Texas, a friend used to say, is hard on women and little things. I’ve been reminded of that observation again and again when reporting seemed to bear it out. In 2015 I listened to a caregiver testify in court, via telephone from a hospital, that state cuts to the Medicaid acute-therapy program were having disastrous consequences for her child’s incurable, debilitating genetic disorder. In 2021 an eleven-year-old boy in Conroe died from carbon monoxide poisoning, after seeing snow for the first time, as his family struggled to keep their home warm amid the collapse of a gravely mismanaged electrical grid. And then there were the perennial horror stories from the state’s spike pit of a child welfare system: a three-year-old found dead, bleeding from the ears, after his day-care provider repeatedly warned state agents about signs of abuse by his guardian; a teenage girl who killed herself when her caretakers disregarded orders not to leave her on her own; and countless others to whom the state administers heavy doses of psychotropic meds before kicking them out onto the streets at age eighteen.

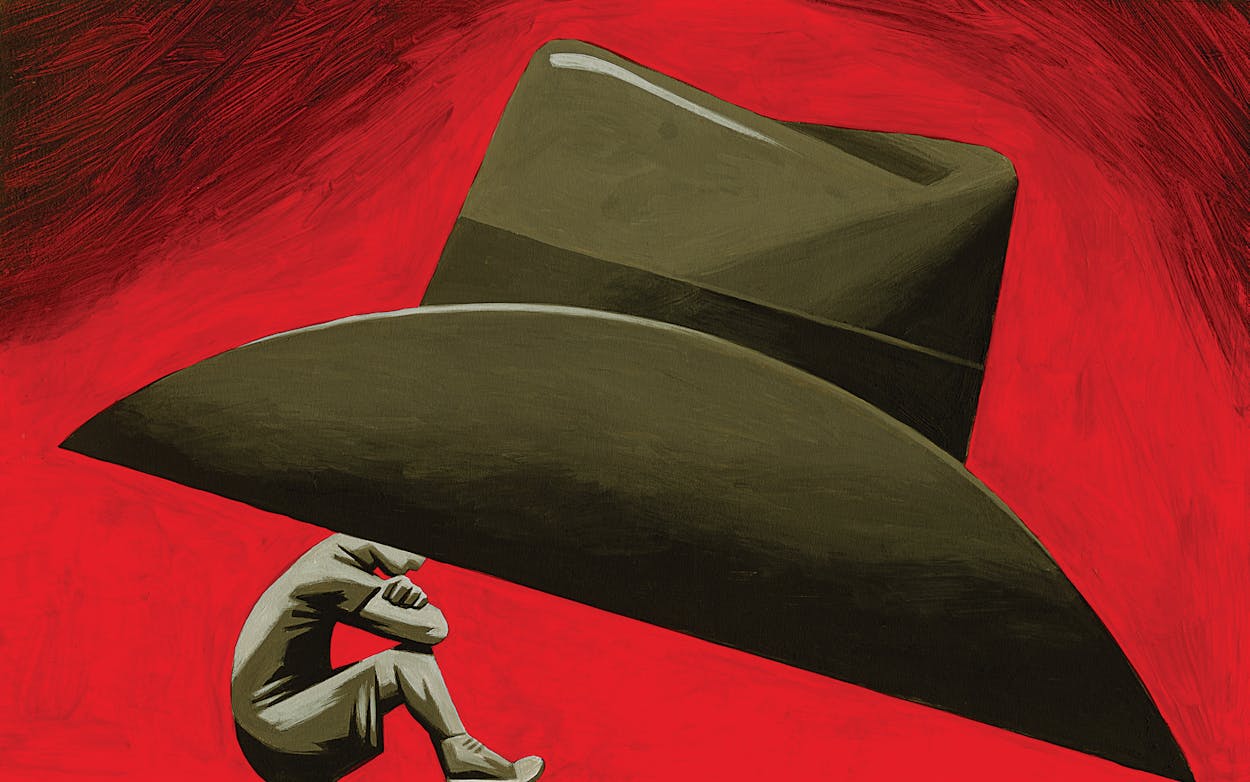

Each new revelation of misery brings a new wave of revulsion, but—I hate to say this—as you learn more about how the social safety net works in Texas, that revulsion starts to fade. It becomes a dull undercurrent instead of something sharp that pokes through. As it fades, so comes the realization that it has faded in the same way for those in power—and that nothing gets fixed because leaders, to an even greater degree, have been immunized from caring. The grid remains unsteady; children in foster care still get abused. Lawmakers make a show of passing partial, temporary fixes. The Legislature, with all its self-regard and jocularity and pride, turns out to be suffused with a very dull and banal kind of evil.

On May 24, though, something poked through. For me, it wasn’t the news that there had been another school shooting. Who could be surprised by that? Every detail was familiar. A once-bullied eighteen-year-old, two assault rifles, 21 dead, and 17 injured. What shocked were the pictures of the dead when they were alive. They were so little! Do you remember what it was like to have a body that small? A bullet fired by an AR-15 exits the muzzle at three times the speed of one fired by a handgun, shattering bones and pulverizing organs. It “looks like a grenade goes off in there,” a trauma surgeon told Wired. Parents had to submit DNA samples so their kids could be accurately identified.

This spectacular violence, it sometimes seems, has not left much of us. At his initial press conference, Governor Greg Abbott wore his traditional white disaster-response shirt and offered details of the massacre as if reading a weather report. The next day, at a second conference, the governor appeared alongside U.S. senator Ted Cruz and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and told Texans that the carnage “could have been worse.”

Appearing on Newsmax TV on the day of the shooting, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton suggested that more armed citizens at schools would help, “because it’s not going to be the last time.” Can you believe that was the response of one of the most powerful elected officials in the state to a mass murder of fourth graders? There used to be at least a perfunctory mourning period, a few hugs given in front of cameras, before those in power turned to one another and shrugged. But in truth, our leaders are only handling the Uvalde tragedy the way they do the foster care system and every other death trap run by the state. The revulsion dulls, the novelty fades, and the unconscionable becomes normal.

The Uvalde shooting happened the day of the Texas primary runoffs. The composition of the Legislature and the rest of the state government for the next two and a half years was set that night, barring extraordinary circumstances, by the conclusion of the Republican primary, which in Texas is more influential than the general election. Paxton, who’d worn a campaign shirt as he shrugged off the shooting on Newsmax, won renomination and almost certainly a third term in office.

It is a grotesque and cruel irony that the Republican primary this year, like several years of political activity before it, was dominated by an all-consuming and comically misdirected argument about the protection of children and by a multifront war against long-neglected public schools. There were essentially no contested policy proposals in the GOP primary that would affect the practical and economic circumstances of all Texans. (There rarely are.) There was, however, ceaseless discussion about the well-being of children, their morals, their internal lives.

The most acute panic was over transgender children. In February, Paxton’s office issued a formal opinion holding that gender-affirming care, such as the prescription of puberty blockers to trans kids, constituted child abuse. Shortly after, Abbott tasked the Department of Family and Protective Services, an overworked and underfunded agency he had overseen for close to eight years, with investigating the families of trans kids for such abuse.

The more widespread crisis concerned books. This panic was conjured up by right-wing parents and elected officials in roughly equal measure. The first target was “divisive” material about race. Then, elected officials began to agitate about “pornography” in schools, a category that included mostly literature featuring queer characters. Lawmakers proposed lists of books to be banned. In November, Abbott ordered the Texas Education Agency to investigate cases of pornography in public schools and prosecute those responsible “to the fullest extent of the law” because, he wrote, it had to be a top priority to “protect” Texas students.

Public school teachers and children’s librarians—members of two professions that offer highly beneficial services to society, for little pay—became villains to activist parents and candidates alike. They were called “groomers” and “pedophiles” on social media. In Granbury, near Fort Worth, two women lodged a criminal complaint in May against the local school’s libraries, prompting a police investigation. At a subsequent school board meeting, one of the women opined that a committee assembled to review troublesome books comprised “too many” librarians instead of “people with good moral standards.”

The deterioration spread. A record number of schoolteachers, already weary from the COVID-19 pandemic and now beset with a sort of siege, started quitting en masse—risking their licenses, indicating they probably wouldn’t be coming back. “I’m tired of getting punched. It shouldn’t be like this,” ninth grade math teacher Gloria Ogboaloh told Texas Monthly in March. As more teachers left, the quality of life for remaining educators declined. Then, just four months after ordering that libraries be investigated, Abbott directed the TEA to create a task force to investigate why so many teachers were quitting.

