years a seat on its board was as prestigious as a seat on the UT Board of Regents. Among its missions was to co-host an annual conference on industrial expansion, where the governor himself would hand out plaques—“Congratulations to Temple Industries on its new fiberboard plant”—to companies that had made capital investments during the previous year. These elaborate ceremonies lasted into the early seventies, when the state’s economic growth became so phenomenal that such blandishments were utterly superfluous. In the sixties Texas added fewer than two thousand new manufacturing plants; between 1970 and 1977 it added almost six thousand.

Two other developments of the period hastened the demise of Texas’ colonial status. New federal legislation encouraged the larger Texas banks to circumvent state restrictions on branch banking by stringing together smaller banks into a single system. By pooling the resources of all the banks owned by the holding company, banks like InterFirst and RepublicBank in Dallas and First City and Texas Commerce in Houston accumulated capital and could make loans in sums undreamed of just a few years before. When Raymond Nasher built NorthPark in the mid-sixties, InterFirst (then First National) could lend but $6 million of the $18 million project; for the rest, Nasher had to turn to the East. Today 4 Texas holding companies are among the nation’s 25 largest banking concerns. They can handle nine-digit loans without Eastern help. The old colonial process has been reversed: Chase Manhattan, Morgan Guaranty, Manufacturers Hanover, Citibank, and Chemical have come to Texas to compete for loans, along with dozens of foreign banks—32 in Houston alone.

Texas Instruments’ hand calculator also helped break the colonial pattern. Electronics provided Texas for the first time with an industrial base that did not require depleting the state’s own resources. The calculator freed the electronics industry from its dependence on defense contracts and decisions made in Washington. In the seventies TI opened six plants; by the eighties Atari was making Pac-Man cassettes in El Paso.

For the present, though, there is still nothing like oil. The energy crisis that followed the OPEC embargo at first was considered a disaster for Texas. People predicted the end of fossil fuels and, therefore, of the Texas oil industry. Instead, the immediate fourfold increase in the price of Texas’ basic raw material turned out to be a bonanza. The shock of the embargo forced the federal government to raise the controlled prices for both oil and gas, and the results are visible all over Texas. The gross state product increased by 7.9 per cent in 1977 and by another 6.7 per cent in 1978—numbers unheard of for an economy that was healthy to begin with. Gas boomed even more than oil: in 1970 only two gas companies were on the list of Texas’ twenty largest companies, but by 1982 there were eight.

Nowhere was the change more striking than in Houston. In 1972 downtown Houston was said to be overbuilt with 12 million square feet of office space. Today there are 50 million. In the early seventies the intersection of Texas Highway 6 and Farm Road 529 in Northwest Houston was still known as Wolf Corners, because bounty hunters trapped predators and hung their hides on the fences by the rice fields. Today it is part of suburban Houston, a short drive from Hyundai, another testament to what oil means to Texas.

The first time tourists visited Texas in any great numbers was in 1936, when the state celebrated its centennial. Because the state constitution then contained what was known as the Carpetbagger Clause, which prohibited the expenditure of any public funds to attract outsiders, promotion was limited to the construction of tourist bureaus where major highways entered the state. The booths, staffed with Texas A&M cadets, were so successful that they spawned the original Aggie joke—folks said the Aggies so confused visitors that they couldn’t find their way out again. But by 1964 tourism had dropped off so badly that Governor John Connally invited a group of writers from major out-of-state travel magazines and newspapers to tour Texas at state expense. So eager was Connally to promote tourism that he met the writers in San Antonio and took them to his ranch near Floresville, where he spent the evening praising underappreciated places like Lubbock.

The sad lot of Texas tourism typified the social isolation that used to be characteristic of the state. Texas ranked twenty-third in the country in revenue from travel when Connally set up his tour and actually took in fewer dollars than it had five years earlier. Today Texas stands third in convention and tourist revenues; in 1980 the industry produced more money than agriculture. The social maturation of Texas has had as much influence on the state as the end of economic colonialism. It is a change that is reflected in vast differences in entertainment, marketing, travel, and self-criticism that grew out of the events around 1973: liquor by the drink, the Galleria, Southwest Airlines, and the purchase of the Dallas Times Herald.

To gauge the impact of liquor by the drink, it is necessary only to compare the hotel and restaurant businesses today with what they were before 1973. Back in the sixties, representatives of the Stouffer Hotels chain visited Dallas to discuss constructing a large hotel close to where Texas Stadium is today. When the deal was nearly clinched, the visitors and their Dallas developer met with a representative of the old Liquor Control Board. The agent assured them they’d have no trouble with the law if they’d just follow a few simple rules for private clubs; then he launched into a discussion of paperwork and arcane guidelines that caused Stouffer to cancel the deal as quickly as if the interest rate had doubled.

The reason hoteliers and restaurateurs love liquor is that it pays. In a typical $2.50 drink, the liquor and taxes account for around 75 cents. For each $60 worth of food it sells, an expensive restaurant-bar like the new Quorum in Austin will gross $40 in drinks—and net most of its profit. Hotels are more complicated economic creatures, but even when the occupancy rates are down, their bars always seem to be full. Liquor provides the profit margin to sustain first-rate hotels and restaurants; that is why Texas had so few of either when liquor was illegal. No major hotel was built in Houston between the Shamrock in 1949 and the downtown Sheraton in 1962; today new ones claiming world rank are opening every year—the Inn on the Park, the Warwick Post Oak, the Remington. As for restaurants, well, Texans spent years fuming over the malediction pronounced on their beloved steakhouses by a food writer in Holiday magazine: the beef, he wrote, had “a curious pink pallor and a lack of flavor. [It] tastes as if it were a porous fiber from which, by chewing, you obtain a flavored liquid—not the taste of meat or soup.” It was next to impossible to get seafood, and if you somehow succeeded, what you got was invariably fried. As for sauces, if you weren’t eating barbecue, forget it.

A list of Texas’ most celebrated restaurants in the early sixties is a period piece. The Zodiac Room at Neiman-Marcus in downtown Dallas was renowned for offering dishes from a different foreign country during each of the store’s annual Fortnight promotions. Aside from three familiar names—the Old Warsaw in Dallas, Maxim’s in Houston, La Louisiane in San Antonio—the rest were steakhouses like Houston’s Ye Old College Inn and Bud Bigelow’s, and Dallas’ Town and Country and Cattlemen’s. One of the big names in Austin was the Barn, a steakhouse noted for its atmosphere, which consisted of a simulated hayloft and a tape recording, replayed regularly, of cocks crowing, cattle lowing, and other barnyard sounds. The College Inn made its reputation by being the first place in Houston to offer cheese and bacon bits with a baked potato. With liquor by the drink, restaurants could afford to fly in Pacific salmon and to pay chefs with names like Jacques and Jean-Claude the high salaries (now as much as $70,000 a year) that they demand.

The constitutional amendment to repeal the ban on liquor by the drink passed by a narrow 51 per cent in 1970. Restaurant owners lobbied hard for it; they predicted a 10 to 15 per cent increase in business. The actual increase is impossible to calculate, because many of the restaurants of that era, like the Barn, were not capable of the transition and are now extinct. But here are a couple of measures: in Dallas the restaurant listings in the Yellow Pages have doubled since 1970, from 16 pages to 32. And the statewide tax revenue from liquor by the drink has gone up every year, from $15 million in 1972 to $133 million last year.

Proponents of liquor by the drink predicted that it would change Texas, but hardly anyone understood how great the change would be. New York’s master Chinese chef, Wen Dah Tai, moved to Houston in 1979 to open Uncle Tai’s Hunan Yuan; he would not be here but for liquor by the drink. The Republican National Convention will be held in Dallas next year; that would never have come about during the brown bag era. Back in 1968 a young Houston lawyer named Marion Sanford suggested to his wife that they check out all the good restaurants in town, one each week; “It didn’t take long,’’ he recalls, “before we were looking for something else to do on weekends.”

Just as liquor by the drink transformed restaurants, the opening of the Galleria transformed both shopping and real estate. It established a climate in which stores of national class like Marshall Field, Tiffany, Saks, and Bloomingdale’s could thrive, even though some of those stores did not locate in the Galleria itself. It rendered obsolete the shopping trip to New York and weakened Texas’ self-perception that it was an isolated outpost.

The changes that Southwest Airlines effected are not as obvious as those caused by liquor by the drink and the Galleria, but they are no less pervasive. Some are visible only to those people whose lives they have touched: the San Antonio cancer outpatient who can live at home and make weekly trips to M. D. Anderson for treatment; the Houston oilman who expanded his company as Southwest expanded its route structure; the professor who can hold joint appointments at UT-Austin and UT–El Paso. The changes show up in odd statistics, such as Texas’ number one ranking in ski wear sales and ski trips, which resulted from Southwest’s service into Albuquerque. Southwest facilitated the statewide spread of bank holding companies and the rise to preeminence of Houston law firms in Austin lobbying. The South Padre Island condominium boom began only after Southwest began flights to the Rio Grande Valley in 1975. In the first year of Southwest’s service, air traffic into Harlingen tripled.

Southwest ended the isolation of Texas’ hinterlands. On a Friday night the Harlingen airport, a teeming mass of humanity, resembles the Mexico City bus depot. Before Southwest served El Paso, most departures from that city were westbound; now most are to the east. The Dallas-Lubbock route is among the two hundred most heavily traveled city pairings in the nation. Texas’ two urban poles were also brought closer together: Houston-Dallas air traffic rose from thirty-second on the same list to fifth within a decade, bringing some similarities to two dissimilar cities. Dallas now has a Galleria, Houston will have a NorthPark, Uncle Tai has opened a branch in Dallas. Nor is it coincidence that Southwest flies more children proportionately than any other airline—Houston and Dallas have the two highest divorce rates among big cities nationally.

With liquor by the drink, the Galleria, and Southwest Airlines all coming into being about the same time, the effect was cumulative. Liquor by the drink enabled Galleria developer Gerald Hines to attract a major hotel to his project; when it opened, the Houston Oaks was the best in town. In turn, the success of the Galleria caused a neighborhood to spring up around it that included restaurants like Tony’s and Uncle Tai’s. The Galleria area had 100,000 square feet of office space in 1967; now it is pushing 20 million, with buildings by I. M. Pei, Cesar Pelli, and Philip Johnson. Southwest helped bring the people: last December the morning flights into Houston were packed with befurred women on one-day Christmas-shopping sprees.

The sale of the Dallas Times Herald is the least dramatic of the ten landmark changes of the boom era, but in many ways it is the most significant of all. The change it helped bring about—a deepened public awareness and a capacity for self-criticism that simply didn’t exist in Texas before 1970—is evidence that the other changes in the state are neither superficial nor transitory.

The braggadocious Texan was no false stereotype. In The Super-Americans Bainbridge offers several examples that suggest a stunning lack of perspective: the director of Fort Worth’s Casa Mañana theater asserting that it was “without a doubt the finest theatre of its kind in the United States”; a Houston critic pronouncing the fledgling local opera company “the most astonishing prodigy on the nation’s musical scene”; a Dallas Morning News writer proclaiming that the success of the local opera company proved that “Dallas has, above all, the Neiman-Marcus complex or what has been called the Dallas News complex. This is that Dallas’ best must be the most unique in the world.” Bainbridge’s publication of these excesses apparently did not have a deterrent effect. In the sixties prominent Houstonians were still touting the Burke Baker Planetarium as “the most sophisticated science teaching device on earth” and claiming that “Dixieland is rooted as deeply in Houston as in New Orleans.”

The Herald’s new owners did not make a point of informing Texans that their cultural emperors were without clothes, but they didn’t have to. It was enough to ignore the old rule, laid down by the chief amusements critic for the rival News but followed by art—and political and social—critics across the state: “Local criticism should not produce an uncongenial atmosphere for the best art life a community can afford.” The events of the boom years erased the historic self-doubts about the state’s relative standing to the East and gave us the confidence for the first time to be critical of ourselves.

The elegy for the old oligarchy was sung by Johnny Nelms, a freshman legislator from Pasadena. As the clock ran out on the final minutes of the tumultuous 1971 legislative session, members of the Dirty Thirty opposition to Speaker Gus Mutscher shouted for recognition. They wanted the floor to denounce their enemy one last time. Finally Mutscher called on Nelms, one of his trusted back-bench supporters, who stepped to the microphone at the front of the House chamber carrying a guitar. The song that he sang as the old order expired was called “Everything I Touch Turns to Dirt.”

That was the session of the Sharpstown scandal, when Texans got a rare look at the raunchy innards of state politics. According to documents filed by federal officials, Mutscher had maneuvered two banking bills through a previous Legislature for Houston developer Frank Sharp. Meanwhile, Sharp was manipulating the stock of his bank, and Mutscher was trading heavily in that stock. By the time the investigation was over, Mutscher had been convicted of accepting a bribe. Governor Preston Smith had been implicated in the suspect stock trading, Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes had lost his bid for governor, and the course of Texas politics had changed forever.

Sharpstown was the most dramatic of a series of changes whose cumulative effect was to end the hegemony of the state’s ruling establishment. The scandal was a turning point not because of the much-ballyhooed reforms passed in its wake by the 1973 Legislature—disclosure, ethics, campaign finance, and lobby-control laws that actually had little subsequent effect—but because it tore Texas politics loose from its moorings. It wiped out the old state leadership—Smith, Mutscher, and Barnes—at a time when politics, like everything else in the early seventies, was already undergoing wrenching changes. The first true reapportionment of the Legislature, which took effect with the 1972 elections, broke the rural hold on what had become an urban state. Single-member districts eliminated the power of downtown cliques to handpick and control entire slates of candidates. The population explosion brought to the big cities Republicans from the Northeast and the Midwest who neither knew nor cared about the state’s conservative Democratic tradition. At the same time, old issues like states’ rights and industrial development, which had dominated political discussion for decades, suddenly lost their steam; as a consequence, the conservative-liberal feud that had defined Texas politics since 1940 lost its passion.

Sharpstown ensured that the transition to a new political era would not be smooth. In the Legislature the 50 per cent turnover it caused, along with redistricting, doomed the old ways—a development that was mostly good riddance. The leadership surrendered power to the membership; the days when the Speaker and the lieutenant governor determined the fate of every bill were over. The bovine submissiveness of the average legislator—back in 1969 one rural legislator turned down a plea for support from a dissident colleague with the comment “I’m just a political whore, son”—was replaced by a growing sense of professionalism. The good ol’ boy lobbyists who had devised legislative strategy during poker games with the leadership in the sixties yielded to aggressive young pros from the giant Houston law firms.

The most obvious effect of Sharpstown was in the governor’s office. Barnes, the heir apparent, was the political embodiment of the oligarchy, a confidant of power brokers like Bob Strauss in Dallas and Walter Mischer in Houston. Never implicated in the scandal, he was nonetheless tarnished by his incumbency and swept out of office along with everyone else. In his stead came Dolph Briscoe, a crucial figure in the decline of the old oligarchy (of which, as one of the state’s largest individual landholders, he himself was a member) who had neither the inclination nor the skill to react to the upheavals of the day. He had a thoroughly rural mind, only a decade out of place—but it might as well have been a century. By the time he was beaten in the 1978 primary, he had neither prevented the flow of power from country to city nor kept the urban establishment loyal to the Democratic party. Thus there is a straight line from Sharpstown to the election of Bill Clements, the first Republican governor since Reconstruction.

The big losers were the barons of the county-seat fiefdoms like San Augustine and Victoria. It is hard to conceive that as recently as the sixties, one might as well have forgone statewide ambitions without the blessings of the San Augustine gang, whose point man in Austin was old LBJ hand Ed Clark, or that Victoria was considered on a par with Houston and Dallas as a source for political funds. But nowhere did the old order dissolve so swiftly and completely as in Dallas, where the collapse of the Citizens Charter Association (CCA) symbolized the changes—white flight, the dispersal of business leadership away from the central city, the broadening of the political base to include minorities—that were taking place in urban Texas.

San Antonio had its Good Government League and Houston had its city hall network, but few cities anywhere have had an organized, efficient establishment to match Dallas before 1973. The CCA was its political arm, and for three decades the organization was invincible. Its committees interviewed prospective candidates—in Dallas you didn’t run for office; you were picked—and their membership rosters read like a who’s who. The slates that they devised typically consisted of small businessmen, and they rolled up margins of two to one, which was not surprising, considering the immense sums spent on their behalf—$300,000 in 1965 for nine council jobs that paid $20 a week.

The civic arm of the establishment, and its soul, was the Dallas Citizens Council, formed by R. L. Thornton in 1936 to lure the state centennial celebration to Dallas. Thornton, then the head of the Mercantile Bank, was frustrated by bureaucratic problems in trying to get other organizations to commit money and time to the centennial. Finally he presented the head of First National with a proposition: organize what he called the Yes and No men—all bosses, no subordinates, no lawyers or other professional men—and, as he put it, “you come or you ain’t there and you take what happens.” Membership was by invitation only—for life.

It was a true oligarchy. The Citizens Council decided what Dallas needed to do and the CCA elected the people to do it, whether it was the building of the Central Expressway (the state’s first freeway) or the defeat of ultra-right Republican congressman Bruce Alger, who became an embarrassment to the city after the Kennedy assassination. So in harmony were city government and the oligarchy that the city manager’s position became an apprenticeship for Republic National Bank, with one—James Aston—going on to become Republic’s president.

But the events preceding 1973 damaged the CCA beyond repair. The Herald‘s purchase was pivotal; the old publishers had been members of the Citizens Council (the News’ Joe Dealey was the organization’s secretary), and while their papers faithfully reported opposition charges that, for example, bond money wasn’t spent on poor areas, such claims were seldom investigated. The new Herald observed no such ground rules, with the result that a 1971 survey showed that a majority of the citizens of Dallas no longer identified the CCA with good government. The CCA lost the mayor’s race that year to Wes Wise, mainly because it couldn’t find a strong opponent. In 1973 the CCA begged Aston to leave Republic and challenge Wise for mayor, but the bank holding company era had begun and he said no. The CCA’s council slate consisted of three lawyers, two blacks, one Mexican American, one woman, and only three white businessmen. Just a few years earlier, liberals had attacked the CCA; now it was the Republicans’ turn to join in. The advent of single-member council districts in 1975 brought the denouement. The Citizens Council still survives, but without the CCA its struggles have been fruitless, symbolized by the inability of the city to decide on how to enlarge the Central Expressway, the thoroughfare that was once a monument to an oligarchy and now is its epitaph.

Change is cause for celebration, but it is also cause for lament. To see what we have gained is also to see what we have left behind. Texas before the boom of the seventies was often raw and graceless, but it was a place that could not be confused with any other. This was not always for the better. Only in Texas would an orchestra (in San Antonio) punctuate the rousing climax of Bolero by having the timpanist fire blanks from a pistol. Only in Texas would a college (Howard Payne, in Brownwood) stage A Midsummer Night’s Dream as a western with Puck dressed in a coonskin cap. Only in Texas would a leading newspaper (the Dallas News) regularly refer to the U.S. Supreme Court in its editorials as “the courtnik.”

For the most part, however, distinctiveness has always been a Texas strength. It enabled us to retain our roots as we evolved from an agrarian culture into an urban one. Our institutions, from barbecue to banks to brown bags, were common ground. Now many of them are gone. Does the popularity of Southwest Airlines portend that people will no longer get the sense of Texas in its vast entirety that comes from being on the road? Will big oil companies like Shell replace the wildcatter as the essence of the state’s oil industry, just as the big Houston law firms have replaced the good ol’ boys in lobbying? Will the next generation of urban Texans feel the same ties to the land, to the rural past, as this one does?

I know many people who believe that the answers are already clear: no. They mourn the changes of the boom years and believe that Texas has paid for progress with its soul. I disagree. The brown bag and the rogue politician are flamboyant reminders of another time, but it is one that Texas is better off for having left behind. We are a more sophisticated, more economically secure, more politically diverse, and more self-confident state today than ever before. Texas has molted a colorful but nonessential skin.

What is essential, I believe, is a sense that Texas is truly a place unto itself. Its borders contain a compression of frontier America: the inexorable progression from east to west of ocean to desert, from north to south of American heartland to a foreign country. This geography has made Texas the spiritual heir to the frontier and its values—above all, a sense of expansionism and optimism about the future that has been reinforced since 1973 but is being tested now that the boom is leveling off. If the day comes when we truly believe that the best times are behind us, then sure enough, Texas really will be just like everywhere else.

Then and Now

Schmoozing

Politicos don’t hang out like they used to.

Texas politicians once whiled away the evenings drinking beer under the oaks behind Scholz’s (left), which in its soul has always been an old-fashioned Central Texas Biergarten. Today the political hangout of choice is the Quorum, where the drinks are mixed, thank you, and the setting is plusher and thoroughly urban.

Getting around

The great airline war revisited.

It used to be that the Texas airline was Braniff, a high-style carrier that spanned the globe from its base in Dallas. Now Braniff lives on only in the courts, and Southwest, the no-frills inventor of the ten-minute turnaround, is king. The change symbolizes Texans’ increasing self-confidence: we’re happy to stay at home.

Soaking Up the Sun

Building on the sands of time.

Once upon a time, South Padre Island was a deserted, even idyllic Texas beach, perhaps because it was so hard to get to. Now, thanks to the blossoming of the Harlingen airport and a decade of boom times, the beach is lined with bodies—and condos. Nobody’s in danger of getting that lonely feeling on South Padre anymore.

A Fancy Meal

Proof that there is life after the T-bone.

1973: A lot of bites for your buck. The word “gourmet” had not yet become the Madison Avenue adjective of choice for everything from pheasant to potato chips, and when Texans went out to eat at a nice restaurant, they still wanted meat and potatoes. What filled the bill was a rare T-bone with béarnaise sauce (shades of the future), a stuffed baked potato topped with melted cheese, tossed green salad with Roquefort dressing, cheesecake with cherries, and a big glass of Gallo Hearty Burgundy.

1983: Less is less. Nouvelle cuisine, that darling of authentic and ersatz French chefs from Amarillo to Waco, is still going great in the Lone Star State, having brought us ze duck in mango sauce, ze snow peas, ze multi-lettuce salad with warm goat cheese, ze three-vegetable terrine, ze kiwi fruit tart, ze half-full glass of 1976 Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and ze hunger pangs at midnight. Can’t a guy get a plain old steak anymore? Sure, but be prepared to completely lose face with Pierre, your waiter.

The Hubs

Love conquers all.

In 1974 the Dallas–Fort Worth Regional Airport (top) opened to fanfare that would have been appropriate for Sam Houston’s arrival at the pearly gates. Texas was going to find greatness as the place where America changed planes, and poor old Love Field was mothballed. Today DFW is booming—but so is Love, and with a deeper effect on the daily lives of Texans, who spend a lot more time on the Houston-Dallas axis than they do hitting N. Y. and L.A.

The Skylines

Seventy-five stories and counting.

