After months of pressure from Texas politicians and border agents, President Joe Biden recently announced that he would dispatch 1,500 active-duty troops to help patrol the U.S.-Mexico border. The number of asylum seekers set to cross the border has begun to increase dramatically, especially near Brownsville and El Paso, as many migrants anticipate the expiration of Title 42, the once obscure, now infamous public health statute that both Donald Trump and Biden have used to essentially block migrants from applying for asylum.

Immigration agents welcomed the federal support. For months Border Patrol chiefs, including Gloria Chavez of the Rio Grande Valley Sector, which spans from the western reaches of the Valley to the Gulf, have called for more hiring. “I do not have enough agents,” Chief John Modlin, of the agency’s Tucson Sector, told Congress in February. Texas politicians, meanwhile, were less enthusiastic about Biden’s move. Despite calling for more federal help on the border for years, Governor Greg Abbott took to Twitter to slam the president. “Biden says he will deploy 1,500 troops to the border — primarily to do paperwork. And only for 90 days. This does nothing to stop illegal immigration,” Abbott wrote, before touting his Operation Lone Star effort, under which he deployed state troopers and national guard to the border. “I deployed up to 10,000 Texas National Guard to the border to fill the gaps created by Biden’s reckless open border policies.”

Texas Monthly wanted to find out how big these “gaps” really are along the Texas border. So we set out to answer a question: If every federal, state, and local law enforcement officer assigned to the Texas-Mexico border lined up along that border, Hands Across America–style, how close to one another would they be?

There’s a vast force deployed on the Texas-Mexico border, which includes armed agents from every level of government. The largest federal presence is from Customs and Border Protection, the agency that oversees Border Patrol. CBP is by far the largest federal police force—with more than 60,000 employees, it’s almost twice as large as the FBI—and about 20,000 Border Patrol agents work along the nation’s southern border. In Texas, specifically, this force was made up of around 9,153 agents across Texas’s five border sectors in 2020 (a small number of those worked in the New Mexico portion of the El Paso Sector; a state-by-state breakdown was unavailable).

But Abbott has never been satisfied to just leave immigration enforcement to the feds, so our calculation doesn’t stop there. Under Operation Lone Star, the border-enforcement initiative he launched in 2021, Abbott has deployed more than 10,000 additional agents—mostly Department of Public Safety cops and National Guard troops. OLS has effectively doubled the immigration force on Texas’s border with Mexico.

And there’s even more. The federal government has actively encouraged—and funded—hundreds of local police departments to support federal immigration enforcement. Under Operation Stonegarden, a $90 million program, local police departments can hire officers, or pay existing ones overtime, exclusively to patrol the border. These cops don’t have any authority to enforce immigration law, but, like OLS personnel, they can enforce trespassing laws on private property and other incidental crimes that those crossing the border might wittingly or unwittingly commit.

In Texas, at least 137 local police forces—and not just ones directly on the border—have received Stonegarden funding. Along the border itself, these forces include, from west to east, the county sheriffs’ offices in El Paso, Presidio, Kinney, Maverick, Webb, Hidalgo, Starr, and Cameron Counties. They also include municipal police departments in Combes, Eagle Pass, El Paso, Harlingen, Laredo, Rio Grande City, Roma, and potentially many others. The Kickapoo Traditional Tribe, which has a reservation on the border just south of Eagle Pass, has also received Stonegarden funding.

We don’t have the data on how many officers in each department have been devoted to border enforcement, but the number is substantial. Even in tiny Kinney County, with a population of just more than 3,100, the sheriff told local news that Operation Stonegarden funds have let him hire multiple part-time deputies to patrol the border.

So how much of the border can officers from all those various agencies cover? Texas’s border winds some 1,254 miles along the Rio Grande, from the mountainous deserts of Ciudad Juárez–El Paso to the sandy beaches of South Padre–Matamoros.

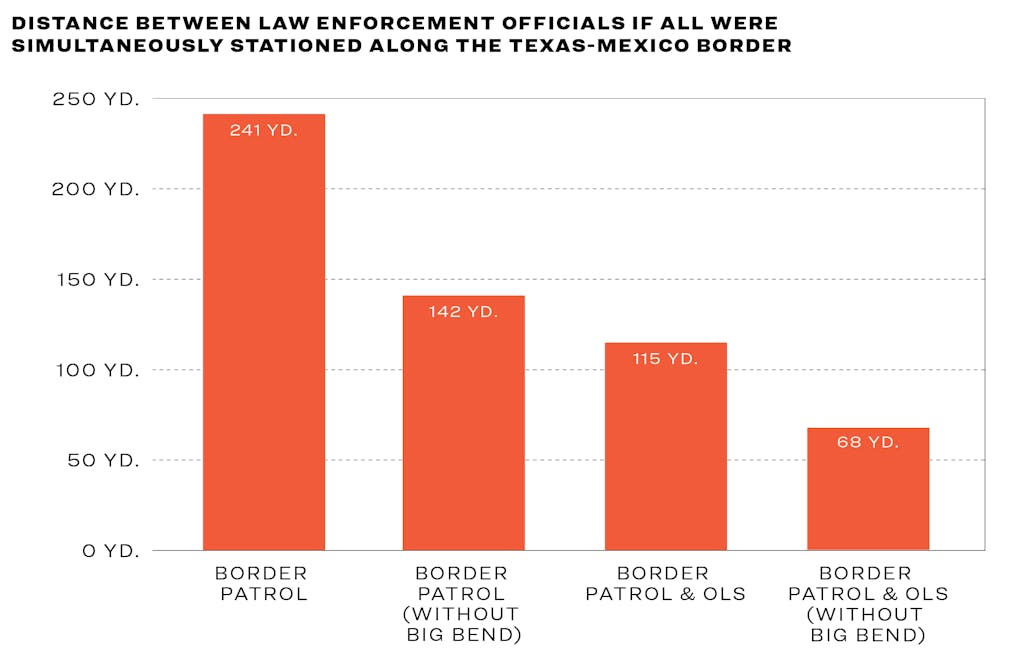

If all the CBP agents—but no one else—lined up along the border at the same time, they’d all be about 241 yards apart. That’s about the length of two football fields, including the end zones. Barring hillsides and thick mesquite obscuring agents’ views, they would all be within view of another officer. (Of course, this is only a thought exercise: agents aren’t all on duty at the same time, and even if they were, not all are assigned to patrol.)

But there’s an outlier here: the vast Chihuahuan Desert of West Texas. In manning the Texas-Mexico frontier, Border Patrol has segmented the border into a series of sectors. From west to east, these are: the El Paso Sector (which covers all of the New Mexico border as well), the Big Bend Sector, the Del Rio Sector, the Laredo Sector, and the Rio Grande Valley Sector. Among these, the Big Bend Sector is by far the longest, at 517 miles—more than the lengths of the Del Rio Sector (245 miles) and the Laredo Sector (136 miles) combined. However, it’s also the least-manned sector, with only 540 agents as of 2020. By contrast, the second-least-patrolled Texas sector, Del Rio, had nearly three times as many agents in 2020, while the RGV sector had 3,119 agents. The reason for this disparity is simple. The Chihuahuan Desert does most of the enforcement work for immigration agents: Big Bend country is so hostile, so dry, so sparsely populated, and so devoid of cross-border freeways, very few migrants or smugglers cross there.

So, if we remove the Big Bend Sector from the equation, the numbers look much different. Throughout every other region of the border, agents would be just 142 yards apart. That’s around the length of a normal city block. That’s close enough to see someone throw up the “Hook ’em, Horns” sign.

When you throw in all the OLS personnel, here’s how the numbers look: across the whole length of the border, agents could line up 115 yards apart. That’s about the length of one football field, including the end zones. And if you factor out Big Bend again, they’re even closer together: just under 70 yards apart. That’s the length of a hockey rink (and of the longest recorded pass attempt in NFL history, a desperate and unsuccessful 70.5-yard Hail Mary slung by Austin-born Baker Mayfield for the Cleveland Browns in 2020.)

The agents are getting close to one another, but what if we factor in those local police using Stonegarden funding? The average local police force in Texas has about 70 officers (not counting other desk staff), according to 2019 data from the FBI. That means for the sixteen border police forces with Stonegarden funding mentioned above, we can expect around 1,120 cops. If every single one of them—not just those assigned to border duties—joined up with the Border Patrol and OLS agents on the border, all officers would be 109 yards apart. Take out Big Bend again, and the agents are standing just 64 yards apart.

Obviously this is all just a way to think about the numbers, not an actual example of what patrols could look like. Because human beings cannot work 24 hours a day, these agents are not all on patrol at the same time. But, given the sheer manpower already at the border, it’s a question of significant debate how much difference additional personnel really make. As Border Patrol exploded from just 4,000 agents in the early nineties to roughly 20,000 today, some argued the agency had been the victim of bureaucratic bloat. An analysis by the libertarian Cato Institute in 2017 found that Border Patrol agents had apprehended, on average, just 1.1 border crossers per month from January through September of 2017—down from 42 a month in 1986. At the time, Alex Nowrasteh, the Cato researcher behind the analysis, argued that there was “no good reason” to hire more Border Patrol agents. Six years later, with border crossings at record highs, Nowrasteh told me he no longer stands by that specific argument, but he still believes that hiring more patrol agents is not the most efficient use of taxpayer dollars. “Times have changed, but expanding legal immigration through further grants of humanitarian parole would make hiring additional Border Patrol agents unnecessary,” he said.

We may have also reached an asymptote of a different sort. When he was president, Donald Trump made a massive CBP hiring push, hoping to add more than 5,000 new Border Patrol personnel. Even during years when migration was at record lows, expanding the force proved difficult. When CBP began its hiring push in 2018, it only managed to hire 188 new agents. It hired 3,448 new employees the next year, but accounting for retirements, the Border Patrol force only expanded by 93 agents. Biden has funded CBP to hire more agents, but it’s not clear if the agency can hire as quickly as employees retire. The country may have reached its limit of civilians willing to volunteer to patrol the border, in other words. That might be the simplest reason why both Governor Abbott and President Biden have begun sending military troops instead.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Border Patrol

- Joe Biden

- Greg Abbott