The Law North of the Salt Fork

“Shurf” Rufe Jordan is a lawman even a criminal could love.

Rufe and Viola Jordan have had hundreds of next-door neighbors during the 32 years they’ve lived in the two-bedroom apartment at 217 N. Russell in the Panhandle town of Pampa. But few have been appreciated as much as a nattily dressed black man named Little Possum Grice.

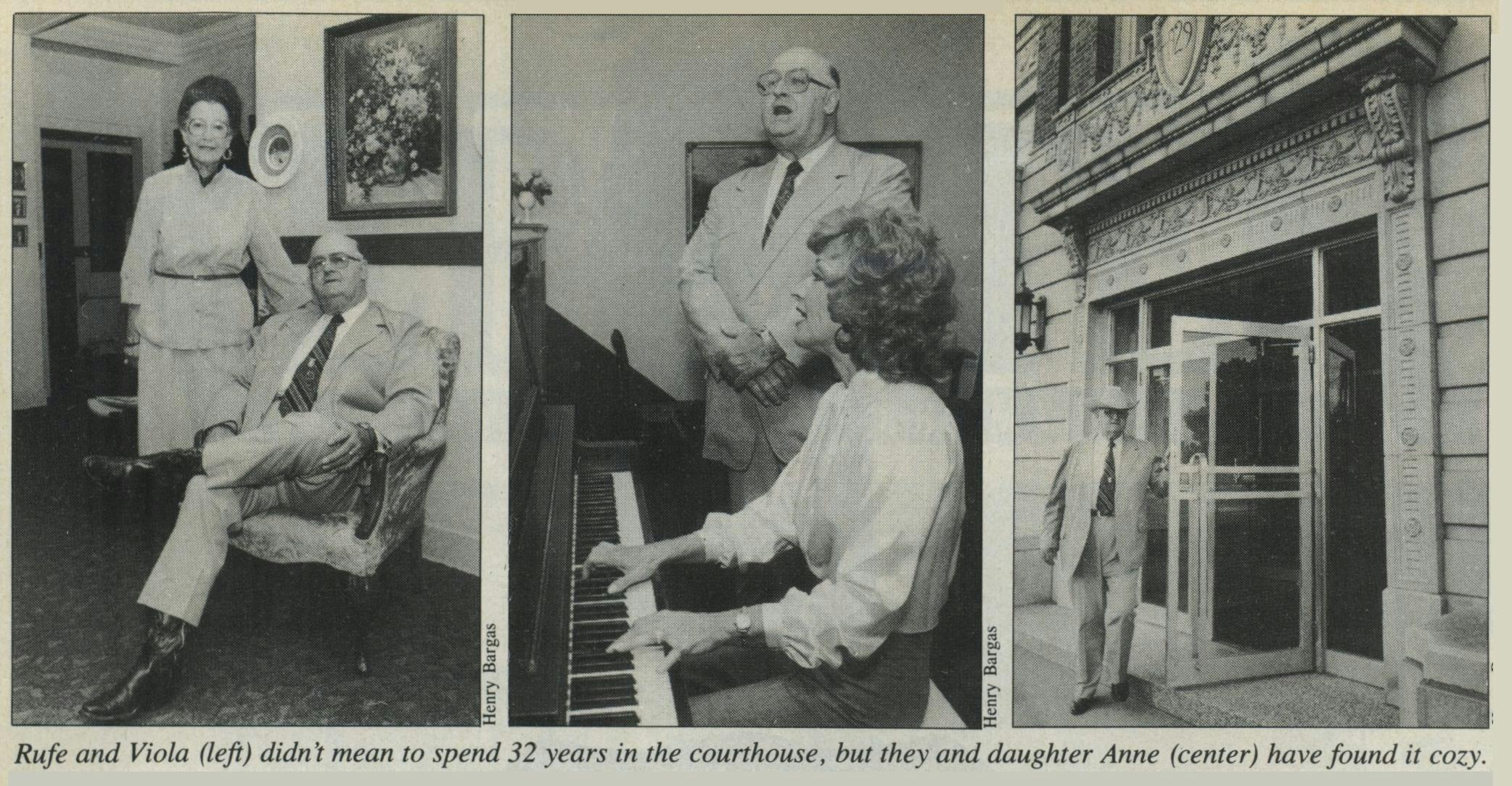

On nights when Rufe was feeling a little restless or a little low or nights when he just plain missed his daughter, Anne, who had gone off to school, he would unlock the steel door separating his domicile from Possum’s and invite old Possum over. Then he’d stand beside his upright Hallet & Davis walnut piano and sing along in a boisterous, raspy tenor as Possum picked out Rufe’s favorite Irish songs—“That Old Irish Mother of Mine,” “Mother Machree,” “Galway Bay.” After the festivities, which sometimes were the highlight of an evening of entertaining at the Jordans’, Rufe would thank Possum and return him to the jail cell next door, where he was awaiting trial for shooting Tooker Washington to death after a philosophical disagreement about a card game.

Most people charged with killing someone would probably feel a bit bewildered knocking out sentimental Irish songs while the sheriff sang along. My guess is that Possum felt nothing of the sort. A lot of adjectives fit Rufe Jordan, but “bewildering” is definitely not among them. One of the most comfortable Texas stereotypes is that of the old-style rural “shurf”: part lawman, part counselor, part local historian, part arbiter of community mores—a combination of John Wayne and an Irish parish priest. And from his imposing bulk to his traditional garb to his oddly courtly and absolutely distinctive manner of speech, there can’t be a better specimen extant than Gray County sheriff Rufe Jordan.

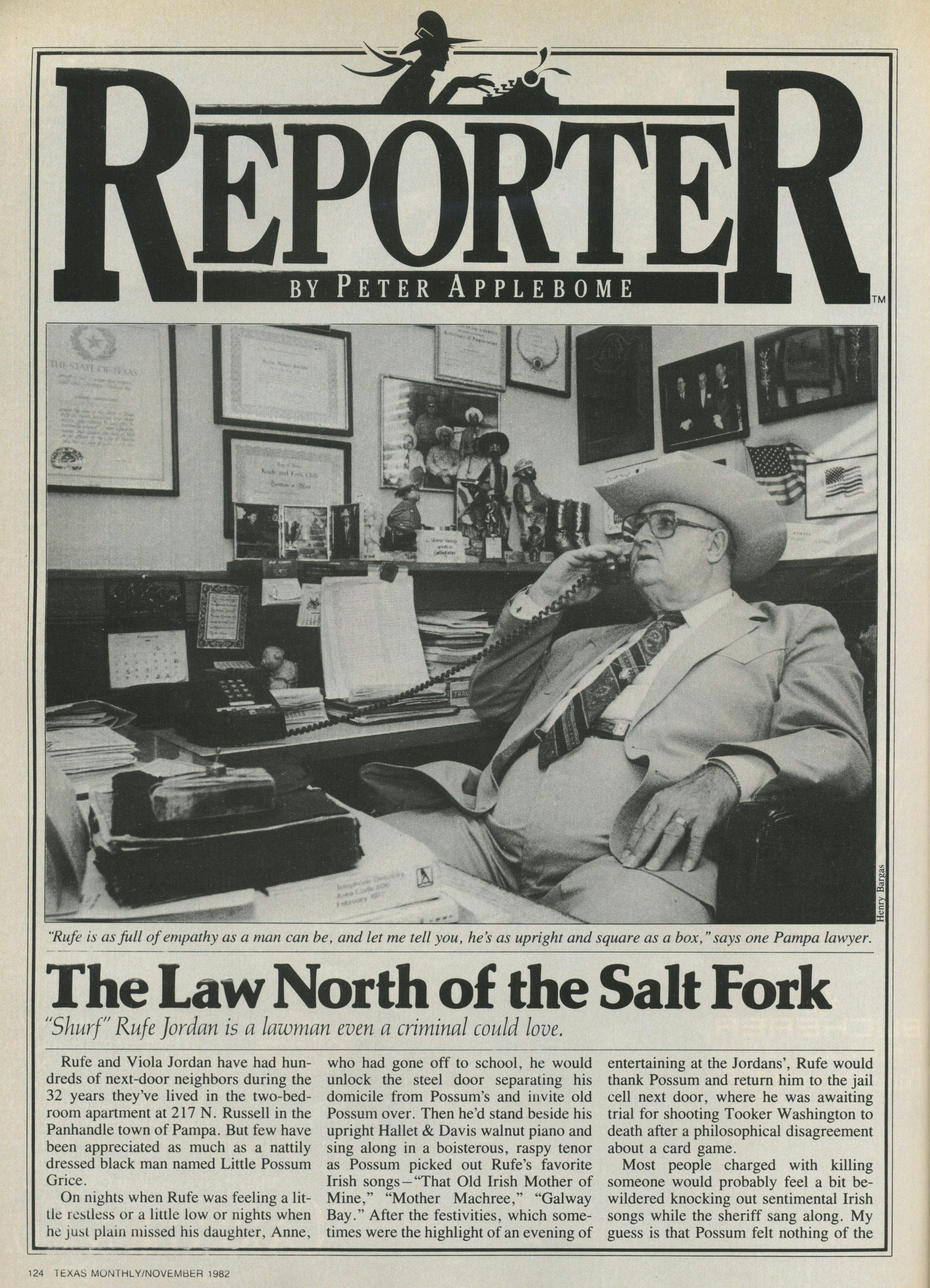

“Rufe is as full of empathy as a man can be, and let me tell you, he’s as upright and square as a box. He’s probably one of the greatest sheriffs that Texas has ever had,” says Rowdy Bowers, a well-known Pampa defense attorney. “I’ve heard speculation all through the years that Rufe was getting old, Rufe was getting tired, but he’s not. He’ll be in that job as long as he wants to be.”

Rufe didn’t plan on spending 32 years in the courthouse when he and Viola first surveyed the fourth-floor apartment there after his election in 1950. But you get the impression that he realized he might be there for a while. “ ’Course, I had never seen a jail,” Viola recalls, “so Rufe said, ‘Mother, if you don’t want to live up there that’s fine, but you won’t be by yourself as much as if we lived outside.’ And we decided that if we were going to live up there, we would fix it up like home, and that’s what we’ve done.” Apart from minor catastrophes, like the time a prisoner stole the meat from a freezer they kept in the jail, and recurrent annoyances, like the sounds of jailbirds trying to saw or burrow their way to the outside world, the courthouse has provided a delightfully normal home. By now, Viola finds it hard to imagine going home by any route other than the elevator to the jail.

The apartment itself is ruled by Viola and an eight-year-old poodle named Honey; Rufe’s domain is a gloriously cluttered first-floor office. There’s Rufe’s saddle and chaps from the Pampa Roping Club sitting on a wooden horse. There’s his hat rack with three Western hats and about a half-dozen gimme caps. There are commendations from groups such as the West Texas Chamber of Commerce and the Top O’ Texas Knife and Fork Club; pictures of his wife, daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchild; and a plaque reading, “God Could Not Be Everywhere So He Created Grandfathers.” In case all that doesn’t summon up the world of Norman Rockwell with sufficient clarity, there’s a 1971 Norman Rockwell Boy Scout calendar.

Presiding over it all is a six-foot-four-inch, 275-pound man (down from a peak of 346 pounds) with a great bald dome, who from a certain angle looks remarkably like Sydney Greenstreet doing an impression of Matt Dillon. His boots are handmade by a fellow in Clarendon, his jacket is a twill Texas Mesquite Exclusive made in Fort Worth, and his Resistol hat has a sweatband that reads, “Like hell it’s yours. This hat belongs to Sheriff Rufe Jordan.” He leans sideways, spits chewing tobacco into a brass spittoon on the floor, and begins speaking in a rolling cadence that sounds like the beginning of a sermon.

“Of course, this is my hometown, this is my home county. We have our problems, we surely do, but I think we’re very fortunate considering the things we read about,” says Rufe, who was born 23 miles south of Pampa in 1912 and whose father was a constable for the county. “But it does seem that violation of the law has been on the increase; theft of property, theft of automobiles, that’s all way up, it surely is. There was even a wedding garment taken from one of our very lovely ladies. You wonder who would ever do a thing like that.”

Rufe wanted to be a lawyer, but he couldn’t afford to stay in school during the Depression. He came back to Pampa, worked in the jail, spent thirteen years at an oil refinery, and returned to law enforcement when the refinery shut down, serving four years as chief deputy before being elected sheriff in his first bid for the office. Over the years, he developed a fondness for the cops-and-robbers aspect of his job. “The matching of wits with a known offender, trying to work these cases out, a burglary, an armed robbery, this or that—it’s a challenge, it surely is,” he says. “It has never been boresome to me.” The volume of wrongdoing keeps him busy—there’s a steady stream of petty crime, oil field theft, cattle rustling, and the like—but there’s plenty of time left over for his unofficial duties as county psychologist.

Don’t misunderstand. Rufe Jordan—who in his younger days was observed to lift the front ends of automobiles when properly worked up—will never pass for a bleeding heart. You need only hear the sharpening of his voice when he tours the jail to realize that. But a fair part of his day is taken up with what Rowdy Bowers refers to as social engineering. And it’s that side of the job that seems to get to him most. As Viola says, “I have seen him, well, not go to pieces, because he doesn’t do that, but when a judge orders him to take children away from their parents, that just unnerves him. He’d rather be whipped with a wet rope.”

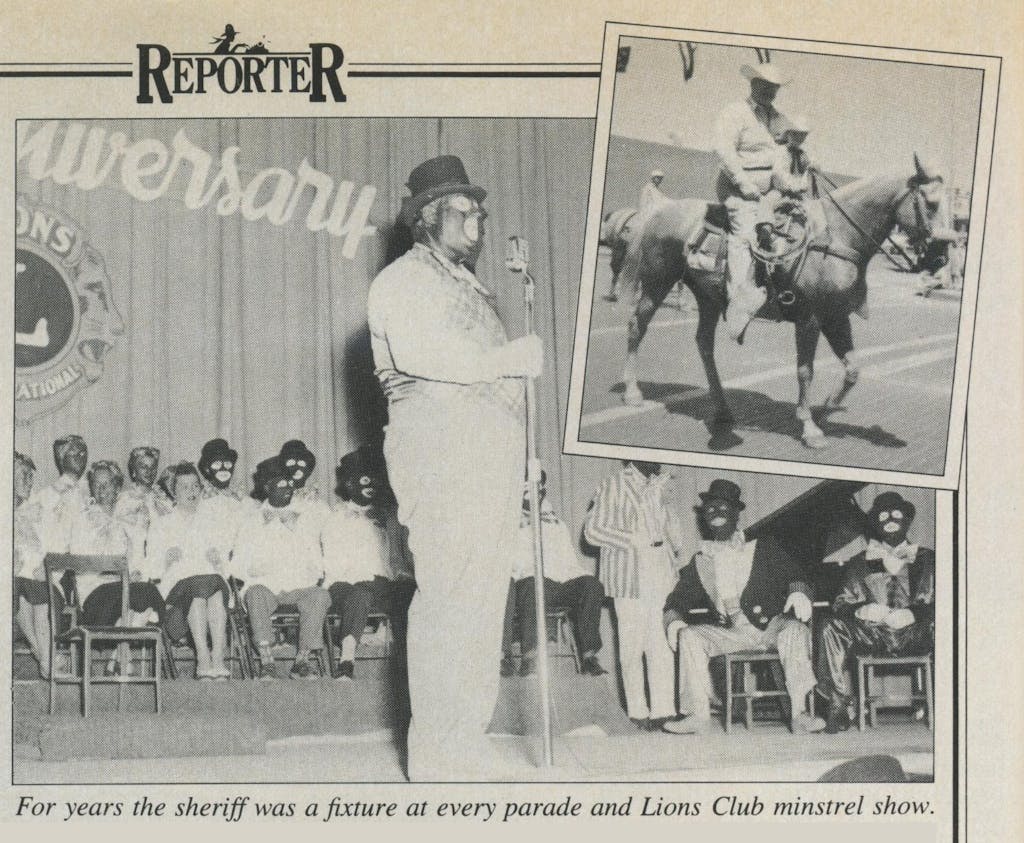

There are certain bits of Rufiana that all of Pampa knows. For many years the sheriff was the star of the now defunct Lions Club minstrel show, and everyone seems to have an indelible memory of this huge Irish tenor in blackface, a tux, and a top hat. Rufe and his palomino, Yellow Dog, were also fixtures at every local parade, and talking about the horse puts him in almost the same melancholy state as some of his favorite Irish songs.

“I rode him eighteen and one-half years, a big yellow horse, everyone knew him,” he says. “He weighed thirteen hundred pounds and was fifteen and one-half hands high. When he started to go downhill fast, they told me we were going to have to put him to sleep. So finally I said, ‘Okay, Doctor, you give me an hour’s start, put him to sleep, and we’ll never mention him again.’ And we haven’t.”

No doubt the good doctor would rather walk on hot coals than fail to honor the sheriffs grief. For what’s most compelling about Shurf Rufe Jordan is not his physical presence or even his courtly sensibilities but the remarkable affection the people of Pampa have for him. He’s precisely the kind of indomitable, larger-than-life spirit most of us long to believe in—not so much because he’s good at catching crooks as because once he’s got them, he’s likely to pull Little Possum Grice out of jail and sing “Ireland Must Be Heaven” before fading off to bed.

Invasion of the Zines

Is Texas ready for punkdom’s answer to Rolling Stone?

It’s tough being a punk in Lubbock. Just ask Robin Storey, who is most of what passes for Lubbock’s punk scene. There are no punks in her high school; there are no local punk bands and no places for out-of-town punk bands to play. Her parents are so down on punk that her mother broke her Meat Puppets and Television records. “She’d probably break them all if she had a chance,” she says. “They’re very unsupportive of it. They’d prefer me to be a Girl Scout.”

But there is one way to get by as Lubbock’s only fifteen-year-old punk: go into publishing. Unbeknownst to all of us who don’t have spiky hair, a lot of torn black T-shirts, and albums by groups like the Dead Kennedys, Smart Dads, and Bad Brains, there is an underground punk publishing network with tentacles all over Texas. Robin has put out sixteen issues of her contribution, called New Musical Excess, and there are at least a dozen other publications in Texas—and hundreds around the country—in various shapes, sizes, and degrees of dormancy or vitality.

