There’s a problem buried inside Texas’s latest election bill, and it’s not one of the headline-grabbing restrictions that have torn the Legislature apart during the special session. Nonetheless, it could disenfranchise a significant number of the state’s voters.

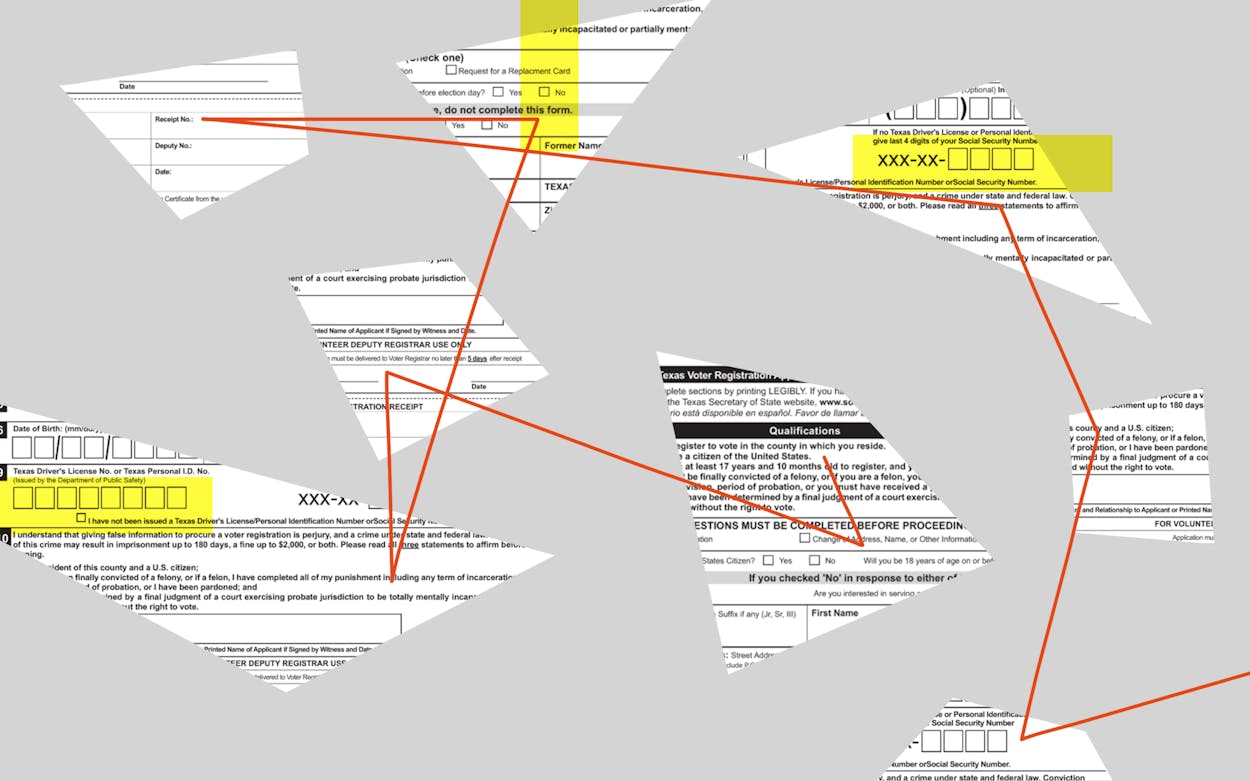

Amid all the fighting, most lawmakers have apparently overlooked a provision that would force counties to automatically reject some mail-in ballot applications. Here’s why: The Republican-authored legislation would require voters to submit either their driver’s license number or a partial Social Security number when applying to vote by mail. That number would then be cross-checked with the state’s voter-registration database. Most applicants would be fine, because almost 90 percent of all registered Texas voters have both their Social Security number and driver’s license number in the database. However, 1.9 million voters—about 11 percent of the total—have only one of the two numbers on file with the state.

During late-night testimony to a committee of the Texas House on July 10, Chris Davis, the elections administrator for Williamson County, explained that most of the voters with only one number on file wouldn’t remember which number they filed, often many years earlier, and would have to guess. “You have a 50 percent chance of the voter guessing wrong,” said Davis. Guess wrong and your application would be rejected, even if it’s been twenty years since you used your Social Security or driver’s license number to register to vote. “I challenge any person on the committee: do you remember what you filled out when you got your voter registration? I certainly don’t. And I’m in the business of this. And if [the numbers] don’t match, we’re rejecting.”

Some 11 percent of Texas voters cast their ballots by mail in 2020, so if that percentage held up in future elections, 209,000 of the 1.9 million voters with only one ID number on file with the state would be requesting mail-in ballots. If most of those voters are guessing which ID number to cite on their application, and they have a 50 percent chance of guessing correctly, then 104,500 of them would have their applications rejected. Some of these voters might find other ways to vote, including in person. But some with serious disabilities, or those who have to be out of state during the period when polls are open, would be out of luck.

Ever since the special legislative session began this month, a handful of local and state officials have tried in vain to call attention to the problem. But their pleas appear to have fallen on deaf ears. The night of the hearing, none of the fifteen House committee members—including six Democrats—asked Davis a question about the risks of ID-matching. Instead, they voted the bill out of committee with no changes. Two days later, the full Senate adopted a nearly identical companion bill, also with no discussion and no changes to the provision.

During the regular session, which stretched from January through May, Texas was the focus of international attention as Republicans tried to push through what voting rights groups and Democrats labeled voter suppression and Jim Crow 2.0, a reference to state laws, especially in the South, that discriminated against Blacks from the 1870s until the 1960s. In its final iteration, the proposal contained eleventh-hour provisions that would have limited Sunday voting and made it easier for judges to overturn elections. After Democrats left the Capitol during the final days of the session to deprive Republicans of the quorum required to pass legislation, the bill died and Governor Greg Abbott quickly called the Legislature back for the thirty-day special session currently underway.

Ultimately no Republicans involved in the crafting of the bill took responsibility for the last-minute additions, but leaders in the House and Senate pledged to keep the objectionable Sunday-voting and overturning-elections measures out of any future legislation. Less noticed were other flaws. First during the regular session and then again in the ongoing special session, the authors of the “election integrity” legislation increasingly weakened crucial guardrails protecting the security of mail ballots. In addition to the new ID-matching requirements, it now contains a flawed way for voters to “cure,” or fix, a rejected mail-in ballot.

Enrique Marquez, spokesperson for House Speaker Dade Phelan, declined to answer questions about why the House moved the bill forward without addressing the ID-matching and curing issues, nor would he say whether there was any specific plan for addressing these issues if the House Democrats return to Austin. “There are no bills that can be considered on the floor until Democrats return home,” Marquez wrote in an email. “However, House Bill 3 author Andrew Murr has repeatedly stated he will work with all his colleagues to make the best bill possible.” (Murr’s chief of staff said Murr was aware of the problem and “looked forward to working with colleagues about remedying concerns about how differing numbers could result in a ballot not being counted.”)

Davis said many Republicans have failed to listen to the complaints of election officials, ignoring suggestions for improvements to nonpartisan, process-related issues. “It’s just like ‘Who is steering this bus?’” Davis told me. “They are following the pattern of only listening to their ‘the steal is real’ base and not consulting with any county elections officers.”

Davis said that while he decided to testify before the House, he chose not to give testimony before the Senate because Bryan Hughes, a Mineola Republican who chairs the State Affairs Committee, had brushed him off so many times before. Davis said he reached out to Hughes’s office about the ID-matching problem multiple times, but never received confirmation that a fix was in the works. Two legislative staffers, one working for a Republican and one for a Democrat, confirmed that the Texas secretary of state’s office had also advised legislators that the ID-matching provision needed to contain a failsafe for voters who do not have both numbers in the registration system, but the changes were never made. The staffers requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak about negotiations. “Why are [election administrators] going to waste our time testifying?” asked Davis, who was appointed to his nonpartisan job by the Williamson County Commissioners’ Court. “They don’t care what we have to say. They haven’t from the beginning.”

County election administrators say the ID-matching provision imposes significant burdens on their offices, and they are unclear how to enforce it. Under the new language, the ID number—either a partial Social Security number or a driver’s license number—would have to be written on the envelope, forcing counties to spend thousands of dollars redesigning envelopes in order to accommodate a privacy flap that poll workers would peek under to check the number. “We’ve joked about whether it should be a scratch-off,” Davis said. If poll workers make an error or if voters, for example, transpose two numbers by accident, the application would be rejected with little opportunity for the voter to address the problem. “We don’t have time for that,” Davis said. “We’re getting down to registration deadlines by the time we receive a lot of these. There’s no time for the voter to mail another one.”

Texas Monthly and the nonprofit election-integrity news project Votebeat, who are jointly publishing this story, asked for interviews with Abbott, Hughes, House Elections Committee chairman Briscoe Cain, and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, but none responded by press time. Republican representative Travis Clardy, who sits on the committee hearing the election bill in the House, said he preferred to deal with the problems once the proposal reaches the full House. “My expectation was and is—if we are able to establish a quorum again—that [the fixes] would be something we would consider,” he said. “I don’t see anybody getting locked up on that.”

There are other potential deficiencies in the ballot security measures buried in the legislation, despite GOP pledges to make elections more secure and safe from fraud. One of the most common security measures for protecting the integrity of the mail-in ballot involves signatures. Under current Texas law, voters must sign the envelope they use to send in their ballot. Then a committee of untrained volunteers recruited by the local election administrator reviews the signature to see if it matches the signature on file with the county. If the committee decides the signatures don’t match, the ballot is immediately rejected. There is widespread recognition that the lack of an appeals or correction process—or “ballot curing”—is an oversight in Texas law and the courts have pressured the state to join the eighteen other states that allow ballot curing.

In May, during the regular session, both Republicans and Democrats agreed to add a provision to the election bill, now in the special session version, which creates a ballot-curing process but contains ambiguous rules and few options for voters. It’s also unclear whether this process would be extended to absentee ballot applications rejected for ID mismatches—even as legislators put far more emphasis on matching those numbers than on matching signatures. The current special session version of the elections bill allows ballots and applications whose numbers do match to skip the signature-verification process entirely. But what happens if the numbers don’t match? The ballot is immediately rejected, and the bill is unclear on whether voters can appeal those rejections. “They created this new language on curing ballots, but we may never get to that step,” said Davis. In other words, Republicans built contradictory provisions into their bill—whether intentionally or unintentionally—creating a solution to a problem that may no longer exist while also creating a new problem.

“Curing is critical to security,” said Tammy Patrick, a mail-ballot expert and senior adviser to the elections project at the Washington, D.C.–based Democracy Fund, a foundation aimed at improving the democratic process. Allowing voters to correct rejected ballots is obviously beneficial to voters. But it also allows election workers to determine if a mismatched signature is evidence of fraud or an innocent mistake. If there is widespread voter fraud, as many Republican officials believe, then the ballot-curing process could help root it out, though election administrators say they are far more concerned about a rash of needlessly rejected ballots.

“I used to make those calls [in Arizona] and every time the answer was that they had just suffered a stroke or their arm was in a cast or they signed the envelope on the dashboard of the car while driving to drop it off,” Patrick said. “It was important to know why those signatures mismatched rather than leave that question unanswered.”

The bill’s current ballot-curing language differs slightly between the House and the Senate. While the House version indicates that counties must institute a process for curing rejected ballots, the Senate’s version makes the process optional, eliminating the ability to achieve consistency among counties—one of the major motivations for House Republicans. “Consistency and clarity was the goal,” said Clardy. “It should be the same in every county.”

Both bills provide few options for voters to appeal the decision to reject their ballots. One option allows local officials to mail the suspect ballot back to the voter, who would then send in a corrected version—a shaky prospect, especially for voters who are out of state at election time, given the U.S. Postal Service’s slow delivery performance in recent years. Another option allows voters to return ballots in person, which would not be possible for homebound or far-flung voters. Other states such as North Carolina and Arizona allow far more options, including resolving the matter over the phone or by email.

Several Republican House members including Clardy, Charlie Geren, Jacey Jetton, and Matt Shaheen, said in interviews that they’d prefer the ballot-curing provision be mandatory. Clardy called the opportunity to appeal a rejected ballot a “fundamental issue of fairness.” He added: “This is one of those areas—and I’m glad you pointed it out—that we would want correcting language for.”

But it’s unclear why the authors have designed a ballot-curing process that focuses so much on signatures. After all, if the current proposal becomes law, “signature matching goes the way of the dinosaur” anyway, said Davis. Election administrators, including Davis, said they do not understand how the ID-matching section will impact the ballot-curing process, or how many ballots might even make it to the newly crafted curing process at all. No legislator was able to explain it either.

This article is a collaboration with Votebeat, a nonprofit news outlet focused on voting access and election integrity.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Lege