The first official results of the 2020 census are in—and Texas has plenty to brag about. It grew more than any other state over the last decade, according to figures released by the Census Bureau on Monday. There are now 29,145,505 Texans, though as I type this another thousand migrants are surely packing up their belongings in Los Angeles, Lucknow, and Leon. That’s up from 25 million in April 2010, an increase of 15.9 percent, or four million—more than the total population of Oklahoma (which once again makes one wonder why UT has lost two-thirds of its football games against the Sooners over the past two decades). The only other states to exceed Texas’s population boom, in terms of percentage growth, were Utah (growing by 18.4 percent) and Idaho (17.3 percent).

In contrast, the United States grew by only 7.4 percent over the last decade, the slowest growth rate of any decade in the nation’s history, with the sole exception of the Great Depression decade of the 1930s, when the population grew by 7.3 percent.

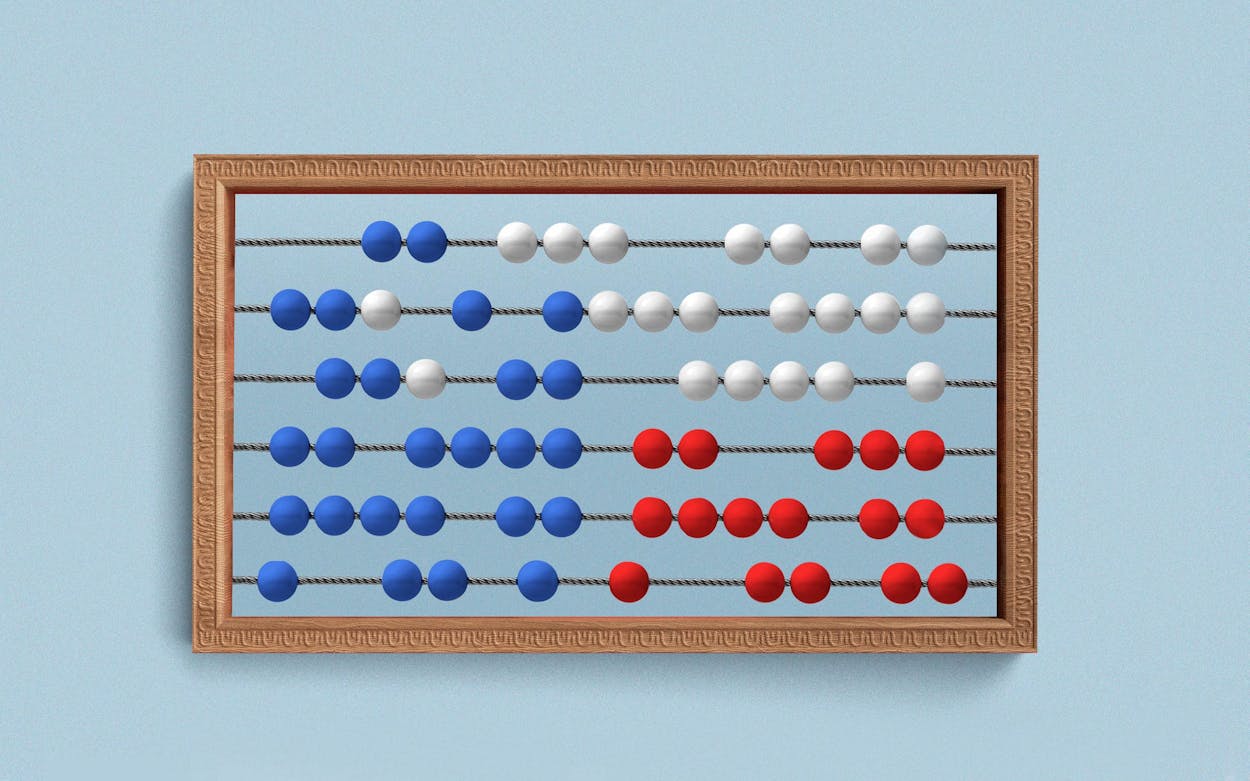

Seven seats in the U.S. House of Representatives were reallocated, with only the Lone Star State adding more than one. (Quick refresher: every ten years, the census results are used to reapportion the 435 seats in the U.S. House among the fifty states. It’s a zero-sum game: fast-growing states tend to add representatives while shrinking states tend to lose them.) Texas will now have a 38-member delegation in Congress, bigger than those of the least-populous seventeen states combined. Add in the two Senate seats, and Texas will have a nice, round forty votes to bring to the Electoral College in the 2024 presidential election.

Sweeter still for some Texas partisans, the gain came partly at the expense of archrival California, the nation’s other mega-state. In the long view of history, if it’s possible to make that call so soon, this week’s biggest news may have been that California has peaked. For the first time in history, the Golden State is losing a congressional seat and an electoral vote (down to 52). Even though California added 2.3 million residents, increasing from 37.2 million to 39.5 million, its growth rate of 6.1 percent was weaker than those of Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and even Nebraska.

Still, there was an undercurrent of letdown for Texas because the gain of two seats fell short of forecasts. “Everybody was expecting Texas to gain three seats, Florida to gain two seats, and Arizona to gain one seat,” said William Frey, a Brookings Institution demographer. Instead, he said, “Florida ended up with one seat instead of two, Texas with two instead of three, and Arizona with nothing instead of one.” Another surprise: New York lost a seat and Minnesota kept one by the tiniest of margins. If New York had counted just 89 more of its residents it would have kept its 27-member delegation intact.

So what happened?

Texas fell about 190,000 residents short of gaining a second seat, according to Michael Li, a redistricting and voting rights expert at the Brennan Center for Justice in New York City, who formerly practiced law in Dallas. Li said there is an object lesson here for Texas. Minnesota has a storied civic culture. It had the highest census response rate of any state and enjoyed the highest voter turnout in 2020. New York invested heavily in a campaign to encourage census participation, without which it might have lost two seats.

Texas, on the other hand, is distinguished by historically low voter turnout (though two-thirds of registered voters cast ballots in 2020, the best turnout since 1992) and low census response rates, and the Legislature in 2019 didn’t budget a dime to encourage census participation. Instead, so-called “complete count” efforts were left to volunteers, nonprofits, and cash-strapped local governments. Some Texas elected officials, Attorney General Ken Paxton in particular, also joined the Trump administration in pushing for a citizenship question on the census that experts said would depress the response rate among immigrants and Latinos. “Texas has a very diverse population, including many people who are hard to count under the best of circumstances,” Li said. “There are lots of immigrants, lots of people for whom English is not their first language, and lots of people who, for various reasons, are a little bit distrustful.”

Even though the Trump administration ultimately failed to add a citizenship question, Texas officials did little to assuage migrants’ fears.

Beyond political power, some $1.5 trillion in federal spending is keyed to census results. The George Washington Institute of Public Policy estimated that even a one percent undercount could cost Texas nearly $300 million a year. “I think there are a lot of people who are afraid of the demographic change that is taking place in Texas,” Li said, “and they would just rather not know.” It also rubs many Republicans raw to be counting people who are not citizens or legal residents for purposes of distributing power.

The next part of the process will be the most contentious. Later this year, state lawmakers will meet in Austin in a special session to draw new districts for themselves as well as congressional members. It’s a highly partisan process that will almost certainly produce a flurry of lawsuits from Democrats, voting rights groups, and racial minorities who will be at the mercy of ruthless GOP mapmakers. The Census Bureau says it will provide states by September 30 with the detailed data, including information on race, ethnicity, and voting age at the local level, needed for redistricting.

Earlier census estimates suggested that Hispanics, African Americans, and Asians account for almost 90 percent of Texas’s population growth. The Republicans who control the legislature must contend with those demographic facts when drawing new state legislative and congressional districts. But they’ve done so successfully in the past. For example, more Latinos live in the Dallas–Fort Worth area than in the state of Colorado, yet there is no Latino member of Congress from North Texas.

In an email on Monday, Democratic strategist Matt Angle, founder and director of the Lone Star Project, a PAC that works to promote Democratic fortunes in Texas, all but pleaded with Republicans to “do the right thing” by preserving congressional districts that give Black and Latino candidates a shot at winning.

All thirteen Texas congressional districts held by Democrats “should be preserved in some form, and then the two new seats certainly should be drawn probably as Latino seats, given the population growth.” That would still likely give Republicans 23 of the 38 seats, or 60 percent, which is more than the vote percentage that any Republican gets in a typical statewide election. “Any map that doesn’t net out 15 seats where minorities have the strongest voice is probably a violation of the Voting Rights Act,” Angle said. “I don’t think [Republicans] will concede to two Democratic seats. I fully expect them to violate the Voting Rights Act.”

In a state in which Republicans hold all the levers of power, and in a nation where Democrats control the U.S. House by just a six-vote margin, and Republican appointees to the Supreme Court have proven ready and willing to weaken the Voting Rights Act, there seems little chance of Republicans conceding anything. As Senator John Cornyn tweeted on Monday: “Texas will gain the most new seats in the U.S. House of Representatives under new Census numbers released Monday, while states in the Northeast and Midwest will lose seven seats, shifting some political clout to Republican strongholds before the 2022 midterms.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy