This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On one of those dank, sweaty, angry evenings that Southern cities seem to incubate in early Spring—April 25, to be exact, 1970—Willie Pierce and two friends were on the streets, looking for action. Tough kids, city-smart. Tom Tirado was parked on a haphazardly lit Houston street, preparing to go home after a late stay in his office. Quite wealthy, elderly, suburban-naive. Willie Pierce shot him twice in the head with a .25 caliber pistol.

Existential murder it ought to be called, violence sprung full-blown from a twisted age, an accidental intersection of weapons and weather, culprits and cultures. They are a homicide detective’s nightmare, lacking all of those rational reference points, motives, modus operandi, telltale signs of premeditated action and post-facto fear through which TV cops can induct and deduct their way to fit resolution of TV murders. Lt. Jim Gunn, who has to work for the Houston Police Department instead of NBC, was (as they say on the tube) baffled.

A week later, May 2nd—8:45 p.m., according to police files—Gunn got a call from Dudley Bell, a Houston private investigator. Bell said he was going to enter the case if Gunn didn’t mind, Gunn responded that that was fine: “We need all the help we can get.” Bell checked periodically with Gunn after that, apprising him only of a lack of progress. Then, on May 20th, Bell called Gunn and asked to meet him at a small apartment project where Bell introduced Gunn to Norris Victoria, one of the three youths. Then, according to Gunn’s police report, “acting on information provided by Mr. Bell I sent detectives to the home of Norman Gladney and he was requested to come to the Homicide Division.” Gladney and Victoria both confessed to what had been their roles in a fumbled stick-up, fingered Willie Pierce as the man who pulled the trigger.

“Based on the information provided by Norris Victoria,” the file continues, “a warrant for murder was sworn out against Willie Pierce. I requested Detectives Adams and Gibson to attempt to arrest him at a location provided me by Mr. Dudley Bell. He was at that location and was arrested.”

“Hell, I’ve never been anything but a private investigator. I started out in high school. I’d read all those books, y’know, private eye novels and stuff, and I got started in just by going ‘shopping.’ That’s where you go around checking on sales clerks to make sure they’re not cheatin’ on the stores, ringin’ stuff up wrong and all.

“Then while I was going to school [University of Houston, ’58, business administration] I was doin’ a lot of part-time work for other investigators. After I graduated I just went into it full-time on my own and been doin’ it ever since.”

The office appears on the surface to resemble that of any other white collar professional: phoney walnut paneling, color-coordinated rugs and wallpaper, a little sliding glass window separating the receptionist from the waiting room. The waiting room offers a stack of somewhat offbeat magazines—Security World, Popular Electronics, Bulletin of the International Association of Private Investigators—and the usual assortment of personal momentoes: a note from Diana Hobby expressing thanks for help in Bill’s campaign; an autographed picture (“to the super-sleuth”) from his uncle, Joe Tonahill, together with Melvin Belli and their client, Jack Ruby; a letter from Congressman Bob Casey regarding Bell’s investigation of the Apollo 204 fire for Gus Grissom’s widow; a few examples of Dudley Bell’s private collection of elephants, numbering some 200 in all, stuffed, molded, carved, etched, painted.

Inside, in his private office, Bell pulls back the curtain to show visitors the dangling microphone cord. See, he laughs, we took the mike out so you’ve got nothing to worry about. Whew, sighs the visitor, relaxing, prepared to be less guarded in conversation. No one points out the tiny hole in the acoustically-tiled ceiling, through which protrudes a miniature microphone. Bell does not open his desk drawer to reveal the tape recorders, running almost always, some connected to the seven different telephones in his offices. There is no mention of the microphone just beyond the door in the elevator landing; “You’d be surprised what people will say right after they leave your office and think you can’t hear them. And then there’s people who come up here who want to talk to me outside of my office, like trying to bribe me or something, and this way I can record those conversations.” When you’re not looking, he or an assistant snaps your picture with a subminiature camera.

“Hell, we’ve got people coming in here all the time masquerading as clients. They could be working for other investigators, trying to find out how we work, or federal agents trying to catch us doing something illegal.” He points down the street, two blocks away, where the telephone repairman sits high up on a pole, playing with wires and circuits in a switchbox. “Now that switchbox down there handles all the telephones on this block. That fella is probably workin’ for the DPS or some state law enforcement agency and is tappin’ my phone. Happens all the time. Federal agents don’t ever have to screw with that sort of thing, they just go down to the central exchange and tap in there. Ninety percent of the security people for the phone company used to be FBI agents, and you tell me they ain’t helpin’ their old friends out when they want to tap somethin’.”

