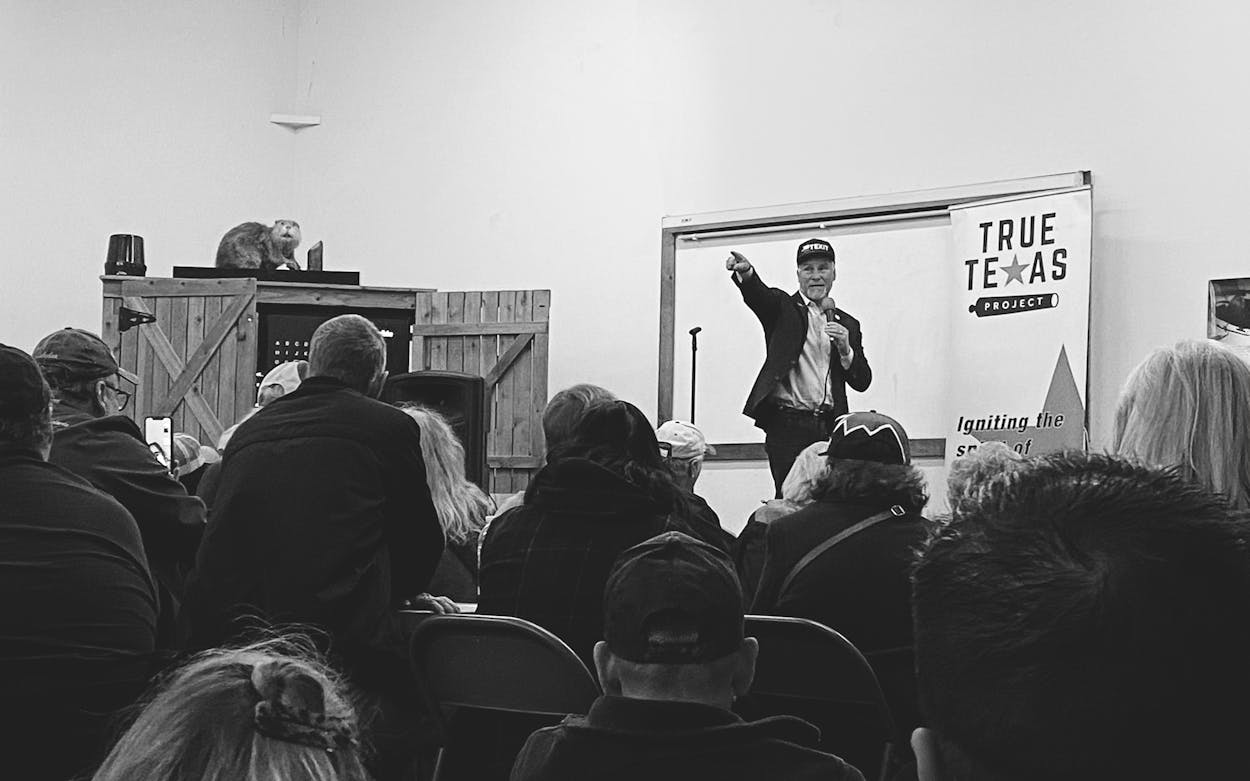

State representative Kyle Biedermann paced at the front of an enclosed room at a paintball park twenty miles north of Fort Worth, a flat-brimmed navy blue ball cap, embroidered with the white-lettered word “TEXIT,” resting atop his head. The hardware store owner from Fredericksburg, one of the last remaining members of the conservative Texas Freedom Caucus, was forcefully spelling out the case for secession. A captive standing-room-only audience of 350 or so, mostly maskless, packed the basketball-half-court-sized room as if they were at a small show at a bar pre-pandemic.

The crowd—almost all white—had come from across Texas to the event, hosted by the tea party group the True Texas Project. In attendance were parents with their children, a host of men in full camo, and women in leopard-print jackets. Suburban Dallas–Fort Worth state lawmakers Bryan Slaton and Jeff Cason had also shown, as had retirees from nearby Roanoke, a traveling anti-abortion advocate, and a government employee from Houston who kept his head down so as not to be identified. “I love America but America’s lost,” Biedermann said with the energy of a football coach, as the crowd intently listened. He paced in front of a taxidermied beaver, which looked shocked, in the corner of the room. “Texas needs to lead, to either fix this, or we’re going to take care of what we need to do.”

Biedermann recently became the first American legislator in nearly a century—and only the second since the Civil War—to file formal legislation calling for secession. The representative, who attended the January 6 rally of Trump supporters at the Capitol but did not storm the building, went public with his plans to propose such a bill on December 8, the deadline for states to certify their election results. Then, six days after President Joe Biden’s inauguration, Biedermann filed his legislation, which calls for a ballot referendum that would ask voters, “Should the legislature of the State of Texas submit a plan for leaving the United States of America and establishing an independent republic?” If a majority choose “yes,” a committee would then write up a logistical plan within a year for how Texas would leave the United States by 2026, though without requiring the state to actually exit.

No other lawmakers—not even Slaton or Cason—have yet coauthored or cosponsored the bill. It has stirred outrage among even old allies of Biedermann. Former fellow member of the Freedom Caucus, Representative Jeff Leach of Plano, tweeted that the legislation was “the most un-American bill I’ve seen in my 4+ terms in the Texas House” and “the very definition of seditious.” “You should be ashamed of yourself for filing it,” he added, addressing Biedermann.

As Texas Monthly has previously observed, contemplation of secession in Texas is a “seasonal discussion.” Texas first joined the Union in 1845, only to secede sixteen years later and join the Confederacy. In recent decades, breaking from the Union has been discussed in concert with national political shifts, typically Democrats winning the White House, and global disruptions, including Britain’s push to leave the European Union. While leaving the U.S. is a fringe idea, it’s one some senior state officials have at least raised as an option. “We’ve got a great Union: There is absolutely no reason to dissolve it,” Governor Rick Perry said just more than a decade ago when asked about leaving the United States after a tea party event in 2009. “But if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people, you know, who knows what may come out of that?”

So when Biedermann filed his legislation, I wondered if there really was renewed interest in leaving the Union, or if it was just a redux of the same fantasy a small minority of Texans perennially make noise about. A lot has changed in the last decade since Perry’s statement—the rise and fall of President Donald Trump, the growing numbers of Americans keen to deny the legitimacy of elections when their candidate loses, and the breaching of the U.S. Capitol by insurrectionists, many of them Texans. In December, Texas Republican party chairman Allen West had also suggested that “law-abiding states should bond together and form a Union of states that will abide by the Constitution” before walking back his statement. Were today’s secessionists serious or, like West, just licking their wounds with similarly brow-beaten conservatives after their man lost the presidency?

No one in the crowd explicitly mentioned the election results to me as a motivating factor for their interest in seceding, but they figured prominently in Biedermann’s argument. “The problem is not just the federal government: It’s almost every single state government we have,” Biedermann told his audience, identifying legislators in Austin, in particular. “How many stood up to the law not being followed in their own states for elections?” (The election results have been audited and repeatedly upheld by judges, many of them appointed by Trump and other Republicans, in the states whose 2020 results were questioned.)

The audience’s disdain was directed more prominently at national politicians, whom they felt had torn the country apart. “I’d like to see America heal,” Ashley Dugger, a registered nurse from Trophy Club, an affluent Dallas suburb, offered as a reason to threaten to leave the Union. She told me after the meeting that she doesn’t actually want to leave the U.S. but wants to send a message—in her words, that “we feel like we’re being canceled”—to the country. Another attendee, Houston engineer and housewife Diane Houk, who traveled 280 miles to the event, told me with a smile that secession was “just a nice divorce with the United States.”

Biedermann, for his part, was clear that he wouldn’t want to actually secede from the Union today, but he wants Texans to put the wheels in motion to make doing so an option. The problem with the federal government, Biedermann told the crowd, is the values of national politicians are not Texas values. Texans, he assured, were tired of feeling that their rights—to free speech and to bear arms, primarily—were being taken away. (The representative failed to identify to the crowd how Texans’ First Amendment rights were being threatened, instead focusing solely on private social media platform’s decisions to ban users, or how the right to bear arms was being infringed upon.) Secession could be used as leverage to negotiate for the kind of country Texas wants from the federal government, he said, urging the crowd to call state legislators—including Speaker Dade Phelan, every member of the Texas Senate, and as many members of the Texas House as they can—and pressure them to cosponsor the bill. “Once we pass this and Texas leads, the whole country, the whole world, is going to say, ‘Oh my goodness, those Texans are at it again,” he said.

Some in the audience, however, did seem to think secession itself was the goal and had grown concerned by Biedermann’s lack of planning. Peter Hernandez, a retired federal prisons hospital administrator from Roanoke, told me he hates big government and likes the idea of leaving the Union, but felt the Fredericksburg representative hadn’t thought his proposal through. What would an independent Texas do about currency and controlling inflation? What about the U.S. Army bases here? Not to mention how much Texas—which received almost $20 billion more from the U.S. government than the $267 billion residents and businesses paid to it in 2019, according to the Rockefeller Institute of Government—would lose out on, without federal support?

After the event, Biedermann told me groups have been hammering out those details for years. He cited the 2018 book Texit and the thinking of the Texas Nationalist Movement, which suggest the state could continue to use the U.S. dollar in the immediate aftermath of secession and likely work out a pact to mutually use the fifteen U.S. military bases. But in front of the crowd, he took a different approach and confidently said he didn’t have time for such logistical questions. “We are not here to play what-if games.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Allen West