Editor’s note: Christopher Hooks is taking stock of the Republican and Democratic parties’ electoral prospects in complementary pieces. Read his take on the Democrats here.

Boy this has been a weird year, huh? The most interesting election the state has seen in decades is underway, and I’ve been stuck at home. (Sometimes I put on pants.) COVID-19 has turned all of us into spectators: What’s happening in the world is taking place away from us, mediated through a screen. It can feel like watching a season of a poorly written television show.

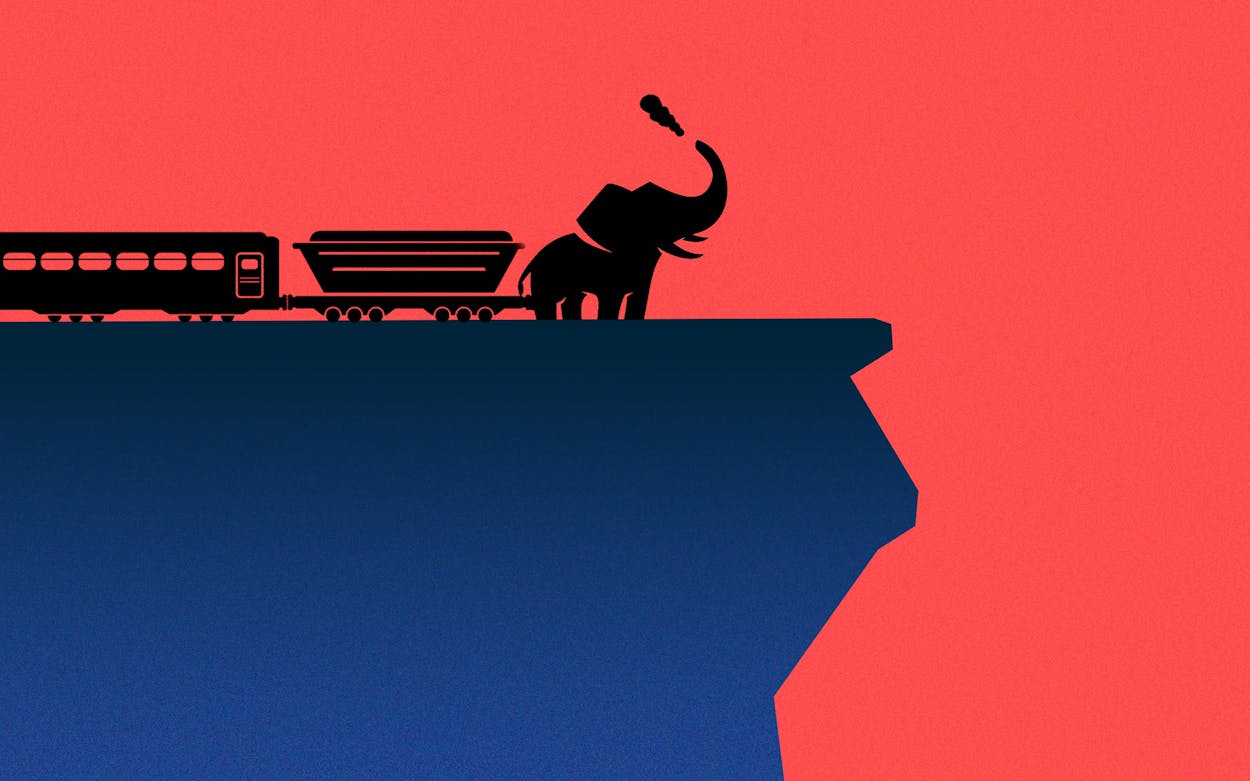

There’s one subplot the writers can’t seem to put to bed: Historically a juggernaut that builds memorials from the skulls of its enemies, the Texas GOP, which has run the state since I was in pre-K, has had a spectacularly rotten year. It’s not just the circumstances in which the state party finds itself—a deeply unpopular Republican president, a sour economy, a pandemic—it’s also that its leaders and loyalists seem hell-bent on self-harm.

Over the last year, the newly minted Speaker of the state House, Dennis Bonnen, was destroyed by a bizarre scandal. Governor Greg Abbott got lost in the coronavirus swamp, taking heavy fire from both sides and igniting an insurgency within his own party. Former Florida congressman Allen West took over the party, which he seems to be using as a platform for promoting his own brand and attacking his party’s own governor. And Attorney General Ken Paxton, already under indictment for securities fraud, saw his own second in command accuse him of taking a bribe from a political donor.

Misfortune at the top was accompanied by dysfunction below. A trail mix of misbehavior from local party officials and activists has kept the state GOP consistently in the news for the wrong reasons. And party infighting has grown louder. While it’s certainly still possible, if not probable, that Republicans will hold together on November 3—delivering Texas for Trump and holding the state Senate and John Cornyn’s U.S. Senate seat—the Texas right looks like a hot mess at the moment.

The story of the GOP’s very not-good year starts on November 6, 2018. During the midterms, Beto O’Rourke came within 2.6 percentage points of beating Ted Cruz, Democrats picked up two congressional seats in Texas, and flipped twelve seats in the Texas House. Their poor showing delivered a clear message to Republicans. President Donald Trump had become a liability in the Texas suburbs, in places that had traditionally voted reliably for the GOP. This posed a problem. There might still be enough base Republican voters to win statewide races, but in order to keep control of the state House, and with it complete control of state government, the party needed to compete in these areas. To do so, they needed to come up with a “brand” for the party that was distinct from Trump.

In the 2019 legislative session, they mostly succeeded. The most right-wing voices took a step back, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick among them. Gone was the squabbling over social issues such as the “bathroom bill,” which almost subsumed the 2017 session. The House Freedom Caucus, populated with the party’s tea party types, fell apart. The chamber’s new Speaker, Dennis Bonnen, formerly a hatchet man, adopted an amiable and patient new tone, emphasizing bipartisanship and a focus on the state’s big issues. (He even made a Democrat the Speaker pro tem.) The session last year was downright boring to cover, with a shortage of the excess and malevolence that typically characterizes the Lege.

The Eighty-sixth Legislature culminated in May 2019 in a touchy-feely press conference on the lawn of the Governor’s Mansion to tout the deliverance of a big school finance package. Abbott’s golden retriever, Pancake, attended. Who doesn’t love a big fluffy dog? Who doesn’t love schools? It included some measures intended to slow property tax growth. Who doesn’t hate property taxes? If he could have, the governor would have marshaled an army of cute little woodland animals to escort audience members to their seats. This was the softest touch we had ever seen from this generation of GOP officials.

It didn’t matter that the package wasn’t tied to a source of funding, and therefore had all the durability of a sand castle in a storm drain. The legislation sounded great on local news broadcasts. More important, it allowed incumbent Republicans, even the most right-wing ones, to run ads saying they had fought for more school funding. (Indeed, this election season has seen a plethora of visually similar ads featuring b-roll of spare modernist classrooms that don’t much look like the ones found in Texas. Invariably, the ads make the case that the incumbent, no matter how useless, was the prime mover of the whole deal.) Millions of dollars were pumped into Bonnen’s PAC to defend Republican incumbents. They had a plan and a message. The stage was set.

Then Bonnen built himself a spike pit and jumped into it. A faction leader of the party’s far right, Michael Quinn Sullivan, accused Bonnen of offering him an inducement—letting Sullivan’s lobbying group onto the floor of the House as if it were a news organization—if Sullivan agreed to target ten Republican incumbents in the primary and leave the rest alone. It seemed implausible at first. Bonnen spluttered without actually denying it. Sullivan soon announced that he had secretly recorded the meeting. Rumors started to fly about what else Bonnen had said. From late July to October 2019, when Sullivan finally released the tape, Bonnen dangled. He finally announced that he would not run for reelection.

Bonnen’s spectacular fall isn’t the sole reason the GOP is struggling—the scandal didn’t make it far into the public consciousness (despite my best efforts). But it left a leadership void. Bonnen was supposed to use his deep pockets and savvy to defend his majority. Who would take charge of the GOP’s defense of the state House? Who better than Greg Abbott, the most popular Republican in Texas, with $38 million in campaign cash?