Room 6623 of Houston’s Federal Building is labeled on elevator maps as the Communications Room and is surrounded by unmapped corridors belonging to the FBI, IRS, U.S. Marshalls, various arms of the Federal Government’s effort to find out what’s going down in America. It is one of the largest rooms in the building and houses a complex wall of electronic equipment, machines that jump to life when certain Houston phones are picked up, stamp the time of the call on a little card, kick back to trace the number of the other party, recording it all. “They’ll probably deny it if you print it, but I’ve got a friend who used to work for Motorola who installed all that stuff, and he’ll tell you.”

Bell’s prime assistant, his answer to Dr. Watson, goes by the name of Casey. He is boyish-looking, thin-boned with whispy blonde hair, has the appearance of an anemic Michael Caine. He also has a master’s degree in criminology, a black belt in karate, facility with four languages and a pilot’s license, was a weapons specialist in Army Special Forces and a special agent for the Organized Crime Division of the IRS. [Brief note on what that last means: IRS special agents float somewhere in the upper reaches of the law enforcement universe, possessed of a conviction record roughly twice that of their FBI counterparts. They are the inheritors of the underworld wisdom, attributed to Meyer Lansky: “If the cops get after you, you can generally forget about it; if the FBI gets on you, a good lawyer can usually take care of it; but if the IRS is onto you, you’d better be careful.”] Casey’s addendum on Federal wiretaps: “Nixon came out last year, y’remember, and said there were only 50 wiretaps in the country? Hell, when I was an agent in Miami, we had 50 on one block.”

The Federal Government maintains a telephone number that their agents can always call to see if the phone they are speaking on is tapped; if the number dialed results in a busy signal, then the phone is bugged. The number is changed monthly—more often if necessary—and when an old number is called, a recording tells the caller that the number dialed has never been operative. The number for March was (202) 530-9944.

Dudley Bell is the best-known, probably the best, private eye in Texas, among the best in the country. He handles cases ranging all the way from missing persons (“not too many, they usually aren’t worth the trouble”) to industrial espionage and murder. He tails young executives for companies pondering promotions, curious about what prospective corporate officers do in their free hours, and follows spouses for husbands and wives pondering divorces, wondering the same thing. He has worked cases all over the world but, he figures, about three-quarters of all he has taken have been in Houston.

He looks rather like one expects private eyes to look: well over 6 feet and big, with forbidding dark eyebrows and a protruding, mean-looking lower lip. Some of his friends call him “Mannix” but his ambling, loosely-jointed walk and up-swept Bob Hope-style nose destroy attempts to fit him into the tough, TV-cast mould of the detective. His father was a golf pro at a Houston country club and he grew up adept at the sports of the country club middle-class: golf and swimming. He still holds the city 9th grade records for the 100 and 200 meter freestyle, won a gold medal in the 1952 Junior Olympics. He spent most of his Army hitch in the 101st Airborne Division as Gen. Westmoreland’s golf partner.

“I guess we’re about the biggest investigative and security outfit in the state,” he says, sinking back into the office chair, propping alligator shoes on the desk. “We’ve got about $25,000 just in debugging equipment. We get a lot of that, companies hiring us to check out their offices to make sure other companies aren’t spying on ’em.” The suit is Standard Business Look, $200 Sakowitz double-knit, but the shirt is custom-tailored and monogrammed. The workmanship is not apparent in fancy patterns, or noticeably good fit but, rather, is revealed—or unrevealed, actually—by the hidden interior pockets and invisible buttonholes, receptacles for wires, microphones, miniature cameras, an electric haberdashery that would tax the combined wisdom of Edison and Brooks Bros.

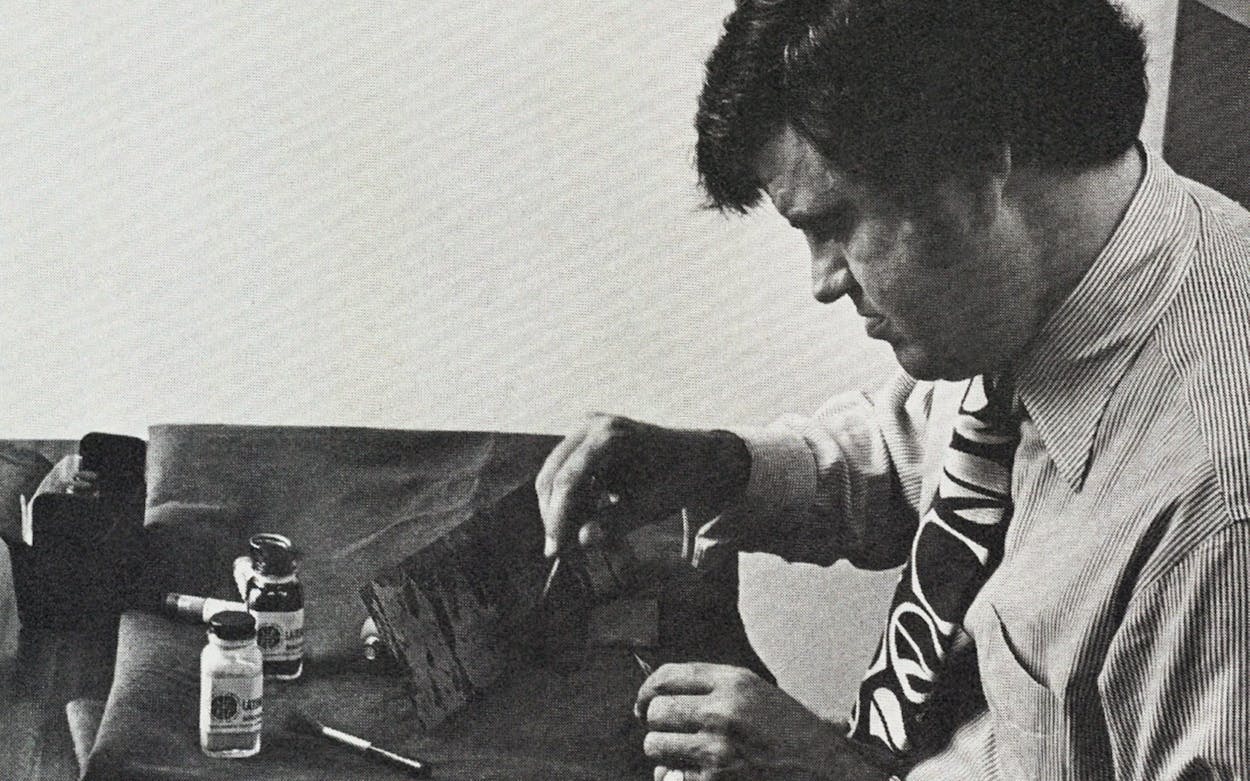

Like most other modern enterprises, private detectives have bent technology to the furtherance of their craft, and most have taken to studying electronics with the energy once invested in, say, marksmanship; Bell, for example, is an accomplished amateur electrician who designs much of his own equipment.

A brief digression into the Architecture of Eavesdropping.

The Federal Building in downtown Houston is without question one of the most aesthetically scandalous monsters ever thrust upon an American city. Gaunt, rectilinear and prisonlike, irredeemably ugly, it has drawn the wrath of architects and critics ever since it was built. Inside, though, off in the southeast corner of the ninth floor, is its one saving grace. The Federal Grand Jury Room, staging area for investigation and inquisition, hotbed of private interest and public curiosity, sits a narrow lonely corridor away from, of all possible neighbors, the Press Room.

It is possible to secret a miniature transmitter in the Grand Jury Room and then sit twenty-odd feet away in the Press Room, miniature receiver and tape recorder hidden in a desk drawer, an earphone wire run up a shirtsleeve, and innocently bang away on a typewriter while recording all that privileged testimony. It is of course marginally risky: The transmitter can be detected when the U.S. Marshalls make their usual sweeps to debug the Grand Jury Room, but they never sweep when the jury is in session.

Most of those millions of folks who hunker down at the nearest TV set to catch Mission: Impossible reruns every week are probably happily unaware of the fact that their TV heroes would get five years in the slammer if they got caught using all those gadgets of theirs in real life. Private detectives think about that a lot.

Back in 1968 Congress passed a bulky, typically ambiguous thing called Public Law 90-351, elsewise known as the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. “Ominous” it was called by civil liberties groups who bemoaned all those little privacies that appeared about to slip down the drain. They were pooh-poohed as alarmists and, amidst deafening crescendos of law’n’-ordah rhetoric, Congress passed the bill in a blaze of unanimity. After all, what politician in his right mind would be caught voting against Safe Streets in an election year?

Buried somewhere in the middle of the 42 pages of single-spaced, tiny agate type (and bearing, one must assume, at least some minimal kinship to Safe Streets) of P.L. 90-351 are all of the Federal laws governing wiretaps, bugs, electronic surveillance and all the gadgetry of nosiness that Mission: Impossible fans get off to. If you read it real close, it says it’s illegal. Sort of. Well, maybe, it just depends. . . . That’s the way Federal laws are written, so that you can’t really be sure just what it is they do say.

At any rate, and even if you choose to believe the ridiculously low numbers of legal wiretaps the Justice Department tell us about, buggery is big business. The key test of legality, it appears, is whether any of the people being bugged, tapped, etc., know about it. If there are 20 people at a conference table and one of them knows about the transmitter in the flower pot, then it’s OK. If you want to tap your own telephone, or all the ones in your offices (a la Dudley Bell), that’s fine, too. It’s a lot more complicated than that, and like any good law it’s shot through with loop-holes, but that’s about what it boils down to.

What this all means is that it’s incredibly easy to get all those trickly little doodads you see ’em using on TV all the time. There are places all over the country that will send you, C.O.D. for the most part, anything you can pay for, no questions asked. Miles Laboratories in New York has a whole catalog just of “telephone monitoring devices.” Sanyu Electronics over in Tokyo gaudily asks “Do You Want To Be Mr. CIA Man?” in their advertisements and take mail orders for a vast array of snooping equipment. You can buy infra-red attachments to cameras and binoculars, some of them modeled after U.S. Army equipment, snorkel microphones, microphones, souped-up pre-amplified miniature microphones, listening devices of mind-fogging sophistication. You can, you really can. Anybody can!

The assumption that allows them to be so easily peddled, of course, is that you’re going to use them legally. Heh, heh, Catch 22. ‘Course who’s to know, right? People in the mail order business are a pretty trusting lot.

“It’d be perfectly all right if they caught you with this thing, see?” says Bell, “but they’d probably bust me with it.” The “it” that he’s holding up is a pen. What’s this? No, it’s not really a pen, . . . it’s . . . well, waddaya know, it’s a radio receiver. And a special one at that, powerfully boosted and set to pick up signals in the 125-140 megacycle range. That’s the bandwidth reserved for airplanes.

“You can sit out at the airport and listen to everything they say up there.” Groovy, right? There are, in addition, a wealth of other audio possibilities. One can set the tiniest of transmitters at about 130 megacycles, plant it in somebody’s car or office and sit around peaceably with your pen in your ear listening to what they have to say. Unless you’re in the middle of an airport, there’s not a chance of anything interfering with your signal. But that would be an illegal use of the device. Which doesn’t mean you can’t have it, they’re just gonna assume that you dig listening to airplanes. But if Dudley Bell has one, they’re going to figure he’s doing something nasty with it and they’ll probably arrest him.

One of the occupational hazards of being a private eye is that they skip pretty quickly along that fuzzy, faded line between what’s legal and what gets you two-to-ten. Dudley Bell’s been arrested more than a couple of times, generally on marginal kinds of things (e.g., concealed weapon), chance missteps while dancing on that line. He’s never been convicted of anything. As one Courthouse hanger-on charitably put it: “Well, sometimes doctors or lawyers will break the law to help out a client or a patient—hell, even the police break the law sometimes to solve a case—and I guess Dudley probably does the same thing once in a while.”

Bell, needless to say, staunchly protests any implication that he is not morally pure and legally chaste. He does, though, admit that while business overall is up, his various “problems” have cost him a couple of clients, mostly large insurance companies that worry over corporate images and such. “Hell, one of the biggest cases I ever worked was an insurance case—saved Fireman’s Fund a quarter million dollars on a fraudulent claim—and now they won’t even talk to me. Now, I don’t think that’s fair. It just doesn’t make any sense for me to have done any of those things they say I did. Why should I jeopardize my license and a business I’ve spent my life building up by using illegal equipment?” A week after his last “problem,” he was elected vice-president of the Texas Association of Licensed Investigators and named to their ethics committee.

Most private investigators have better sense than to muck around with murder cases, preferring to leave that to the police. TV detectives are the only ones that do public service jobs. Every now-and-then, though, Dudley Bell will perceive a situation where certain factors favor his involvement. Money usually plays a big role here, like the $5,000 reward posted by Tom Tirado’s son. Other incentives take the form of big retainers preferred by insurance companies or vengeful relatives anxious to turn up information that the police for one reason or another have failed to nose out.

Cases like that turn up more frequently than one might think. Houston’s police having demonstrated a remarkable aversion to solving big society killings. Usually if some VIP gets himself knocked off there’s a pretty solid chance of there being another VIP at the other end, and things start getting complicated about that point. Like all big-city agencies, Houston’s police force is highly politicized, and over-zealous pursuit of the rich and powerful is not considered good form by ambitious patrolmen. Far easier to treat River Oaks killings as a kind of aristocratic guerilla fighting, Houston’s answer to The Wars of the Roses.

This hands-off approach naturally creates a profitable vacuum into which Dudley Bell has no qualms about injecting himself. Almost without fail, all of Houston’s headline-grabbing big-name killings end up in his office attended by the promise of fate fees. He is currently working a case that would invariable head up anyone’s list of 1972’s Top Ten Mystery Deaths.

Just as one of Houston’s typically colorless dawns was about to belly up on America’s 196th Birthday, Mrs. Faye Bell Hurley found herself leaving her husband’s eighth floor Memorial Drive apartment. She departed via the balcony. Her husband allowed as how it was too bad but, well, we did everything we could, y’know, tried to catch her an’ all. . . .

Although she was some 40 years younger than her husband, Faye Bell had not been what you might normally call a child bride. As Houston’s daily press cheerfully pointed out, Mrs. Hurley owned a pretty colorful reputation and a police record for lewd dancing and narcotics possession. Her husband, on the other hand, J. Collier Hurley, is a wealthy oilman, a famous River Oaks antique collector, and what’s generally known around town as an Important Dude. Leaping to their duty, Houston’s finest investigated for about half an hour and shut the case. It never occurred to anyone in the Homicide Division to either 1) visit the scene, or 2) take a statement from Mr. Hurley. Too bad, too bad, shameful thing . . . They pronounced it suicide. A bunch of strip-tease dancers held a benefit to pay Faye Bell’s funeral expenses.

There are, as you might guess, some folks around Houston who are a little skeptical about that suicide ruling. One of those is Mrs. Louise Carey, Faye Bell’s mom, who has quietly filed suit against J. Collier, charging that he assaulted Faye Bell “willfully, maliciously and with force and violence” caused her to fall off the balcony. She is suing for a fat lot of money and has Dudley Bell working the case.

(Parenthetical relapse: While it may seem incongruous that civil actions should be filed in cases where no criminal charges have been brought, don’t worry over it. Lawyers like to play those games.)

It is not only murder that finds Dudley Bell skulking around in Houston’s prestige neighborhoods. Wealthy husbands and wealthy wives have the same propensities for dalliance as do their less fortunate counterparts, but they possess as well the resources (read: cash) to invest their jealousy with awesome powers of retribution. Dudley has, indeed, found jealousy to be an amazingly profitable emotion.

The strawberry blonde hair betrays country antecedents and the long, finely wrought legs still retain the muscle tone of seven years desultory ballet lessons back in Lufkin. Katherine is 25, a fashion model who looks like a small-busted Ann-Margaret, high school cheerleader come to the city, bringing with her a bluesy rural looseness and a casual approach to personal relations that tends strongly in the direction of nymphomania, a penchant her husband finds, well, disconcerting. He wants a divorce, but he wants child custody and an easy settlement with it, and he figures Dudley Bell can help get them.

Thursday night, not late. Katherine is in her weekly group therapy session, six floors up in a blacked out office building on Buffalo Speedway. Through the 12X binoculars you can see her from half a mile off, therapeutically rapping away in confident security. Casey is a mile to the north in an MG, connected to Dudley by two-way walkie-talkie, prepared to follow her if she leaves in that direction; Dudley is facing south; those are her only options.

Dudley is in a rented car, the only kind he will drive; he used to have a white El Dorado with police antennae until it proved too noticeable in one case. During the day he often uses motorcycles—”best damn things for surveillance you ever saw”—carrying a few spare shirts and helmets: a quick stop, new shirt and helmet, and you’ve got a whole new person on your tail.

Whenever warranted he uses airplanes: “You can loop around all day drinking beer and follow someone all over the state of Texas and they’ll never know it.” At night you press fluorescent tape into the rain gutters of the followee’s car and circle them like an airborn bloodhound, dropping below the FAA’s 1,000 foot minimum altitude to catch quick turns down wooded side streets.

She’s late coming out, and the cars have been sitting three hours now. Dudley has given no signs of impatience, sipping Dr. Pepper and chain smoking Marlboro’s, peering through the glasses toward the parking lot and the office. “You hafta get used to sittin’ still for a long time when you’re on a stakeout. I had to sit in a damn car for 59 hours one time, taking No Doz to stay awake and pissin’ in bottles. Damn car was fulla empty cans and sandwich wrappers. If you just get outta the car for five minutes to go to the john, you might lose your subject.” Wait some more. Turn on the radio a little bit, drum fingers on dash board. Another smoke, one more Dr. Pepper . . . . tedium. Peter Gunn never had to put up with this. Watch the passing cars. Look up twice a minute to search through the binoculars for the green Camaro in the parking lot . . . . “I’ve sat like this in supermarket parking lots, y’know, and you’d be surprised at the things you’ll see. You can spend three hours at night in any shopping center parking lot in this town and see ten couples drive up separately and leave together.”

“Here she comes,” screeches through the walkie-talkie. From the hedge-bounded church parking lot down the street Casey can see the door. “Subject is getting into car . . . can’t see the license plates from here but it looks like hers . . . nobody with her . . . looks like subject turning this way . . . coming this way, I’ve got her . . . .”

“Eight-six-seven, this is four-five-six, keep on her, we’ll be along in a minute.” The rented Cadillac rockets out of the parking lot, wheeling crazily across three lanes of traffic to make the illegal U-turn, boredom left behind with the empty cans of Dr. Pepper.

“Entering the Southwest Freeway, going west . . .” The Cadillac flashes past red lights like so many telephone poles, clipping eighty, hitting the freeway at ninety, weaving now across five lanes of cars, back and across, looking for openings, hundred and ten, “Exit at Chimney Rock . . . .” She drives like a country girl on Saturday night, hauling ass, no turn signals. “Turning south on Chimney Rock . . . .”

“Eight-six-seven, hit your taillights.” Two tiny red dots on a small car a mile ahead flash off-on, off-on, “Have you in sight, pull off, we’ll take it now . . . .” Casey and Dudley trade off, trading later again and once again, following the green Camaro deep into the dark sterile suburbs that sprawl endlessly to the south and west of Houston. If she stops for a red light her nearest tail pulls over, two hundred yards back, turns off his lights and into a side street, waiting for her to move again. If she makes a light and it flips to red, no matter, truck on through, eighty miles an hour down parallel side streets.

She ends up at an apartment. More waiting, addresses and license plate numbers to check, names to learn. It will go on like this for a week or more, waiting for a pattern to develop, a Schedule of Adultery. Casey will follow her on other nights, together with other part-time assistants, policemen moonlighting for extra cash. Easy job. Dudley is on it tonight because it’s the first day on Katherine’s case and he wants to get a feel for it. It’s the first night of what will become total surveillance, the end of philandering freedom.

By Wednesday of the next week they have a pattern of sorts: Hot Blood. The night before, Katherine had gone to another apartment, gotten stoned and made it with two men simultaneously while Casey, who was getting $30 an hour to observe all this cuckholding, was cranking on a camera from outside a window. The stage was set for Phase Two, the adoption of one lawyer’s First Maxim: “When you’ve got a big divorce case, hire a gigolo.”

(Another digression, this time into the male chauvinism of police terminology: In the public mind, the word “gigolo” conjures up notions of suave Italians squiring lonely and elderly female tourists around the Via Veneto, as much a Mediterranean public service as a crafty way to earn a living. By contrast, the designation “whore” is a sharply pejorative one, carrying images of musty back rooms and dark alley perversions. In reality, they are but the male and female versions of the same general animal, offering the same services in the same manner, the only difference being that the male is a somewhat scarcer breed and commands a vastly higher price. Dudley employs both.)

Robert is a gigolo. He combines all of those assets that women find attractive—tall, dark and handsome, quick-minded, cool-headed and a good lover, a slight touch of lustful nastiness—into a powerful woman-killing package, a heady inducement to adultery for even the most faithful of wives. He works as a bartender, lives well, and is a friend of Dudley’s; he free-lances as a gigolo more by inclination than profession, an easy way of picking up some spare change; his attentions to Katherine will earn him $2,000.

On Thursday Robert wanders into the office where Katherine is working. He’s lost, he says, wants to use the phone. Sure, she answers, glands firing already. He calls, party isn’t there, will call back in 20 minutes, so he waits. They chat. Twenty minutes later the call comes, he leaves. With a date for the weekend. Gigolos earn their wages.

The next day, Katherine’s husband is in Dudley’s office to hear the tape from a phone conversation between his wife and Robert. A stubby, owlish little man who patently had no business marrying so high-powered a wench in the first place, he is a thirtyish, wealthy investment broker who emits the high-pitched karmic whine of a man whose nerves are riding the jangling edge of breakdown. He talks tough, macho, about his wife, how he hates her anyway and has wanted rid of her for a long time, all the while eating downers and nervously lighting two cigarettes at the same time; one can hear the contradictions colliding in his head, sense the ulcer germinating in his belly. He shakes hands with Robert, wanly telling him that he hopes he’ll enjoy it. He manages a dirty joke and swallows a smile. Robert, still earning his money, says it’s a dirty business and he isn’t looking forward to it. In a supreme test of masochism, husband listens to wife describing to another man the pleasure she intends for him—”I’m gonna ride you, dragon-slayer, you’re gonna be King”—and the husband laughs. Then he swallows another Valium and wanders aimlessly out.

Next afternoon, frantically. Katherine has broken another date and wants to go out tonight. Now, honey. Rush, “Go out and rent a car for this stupid tool, he can’t pick up a classy chick in that wreck of his . . . get him a Riviera . . .” Off to Motorola for some gear, find the cameras, rent a video recorder. Oh, Jesus, and film, get some film. Out to Robert’s to rig up the house. Get the room-mate out of the way. Okay, where’s the bedroom? where’s that other microphone?

Robert leaves at eight to go pick up Katherine; he’ll take her to dinner, then they’ll go boogeyin’, come back to the house about midnight to smoke some dope and Get It On. Performance. There are two bathrooms adjoining the bedroom and one has been blocked off, the medicine cabinet removed and a hole cut in the wall. On the other side, in the bedroom, a poster has been placed over the hole and camouflaged (had time allowed, it would have been one-way glass); the bed has been turned to the most photogenic angles, infra-red bulbs installed, microphones hidden and wires laid under the rug. In the bathroom, craning through the slot in the wall, is a tripod for the Sony TV camera (closed-circuit video) and the 8mm. movie camera; the tape recorders are tested out, levels found and light meters read. Almost ready, a few last touches: Move a couple chairs and an ice chest full of Dr. Pepper into the bathroom, wrap anything that might prove noisy with towels, test the volume on the stereo so it won’t drown out bedridden grunting and such, hide everything that doesn’t belong there. Empty out the ashtrays . . . straighten out the bed. Wait again. Casey will call when they leave to come to the house. Waiting now, nervous energy forcing hurried searches for anything forgotten or done wrong. Test everything again. Bounce around on the bed to make sure the creaking springs come through on the tape.

Casey calls, they’re coming! Scramble. Lock the door, turn off the lights. Into the bathroom, bolt it, turn off the light . . . wait . . . You hear the door rattling as they come in, small talk in the living room. Get her a drink. Dudley has the earphones on, straining into the monitors to hear conversations in the living room (“Christ, what if she wants to do it in the living room where there aren’t any cameras.”) Robert turns on the stereo, at a pretested level that will muffle the sound of the movie camera without obscuring all that grunting, puts on enough records to last for hours.

They come into the bedroom. Nervousness, what if she sees that jury-rigged hole in the wall? She sees nothing. She is, in point of fact, rather single-minded at the moment. They undress, smoke a joint. She likes to do it in the dark, she says, but Robert convinces her to leave one of the lights on. Dudley gives them a while to get cranked up, listening on the earphones, timing himself. Nervously, gulping Dr. Pepper, tapes over a flashlight and turns it on, a soft yellow glow illuminating just enough to adjust the tape recorder. Time to open the slot and start taking pictures, adrenalin pumping, breathing fast, mouth dry, Jesus, what’ve she sees me when I move the cover?

Not a chance. She is, as they say, otherwise occupied, and her perceptive powers are not at their peak. Under normal circumstances, a camera loaded with super-fast, 1000 ASA film and fitted with a telephoto lens could take pictures right through an air-conditioner grating or a gauze curtain, and would be so mounted, but Katherine’s impatience has prompted a makeshift operation; that same impatience, though, makes her oblivious to peep-holes full of cameras.

Dudley is now taking pictures like mad, spelling the TV and movie cameras with three still cameras all fitted with different lenses, wide-angle, telephoto, zoom, changing film constantly, sliding new cassettes into the movie camera, all in utter darkness and much-practiced silence. He starts to relax now. Robert is tying her in knots, maneuvering into interesting photographic angles, looking up once in a while to smile at the peephole, waving one time, flashing the V-sign for peace or victory or whatever it stands for now, working his way through the Kama Sutra. Dudley smiles, laughs a little to himself.

Robert and Katherine break for another joint, Dudley shuts the slot; they turn again to their business, Dudley turns again to his, opening the slot and clacking away. Robert is going on six now, Katherine so far gone on sex and dope that anything beyond arm’s reach is outside her consciousness. Dudley is confident. He opens the bathroom door, dances quickly past the open bedroom door to go outside and try different camera angles through the windows. Coming back he stops brazenly in the bedroom door to crank off a few more.

Robert is still going strong, three hours now, still earning his pay. Dudley uncorks a Dr. Pepper and sips placidly, ambles into the living room to put on some more records, trading James Taylor for Bob Dylan. “He ought have about one more good one left in him,” he says, thereby underestimating his employee by about 40 percent. It’s creeping up on 5 a.m. now, boredom settling in, Robert aiming for a world record or something, Katherine wheezing badly, straining the capacities even of nymphomania. Dudley puts on some more records. Once, she hears the loud phhh-that of the Nikon shutter and starts, but Robert pulls her back down (the Nikon was pressed into service only in the flush of confidence and because of a special lens attachment; the standard surveillance camera is the silent Leica). Finally, with false dawn, nearing an end, Dudley’s in the kitchen, raiding the icebox, Robert and Katherine finally going to sleep. Pack up the equipment, put the film together to be processed, hide more stuff, clean up the bathroom. Split.

A week later Katherine is in domestic relations court for her show cause hearing, lawyer in tow, expecting to get the house, their son, and $100,000 to boot. All the parties and their attorneys are sent to a conference room. Dudley, pleasantly nodding to everyone, carrying two large briefcases. There follows a multi-media presentation the likes of which would make Andy Warhol proud, color & black-and-white, slides, stills, TV and movies, synchronized sound, two tapes, even James Taylor strumming languid guitar on the sound-track. The impact is fierce. Devastating. She will sign anything in front of her, wanting only to get out of there, away from those slides, movies, tapes, anything: custody, settlement, property, alimony. And it’s all perfectly legal.

“We don’t like to take domestic cases,” says Bell. “They’re usually pretty dirty and you always end up makin’ some real enemies. We only do ’em when the money’s real good.

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with running around some if you’re getting divorced, y’know. But most men have got a little pride and if you’ve got a picture of ’em with some old girl, well, they’ll settle a lot quicker.”

Divorce cases are the kind you don’t see many of on the tube. Can you see Buddy Ebsen hiding in a bathroom with a movie camera? But that’s how most private investigators make a living. Not counting the one’s working for big law firms or insurance companies, there are about 1,000 licensed private detectives in Texas and, just as a lot of lawyers that you don’t see make a living chasing ambulances and filing divorces, most private eyes subsist by snooping on spouses.

Few of them would ever get near cases as sophisticated as those Bell works—insurance fraud, patent theft, stock manipulations. Murder. He does, though, pull off an occasional case of the TV Good Guy genre.

Mrs. Beverly Magruder was deserted by her husband while she was in the hospital three years ago; he took their savings, their possessions, and their daughter Sharon. When she later won an uncontested divorce, the question of child custody was left in ephemeral legal limbo: Texas law makes no provision for the settlement of custody unless the child is in the state.

After remarriage to a man who brought to the match a rare empathy for the burdens of motherhood, Beverly re-embarked on a quest for her missing daughter. First stop was Dudley Bell. Bell spent, off and on, several months tracing the tortuous path of her ex-husband and Sharon from Houston, twice across the country to San Diego and thence to Atlanta. After several misfires Beverly and Dudley flew to Atlanta. Fearful that another disappointment would spark a breakdown, no one told her where she was going or why; she just went.

After incredible cloak-and-dagger nights and days, Beverly walked up to a parked car where her daughter, unseen for two years, waited while her ex-husband was shopping. “Sharon, mommy’s come to take you home.” She came, simply, amidst tears and bright eyes. Bell had a private plane waiting and a judge at a Houston airport to grant temporary custody. He still goes to dinner at the Magruders’, about once a month, and Sharon calls him “Yogi Bear” and sits in his lap.

“I’ll just never believe a bad word about Dudley Bell,” says Mrs. Magruder. “For six months he was the only hope I had in the world. He was all I had to lean on and he was always there when we needed him. He’s so sweet and personable—there’s a whole side to him that most people never see.”

Political Interlude

Setting: Houston, in the dark back alleyways of Power.

Characters: Jan, a young woman, sign of Capicorn, not overly attractive but exuding an intriguing sensual pulse, a volunteer political worker for the moment, normally employed in more earthy professions; and a youthful political candidate, handsome and aquiline, possessed of all the modern political attributes: witty, articulate, intelligent, a polished veneer of poise and class cloaking everything but the thin edge of awkwardness where his ambition abuts his immaturity.

Scene: Campaign headquarters.

Action: Jan goes to work as a headquarters volunteer, meets the candidate. On the second day they go to lunch. On the next they go to her apartment where a third, unseen, character is in the closet, with a peephole. Hmmmh . . . .

Dialogue: Minimal, improvised. Small talk, sexual noises.

Epilogue: Various photographs end up in the office of an editor of one of Houston’s daily newspapers. Being a family paper, the editor declines to print them, rather inviting several “prominent citizens” to various private showings. The Selling of the Candidate.

Coda: Dudley Bell’s politics are essentially mercenary. The job in question was taken for cash, like all the others. “I been sorry ever since. That was one of the biggest mistakes I’ve ever made. It’s done nothing but cause me trouble and cost me a fortune in lost business.” He figures as well that it’s cost him a couple of indictments: “That’s what’s causing me these legal problems. [———-] has got supporters in the police department who’re hot to get me.”

Bell has only done one other even semi-political case: A friend of his was campaigning against the police commissioner in a little suburban township. Bell dug back into the hapless incumbent’s closet and found that the poor bugger had flunked out of A&M in his freshman year. He got a copy of the official transcript, had it printed up as a placemat, and passed out 5,000 of them. He’s surprised that he doesn’t get more calls from politicians.

His observations on the Watergate Caper: “Those guys were so dumb, I mean really amateur. If I had the kind of money they had, and access to the kinds of equipment they had, I hate to think about what I could’ve done. And then they got caught, for taping over a door lock. That’s really bush league.”

More so than most professionals, the work of private investigators takes place in that nasty nether world that most of us don’t even know is out there. Continued expeditions into that criminal dimension serve naturally to harden a man, to exact their toll from his sensibilities in the same manner as continued skin-diving will do it to his lungs. Bell sees himself as a professional, among the best in his profession, and the standards he abides by are professional ones: A job is good or bad only insofar as it is done cleanly, quickly, and legally, and more subjective moral scruples rarely enter the picture.

He will, on occasion, do a turn in behalf of his fellow man. He’s done cases for free when he’s felt like it, once took a turkey in payment for two weeks work tracing the disappeared daughter of a rural couple. For a client in Oklahoma he recently traced down 29 million barrels of available crude oil, and sees that as a blow for consumers.

Sixteen years ago a famous Western actor came through town to star at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo. He left, no doubt inadvertently, something behind, and Dudley Bell was discreetly hired to verify the consequences. For 15 years now, he’s continued to drive by the house, unpaid but concerned, where the movie star’s daughter is growing up.

Like all the rest of us, he’s just trying to make it.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Houston