Texas Democrats are mad as hell and they aren’t going to take it any more. Or will they? That was the question looming over this weekend’s state party convention in Dallas, where thousands of deep-blue stalwarts gathered to reconnect, regroup, and react to what’s felt like an endless onslaught of body blows from state Republicans.

First there was the 2020 general election, when Democrats failed to unseat Senator John Cornyn or win back the Texas House, as they had hoped. Then came the disastrous Eighty-seventh Legislature in 2021, during which Republicans drew up new, even more heavily gerrymandered congressional and legislative districts. Republicans used the session to ram through a series of particularly noxious bills that restricted voting access, allowed Texans to carry a loaded handgun in public without a license or training, and offered a cash bounty for reporting anyone assisting in an abortion after six weeks of pregnancy. The recent Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, which will trigger a Texas law banning all abortions except to save the life of the mother—without exceptions for cases of incest or rape—solidified the sense of a state Democratic party under siege.

“We are fighting something really ugly,” said Rochelle Garza, the Democratic nominee for state attorney general, addressing the Texas Young Democrats on Friday. “The Republicans are doing everything they can to attack our communities—to make our schools less safe, to remove regulations on guns, to attack trans youth and the LGBTQ+ community, to attack women by ending access to abortion care.” The Democrats directed much of their vitriol at Governor Greg Abbott, who has presided over what several speakers described as a “neofascist” turn in Texas politics. “Greg Abbott is chaos, he is corruption, he is cruelty, he is incompetence,” declared gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke during his Friday night keynote speech.

But if there was fury at Republican leaders, there was also plenty of discontent with the state Democratic Party. Chairman Gilberto Hinojosa, a former county judge from Brownsville, has led the party for ten years and was up for reelection for another four-year term. He faced two challengers, Texas Southern University law professor Carroll Robinson and former agriculture commissioner nominee Kim Olson, who came within five points of unseating incumbent Republican Sid Miller in 2018. Both candidates acknowledged Hinojosa’s accomplishments—when he took over the party in 2012, it had empty coffers and a handful of staffers, and held just 48 out of 150 seats in the state House—but said it was time for new ideas and new energy.

In an impassioned speech to the convention’s general assembly on Saturday, Robinson, who chairs the Texas Coalition of Black Democrats, reviewed the party’s three-decade run of failure—the longest drought of any state party in the country. “The last time we elected a Democratic governor was 1990,” he lamented. “We haven’t had a majority in the Texas Legislature for more than twenty years. We have got to get back to the business of winning votes.” Olson, who lives on a ranch in Palo Pinto County, west of Fort Worth, used her speech to call out the party for neglecting nonurban Texans. “I connect with the frustration of our activists, donors, and voters alike,” she said. “I can repeat and recite the challenges that I know firsthand that our great candidates have when they run in red and rural areas.”

Olson was endorsed by party chairs from sixty mostly rural counties, including the president of the Texas Democratic County Chairs Association, and hundreds of former Democratic candidates, donors, and activists. The retired Air Force colonel’s pink-clad supporters were a raucous, highly visible presence throughout the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center in downtown Dallas. Chris Langfeld, a Democratic delegate from Blanco, wore a pink KN95 mask and a pink shirt that read “Kim’s Got Your Back.” “The leadership that we’ve had just hasn’t worked for the past several years,” she told me. “We aren’t getting the results we need to get—it feels like the same old, same old. Kim just radiates energy and excitement.”

On Friday night, Olson hosted a campaign party at the House of Blues that drew hundreds of her supporters. On the outdoor patio I met Kristie and Jared Hanhart, Fort Worth residents who first met Olson in 2018 when she was campaigning for agriculture commissioner. “She’s a battle-ax,” Kristie told me with admiration. “Gilberto’s done an okay job, but it’s time for someone new. When you’ve been doing something for so long, you run out of new ideas.” Her husband nodded in agreement. “She’s straightforward, and she’s not fake,” he said. “She’s got Ann Richards vibes.”

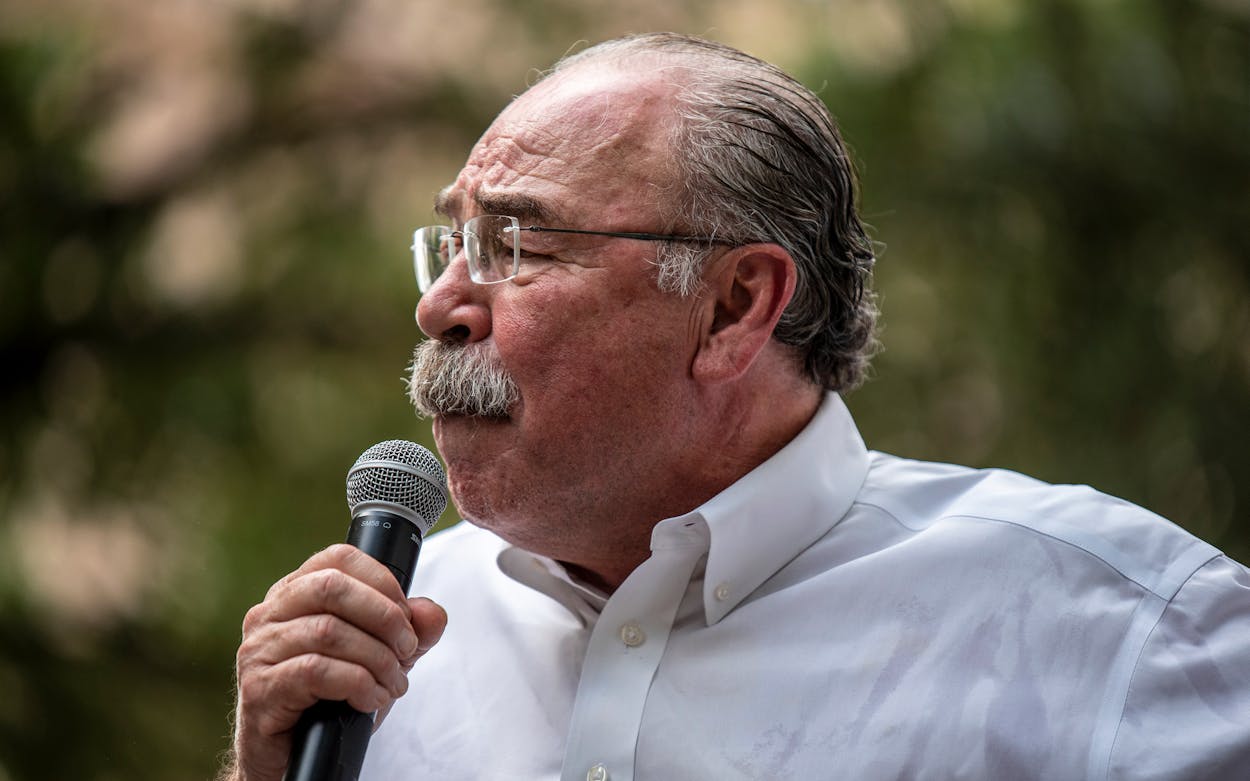

Earlier that day, Hinojosa conducted a whirlwind tour of the party caucuses, defending his decade-long tenure and making his pitch for reelection. Yes, he acknowledged, mistakes had been made. He had not given sufficient attention or resources to nonurban counties, he told the rural caucus on Friday. “I’ve been slapped around a bunch of times by my good friends, because [rural counties] haven’t gotten the attention that they deserve,” he said. “I get it, and I understand it. It’s not that I haven’t tried, but maybe I haven’t tried hard enough.” If he were to be reelected, a chastened Hinojosa promised the rural delegates, their candidates and local parties would receive “the money they deserve.”

On Saturday afternoon, as delegates started voting for party chair, I interviewed Celina Vasquez, a Hinojosa supporter from Brazos County. “We can’t change horses in the middle of the fight,” she argued. “We’re on the cusp of winning. The party has made improvements, and we’ve worked very hard to build a world-class staff, to raise money. When the party experienced losses in 2020, they put together a report, and Gilberto followed all of the recommendations. He’s also the only one who knows how to turn out the Latino vote.” (Hinojosa’s opponents disputed this claim, noting the inroads the Republican party has recently made in South Texas.)

No candidate captured a majority on the first ballot. Hinojosa received 45 percent, Olson 37 percent, and Robinson 18 percent. After the vote was announced, Robinson took the stage to announce that he was bowing out of the race and endorsing Hinojosa—something of a surprise given his vocal criticism of Hinojosa’s leadership. “I think Kim Olson is a great person, and we’ve been on the trail together, but the folks who have stood with me, come this far, want us to stand together with Gilberto Hinojosa,” he said. Robinson’s supporters evidently listened. In the second round of voting, Hinojosa won 58 percent to Olson’s 40 percent.

Olson was not amused by what she considered Robinson’s stab in the back. “It’s certainly disappointing, after listening to this person constantly talking about the need for new leadership, that he would completely change his theory,” she told me on the convention floor after Robinson’s speech. “It makes one suspect that deals were made. And it makes women around here mad as hell. Once again, you see men driving something when it was clear that people wanted a woman to lead. We are the ones getting hammered by Republican legislation. We should have a seat at the table.”

Robinson categorically denied making a backroom deal with Hinojosa. “I didn’t ask Gilberto for s—, and I don’t want s—,” he told me in a phone interview on Sunday. Robinson said he was simply following the will of his supporters, who had been put off by the attitude and behavior of Olson fans over the course of the convention. Randall Bryant, the vice chair of the Texas Young Democrats Black Caucus and a member of the nominations committee, told me that Olson’s backers on the committee disrespected Robinson’s supporters by repeatedly speaking over them and by suggesting that Olson could better appeal to white Texans.

“A Hispanic man who was supporting Olson said, ‘We need someone at the top who can speak to people with blue eyes,’” Bryant recalled. “That kind of set off a storm. I stood up and said, ‘If you’re talking about the change of demographics in the electorate, 95 percent of our new voters have brown eyes.’” (The Olson supporter could not be reached for comment.) Bryant told me that Olson’s supporters had “absolutely” alienated Robinson’s supporters—ultimately making it untenable for Robinson to endorse her.

Robinson’s supporters appear to have stuck with the devil they know rather than the devil they don’t know. After all, Robinson pointed out, Hinojosa has promised this will be his final term. “I hope some young African American will run for chair four years from now,” he told me. “We’ve never had an African American chair of this party. And African Americans are the backbone of this party.”

In the end, Hinojosa squeaked out a win despite being the second choice of more than half of the delegates. Both Olson and Robinson told me the loss was tough to swallow. But they also said the party must unite in order to defeat their common enemy this November. “As disappointed as I am, I sure as hell wouldn’t want to see another January sixth,” Olson said. “So maybe that’s what the Democratic party is about. We bring signs to our events. Republicans bring guns.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Beto O'Rourke

- Dallas