In high school, Kate Fowler started having terrible nightmares. Her younger sister would be chased by monsters, or assaulted by strange men, or trapped in a burning house. Sometimes Kate saved her sister. Most of the time she couldn’t. At night, Kate was afraid to fall asleep; during the day, she felt anxious and depressed. Kate’s parents, Nancy and Loren, took her to therapists and psychiatrists, who prescribed medication used to treat PTSD. Nothing seemed to work. “We had a whole mental health team around her, but this poor child couldn’t sleep,” Nancy Fowler told me.

Last fall, Kate matriculated at Texas Lutheran University, in Seguin, where she planned to major in biology. She hoped to become a doctor—perhaps an oncologist, like her uncle. After finishing her first semester, she returned home to her parents’ house, in the Houston Heights, for the academic break. On Christmas Eve afternoon, Nancy entered Kate’s room and found her eighteen-year-old daughter sitting on her bed, legs crossed, body slumped forward. She was stiff to the touch. Nancy later learned that Kate had purchased a Percocet on Snapchat, the social media app. Unbeknownst to her, the pill had been laced with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is approximately fifty times more potent than heroin and a hundred times stronger than morphine. Paramedics told her that Kate had probably died within minutes of taking it. “I think she just wanted to be able to sleep in peace,” Nancy said.

In 2021, the most recent year for which complete records are available, more than 100,000 Americans died from drug overdoses, an all-time record. Synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, accounted for 71,000 of those deaths. Drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death for Americans between the ages of 18 and 45. In Texas alone, more than 5,000 people fatally overdosed last year, according to preliminary CDC data.

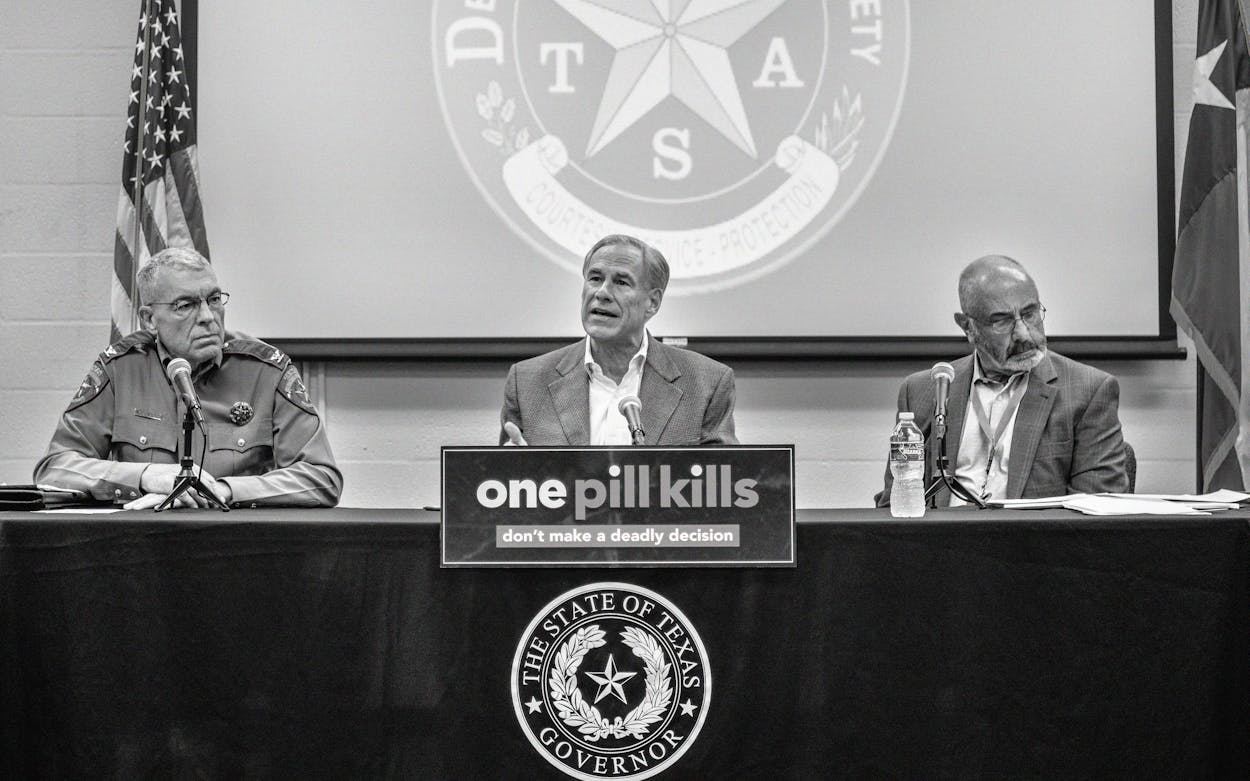

In his February State of the State address, Governor Greg Abbott made addressing the fentanyl crisis an emergency item in this year’s legislative session. Stating that Texas Department of Public Safety officers have seized enough fentanyl to “kill every man, woman, and child in the United States,” Abbott called on lawmakers to classify fentanyl deaths as poisonings, which would allow prosecutors to charge drug dealers with murder. He also advocated increasing the supply of Narcan, an overdose-reversing treatment. (Last month, the Food and Drug Administration approved Narcan for over-the-counter sale.) After years of opposing fentanyl test strips—which are used to determine whether drugs contain the potent opioid, but are currently considered “drug paraphernalia” under Texas law—Abbott announced in December that he now supports legalizing them. “There’s going to be a movement across the state to make sure we do everything that we can to protect people from dying from fentanyl, and I think test strips will be one of those ways,” he said. (In response to an interview request for this story, Abbott’s office referred me to his State of the State address.)

Abbott appears to have become favorable to test strips after meeting with several families that have lost children to fentanyl. One of his guests at the State of the State address was Veronica Kaprosy, whose seventeen-year-old daughter, Danica, died after taking what she believed was Percocet—but which turned out to be a fentanyl pill. Danica had just finished her junior year at Veterans Memorial High School, in San Antonio. She suffered from insomnia and food allergies, which she had been secretly treating with pain medication that she obtained from a friend. On an ordinary morning last July, Veronica looked into her daughter’s room and saw her leaning forward in bed, motionless. “I went to touch her to wake her up, and she was cold and hard,” Veronica told me. “I screamed for my husband, and he ran into the room. He asked me what was wrong, and I said ‘Danica’s gone. Our baby’s gone.’ ”

Veronica later shared her story with her state representative, John Lujan, a Republican from San Antonio. “When I was a youth, they would tell us to stay away from drugs, but people experimented, including me,” Lujan said. “You can’t do that nowadays. Students will take something that they think is innocent, to help them relax or help them study, and then they’re dead.” Lujan, who later introduced Veronica to Abbott, has authored six fentanyl-related bills in the current legislative session, including HB 1018, which legalizes test strips. The companion bill in the Senate, SB 207, is being carried by Democrat Sarah Eckhardt, of Austin, one of the Legislature’s most liberal members. “I wanted to keep the bill bipartisan to show that this is not a political issue,” Lujan said. “We should all be worried, and we should all be working together on solutions.”

Several similar bills have been introduced in both chambers, but none have yet made it out of committee—a worrisome sign to first responders and drug policy experts. Mike Lee, chief deputy in the Harris County Sheriff’s Office, told me that he would like to provide his officers with test strips to go along with the Narcan they carry. “We were probably one of the first large agencies in the country to equip our deputies with Narcan,” he said. “Early on, it was pretty controversial among law enforcement agencies. There was this school of thought that said, no, that’s not our role. That’s encouraging drug abuse. But our philosophy is, look, if someone has a gunshot wound, you do everything you can to save their life. That’s why deputies carry tourniquets. So why would you not try to save the life of someone, just because they made a bad choice?”

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, offers grants to law enforcement agencies to purchase test strips. But Lee can’t apply for the grant so long as the strips are considered drug paraphernalia in Texas. Even if the test strip legalization bill passes, Lee worries that it will already be too late. Other adulterants, such as the animal tranquilizer xylazine, known as “tranq,” have already started showing up in toxicology reports in Harris County. Then there are nitazenes, synthetic opioids developed in the 1950s that can be up to forty times more powerful than fentanyl. Unlike fentanyl, nitazenes have never been approved for medical use, but they have recently started showing up in street drugs in the U.S.

Lujan has also introduced HB 3540, which would create a centralized database to track drug overdoses, and HB 4374, which would require public schools to educate students about the dangers of fentanyl. HB 4173, authored by Republican representative Stephanie Klick, of Fort Worth, would broaden the state’s “Good Samaritan Law” in order to encourage people to report overdoses. First passed in 2021, the law currently provides immunity from prosecution for anyone who reports an overdose—but only if that person has no previous drug convictions and has not reported an overdose in the past eighteen months. Klick’s bill removes those restrictions.

That’s especially important considering the likely passage of SB 645, which increases criminal penalties for fentanyl manufacture and distribution, and would allow prosecutors to charge anyone with murder who knowingly provides a fentanyl pill that results in a fatal overdose—as Abbott requested in his State of the State address. The bill is coauthored by one Republican (Joan Huffman of Houston) and four Democrats (Juan “Chuy” Hinojosa, of McAllen; José Menéndez, of San Antonio; Borris Miles, of Houston; and Royce West, of Dallas). It passed the Senate by a unanimous vote on March 15 and is currently under consideration in the House. “With such a serious charge on the table, it’s going to make people even less likely to call 911,” said Cate Graziani, executive director of the Texas Harm Reduction Alliance, which advocates taking a public health approach to drug addiction. “With the penalty enhancements, people aren’t going to report overdoses, because they’re afraid of the repercussions.”

That’s what happened to Sarah Hall’s son, Ethan. In August 2020, Ethan overdosed on fentanyl while hanging out with a friend in his bedroom, in a quiet subdivision in Montgomery County, north of Houston. His friend didn’t call 911, perhaps fearing that she would be charged with drug possession. Instead, she called a mutual acquaintance of Ethan’s and left a voicemail. It took nearly an hour for the acquaintance, who was babysitting, to get the message. She immediately called 911, but it was too late. Sarah arrived home to find her house surrounded by cop cars and ambulances, and a paramedic eventually told her that her 22-year-old son was dead. “Ethan’s friend chose to stay there with him and do nothing,” Sarah told me.

Katharine Neill Harris, a drug policy scholar at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, told me that stiffening penalties for selling fentanyl would likely prove ineffective. “I’m kind of amazed that we haven’t learned this lesson by now,” she said. “Tough penalties don’t deter drug use, and they also aren’t going to deter drug selling.” As for charging dealers with murder, “very often the person that ends up getting prosecuted is a friend or family member or partner of the person who dies,” she said. “You have these situations where two people know each other very well, and they use together. One of them dies, the other one doesn’t, and the one who doesn’t is prosecuted with murder.”

For this story, I spoke to five mothers who recently lost children to fentanyl. Several seemed ambivalent about charging the person who gave their child the fatal pill with murder. “It just triggers more trauma for me, because then it’s like, oh, she was murdered,” said Ginger Treanor, whose daughter Brooke died in 2021, at the age of 26, after taking fentanyl-laced heroin. “Part of me wants to say, just let it be an accident so I can get on with my healing.” Annie Hernandez’s son Joshua died in 2019 after taking a Xanax pill containing fentanyl. “In the 1980s, during the crack epidemic, they just put all the people that were doing crack in prison, and suddenly we had this prison system of people that really needed mental health,” she said. “So I wouldn’t be behind [increasing penalties] unless you got the big guys.”

Drug policy experts generally agree that a public health approach—investing in harm-reduction strategies, evidence-based rehabilitation, and safe opioid alternatives such as methadone—have proven far more effective at reducing drug fatalities than the law-and-order approach that characterized America’s failed war on drugs. In the two decades since it decriminalized all drugs, Portugal has seen its drug-induced death rate fall to one-fifth of the European Union average and one-fiftieth of the American rate.

Over the same period, the U.S. was suffering through the worst addiction epidemic in its history. The widespread marketing of Oxycontin and other painkillers hooked millions of Americans on synthetic opioids. When the FDA finally clamped down on legal opioid prescriptions, many of these Americans turned to heroin—until drug cartels learned that fentanyl was cheaper to produce, easier to smuggle, and far more potent. “We are in a policy-created overdose crisis,” Graziani said. “The fentanyl overdose crisis was created by punitive laws that limited people’s access to legal opioids. So it’s especially frustrating when the government is doubling down on those same policies.”

Harris, the Rice University drug policy expert, agreed. “The ironic thing about where we are now is that if everyone was still using [prescription] Vicodin and Percocet, we would have far fewer overdoses. Those drugs have risks, but they’re much safer than what we’re seeing now. People knew the standard dosage, and what it was. Now we’re in a completely different situation. We really need to expand access to medically assisted treatment options, like methadone and buprenorphine.”

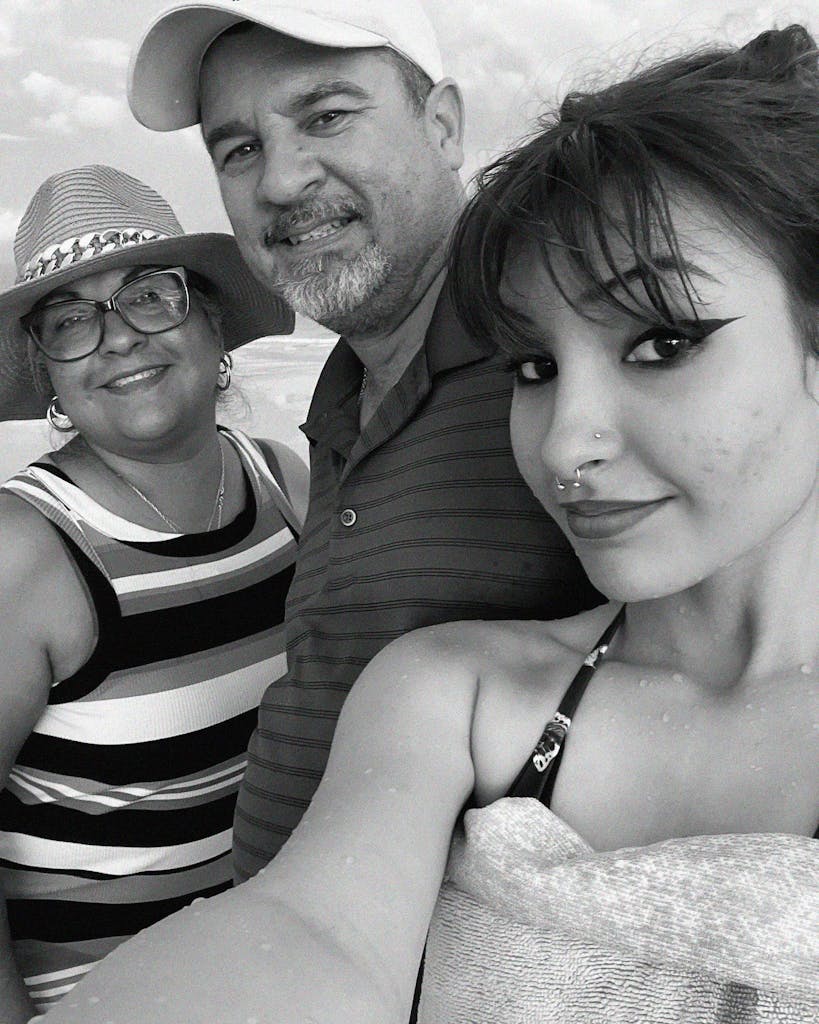

In the months since her daughter Kate died on Christmas Eve, Nancy Fowler has connected with several other families that have lost loved ones to fentanyl. Like many of these families, she wants to share her story as widely as possible, and plans to testify in front of the Legislature in favor of fentanyl test strips. “I’m willing to put myself in uncomfortable positions to save anyone from this hellish pain that I feel every day,” she told me. A Facebook post she made in late January, which included the last family photograph she took with Kate, went viral and led to a series of appearances on local Houston news broadcasts. “I probably have fifteen or twenty messages on my phone from moms who have lost one child, two children, their only child. There are so many deaths, it’s like my phone is heavy. We’re all part of this club that no one wants to be in.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Texas Lege

- Greg Abbott