A year of manufactured outrage about the specter of loose morals in public education had the effect of making all of public education worse—which, for some, seemed to be the goal. Test scores have dropped. Even parents who strongly favor public schooling have begun to search for alternatives. State leaders, including Abbott, who have presided over an education system that spends about 20 percent less than the national average on each student, began to lay the framework for a renewed push to expand school choice and perhaps introduce a voucher system in which taxpayer dollars would be used to fund private schools.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Robb Elementary School massacre has become another club to beat public schools with, under the guise of protecting children. The day after the shooting, a Texas-educated writer in the conservative publication The Federalist wrote that parents “can’t trust government schools [to] safeguard your children from harm” and that they should “do [their] best to prevent them from being sitting ducks at frequently targeted locations such as schools” by homeschooling them. Separate yourself from whatever feeling of familiarity you have with this line of thinking. Had you read it about another culture, would you not consider it evidence of precipitous societal collapse?

It’s a tragedy that a moral panic has made the lives of Texas children worse, and their futures dimmer, by weakening schools. It’s another tragedy that the time spent fighting over library books has sucked oxygen from the discourse when so many of our kids are suffering. Not because of books in which boys kiss, or because their classmates wear dresses instead of pants, but because this has been a universally difficult and traumatic time for kids.

The children who died in Uvalde spent the last quarter of their lives in a global pandemic that has put pressure on everyone. Nearly 90,000 Texans have died, which means many young Texans have lost a teacher, a grandparent, or even a parent. Many of their families have been uprooted by the economic dislocations of the past few years. The political upheavals over that same period have been frightening even to adults, who talk in hushed tones about the future of the republic.

Children of all ages in the state may also have been scarred by the experience of the 2021 freeze, which left a deeper impression on most of us than folks outside Texas might be able to understand. Older kids know that an unstable climate and a warming planet are their inheritance. On top of all this, there are school shootings. Even students at schools where shootings haven’t yet occurred see vendors selling bulletproof backpacks, and some architects design buildings with limited sight lines and a surfeit of hiding places, taking cues from medieval fortresses. Baby boomers had duck-and-cover drills, horrifying in their own way. But the atomic bomb was an abstraction: the drills would have taken on a much different tone if every six months or so a Soviet ICBM had actually fallen near a random American school.

We ask children, on a regular basis, to rehearse being hunted, as a prophylactic against the real chance that they may someday be hunted. It can’t be hard for those who participate in the drills to imagine how it might feel to have their internal organs pulverized or to see that happen to their friends. How can anyone be expected to live this way, let alone a fifth grader? We should remember that the seventeen-year-old shooter at Santa Fe High School and the eighteen-year-old shooter in Uvalde likely grew up taking part in their own mass-shooting drills. We have to help children who are similarly troubled. But instead, our state has spent the past year talking about which library books to censor.

A very simple way the government could assist students is to ensure that schools are equipped with figures whose primary job is not teaching but looking after the well-being of kids. Would you like to know an ugly fact? If you attended a Texas public school decades ago, you may have a strong memory of a school counselor or a guidance counselor. Today, state law requires only that school districts have one such counselor for every 500 elementary students. Groups such as the Texas Association of School Boards take the downright indulgent view that there should be one counselor for every 350 students. Imagine being tasked with searching for signs of suicidal behavior, or sexual abuse, or the compulsion to hurt others, or simply overbearing sadness, in a crowd of 350 children. Some social scientists, for what it’s worth, think we have the ability to meaningfully know some 150 separate individuals.

Most state leaders, it seems, believe that none of the problems of our schools—or our foster-care system or the state’s health-care system—have anything to do with them. They behave as if they lack the power to materially change lives for the better. But they’re mistaken. There’s a profound poverty of imagination in the Legislature. If a committee chair takes the gavel when state law requires one counselor for six hundred students and moves the standard to five hundred, leaders celebrate themselves for being

forward-thinking reformers. There’s often also a profound refusal to accept responsibility. When a new employer comes to Dallas, state leadership is happy to take credit. But when the state’s children are suffocating—perhaps literally, for those affected by the decapitation of the Medicaid acute-therapy program—that’s the result of multiple complex factors. Don’t you think it’s a shame we no longer have prayer in school?

If Texas showed great disrespect to the Uvalde students in life—and indeed it did—then we have also disrespected them in death.