This seemed like a good plan—until COVID-19 hit. Abbott’s governorship has been almost completely consumed by the pandemic response. And while he got a small bump in the polls in the spring, as other governors did, his approval rating has declined worryingly. Those falling numbers are the result of dissatisfaction from both the left and the right. Democrats are frustrated with the ineffectiveness of the governor’s pandemic response, while some Republicans are angry with Abbott for going much too far with his executive orders. An uprising by rebel hair-salon queen Shelley Luther—an irrepressibly Dallas-y Robin Hood and member of a dueling pianos act—led the governor to flip-flop repeatedly about what he wanted to happen, backing himself into a series of contradictory positions. At times, you almost felt sorry for him. He was reduced at one point to offering a sort of riddle to county judges in the form of an executive order that allowed local officials to crack down on mask scofflaws without telling them explicitly they could. It was a bemusing episode that left heads cocked around the state.

Abbott and other Republicans have tried hard to create buzz on issues likely to play well in suburban districts. Particularly, he’s promised to defend the police against “defunding.” But the scale of the current crisis has effectively neutered his ability to change the conversation.

What about the other statewide leaders? Agriculture commissioner Sid Miller recently appeared at a protest at the Governor’s Mansion, condemning Abbott. Patrick won the most attention he’s had all year when he went on Fox News and told a national audience that he believed many senior citizens, like himself, should be “willing to take a chance on [their] survival” so their grandkids could avoid a lockdown and not “sacrifice the country.”

Then there’s Ken Paxton. A week before early voting started, news broke that much of the senior leadership of the attorney general’s office had resigned en masse. The seven top aides recommended that Paxton, who has been under indictment on unrelated felony charges virtually the whole time he’s been in office, be investigated for bribery and abuse of office relating to actions he allegedly took to protect a friend and campaign donor, Austin real estate investor Nate Paul. The timing was perfect: Paxton had opined frequently in the previous months, sometimes alongside Abbott, that he and his party were the last-ditch defenders of law and order.

But the dysfunction hasn’t been limited to elected officials. For weeks, Republicans struggled to deal with an outbreak of racist and anti-Semitic sentiments aired by county party chairs and activists. After George Floyd’s death, incoming Harris County GOP chair Keith Nielsen posted a Martin Luther King Jr. quote over an image of a banana on Facebook. Abbott and Patrick asked Nielsen to step down. Nielsen at first indicated he would, then changed his mind. U.S. representative Kevin Brady, who represents Conroe, called him a “bigot whose word is no good.” Nielsen took office, and is helping direct GOP election efforts in one of the most diverse counties in the nation. Other county GOP chairs—quite a few of them—voiced the opinion that Floyd’s murder was a false flag operation, perhaps perpetrated by the liberal Jewish megadonor George Soros.

When it came time to hold the state GOP convention this summer, party activists insisted it be held in person—during what was the high point, so far, of the pandemic in Texas. Ultimately, the mayor of Houston and the courts prevented them from meeting in person, as was entirely predictable. The convention was a comic disaster that further alienated grassroots conservatives and helped lead to an angry party base kicking out party chair James Dickey and replacing him with tea party celebrity Allen West, who was forced out of the Army after he staged a mock execution of a prisoner in Iraq, before becoming a one-term congressman from Florida.

West set about using the position of party chairman to raise the profile of Allen West. Three days before the start of early voting—with so much on the line for the party—West took to the steps of the Governor’s Mansion, at a rally with Michael Quinn Sullivan and Sid Miller, and condemned his party’s own top elected official as a tyrant for his actions during the pandemic, as people in the crowd chanted “Allen West for governor.” It was a far sight from that happy day on the lawn of the Governor’s Mansion when Abbott, Bonnen, Patrick, and Pancake got together.

West’s new motto for the party: “We are the storm.” That’s meant to sound menacing, or cool, or tough. But another meaning can be inferred.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Joe Biden

- Donald Trump