This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

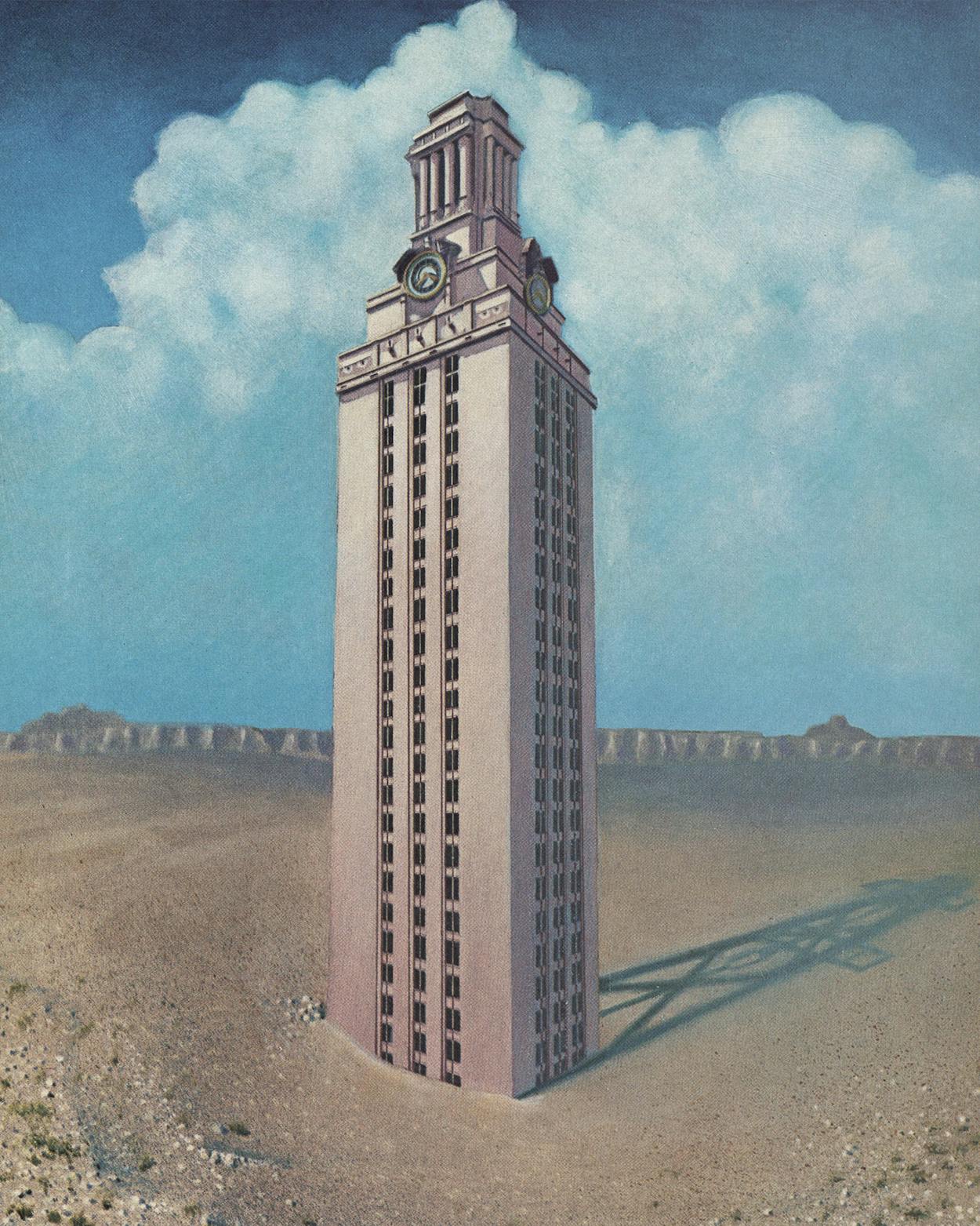

The greatest land empire in Texas is the province not of the King Ranch (825,000 acres) nor of the Temple timber companies (1.1 million acres) nor of the lesser-known but larger Texas Pacific Land Trust (1.2 million acres). It belongs to the University of Texas. In nineteen West Texas counties, from the last limestone outcroppings of the Edwards Plateau to the outskirts of El Paso, are 2.1 million acres that constitute the birthright of the university.

This vast territory is the progenitor of the Permanent University Fund, also known as PUF, which consists of income from the land. Do not be fooled by the airy acronym: PUF is so substantial that its assets today are worth more than $2 billion. That makes UT the richest public university in the country. But PUF is far more than just an endowment fund. It lies behind so much of UT’s tumultuous and controversy-filled past—the vision of its founders, the pretensions of its boosters, the frustrations of its critics, the envy of its rivals, the tragedy of its gap between potential and performance, its deep and continuing involvement in politics, its love affair with oil. In short, PUF is UT’s soul.

The reverence reserved for PUF at UT is evident in Austin, where a ceramic replica of a gushing oil well decorates the old business building, and in the brine-scarred oil fields west of Big Lake, where oil was first discovered on university lands. Just off U.S. 67 is a white stone monument erected by the university. This is not your usual historical marker; the familiar tone of official neutrality is utterly absent. “Cognizance of what took place here,” the plaque reads, “compels one to be amazed at the great goodness of providence [and] the wisdom of early Texans in setting aside land for the development of the educational system of the state.”

But more credit is due to providence than to wisdom. In 1839 Texas reserved fifty leagues of public domain (221,000 acres) in good farming country northeast of Dallas to endow a state university. In 1861 it sold everything to pay for the Civil War. Later the state constitution of 1876 reinstated the idea of a land-based endowment for what was described as “a university of the first class.” But as so often has been the case at UT, the vision was soon compromised. The state reneged on three million acres of farmland and gave UT two million acres of desert. After forty years, the total amount in PUF was less than $1 million. Then Santa Rita No. 1 came in, and in a single year PUF grew by 445 per cent.

Since Texas A&M is technically a branch of UT, the Aggies also have a claim on PUF. Before oil, though, A&M wanted no part of it. After oil, A&M changed its tune. The truce let UT keep control of PUF but cut A&M in for a third of the minerals. The split inspired the original Aggie joke:

Q.—Why did UT get two thirds and A&M only one third?

A.—A&M got first choice.

The Aggies were only the beginning of UT’s troubles over PUF. In the forties, oil barons lured to regenthood by the prospect of commanding an oil empire plunged the university into academic chaos. In the fifties, pinchpenny legislatures used oil money as an excuse to slash UT’s appropriations. Oil had helped make a mockery of the university of the first class. But the mystique survived. After a drive led by one of UT’s most prominent self-critics, Walter Prescott Webb, the original Santa Rita rig was installed on the UT campus.

Before 1959, the interest from PUF (the principal is untouchable) was used primarily for construction. That year UT set aside $1 million to start an “excellence fund.” But the fund, now $34 million, grew more rapidly than the excellence. In the seventies, just when UT got serious about academics, PUF was imperiled because the construction fund for other public colleges ran out of money. They wanted to share in PUF, but if a constitutional amendment is adopted in November, they’ll have to settle for a new construction fund of their own.

Since 1973 PUF has trebled. Even after building a swim center, a basketball arena, and a concert hall, UT has plenty left over. Today much of the oil money goes for high tech, looking to the time when Texas—and UT—will have to make do without oil. Meanwhile, in the bleak emptiness near Andrews and Crane and Big Lake, the wells are still pumping, every six seconds, ten times a minute, and with every rotation PUF moves further past two billion and closer to three.

- More About:

- Energy

- TM Classics

- Austin

- West Texas