Folks further up the hierarchy, such as Abbott, content themselves with telling happy stories. At that Wednesday press conference following the Uvalde shooting, when Abbott declared that the disaster “could have been worse”—an incredibly tone-deaf thing to say about the slaughter of a fourth grade class—he added, “The reason it was not worse was because law enforcement officials did what they do. They showed amazing courage by running toward gunfire for the singular purpose of trying to save lives.”

This narrative was delivered in the manner of an animatronic robot reading an outdated script at a theme-park stage show. Indeed, Abbott’s words didn’t remotely accord with the situation on the ground. First responders did not do much running toward anything. Law enforcement stood outside the school for more than an hour while children called 911 begging for help and letting officers know exactly where the shooter was. The lead officer on the scene didn’t hear of these calls because he had neglected to bring a radio. As parents begged the police to go inside and save their kids, several officers pinned and handcuffed some of them. Abbott’s state police chief, bureaucratic trench fighter Steven McCraw, initially told the media, the day after the shooting, that law enforcement had skillfully “contain[ed the shooter] in the classroom” where students were shot—in the same way, one supposes, that a bull can be contained in a china shop. They seemed to have assumed that the children in the room were dead and that the shooter could do no more damage. But more died needlessly in the intervening hour.

State officials must have known that something was wrong with the timeline of the response when they showed up in Uvalde—parents were complaining loudly about it to anyone who would listen—but in front of the international news media, leaders displayed concerned frowns and professed that everything had gone according to plan. Days later, at a third press conference, which took place at the same time as his recorded remarks to the National Rifle Association convention in Houston, Abbott conceded that the information he had initially been given was wrong. He had been “misled,” he said, although he didn’t say who had misled him. McCraw walked back some of his earlier claims, before saying simply that the police had made the “wrong decision, period.”

If Texas showed great disrespect to the Uvalde students in life—and indeed it did—then we have also disrespected them in death. McCraw delivered his initial remarks at a press conference that Democratic gubernatorial candidate Beto O’Rourke attended in order to ask questions. Republicans were quick to decry O’Rourke’s presence as “political theater.” And of course it was. But the conference itself was also political theater: a stage play showing top men in cool command of the situation, with a happy moral to share and heroes to elevate. And of course, blameless all. They are always blameless. We are lucky to have such men above us.

One of the main progenitors of the recent agitating in Texas over transgender kids is a man named Jeff Younger. He and his wife divorced when their children were little. One of their kids is transgender and began identifying as a girl; Younger’s ex-wife supported her in taking a new name and presenting in public as female. Younger saw this as a great loss—the loss of his son—and took to the courts, at great personal expense, in an effort to gain custody and force his child to detransition. But the courts were unsympathetic.

Younger became a cause célèbre for the right and this year campaigned to represent part of the Dallas–Fort Worth suburbs in the state House, primarily on the issue of passing laws to block kids from transitioning. He brought much of the state GOP along with him. On the night of the Uvalde shooting, Younger lost his runoff to Ben Bumgarner, who co-owns a firearm company that produces modified AR-15s.

There’s a story Younger likes to tell. It’s terribly sad, although not in the way he intends. As a child, Younger had no father in his life. “My mother had exiled him by divorce when I was eight years old,” he wrote in the Eagle Forum Report, a newsletter published by the late conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly’s group. Younger recalled that he would sit in a ditch outside his house. “With a stick I would spell my father’s name in the dirt. I would sit there all day, waiting for my father to come back.” His missing dad haunted him into adulthood. Eventually Younger found his dad, a deflated man, he says, with whom he then had to cut ties again.

Younger deserves compassion for this loss. But then his story continues. His own marriage failed. He found meaning in life in the drive to “give my posterity a path to manhood in a fatherless society.” Younger believes his child has been hoodwinked by his ex-wife into wearing dresses. But in his refusal to even consider the possibility that his daughter’s desires and needs do not match his own, he cannot see that, in a way, he has abandoned his child too.

That’s a tale as old as time: the pain of one generation turning into the pain of the next. It’s the saddest story there is. And we’re all doing it. Between the Santa Fe High School shooting, in 2018, and the Robb Elementary School shooting, Texas engaged in an exhausting, degrading debate about how to protect our kids: how to make them love their country, how to make them love others in the right way. And all the while we were readying to hand them a violent, warming, troubled world. May God help the young. But let’s hope he has some time for us too.

This story appeared in the July 2022 issue of Texas Monthly. An abbreviated version originally published online on May 26, 2022, and has since been updated. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Lege

- Ken Paxton

- Greg Abbott