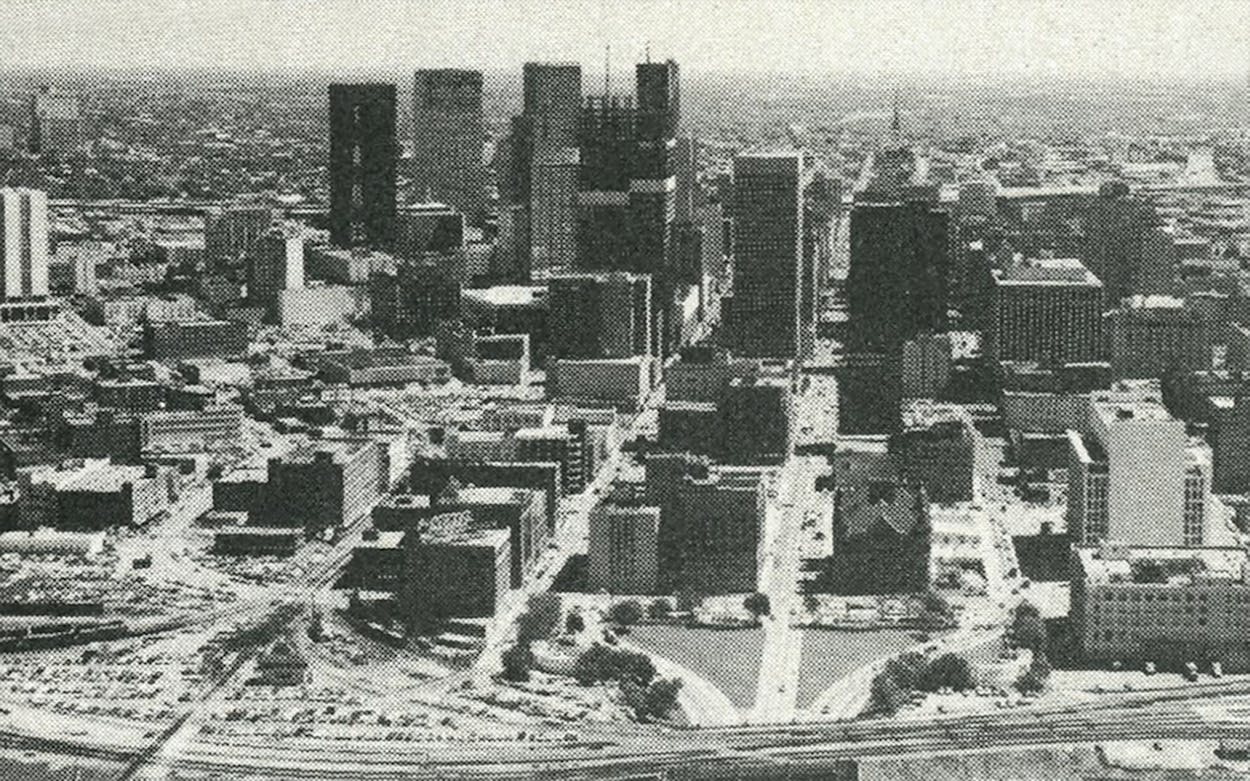

Dallas: In 1973 One Main Place was the new kid in town, and the First International Building was under construction. Now there’s Reunion Tower, and the gaps have been filled in, but the change is not nearly as dramatic as Houston’s. The seventies were the oil decade in Texas, and Houston was where the big oil money was.

Houston: In 1973 One Shell Plaza, at 50 stories the tallest building west of the Mississippi, towered above everything else. Today it’s easy to miss, tucked away between the Allied Bank Plaza (71 stories) and the Texas Commerce Tower (75 stories), and Louisiana Street is a New York–style steel-and-glass canyon.

Unreal Estate

A slightly out-of-date investment tip.

Are you sitting down? This house, in Houston’s pleasant but hardly sumptuous West University Place, sold in 1973 for $26,500. It sold again last year for $250,000, making it one of the few investments of the seventies that outpaced even crude oil.

Football Factories

How the Cowboys became Irving’s team.

In the old days, the eyes of Texas—and the bodies of Dallas folks—were drawn to the Cotton Bowl, on the grounds of Fair Park at the crumbling edge of downtown. Football was still an inner-city game.

After ten years of white flight, the center of the football universe has moved to sleek Texas Stadium, an island in a sea of suburban highways.

The Numbers

Some statistics that don’t lie.

Signs of Life

| 1971 | 1981 | |

| Births per 1000 population | 20.0 | 19.1 |

| Deaths per 1000 population | 8.3 | 7.5 |

| Marriages per 1000 population | 12.2 | 13.2 |

| Number of marriages | 140,390 | 194,762 |

| Divorces per 1000 population | 4.8 | 6.9 |

| Number of divorces | 55,568 | 101,856 |

Just Folks

| 1970 | 1980 | |

| Total population | 11.2 million | 14.2 million |

| Anglo | 9.7 million | 11.2 million |

| Black | 1.4 million | 1.7 million |

| Hispanic | 1.8 million | 3.0 million |

| Urban | 8.9 million | 11.3 million |

| Rural | 2.3 million | 2.9 million |

Drinking Up and Eating Out

| 1971 | 1981 | |

| Alcoholic beverage revenue (actual dollars) | $72.3 million | $248.1 million |

| Alcoholic beverage revenue (constant dollars) | 59.6 million | 91.1 million |

| Number of mixed-beverage permits | 1,534 | 8,885 |

| 1974 | 1981 | |

| Restaurant revenue | ||

| Statewide | $2.3 billion | $6.9 billion |

| Harris County | 449.0 million | 1.6 billion |

| Dallas County | 350.2 million | 1.0 billion |

| Number of restaurants | ||

| Statewide | 26,772 | 34,639 |

| Harris County | 3,938 | 6,015 |

| Dallas County | 2,371 | 3,258 |

Passing the Bucks

| 1971 | 1981 | |

| Per capita income (actual dollars) | $3,692 | $10,729 |

| Per capita income (constant dollars) | 3,044 | 3,940 |

State Capital

| 1971 | 1981 | |

| Bank deposits | $30 billion | $105.3 billion |

Black Gold

| 1971 | 1980 | |

| Crude oil price per barrel | $3.48 | $21.59 |

| Number of barrels of crude oil produced | 1.2 billion | 977.4 million |

Down on the Farm

| 1971 | 1981 | |

| Number of farms | 210,000 | 186,000 |

| Farm revenue (actual dollars) | $3.9 billion | $10.1 billion |

| Farm revenue (constant dollars) | 3.2 billion | 3.7 billion |

Changing Colors

| 1971–72 | 1981–82 | |

| HISD students (percentage of total) | ||

| Black | 37.6 | 44.3 |

| Hispanic | 15.5 | 29.7 |

| Anglo | 46.4 | 23.3 |

| DISD students (percentage of total) | ||

| Black | 36.1 | 49.4 |

| Hispanic | 9.5 | 20.8 |

| Anglo | 53.9 | 27.7 |

The Players

Who found a place in the sun and who got eclipsed.

Mayor of Houston

Louie Welch

Then: the ultimate glad-hander.

Kathy Whitmire

Now: the ultimate manager.

Restaurateur

Harry Akin, Night Hawk

Then: chopped steak and ketchup.

Tony Vallone, Tony’s

Now: veal and demiglace.

Dallas Publisher

Joe Dealey, Dallas News

Then: the Dallas oligarchy.

Otis Chandler, Times Herald

Now: the Los Angeles oligarchy.

University Leader

Frank Erwin, UT regent

Then: politician as educator.

Peter Flawn, UT president

Now: educator as educator.

Politician of Liquor

Abner McCall, Baylor

Then: most potent Baptist.

Nick Kralj, the Quorum

Now: most potent saloonkeeper.

Developer

Frank Sharp, Sharpstown

Then: the master manipulator.

Gerald Hines, the Galleria

Now: the master builder.

Banking Power

Wright Patman, Congress

Then: populist who hated big banks.

Ben Love, Texas Commerce

Now: big is beautiful.

Hispanic Boss

A. Y. Allee, Captain

Then: tough Texas Ranger.

Henry Cisneros, politician

Now: the mayor of San Antonio.

Most Important Legislator

Gus Mutscher, Brenham

Then: corrupt, rural, white.

Craig Washington, Houston

Now: clean, urban, black.

Airline Kingpin

Harding Lawrence, Braniff

Then: Calder planes, Pucci uniforms.

Herb Kelleher, Southwest

Now: just plain folks.

Wetting Your Whistle

Good-bye, brown bag.

Before 1971, anyone out for a night on the town had to take his bottle with him, shrouded, as convention decreed, in a brown paper bag. The status quo was maintained by people who, as the saying went, drank wet and voted dry, but in the first year after liquor by the drink was legal, 19 of the 25 counties with the highest alcoholism rates were dry. Now the martini may or may not be the state drink; if you’re looking for a brown bag, try the grocery store.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads