Sol Wachtler, the former chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals, famously quipped that a good district attorney could indict a ham sandwich. But given the well-documented legal woes of the Texas attorney general, it’s fair to ask whether a good ham sandwich could indict Ken Paxton. Since he was elected the state’s top law enforcement officer in 2014, Paxton has been criminally charged with felony securities fraud, sued for civil fraud by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and accused of abusing his office in a whistleblower complaint filed by seven of his top aides, who say he did so to benefit a campaign donor. He is currently under investigation by the FBI and the State Bar of Texas.

Paxton is also the odds-on favorite to win a third term this fall. In March, he received almost twice as many votes as the second-place GOP primary finisher and his runoff opponent, land commissioner George P. Bush. Holding the endorsement of former president Donald Trump and facing the scion of a dynasty whose popularity has receded, Paxton is widely favored to win the runoff.

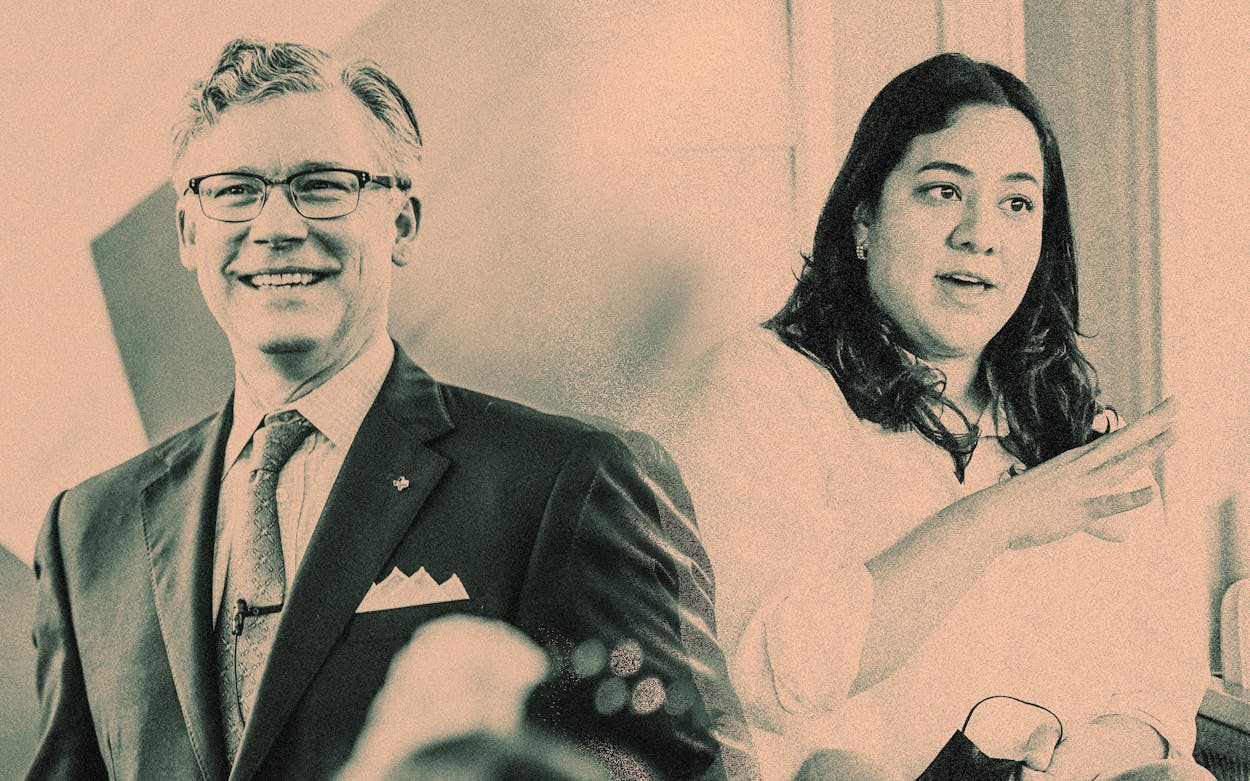

If he does prevail, he’ll face the winner of the Democratic runoff, which pits civil rights attorney Rochelle Garza against former Galveston mayor Joe Jaworski. At first glance, the two candidates are a study in contrasts. Garza is a 37-year-old Brownsville native and daughter of two public school teachers who successfully sued the Trump administration on behalf of a seventeen-year-old detainee who was seeking an abortion. Her run for attorney general is her first political race. Jaworski, 60, is a third-generation trial lawyer and the grandson of Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski. He is a seasoned politician, having served three terms on the Galveston City Council and one term as mayor. In March, 43 percent of Democratic primary voters chose Garza in a five-candidate field, with 20 percent favoring Jaworski.

Despite Paxton’s dubious distinction as the most vulnerable Republican statewide candidate, a poll of both parties’ attorney general candidates conducted by UT-Austin’s Texas Politics Project in February found that 52 percent of Democratic voters “had not thought enough about the race to have an opinion.” Jim Henson, who leads the Texas Politics Project, said that “Democrats are just not paying attention to these down-ballot races. All the oxygen, to the extent there was some, was at the gubernatorial level.”

Cal Jillson, a political science professor at Southern Methodist University, pointed out that four of the five statewide Democratic primary races went to runoffs—an indication, he said, of voters’ lack of familiarity with the candidates. “Besides Beto, and maybe [lieutenant governor candidate] Mike Collier, because he’s run two or three times before, there were a lot of almost invisible candidates,” Jillson said. “There’s a lot of confusion, and I think that’s the case in the attorney general race.”

The Texas Democratic party insists that beating Paxton is an urgent priority. “We feel like defeating him would be like chopping off a head on a three-headed monster,” said party spokesperson Angelica Luna Kaufman (the other two heads being Governor Greg Abbott and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick). But Democrats don’t appear to have much of a sense of urgency. Gilberto Hinojosa, the party’s chairman, told me that he isn’t yet concerned by low voter engagement and that most Democrats are simply too busy to pay attention to the primary. “They’re more concerned about making sure they have food on the table for their kids, getting them off to school on time, working to make enough money to pay their mortgage.”

Hinojosa believes—or, given his party’s 27 years of failure in statewide races, has blind faith—that voters will rally around the eventual Democratic nominee to kick out the much-loathed Paxton. “Once they check into what this attorney general is all about and what he’s done, it won’t be a hard choice to make.”

Garza and Jaworski share the same belief that Paxton can be defeated. “We have the most corrupt attorney general in the United States,” Garza told me. “He is under indictment. He just went through a rough primary, and he’s going into a runoff. He’s under FBI investigation.” Jaworski seems equally optimistic: “With the punitive way government is approaching the citizenry, there’s a real opportunity [for Democrats]—especially so in the attorney general’s race, because Mr. Paxton has alienated people on the Republican side as well.”

With nearly identical platforms, the candidates have emphasized their personal histories. Jaworski likes to talk about how his decision to use federal disaster relief money to build public housing in Galveston cost him reelection as mayor. “I lost because I took a principled stand, defending the rights of people to live in affordable housing,” he told me. Garza tells the story of her battle to secure an abortion for “Jane Doe,” a pregnant minor in custody whose choice was nearly blocked by the Trump administration. Garza fought the case all the way to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, where she eventually won—over a dissent from then–circuit court judge Brett Kavanaugh. When Trump nominated Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, Garza testified against him before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

“That case was an example of fighting for someone who had been overlooked by our legal system,” Garza said. “Someone who the Trump administration and Brett Kavanaugh did not believe mattered. It’s an example of what you can do with smart advocacy and legal maneuvering.”

Compared with the high-priced GOP primary for attorney general—Paxton has amassed a $4.7 million war chest—both Democratic candidates are running relatively lean campaigns. Jaworski has received about $1 million in donations and has about $10,000 cash on hand. In addition to spending $63,000 of his own money, Jaworski has received major donations from Houston hedge fund manager Jerome Simon, Philadelphia entrepreneur Jeffrey Westphal, and Houston attorney Joseph D. Jamail III. Garza has collected $240,000 in donations with $70,000 on hand. She rolled over $35,000 from her short-lived congressional campaign and received a $12,000 donation from Annie’s List, an Austin-based political action committee devoted to electing progressive Texas women.

Four years ago, Paxton won reelection for a second term by just 3.6 points over law professor Justin Nelson, another of the all-but-unknown politicians the state Democratic party has frequently nominated for statewide offices. But 2018 was a blue wave election. Should Paxton win his party’s nomination, it will likely take a federal indictment—the FBI is investigating the bribery and abuse of office alleged by Paxton’s former aides—to give Jaworski or Garza even a chance. “It would take something major happening with his ethical and criminal problems between now and November to change those odds,” Henson told me.

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde: to be indicted once may be regarded as a misfortune, but to be indicted twice looks like carelessness.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton