This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Mr. Pfeiffer,” the interviewer asks brightly, “do you surf the Internet?”

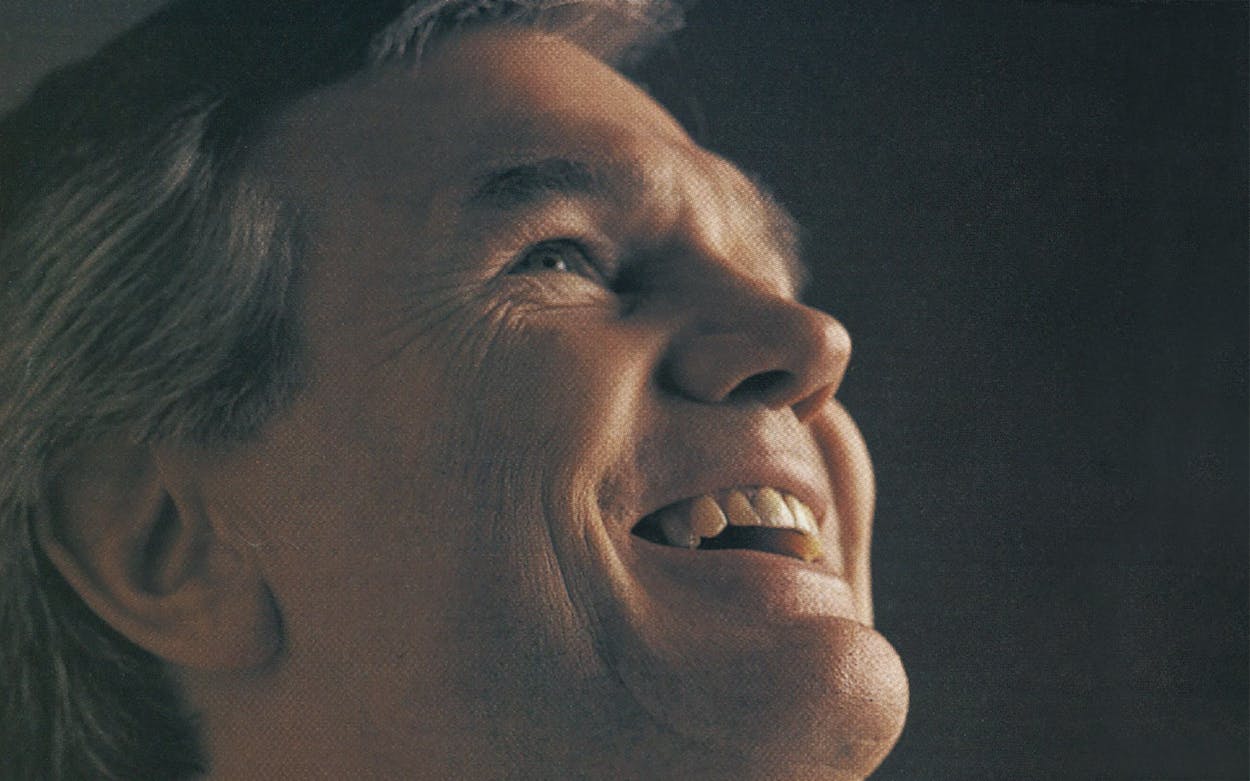

A muscle twitches in the face of Eckhard Pfeiffer, the elegant CEO and president of Houston-based Compaq Computer, the biggest manufacturer of personal computers in the world. “Herr Pfeiffer,” as the 54-year-old German-born executive is sometimes called, looks more like a European count than a computer executive. When women first see him, they tend to describe him as “gorgeous.” He dresses in custom-made suits. His silvery hair is perfectly parted. He speaks in such calm, polished, slightly accented tones that he makes the phrase “market share” sound like a line out of Goethe. In appearance and attitude, Pfeiffer is about as far from an eccentric, Bill Gates–like techno-nerd as one can imagine.

“No, I do not use the Internet,” Pfeiffer says softly.

“Do you ever play computer games?”

Pfeiffer glances at a corporate public relations executive who is sitting nearby and replies, “No.”

“Well, what about tinkering with software?”

Pfeiffer gives his interviewer a stare that could generously be described as chilling. “No.”

“So then,” asks the stumped interviewer, “what is it about computers that excites you?”

Legs neatly crossed, arms folded, Pfeiffer does not so much as blink. But it’s obvious he is not sure what to say. “This,” he says finally, “is a good question.” In fact, for those who follow the often viciously competitive world of computers, one of the great mysteries is how the reserved, phlegmatic Pfeiffer has become the guru of high-tech hardware, masterminding the plan for Compaq to dominate the personal computer market. Since toppling IBM late last year as the best-selling manufacturer of PCs, Compaq has been on a blitzkrieg, churning out computers nonstop in its factories throughout the world. Industry analysts estimate that Compaq will ship between 5.5 million and 6 million PCs this year, with no rival shipping more than 5 million. After achieving $6.46 billion in sales in the first half of 1995, Compaq will probably top $14 billion by the end of the year—stunning growth for a company that had sales of $3.3 billion in 1991, the year Pfeiffer took over.

In the eighties Compaq was the symbol of post-oil Texas. Founded in 1982 by former Texas Instruments engineer Rod Canion and other former TI executives, Compaq seemed no different from any of the 150 other companies around the country manufacturing IBM-compatible clones. But when it produced the world’s first portable IBM-compatible computer—known as “the lovable luggable,” it weighed a then-feathery 28 pounds and cost $2,999—the company took off. Soon it was beating the competition out the door with laptops and notebook computers. By 1991 Compaq was the world’s third-largest PC manufacturer, behind Apple and IBM. But other companies began marketing less-expensive computers that they said worked just as well as Compaq’s. Michael Dell, the founder of Austin-based Dell Computers, ran ads mocking Compaq’s high prices as “lunacy.” As Compaq was about to find out, in the PC business change can take place in nanoseconds, and just like that, the momentum shifted. In late 1991 Compaq posted its first quarterly loss in more than eight years; 1,700 employees were laid off. Canion, the founding CEO and president, calmly said he had plans to restore the company’s earnings, but Compaq’s board wanted a revolution. In a move that stunned Houston, the board fired the legendary Canion and announced that Pfeiffer, the little-known chief operating officer, was Compaq’s new boss.

Born in 1941 in the village of Lauban, Germany (now a part of Poland), Pfeiffer spent the war living with his mother and siblings at his uncle’s in Nuremberg. His father, a banker, had joined the German army and was taken prisoner by the Russians. At the end of the war the family was reunited in Nuremberg, and Pfeiffer eventually graduated from college with a business degree. In 1964 he was offered a job as the office manager of Texas Instruments Deutschland. Within months he was selling TI’s semiconductors in the northern part of West Germany. The confident young salesman bet a case of champagne with a more experienced TI counterpart in southern West Germany that he would outsell him in two years. He did. At 32, Pfeiffer became one of TI’s youngest vice presidents, taking over the European consumer-products division. He was later brought to Dallas to head worldwide marketing for TI. In 1983 he accepted Canion’s offer to set up Compaq’s European operation any way he wished; he moved to Compaq’s Houston headquarters eight years later.

In press reports of his promotion, Pfeiffer was described as “numbers-oriented” and “hard-charging.” Indeed, Pfeiffer worked so relentlessly that one of his associates confided to a reporter, “I don’t have any idea what the guy does for relaxation.” When he played tennis, opponents were overwhelmed by his intense need to win. Bob Stearns, Compaq’s vice president of corporate development, recalls driving with Pfeiffer one day when the two were headed to downtown Houston. “In his Mercedes, he was literally going one hundred miles per hour, even down the exit ramp,” Stearns says. “It was the first time I genuinely thought about death. I got out of the car and said, ‘Jesus, you drive fast.’ He just looked at me and said, ‘Oh, you think so?’ ”

“I do not understand why my desire to win is so surprising to others,” Pfeiffer says. “Perhaps it was my upbringing, having to survive after the war, barely making it for three to four years.” He shrugs, as if already bored with the subject. “Perhaps it was a struggle for survival that may have spawned the instinct to succeed.”

Listening to Pfeiffer describe his impact on Compaq is like listening to Henry Kissinger describe a new world order. He speaks deliberately, in long sentences, making regular references to “volume growth” and “cost-leadership mode”—and he does not tolerate interruptions. “I think a lot of people unfairly miscast Eckhard because he is German,” says Stearns. “Eckhard is not cold. He’s just calm. He’s very analytical. Nothing rattles him. And what’s most amazing about him is that he is an agent of constant change. His message to us has always been, ‘Never stop innovating. Whatever we have done so far is not good enough.’ The man just does not know how to think statically. ”

It took Pfeiffer exactly nine hours to change the corporate culture at Compaq. On the day he was named Canion’s replacement, Pfeiffer ordered a team to start planning a new group of low-priced PCs. He reorganized the company into smaller divisions for better accounting costs and returns; he tied executives’ bonuses to their divisions’ profits. He cut drastically the amount of testing done on the computers before they were shipped. Compaq’s engineers wanted more money for research and development, but Pfeiffer insisted that Compaq’s quality would not be sacrificed.

In June 1992 Compaq caught the industry off-guard with a new line of PCs that sold for about a third of what Compaq had charged for their predecessors. It was a risky move: By slashing prices, Pfeiffer was cutting the company’s profit margin from 43 percent to 27 percent. Critics said there was no way that he could make up that loss with more sales. But Pfeiffer publicly predicted that Compaq would be number one in PC sales by 1996. He was wrong. Compaq was number one by 1994. The new lines of Compaq computers—even the entry-level ProLineas that cost less than $1,000—received favorable reviews from the computer experts. One highly regarded Wall Street analyst called Pfeiffer’s success “one of the great turnarounds in the world. ” While many computer executives have reached the top because of their technological know-how, that’s not the case with Pfeiffer. “He is a business fundamentalist who knows exactly what it takes to succeed in the marketplace—which is something we’ve never had here before,” says Wilson Fargo, Compaq’s senior vice president and chief counsel.

These days, at the weekly meeting of Compaq’s top executives at its tree-lined, college campus–like headquarters in northwest Houston, Pfeiffer acts almost courtly. He is a courteous listener, he refuses to redress anyone in front of others, and he never raises his voice. “No one shouts at each other at Compaq,” says Fargo. “Eckhard finds it pointless. He wants discussions based only in fact.” Still, Compaq under Pfeiffer is far from an easy place to work. One former vice president, who quit in March 1993, said he could no longer take the eighteen-hour days. Once, at a corporate dinner, Pfeiffer asked his executives to write sales projections on a cloth napkin. “All right,” he said, “now make them bigger.”

Pfeiffer, who earned more than $5 million in salary and bonuses in 1994, knows that to stay ruler of all Computerdom he can’t rest on his riches. The PC business, with its billions in sales, is growing phenomenally. According to one estimate, 100 million PCs will be shipped worldwide in 1999, compared with 48 million in 1994. Researchers say more people today want a PC than want a new car. Perhaps Pfeiffer’s greatest strength is, ironically, his ability to sell computers the way GM sells cars. He spends as much time studying market research and customer surveys as he does looking through the technology reports from his engineers. This year’s advertising for Compaq’s new computers cost $100 million—about the same as what it costs to launch a new car.

He also continues to demand change. In March, as part of his strategy to keep squeezing his competitors, he introduced more than a hundred new models of Compaq computers while announcing price cuts of 5 to 23 percent. He also confounded industry experts by revealing more plans to reorganize the entire company. Instead of relying on a huge inventory of computers, Pfeiffer wants Compaq to build its computers to customers’ specifications. And he wants delivery within five days—a system that would mean vast changes at Compaq in everything from product development to manufacturing to information management. In 1993 less than 5 percent of Compaq’s PCs were built to order. Pfeiffer has told his management team that he wants to hit 100 percent by the end of 1996. Although his plan looks like a classic case of fixing something that is not broken, one Compaq insider says, “If a customer who has certain computer needs knows he can come to Compaq and get exactly what he wants in that short time, then Compaq could get a stranglehold on the PC market.”

Ultimately, the secret to understanding Pfeiffer’s love of the computer is understanding his love of competition. To him, computer sales is the best game going in business. He will fight with anyone. Last year he deliberately jeopardized a key relationship with all-powerful Intel, Compaq’s supplier of microchips, when he publicly criticized it for giving better prices to smaller computer manufacturers at Compaq’s expense. Compaq also filed suit against one of its fiercest rivals, Packard Bell, for falsely advertising components in some of its computers. Packard Bell’s president said the charges were “totally without merit and specifically designed to stall Packard Bell’s momentum in the marketplace.” Perhaps as a form of retaliation, Packard Bell executives sold 20 percent of their company to NEC of Japan, giving Packard Bell a huge infusion of capital to make a run at Compaq.

But in typical fashion, Pfeiffer acts utterly unperturbed by the competition. “I take the professional approach,” he says, giving his visitor a look of deadly confidence. “I consider it one of my major strengths. I have had a completely different vision of what is going to be the next phase in this industry. And so far that vision has played out. ”

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Houston