Anyone with a basic, Schoolhouse Rock understanding of the electoral college understands that it privileges small states at the expense of larger ones. Wyoming, the least populous state in the country, gets three electoral votes—one vote for every 193,000 residents, according to the 2019 U.S. Census estimates. In Texas, meanwhile, each of the state’s 38 electoral votes represents the will of a whopping 763,000 Texans—the largest number for any state in the union. That tops even the electoral rip-off faced by the 38 million Californians every four years, who get an electoral vote to award for every 718,000 residents. The disparity is even more stark when you consider that there are 34 other states besides Wyoming with a smaller population than the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex alone.

The electoral college is a basic fact of American politics, enshrined in the Constitution, and the system, while inequitable in its current incarnation, has its defenders: without it, they argue, presidential candidates would focus all of their attention on densely populated cities like New York and Los Angeles and Houston, ignoring huge swaths of rural America. Defenders also contend that the electoral college selects candidates capable of winning multiple states.

Opponents of the system, on the other hand, argue that presidential candidates focus disproportionately on a handful of swing states, and that the electoral college helps the two-party system maintain its grip on American politics. The electoral college is fundamentally undemocratic, they contend. As evidence, they cite the two times in the past five presidential elections when a candidate (George W. Bush and Donald Trump, to be precise) won the presidency despite losing the popular vote.

Regardless of how you feel about this system, one thing is clear: the current structure of the electoral college dilutes the votes of Texans in ways that are hard to fully grasp.

Quick refresher: The electoral college grants states a number of electors equivalent to the number of members it sends to Congress. The smallest states—those with two senators and one House member—have three votes in the electoral college. Texas gets 38. That system is great for Wyoming and Vermont, but when you look at it geographically, you can see clearly how it screws over Texans. Here are a few ways to visualize the problem.

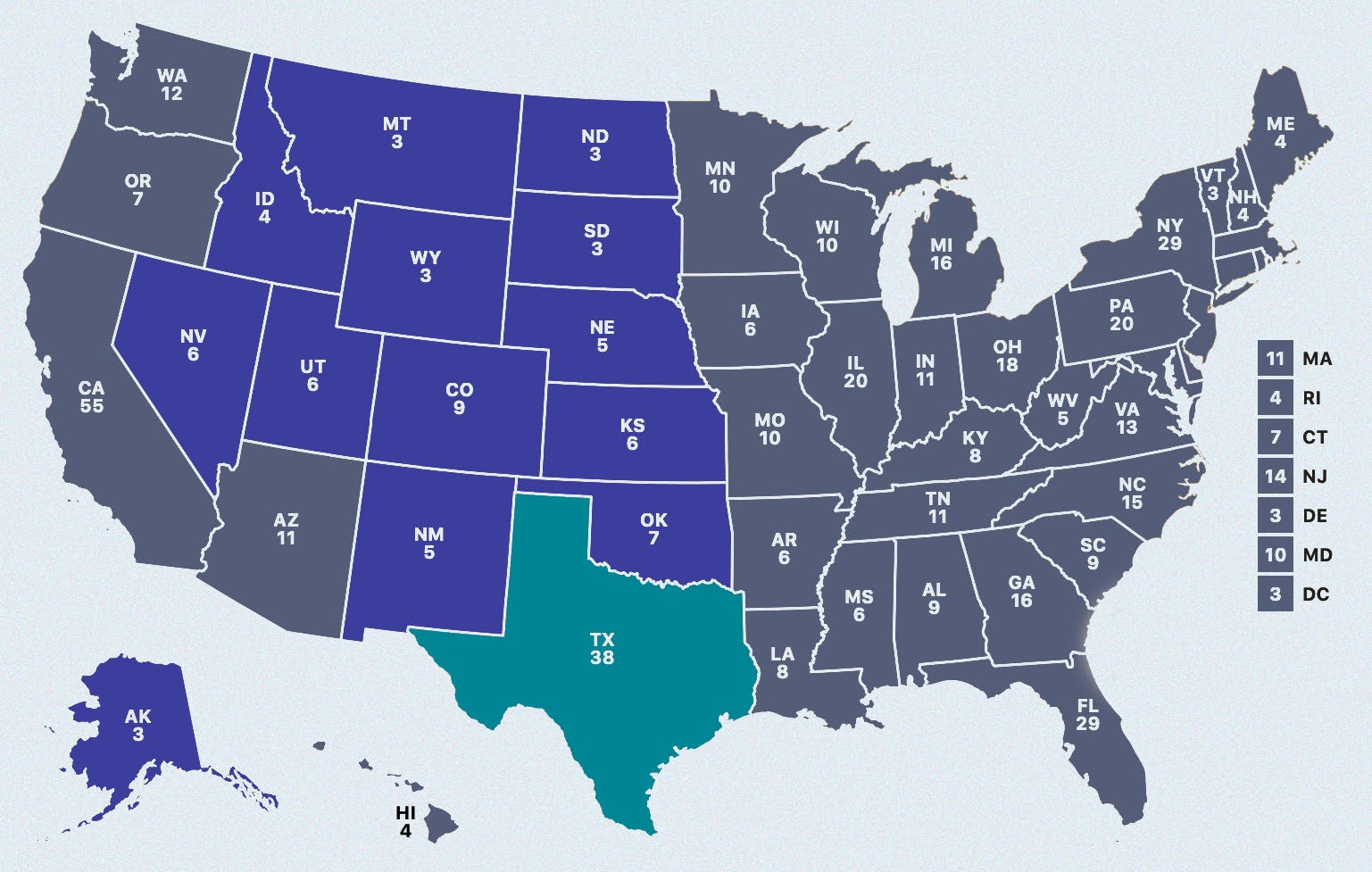

If you look at the Plains and the Mountain West (plus, as a bonus, Alaska!), you can put together a whole lot of states before you get close to the same number as the almost 29 million residents who live within Texas’s borders. Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, both Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, and Alaska add up to about 28.8 million people, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates. Together, they represent 63 electoral votes, compared to Texas’s 38.

If you look at the Plains and the Mountain West (plus, as a bonus, Alaska!), you can put together a whole lot of states before you get close to the same number as the almost 29 million residents who live within Texas’s borders. Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, both Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, and Alaska add up to about 28.8 million people, according to 2019 U.S. Census estimates. Together, they represent 63 electoral votes, compared to Texas’s 38.

There are similar inequities at work even if you pan all the way across the country to the Northeast—where you can slap all seven New England states together, plus throw in New Jersey and Maryland for good measure, and get to a combined population of 29.8 million—fewer than a million more people than you’d find in Texas, yet representing 57 electoral votes to Texas’s 38. As you can see, the imbalance isn’t just about red states versus blue states. Although in the modern era only Republican presidential candidates have made it to the White House without winning the popular vote, John Kerry came close in 2004. He was about 118,000 votes shy of winning Ohio in 2004, and thus the presidency, despite losing the popular vote by more than 3 million. If Texas had its appropriate share of electoral votes, that outcome wouldn’t have been a possibility.

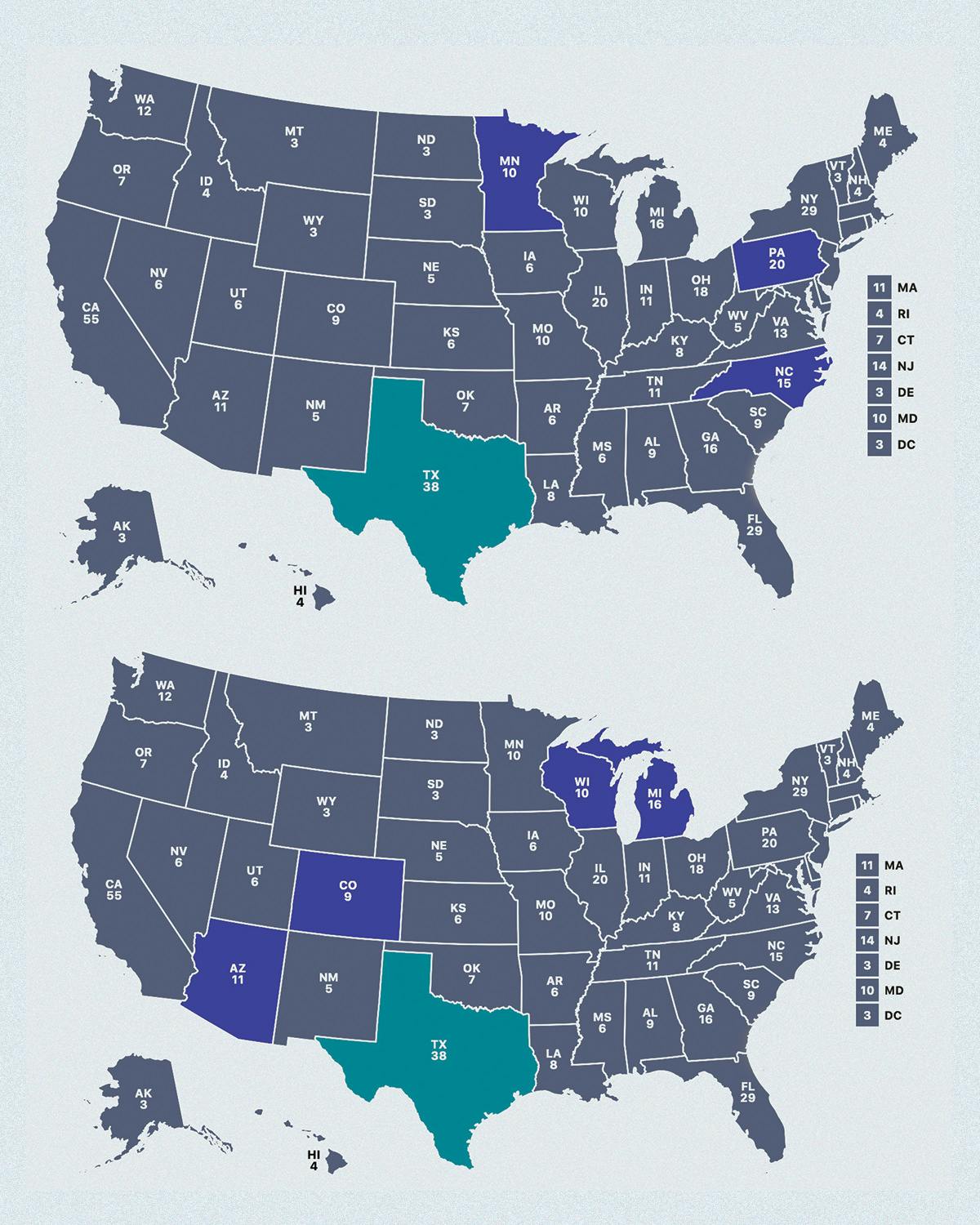

There are similar inequities at work even if you pan all the way across the country to the Northeast—where you can slap all seven New England states together, plus throw in New Jersey and Maryland for good measure, and get to a combined population of 29.8 million—fewer than a million more people than you’d find in Texas, yet representing 57 electoral votes to Texas’s 38. As you can see, the imbalance isn’t just about red states versus blue states. Although in the modern era only Republican presidential candidates have made it to the White House without winning the popular vote, John Kerry came close in 2004. He was about 118,000 votes shy of winning Ohio in 2004, and thus the presidency, despite losing the popular vote by more than 3 million. If Texas had its appropriate share of electoral votes, that outcome wouldn’t have been a possibility. Grouping states that carry more electoral power than Texas by their geographic region is an interesting exercise, but it’s also important to understand how the electoral college gives swing states so much power. In the above maps, you can group either Wisconsin, Michigan, Colorado, and Arizona—with a combined 28.8 million residents—or Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Minnesota (28.9 million) to get 46 or 45 electoral votes, respectively. Not only do these states get a whole lot more attention than Texas in presidential elections, in other words, they also carry more weight than we do, in terms of how much their votes actually count. That’ll be true even if Texas does finally end up earning “swing state” status sometime in the not-too-distant future.

Grouping states that carry more electoral power than Texas by their geographic region is an interesting exercise, but it’s also important to understand how the electoral college gives swing states so much power. In the above maps, you can group either Wisconsin, Michigan, Colorado, and Arizona—with a combined 28.8 million residents—or Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Minnesota (28.9 million) to get 46 or 45 electoral votes, respectively. Not only do these states get a whole lot more attention than Texas in presidential elections, in other words, they also carry more weight than we do, in terms of how much their votes actually count. That’ll be true even if Texas does finally end up earning “swing state” status sometime in the not-too-distant future.

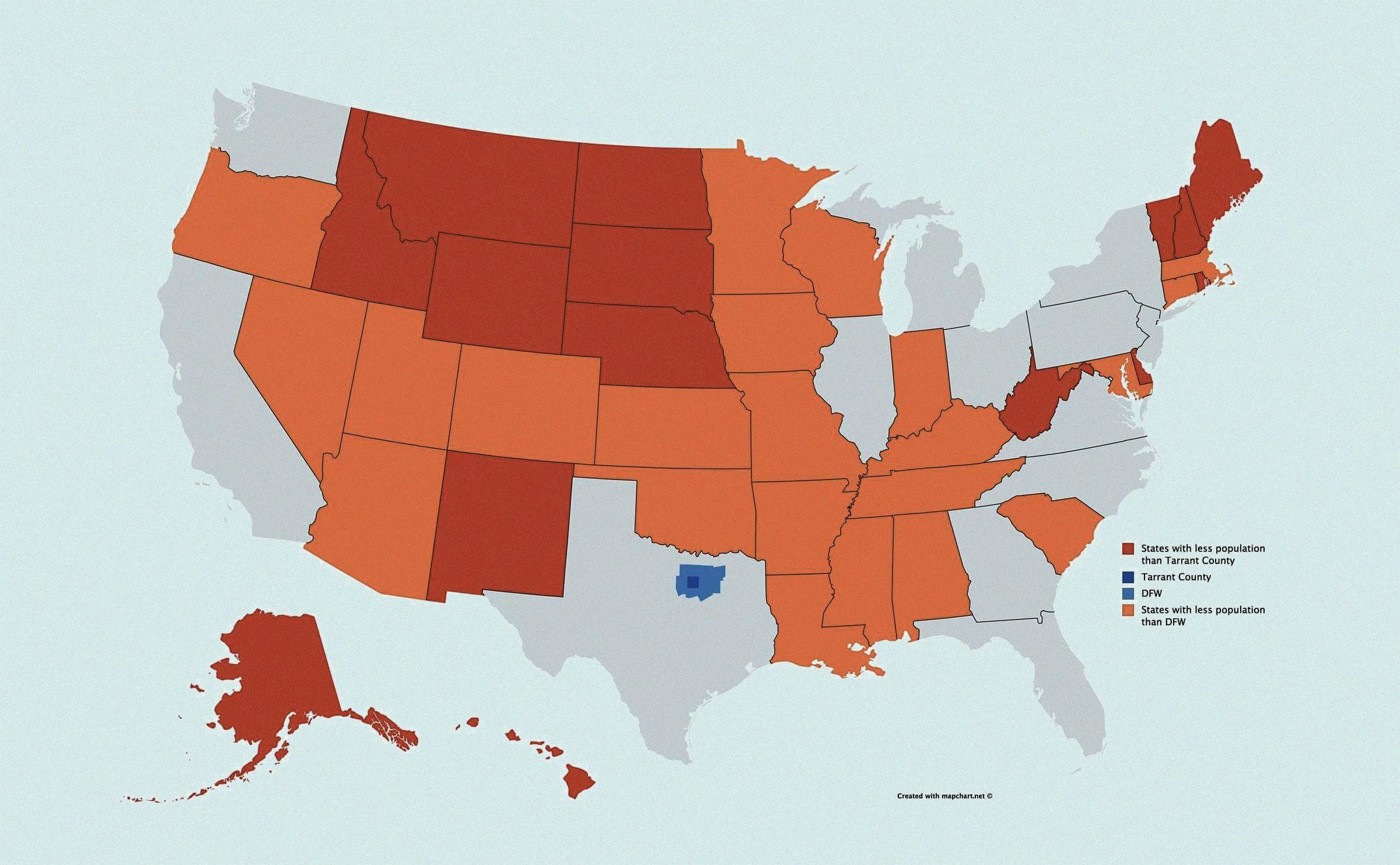

Beyond the state-by-state tallies, though, all of this highlights something unique about Texas. This map by Tarrant County resident Austin James, which was brought to our attention by TCU political science professor Emily Farris, starkly depicts how most states in the nation have smaller populations than the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex by itself. (Fifteen states are smaller than just Tarrant County.) Texas is the only state to have two of the five largest metro areas in the U.S. within its boundaries: If the Houston and Dallas–Fort Worth regions were their own states, they’d be among the largest in the nation. DFW would be number fourteen, ahead of Arizona, while Houston would come in just behind the Grand Canyon State. More importantly, unlike New York or Los Angeles, which both dwarf them in terms of population, both Houston and DFW would be true swing states—if the residents of each region carried the same political relevance as folks in Arizona or Wisconsin, they’d be critical to making or breaking elections.

As it is, those parts of Texas go as ignored as the rest of the state in presidential elections—and rest of the 29 million Texans whose votes carry less political weight than anyone else in the nation get passed over right along with them.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Donald Trump