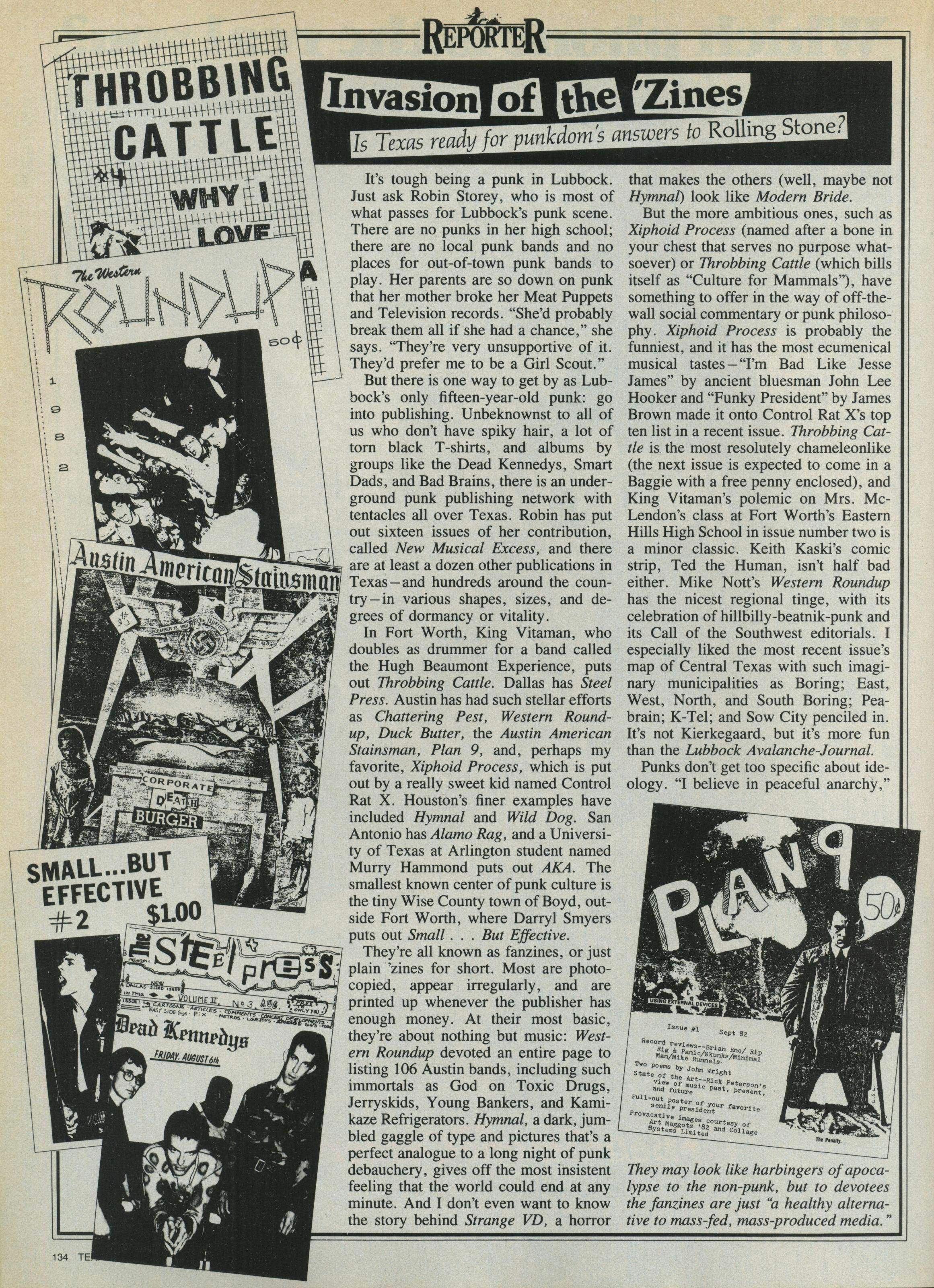

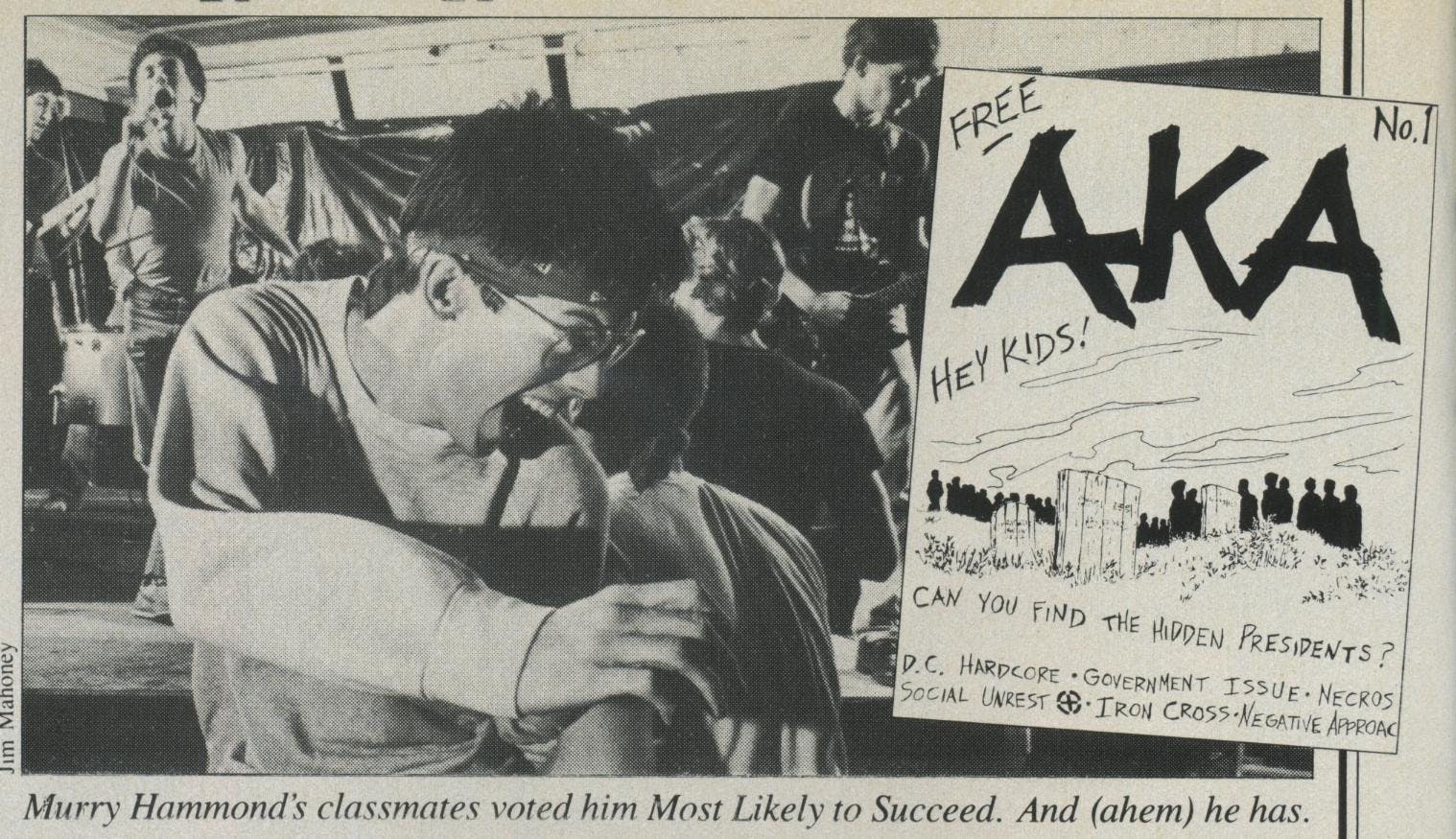

In Fort Worth, King Vitaman, who doubles as drummer for a band called the Hugh Beaumont Experience, puts out Throbbing Cattle. Dallas has Steel Press. Austin has had such stellar efforts Chattering Pest, Western Roundup, Duck Butter, the Austin American Stainsman, Plan 9, and, perhaps my favorite, Xiphoid Process, which is put out by a really sweet kid named Control Rat X. Houston’s finer examples have included Hymnal and Wild Dog. San Antonio has Alamo Rag, and a University of Texas at Arlington student named Murry Hammond puts out AKA. The smallest known center of punk culture is the tiny Wise County town of Boyd, outside Fort Worth, where Darryl Smyers puts out Small. . . But Effective.

They’re all known as fanzines, or just plain ’zines for short. Most are photocopied, appear irregularly, and are printed up whenever the publisher has enough money. At their most basic, they’re about nothing but music: Western Roundup devoted an entire page to listing 106 Austin bands, including such immortals as God on Toxic Drugs, Jerryskids, Young Bankers, and Kamikaze Refrigerators. Hymnal, a dark, jumbled gaggle of type and pictures that’s a perfect analogue to a long night of punk debauchery, gives off the most insistent feeling that the world could end at any minute. And I don’t even want to know the story behind Strange VD, a horror that makes the others (well, maybe not Hymnal) look like Modern Bride.

But the more ambitious ones, such as Xiphoid Process (named after a bone in your chest that serves no purpose whatsoever) or Throbbing Cattle (which bills itself as “Culture for Mammals”), have something to offer in the way of off-the-wall social commentary or punk philosophy. Xiphoid Process is probably the funniest, and it has the most ecumenical musical tastes—“I’m Bad Like Jesse James” by ancient bluesman John Lee Hooker and “Funky President” by James Brown made it onto Control Rat X’s top ten list in a recent issue. Throbbing Cattle is the most resolutely chameleonlike (the next issue is expected to come in a Baggie with a free penny enclosed), and King Vitaman’s polemic on Mrs. McLendon’s class at Fort Worth’s Eastern Hills High School in issue number two is a minor classic. Keith Kaski’s comic strip, Ted the Human, isn’t half bad either. Mike Nott’s Western Roundup has the nicest regional tinge, with its celebration of hillbilly-beatnik-punk and its Call of the Southwest editorials. I especially liked the most recent issue’s map of Central Texas with such imaginary municipalities as Boring; East, West, North, and South Boring; Pea-brain; K-Tel; and Sow City penciled in. It’s not Kierkegaard, but it’s more fun than the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal.

Punks don’t get too specific about ideology. “I believe in peaceful anarchy,” says Robin Storey. “That’s a real punk ideal. And the general open-mindedness of it. I think punks are real open-minded, which is different from most people here in the buckle of the Bible Belt. It’s a healthy sign of the culture, a good alternative to mass-fed, mass-produced media.”

In general, punks are against fascists, the Klan, cops, disco, hippies, preppies, New Wave music (which they see as a commercialized, sellout version of punk), making money, being poor, and being normal. And they’re really against Ronald Reagan. “I hate it with Reagan and all. He’s the main reason why there’s punks,” says RoseMary Rodriguez, who puts out Alamo Rag. “But if it wasn’t him, there’d be something else, like religion. The ones you see on TV that want money for their church—like Jerry Farewell or whatever his name is.”

They’re for short hair, bands that sound vaguely like the supersonic Concorde, the dorkiest aspects of the fifties, culture on the level of Japanese monster movies and old sitcoms, a sort of generic anti-Americanism, and each other. They seem to have an intense interest in and very mixed feelings about nuclear holocaust.

From what I can tell, it’s not much fun being a punk. Frat rats and jocks give you a hard time, parents get mad about your Dead Kennedys albums, and even the liberal media don’t have the affection for punks that they had for the rebels of the sixties. As Storey laments, “The hippies were luckier than we were.” Even punk fun doesn’t seem like much fun. I spent one awful night visiting Studio D, a punk hangout in Dallas’ dingy warehouse district that looks the way Berlin might have if a bunch of skateboarders with Mohawks had won the war. (There’s an important metaphysical link between punk and skateboarding that’s a little too abstruse for me.) Other than kids skateboarding into walls, the main attraction was the music—Youth Brigade and the Hugh Beaumont Experience. Both King Vitaman and his lead singer, the Reverend Brad Stiles, seemed like good guys, but if you took twenty bad records and played them together really loud at 78 rpm, you might get an idea of what the HBE is about. The King should stick to publishing.

Punks can certainly look ominous, and I’m told things can get pretty rough at some of the more spirited slamdancing sessions, which consist of devotees slamming into one another while doing the punk world’s answer to the rumba. But the fanzine publishers, most of whom are still in their teens, are a real nice bunch. Robin Storey wants to be a writer. Control Rat X, who first got into punk in his Latin class, wants to go into advertising. Murry Hammond was a star athlete and was voted Most Likely to Succeed at Boyd High School. “People think punks are violent. We’re not. Most of us are too small to be violent,” says Boyd punk Darryl Smyers. “I wear my spiked wristbands to Six Flags and people let me in front of them to ride the Shock Wave.”

Anyway, I still think the music stinks, but the ’zines and their publishers are okay. I’m not going to say I’d be thrilled if my kid came home with a Mohawk, but I’m glad there are some high school kids who don’t wear Izod or Polo shirts and dream of going to business school at SMU. Let’s face it, you have to be pretty outrageous to be outrageous these days, and the punks are just doing what it takes. As for why be a punk at all, the best answer I got came from Biscuit, who puts out Chattering Pest and sings for an Austin band called the Big Boys. “Why be normal?” he said. “Punk is something new that’s happening, and people got tired of hearing Jerry Jeff Walker sing, ‘I’m a drunkard’ over and over and over. It’s a trend, and if the trend were to wear a Southern-belle evening gown to the Safeway, then everyone would hop right on that, too.”

- More About:

- Music

- Lubbock

- West Texas