This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

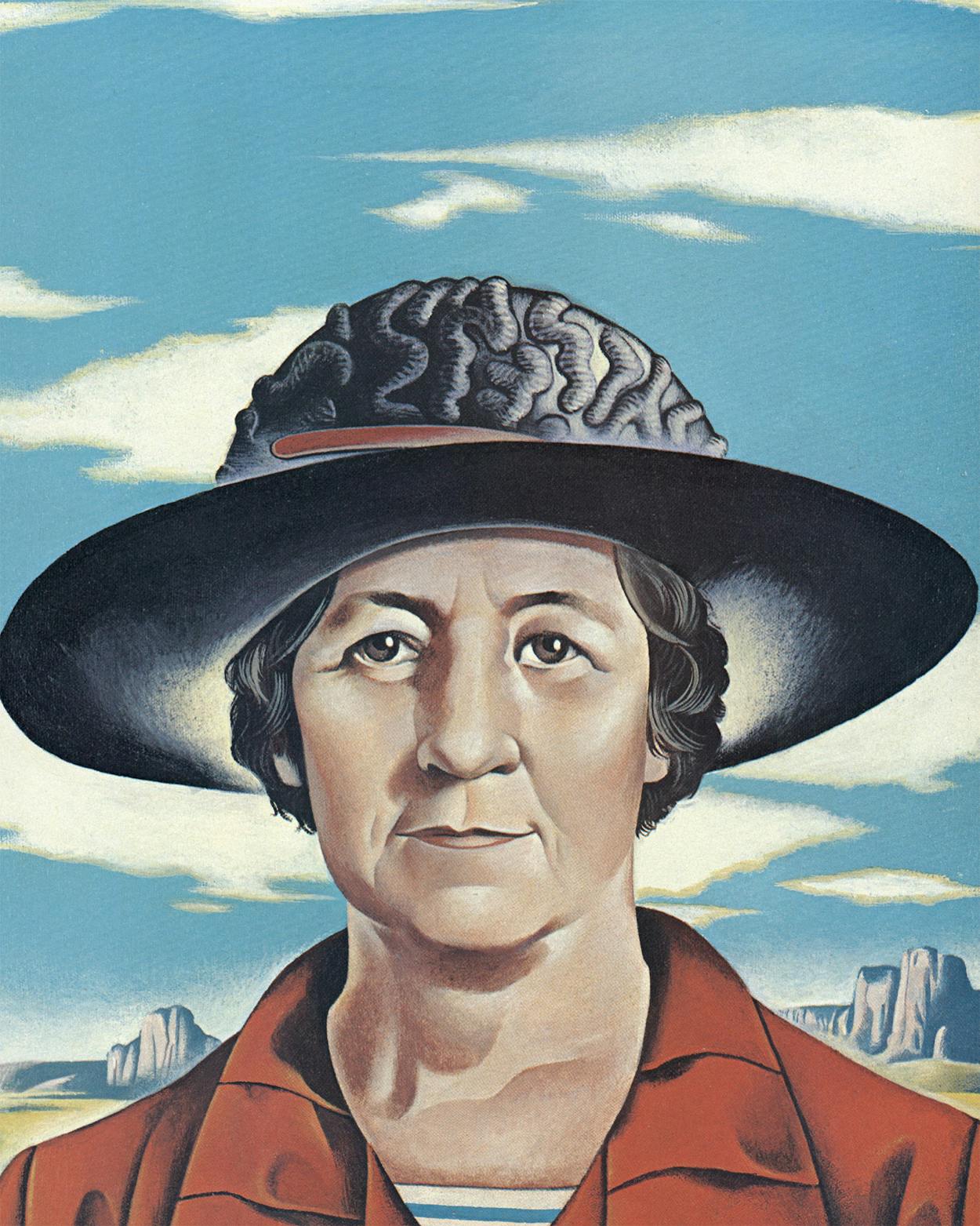

The Burpee seed company named a zinnia after Ma Ferguson near the end of her life. That may have gratified her as much as her years in politics. To place her in our time, imagine a mix of Betty Crocker and Geraldine Ferraro. In 1924, just four years after the Nineteenth Amendment gave American women the vote, Texans made Miriam “Ma” Ferguson the country’s first elected woman governor. She promised to eliminate the Ku Klux Klan as a political force in Texas, and she succeeded. The New York Times hailed her triumph as a “victory over the powers of darkness and bigoted intolerance.” Her legacy, however, was the establishment of the principle that Texans will go to extraordinary lengths to prolong the careers of politicians whose quirks they find appealing. Though her political career touched three decades, she is remembered as the ultimate figurehead, a woman who sought power only so that a man could exercise it. “She had a chance to win the admiration of the whole country,” said Edith Johnson, a prominent feminist of the time, “but as an old-fashioned slavewife, the prospect is that by her weakness she will defeat both herself and her hero, Jim.”

Miriam, a Bell County farm girl, and Jim Ferguson set their wedding date with symbolic élan—the last hours of the century, New Year’s Eve 1899. A lawyer and a banker, he ran for governor as “Farmer Jim” and won in 1914 as a protector of the rights of sharecroppers. He was accused of selling pardons to convicts; the prisons supplied cottonseed and corn for use on his farms. He vetoed funds for the University of Texas when regents stood in his way, and he accepted a $156,500 loan from brewing interests on the eve of Prohibition. In 1917 Ferguson was impeached. Barred from state ballots, he made a politician of Miriam when she was 49. During her 1924 campaign, she let him do most of the haranguing, both on the stump and in his populist newspaper. While Jim ridiculed her Klan-backed opponent, Felix Robertson, as the “Klandidate,” Miriam soaked in epsom salts an arm swollen from handshaking. A reporter dubbed her “Ma,” and slogans appeared: Me for Ma. And I ain’t got a dern thing against Pa.

At her Temple home Ma allowed herself to be photographed while she was feeding chickens and sweeping the porch, but she wore a chinchilla stole to her inauguration. As governor she wrote a syndicated newspaper column that extolled the nourishment of cornbread and turnip greens, worried about the popularity of women’s golf, and urged homemakers to choose a profession in case they needed one. Texans assumed that Pa governed by proxy. He stirred unpleasant memories, however, by sitting in on meetings of the new Texas Highway Commission—especially when attorney general Dan Moody charged that road contractors had received $7 million for $2 million worth of work.

In retrospect, Ma’s record holds up better than Pa’s. She outlawed the Klan’s use of masks in public and said that the Legislature had more important business than Prohibition. Her downfall in the 1926 campaign against Moody could be attributed to the highway scandal, as well as to her compassion for convicts. She thought that no inmate should be denied the human right to see a dying parent. Though one publication deplored the release in seventeen months of 203 murderers, 44 rapists, 10 bigamists, 402 bootleggers, and “a schoolteacher convicted of aggravated assault on little boys,” Ma believed that record was her highest achievement: “I am proud of having a heart that responds to merciful instincts and have no apology to make for granting the pardons.”

She won a second term in 1932—a time that required her to cut the state payroll by 25 per cent. An ardent New Dealer, she ran as a Roosevelt loyalist in 1940 but lost to W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel. Jim Ferguson died in 1944. Miriam lived on in Austin until 1961, growing the zinnias named after her. A yellow dog Democrat, she championed the young Lyndon B. Johnson, and with Price Daniel she defied Texas’ other ex-governors by supporting the Kennedy-Johnson ticket. Ma confronted issues—prisons, public education, failing banks, budgetary crises, a depressed economy—that dominate our state politics today. But among feminists she never achieved heroic status; she was too old-fashioned, too tied to Jim Ferguson. “What I miss a great deal,” she reminisced at eighty, “is meeting him at the door when he came in and asking him, ‘What’s cooking?’ He knew what was going on in politics and everywhere else, and he’d tell me. Now I don’t always know.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics