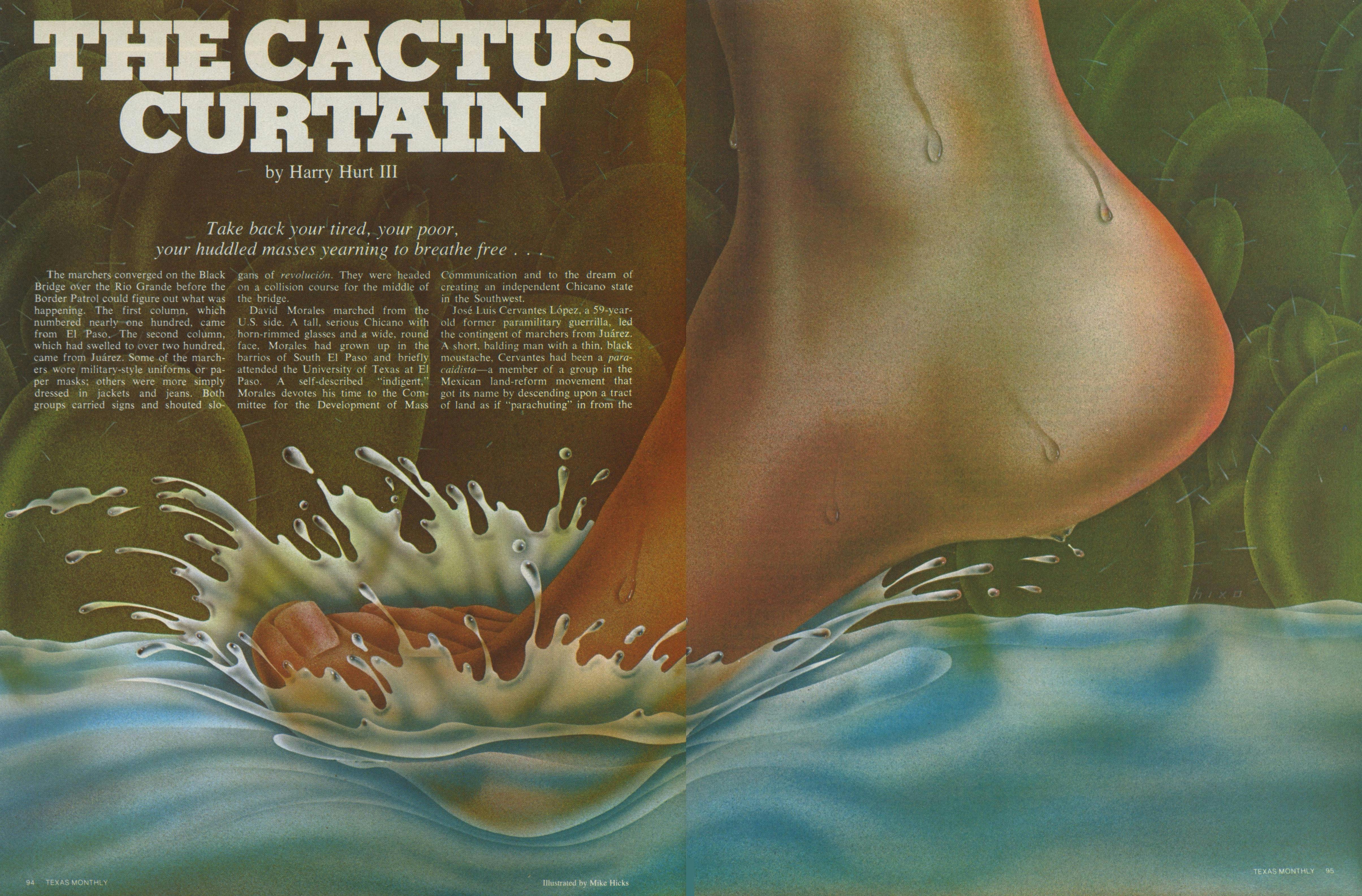

The marchers converged on the Black Bridge over the Rio Grande before the Border Patrol could figure out what was happening. The first column, which numbered nearly one hundred, came from El Paso. The second column, which had swelled to over two hundred, came from Juárez. Some of the marchers wore military-style uniforms or paper masks; others were more simply dressed in jackets and jeans. Both groups carried signs and shouted slogans of revolución. They were headed on a collision course for the middle of the bridge.

David Morales marched from the U.S. side. A tall, serious Chicano with horn-rimmed glasses and a wide, round face. Morales had grown up in the barrios of South El Paso and briefly attended the University of Texas at El Paso. A self-described “indigent,” Morales devotes his time to the Committee for the Development of Mass Communication and to the dream of creating an independent Chicano state in the Southwest.

José Luis Cervantes López, a 59-year-old former paramilitary guerilla, led the contingent of marchers from Juárez. A short, balding man with a thin, black moustache Cervantes had been a paracaidista—a member of a group in the Mexican land-reform movement that got its name by descending upon a tract of land as if “parachuting” in from the sky. Now he was associated with the Alianza of Juárez, a coalition of activist groups ranging from revolutionaries to mainstream socialists. A man of byzantine connections, Cervantes was rumored not only to be a close friend of the governor of Chihuahua but also to be wanted by Mexican federal agents.

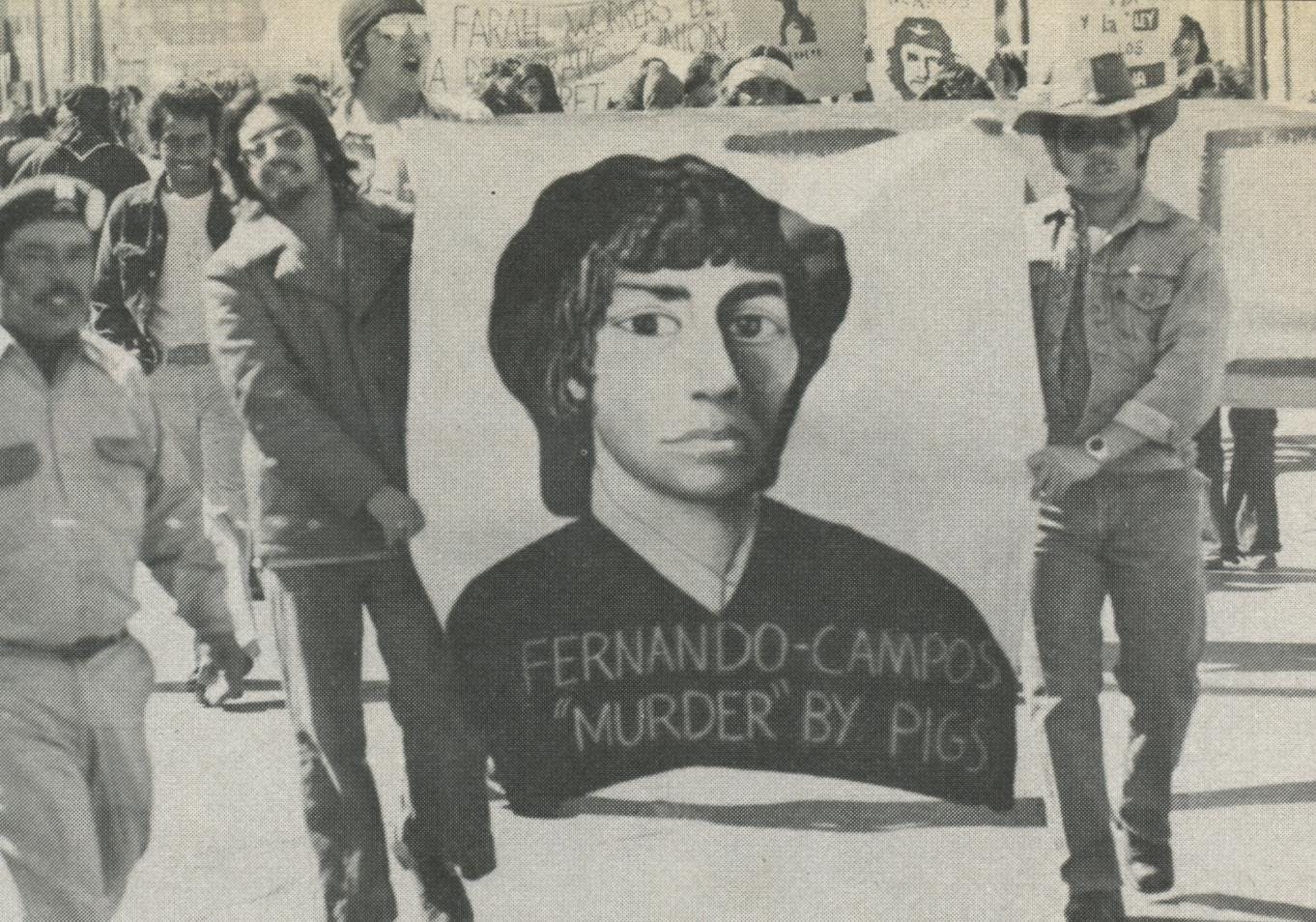

The ostensible purpose of the march was to protest the deaths of two young Mexican nationals allegedly killed by the U.S. Border Patrol. One of the youths, Manuel Soto Flores, had met his death on the Black Bridge. A favorite crossing point for illegal aliens, the Black Bridge was no more than a Santa Fe Railroad trestle with black steel sides. In addition to being a hazard for illegal aliens, it had claimed the life of one U.S. Border Patrol agent who slipped through an uncovered gap in the ties and fell into the concrete channelized riverbed below. The meeting at the Black Bridge also marked the coming together of the Juárez Alianza and the Chicano activist groups of El Paso, a symbolic show of ethnic and ideological solidarity. “We talk a lot about our common homeland, but sometimes the mexicano thinks we have sold him out,” David Morales would explain afterwards. “At the Black Bridge, we decided to meet halfway. We wanted to show that we don’t recognize political boundaries, that we can cross back and forth at will.”

As usual, the Black Bridge was guarded by a small contingent of green-uniformed Border Patrol regulars. Since the announced parade routes of the demonstrations had not included the bridge, the agents had been caught unprepared. They were armed with guns, sticks, and a few riot-control helmets, but a hasty call for reinforcements had managed to swell their numbers to only about ten.

When the marchers reached the middle of the bridge, they exchanged greetings and pledges of allegiance and began to mix. Behind them, on the north side of the river, rose the bank towers of downtown El Paso and the graffiti-engraved peaks of Mount Franklin, the lower tip of the San Andres Mountains. Behind them, on the south side, the Juárez commercial district ran into the red-light district and then into the slum colonies—the colonias—which spread from the riverbank to the foothills of the Juárez Mountains. A few yards down the river the routine traffic of cars and people crossed the high-arching Paso del Norte Bridge. After a few words, the crowd split into two groups and began to leave. The group returning to the U.S. side ran smack into the Border Patrol.

“The minute we made eye contact, we knew it would be the stick,” David Morales recounted later. “The Border Patrol wanted to show who was boss. They just assumed that some of the people were crossing illegally. They tried to sort us out. They started shoving, then some rocks started flying, and then they brought out their sticks.”

The riverbank went wild. The demonstrators charged across the bridge shouting, “¡Muerte la migra!” (“Kill the Border Patrol!”) and “¡Es nuestra patria!” (“This is our country!”). The Border Patrol managed to shove a handful of the demonstrators into a waiting van, only to stand by as the mob kicked in the sides of the van, smashed the windows, and freed the prisoners. A call for help went out to the El Paso police, but there was no immediate response. Rocks and dust and sticks were flying everywhere. The fight raged for nearly a quarter of an hour—just about the same length of time as the charge that won the Battle of San Jacinto. Finally, a quick, disciplined stick surge by the Border Patrol forced most of the crowd back across the bridge.

By the time the air cleared, one Border Patrol agent had been seriously injured in the head by a rock, and two Border Patrol vehicles had been badly damaged. The number of casualties among the demonstrators was never officially estimated, but there was only one arrest: José Cervantes López, the United States’ newest illegal alien.

Cervantes warned that if he were not released, he would give the signal for 20,000 of his supporters in Mexico to charge across the river to rescue him. Cervantes was not released and no Mexican invasion occurred. A few days later, with the help of an influential El Paso attorney, Cervantes was deported to Mexico.

The battle at the Black Bridge took place on March 9, just about the same time the national news magazines were focusing on our Mexican immigration problems, Leonel Castillo was being confirmed as head of the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service), and news of the Carter administration’s amnesty and tight border proposals was leaking into print. Dale Swancutt, chief of the El Paso Border Patrol station, called the situation “explosive ” and pleaded for more men, more money, and a seventeen-mile concrete-posted fence-and-canal system to help keep illegal aliens out. The incidence of violence along the once lackadaisical border has increased ever since.

What was a few months ago a “border crisis” precipitated by a “silent invasion” of illegal aliens now shows signs of escalating into an undeclared border war. Mexican aliens have attacked the Border Patrol with rocks, sticks, shovels, tools, and steel ball bearings fired from slingshots. Small bands of agitators regularly roam the southern bank, and there is some sort of confrontation nearly every week. Although Border Patrol agents, regular illegal river crossers, and local activist groups dispute the specific facts of many of these cases, all agree that the river has become a battleground. There has been a general decline in fear of, and respect for, la migra. One Border Patrol agent has already fired his gun to scare off a group of rock throwers he claimed had him pinned down. Some agents now say it will only be a matter of time before they will be forced to kill in self-defense.

Meanwhile, the press of people against our southern border continues. Last year, the El Paso Border Patrol station apprehended just under 125,000 illegal aliens, more than 90 per cent of them Mexicans. Nationwide, the figure was approximately 875,000. This year, the El Paso station reports that arrests are averaging 12,000 to 13,000 per month, and officials expect that the national total for 1977 will exceed one million. There is simply no way of telling how many get away. But using arrest rates as at least a rough indicator of the traffic flow, Border Patrol officials estimate that the number of illegal aliens already in the country is between four million and eight million and growing. Rapidly.

The overwhelming dimensions of this influx are exceeded only by the overwhelming frustrations inherent in any attempt to stop it. Indeed, a typical ride along the Rio Grande with the Border Patrol merely underscores two facts that many El Pasoans have long taken as common knowledge: (1) stopping or even slowing the flow of illegal aliens into this country without spending millions of dollars and imposing quasimilitary conditions along the border will be almost impossible; and (2) stopping or significantly reducing the flow of illegal aliens could have seriously disruptive, if not devastating, effects on El Paso and its sister city, Juárez.

Ray Russell swung his light green, government-issue Ford Custom up the gravel embankment of the levee and turned west toward downtown and the ever-shimmering sun. Off in the distance, in the gap that formed between the Franklin Mountains and the Juárez Mountains, the glass bank towers of El Paso and the huddled old buildings of Ciudad Juárez seemed to run together as if they were simply disparate slices of the same city. But here by the river’s edge, just above the tiny and ancient community of Ysleta, the demarcation line was clearly visible.

“That’s the mighty Rio Grande,” Russell smirked, as he motioned out his window. “You can see what an obstacle it presents to someone who wants to come across.”

The stretch of river he pointed at was a green, winding line about thirty feet wide and, by the looks of it, perhaps three feet deep, about the dimensions of an average-sized bayou or a large drainage ditch. The riverbed and banks were lined with concrete. An open grassy space a few yards wide ran between the riverbank and the levee, but there were no barriers of any kind. On the Mexican side, the land was flat and overgrown with scrub and high weeds. To our right, across the border highway on the U.S. side, a strip of run-down adobe houses blended into a cluster of steel-pipe petrochemical stacks, which led to the redbrick tenement rows of South El Paso’s segundo barrio. The only sign of life was a brown-and-black mongrel trotting purposefully after scraps of food in the trash and paper along the near bank.

“All the cities west of here have fence,” Russell complained as he continued up the levee road. “But along this stretch there is only the river and the river is no deterrent at all.”

Russell spoke from experience. A slow-moving, weather-beaten man with a potbelly and a yellowed smile, he is a career Border Patrol agent. After working the Canadian border, he spent thirteen years in Chula Vista, California, the busiest crossing point, where he became patrol agent in charge, the Border Patrol’s equivalent of a frontline field commander. Like most of his fellow men in green, Russell has been pushing for the construction of a fence-and-canal system along the heavily populated strip between El Paso and Juárez.

“If we had some kind of barrier, at least we’d have a chance of stopping ’em from coming across,” he declared. “The way things are now, they just blend into the neighborhoods as soon as they leave the river. It’s ridiculous.”

Just then a covey of dark-haired figures scurried across the road about fifty yards ahead. Russell depressed his accelerator and reached down for the radio. “Forty, forty-eight, eighteen to any unit in the area: looks like we’ve got five or six wets down by the garbage disposal plant,” he announced to the microphone. The speaker crackled, but there was no reply. Russell drove faster.

By the time he pulled up to the area by the domes of the garbage disposal plant, six teenage boys in jeans and T-shirts were scrambling down the steep bank on the U.S. side. Meanwhile, two other men on the Mexican side were in the process of rolling up their pants legs, two older women and a middle-aged man were sitting along the bank on the U.S. side as if enjoying a picnic, and a woman in a flower- print dress and a wide, white hat was attempting to wade across, carrying a blue bag in one hand and mindfully securing her hat with the other.

“¡Váyanse para atrás!” Russell shouted at the teenagers. “Go back across!” The two stragglers of the group smiled back and waved, then hurried toward the river. The woman with her hand on her hat kept coming. Russell started down the road again. “Forty, forty-eight, eighteen to any unit in the area,” he radioed again. “We just ran a bunch of ’em back. They’ll probably try again in fifteen minutes.”

The scene repeated itself about every half-mile. Five or six Mexicans were about to cross, another ten or twelve were fleeing for the cover of the barrios a little further upriver, and three more were wading in the water, eyeing the green Ford as it rolled past. By the time he reached the Chamizal Island area, Russell had shouted back at least 25 people trying to cross the border in broad daylight, most of them dressed in casual shopping clothes or jeans.

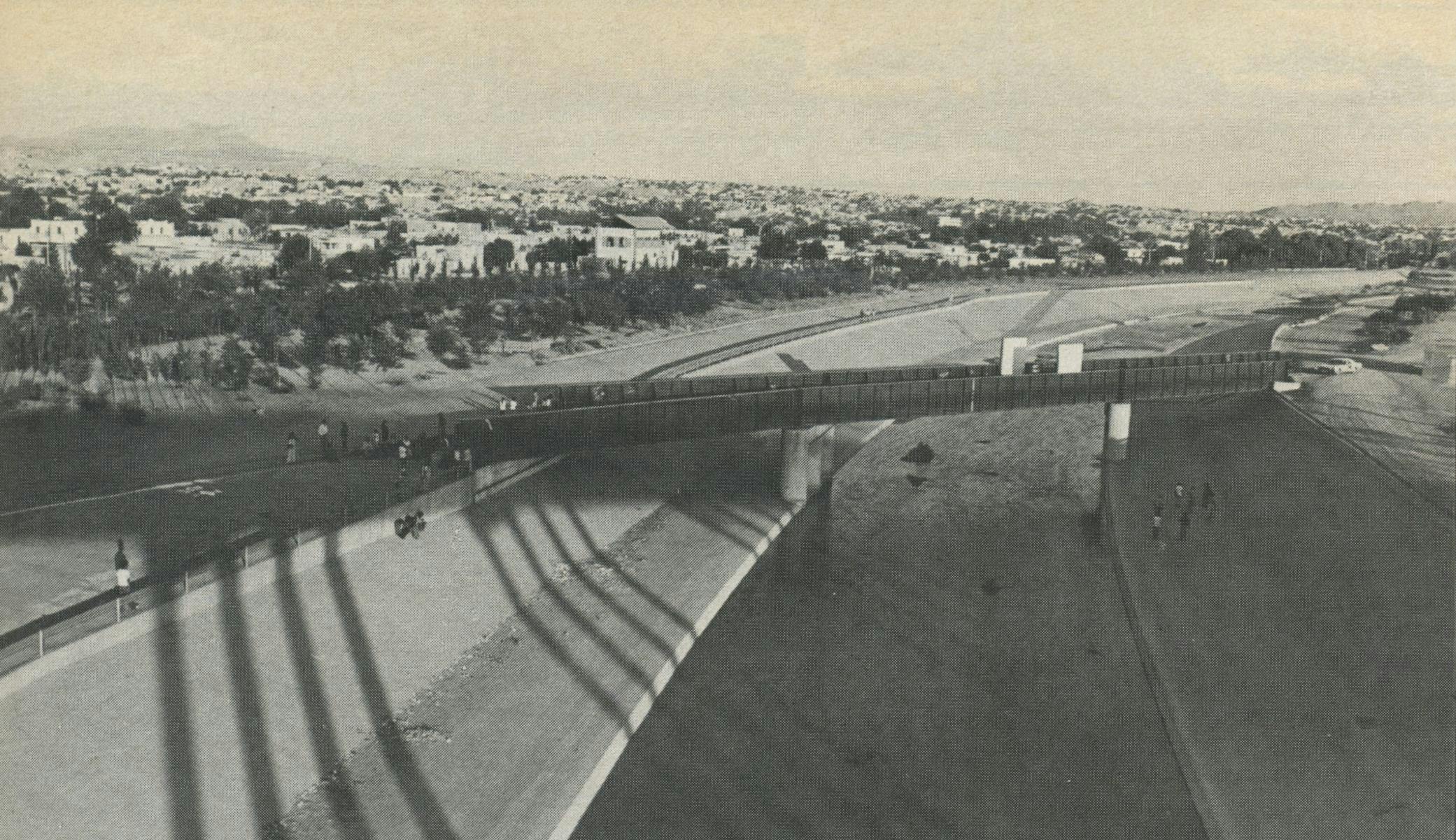

He pulled up near the pillars of the high-arching Cordova Bridge and gestured across the arid flats to the left and the barrios to the right. “This Chamizal area is part of the land that President Kennedy agreed to give back to Mexico after the river changed course,” he said. “They had to rechannel the river and relocate about three thousand people. In the early morning, this is one of the busiest crossing points for illegal aliens. You can see forty or fifty at a time lining up to come across. We can always get a few of ’em, but when they run in all directions at the same time, it’s impossible to stop ’em all.”

Russell drove on past the railroad yards and the new Bowie High School and the warehouses and the downtown buildings on the right and the adobe houses of the colonias on the left. Along here, near the downtown area, a cyclone fence ran for about two and a half miles, and a concrete canal with deceptively deep and swift water paralleled the fence a few yards closer to the highway. However, the fence was battered and riddled with large holes in many places, and the canal, where several suspected illegal aliens had already drowned in the last year, turned away from the Rio Grande after only a mile or so.

Russell pointed to the black railroad trestles on either side of the Paso del Norte Bridge. The first trestle was blocked by a high white gate with skirts that overlapped each side of the railing. The second trestle, the infamous Black Bridge, was wide open. A light green Border Patrol van waited at the U.S. end. That very day the Santa Fe Railroad, which owned the bridge, was in the process of losing a suit brought by the INS to have the railroad put up a gate.

“You see, once they make it over the bridge, all they have to do is hop a freight train,” Russell explained. “Then they’re gone to Chicago or anywhere. I’ve seen as many as a hundred and fifty people lined up to cross at the Black Bridge. The taco vendors come out and it gets to be kind of like a carnival. Unfortunately, since the recent incidents of rock throwing and so forth, the carnival atmosphere has kind of disappeared.”

A few moments later, Russell stopped at the Franklin headgates to check in with the agent on duty. Here the river was barely a hop, skip, and jump: about fifteen feet wide and only a foot and a half deep. There was a canal behind the river on the U.S. side, but no fence. Six young people, three males and three females, were sitting by the water on the Mexican side.

Russell talked briefly with the agent, then drove on slowly until we came to the western edge of the city where the river turns north and the borders of Texas, New Mexico, and Mexico come together at two brick plants. To the west there is little but arid flats and low sandhills dotted with scrub, a few clusters of houses and low buildings, and the bleachers of Sunland Park racetrack.

The border is marked only by a series of short, white pointed markers spaced half a mile apart. Except for an occasional ranch fence and the fences at the cities, there is no significant barrier from the brick plants to the Pacific Ocean. Instead, the Border Patrol has installed Viet Nam-vintage electronic sensors along the U.S. side. Though Russell and other agents believe in their usefulness, these sensors are tripped off by everything from raindrops to passing cows, and they merely detect movement across the border, they do not prevent it.

“We have 360 border miles and 84,795 square miles in the El Paso sector,” Russell said, looking into the distance.

“We engage in all types of activity except boats. But our total force is only about 280 active agents. With vacations and sick leaves, that works out to about 40 men per shift for the entire area. I need that many men just to patrol the river.”

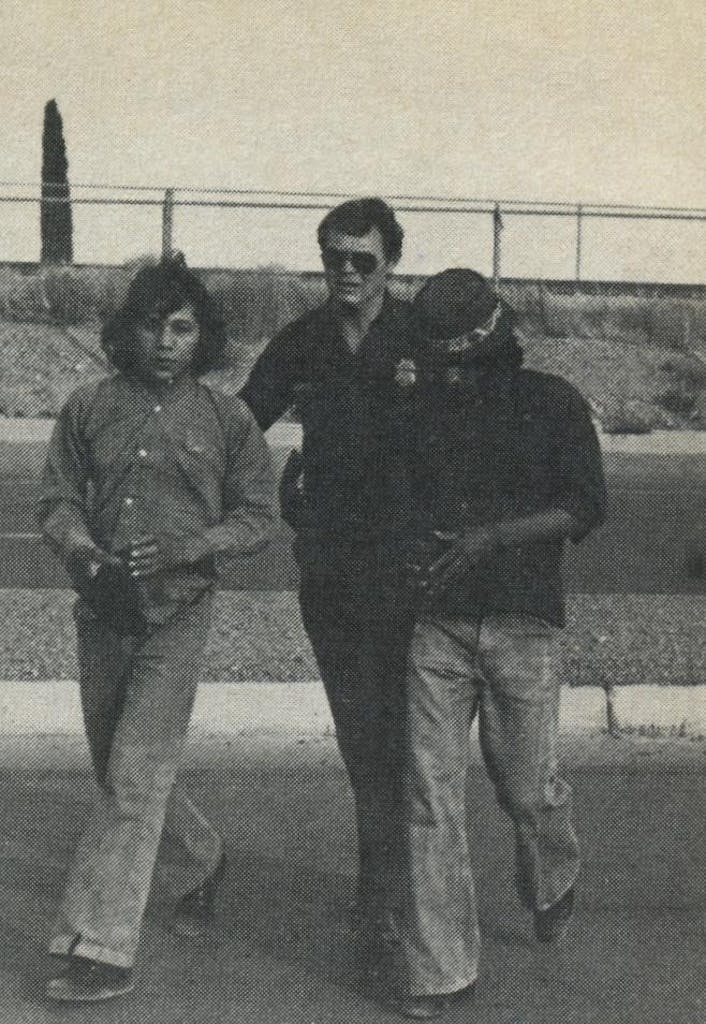

At this point Russell spotted some movement at the edge of some nearby sand hills. He stopped the car, got out, and walked back a few yards toward a little gully. All he could see was scraps of trash paper swirling in the wind. He shook his head, climbed back into the car, drove twenty yards, and stopped again. This time he started up the side of one of the hills. All of a sudden, two heads emerged from behind a rock, and two teenage boys in jeans and light jackets came walking down the hill. One wore a blue cap, the other a red bandanna. Russell said something in Spanish and motioned for them to get in the car. They obeyed docilely.

“It’s a good thing they didn’t try to run,” Russell said with a grin as he got back in the car. “I probably never could have caught them.”

As it turned out, the boys had been headed for Anthony, a small town on the Texas-New Mexico line, where they hoped to find work as pickers. Both said they had been arrested once before, one of them only the previous day.

“Mala suerte,” Russell chuckled in an almost fatherly tone.

“Si, mala suerte” one of the boys replied. This was “bad luck” indeed.

The brutality of the U.S. Border Patrol is a subject of legend in Mexico and in the barrios of South El Paso. Long before the recent border violence, there have been regular complaints that agents randomly beat aliens, that they hassle attractive Mexican women, and that their fabled midnight raids and frequent spot checks are based on no more probable cause than the fact that a suspect has dark skin and brown eyes. But these two teenagers seemed calm, not hostile or scared, just tired and disappointed.

The statutory offense for entering the U.S. illegally the first time is a misdemeanor punishable by six months in jail and/or a $500 fine. Entering the country illegally a second time is a felony that carries a penalty of two years in jail and/or a $1000 fine, but as a practical matter the boys did not face anything so severe.

“They know we’re not going to do anything to ’em except book ’em and bus ’em down to Ysleta where they can go back across,” Russell said as he drove back toward the Paso del Norte detention center. “We’ve got so many that the U.S. magistrate doesn’t even want to take the time to prosecute them unless they’ve been caught three or four times before.”

Had they been smugglers of illegal aliens the story might have been different. Those who harbor or transport illegal aliens face a penalty of not more than five years in prison and not more than $2000 fine for each illegal alien.

Russell conceded that there had been isolated incidents of Border Patrol misconduct in the past, but he denied any systematic viciousness. “We’ve already processed over eleven hundred aliens in the first four days of this month in the El Paso area alone,” he pointed out. “When you consider the number of men we have and the volume of traffic we handle, we have a much better record than any police department in the country even if you assumed that every allegation made against us were true.”

A short time later, Russell turned into the parking lot of the tan block building that houses the Paso del Norte detention center. He led his two captives into the booking room, a cool, dark green corridor with a wire partition at one end and two simple cell-blocks along one side. Along the other side were several gray metal desks manned by agents interviewing the most recent arrestees. Only a handful waited behind the wire partition and inside the two cellblocks.

Russell left the two boys in the custody of one of the agents on duty and returned to the car.

“I’m sure we’ll see those two again,” he sighed. “They’ll probably try to come back across again tomorrow. You know, sometimes when I think about it, I don’t even want to come to work in the morning.”

It is easy to appreciate Russell’s frustration. What we saw was merely a sampling of the midday traffic. The rush hour actually begins, if it is indeed possible to pick a beginning and an end, in the predawn darkness around 2:30 when the busboys, bartenders, and barmaids who work the U.S. side start to make their way back to Juárez, and the farm workers and ranch hands arrive at their pickup stations in the gray parking lots’ near the Paso del Norte Bridge. All night the bushes are alive with people ducking, darting, crawling, crouching, and running toward prearranged meeting points with “coyotes”—the professional people smugglers who pack their cargo tight inside U-Haul trailers and truck them north to factories in Denver, Saint Louis, Boston, and Newark. By dawn, the maids and cooks and gardeners, the professional workers, and the freelancers bound for points north line up at the bridges forty, fifty, and a hundred at a time, some in the white uniforms of domestic servants, others in suits and ties or dresses. Indeed, by the time Russell dropped off the two teenagers at Paso del Norte detention center, the flow had come full circle. The farm workers and ranch hands had begun to return from the fields carrying their jackets and extra shirts, and the bartenders and barmaids had just started to come across for another night’s work.

Attempts to characterize the typical illegal alien are hampered by the basic difficulty of identifying and counting all of them. Judging by those who are caught, most who enter the country illegally are agricultural or domestic workers, who, like previous streams of immigrants to America, come virtually penniless. But increasing numbers are doctors, professionals, and skilled and semi-skilled workers who carry several hundred dollars with them, even after paying several hundred for a coyote to smuggle them across. Most of them are bound for the interior U.S. and, in 70 per cent of the cases, for one of seven states: Texas, California, New York, Illinois, New Jersey, Massachusetts, or Florida.

In El Paso, as in other Texas border towns, illegal aliens are an integral part of the lifestyle and work force. Indeed, from the days when Apaches roamed the land around the river, through the days of the Spanish conquerors and the first Anglo settlers, the flow of goods and people between El Paso and Juárez was cyclical and fairly unrestricted. It was not until the 1880s, when the railroads brought in carloads of Chinese laborers, that the border began to be tightened. Soon afterwards, considerable attention was aimed at stopping the flow of European immigrants through Mexico—a move largely directed at Arabs, Irish, and Jews—chiefly by means of literacy tests. Mexicans, however, were not impeded by the simple literacy test. Many entered the U.S. and soon found work on the surrounding ranches. Ironically, many of El Paso’s prominent Arab and Jewish commercial families entered the country illegally via Mexico.

The first great wave of Mexican immigration occurred between 1910 and 1914, during the Mexican Revolution, when an estimated four million people streamed across the Rio Grande. But for the next fifty years, U.S. labor cycles determined the northward flow. Dr. Ellwyn Stoddard of UT-El Paso has identified the major influxes prior to the current one that were stimulated by U.S. economic needs. The first was during World War I, when a shortage of labor led to a temporary open border policy. Large numbers of Mexican workers soon appeared on the farms and ranches of the Southwest. However, when the Depression hit, most of these workers were kicked back across the border.

World War II brought Mexican workers back to the United States in the greatest numbers since the Mexican Revolution. According to Stoddard, some three million Mexican aliens entered the country while the U.S. was at war with Germany and Japan. Then, in the late forties returning servicemen swelled the job ranks again, and in the early fifties the government began Operation Wetback, an unprecedented human round-up that resulted in the deportation of almost three million people in three years. The Eisenhower administration attempted to improve the border situation by formalizing the bracero program, which had been in effect off and on since 1942. Under this plan, hundreds of thousands of Mexican workers were brought into the country on a temporary basis with the approval of the Labor Department and the INS. The hope was that they would learn skills they could take back to Mexico to improve conditions there while at the same time serving the needs of local farms and ranches. However, in 1964, Congress ended the program after persistent pressure from organized labor claiming that illegal aliens were taking jobs away from Americans.

The illegal alien situation has been unmanageable ever since. With the termination of the bracero program, the flow of people across our southern border ceased to be governed by our economy and our labor needs. Now the impetus to move north comes ever more strongly from Mexico. With the world’s highest birthrate, Mexico grew from forty million to over sixty million people in just ten years. Unemployment remained over 30 per cent, and neither the archaic patron system nor the burgeoning bureaucracy could provide basic food, clothing, housing, education, health care, or jobs. Mexico soon had a world-record national debt to go with her world-record birthrate. Out of fear and frustration, the rich began sending their money out of the country. Out of hunger and desperation, the poor turned to America.

Though the vast majority of illegal aliens who enter the country at El Paso are bound for the U.S. interior, an estimated 60,000 have chosen to remain in the El Paso area. In a city of 400,000, where over half the people have Spanish surnames, illegal aliens constitute a hefty 15 per cent of the population. Not surprisingly, they blend easily into the culture and commerce of the city, receiving both tacit and active support from institutions ranging from local business to the Catholic Church.

With the notable exceptions of the U.S. Army and clothing manufacturer Willie Farah, practically every major employer in town is known to make a practice of hiring substantial numbers of illegal aliens. In addition, the greater portion of the farms, ranches, and food-and-drink establishments in the area are run on the strength of illegal alien labor. As INS Criminal Investigator W. F. Mayberry put it in a recent interview, “We could spend all our time just busting bars and restaurants.”

Most illegal aliens in El Paso are employed as maids, gardeners, and domestics. According to INS estimates, there are at least 15,000 illegal maids in the El Paso area, and, if the testimony of local householders is to be believed, there could be twice that many more. “Practically everyone in El Paso has an illegal maid,” declared one prominent local attorney recently. “And every illegal maid has her own maid in Juárez.”

In the old days, El Paso’s economy was built on the four Cs: cotton, copper, cattle, and climate. Today, the city’s economic stability also relies on cheap labor, and illegal aliens are clearly the cheapest of the cheap. The INS estimates that about 30 per cent of the illegal aliens employed in the area make over $2.50 an hour; the rest generally make much less. The average wage for farm and ranch stoop labor is said to be about $1.75 per hour. The going wage for an illegal maid is about $25 a week. But then, as many are quick to point out, this is about twice to three times as much as the same workers would earn in Mexico—if they could find jobs at all.

For illegal aliens who rise from poverty, El Paso offers considerable advantages and opportunities. For one thing, it is one of the most integrated cities in the U.S. A large portion of the poor Chicano and illegal alien population is clustered in the barrios south of Interstate 10, but better homes are available to Mexicans and Mexican Americans who can afford them in virtually every part of the city. The same holds for the city’s blacks and other minorities. The U.S. military presence at Fort Bliss (over 10 per cent of the city’s work force is on the military payroll) and the nearby scientific community of White Sands, New Mexico, have exerted a nationalizing, homogenizing influence on this otherwise isolated desert oasis. The city is by no means free of discrimination, but the days of the “No Mexicans or Dogs” signs are gone. Bilingual education and busing to improve the ethnic balance in the schools are still emotional issues, but Chicanos and Anglos seem to get along with each other much better than in cities like San Antonio and Houston. Ray Salazar, the city’s Chicano mayor, was elected not because of his ethnic background but because of his experience as a CPA and his opposition to higher utility rates. The kingmakers of old El Paso—families like the Schwartzes and the Youngs—still exert influence over what happens economically and politically, but with the recent advent of single-member districts, their power is clearly on the wane. As a result, many second- and third-generation descendants of illegal Mexican immigrants have carved comfortable niches in the social structure as businessmen, professionals, and university professors.

Still, the subject of illegal aliens has always had class, economic, and racial overtones. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the well-appointed homes of El Paso’s Coronado district, where a newcomer who suggests that there might be problems or hypocrisies with using illegal alien labor may be backed into a corner, where his logic will be tied into hopeless knots. Ironically, once the infidel has been defeated, the discussion has been known to degenerate into a bragging contest over who pays his maid the least.

El Paso National Bank president Sam D. Young, Jr., has expressed the old El Paso point of view several times in the press: he recently declared that Mexican women are good workers at tedious jobs. Though his comments enraged local Chicano groups, Young claims he actually meant nothing derogatory. A second-generation El Pasoan who grew up on a ranch, Young learned Spanish before English; his teacher was the family’s illegal alien maid. “I employ an illegal alien maid now, and I see nothing morally wrong with it,” Young declared in a recent interview. “These people come looking for work, and they are willing to do jobs no one else will do. Labor has priced itself right out of the market. Where else do they expect industry to turn but abroad?”

Here the debate begins. Local labor leaders, like their national-counterparts, claim that illegal aliens do take local jobs, and they say that they think U.S. industry should look homeward. “We need to take care of our own people before we start worrying about Mexico,” says Luis Rosales, a Mexican American who is president of the Central Labor Council. “I feel sorry for these people. My own bloodlines go back to Mexico. But we can’t be expected to feed the world. The idea of America as a nation of immigrants might have been good a hundred years ago when we needed bodies to fill the plains, but now we have an overflow of bodies. Right here in El Paso, the unemployment rate is really bad. The Texas Employment Commission puts it at 12.9 per cent, but that’s not counting construction workers. By my estimates it’s closer to 15 per cent. Illegals are taking jobs our people need.”

In the past, the local media have been rather perfunctory in coverage of the illegal alien issue, generally avoiding the sort of investigative reporting that would upset the status quo. Lately, however, the newspapers have seemed to join the forces of organized labor in emphasizing the problems created by illegals. Recent stories have held wetbacks accountable for everything from rising crime to rising taxes. The El Paso Times, for example, reported that the cost to taxpayers of holding illegal aliens in the city jail was $45 to $65 per taxpayer, or about $4.9 to $9.2 million per year. Other stories in that same paper have blamed illegals for rising crime in the Sunset Heights district and for swelling the welfare rolls.

Local Chicano activists decry this as racism. “The media in this town regard illegal aliens as criminals,” complains David Morales. “These so-called illegals are simply undocumented workers who want jobs. They are like every other group that has immigrated to America. They are more like refugees that have in one way or another been separated from their homes because of war.” Morales says he thinks the United States should end all immigration quotas, rather than strengthen the Border Patrol. “The way the government is going at it,” he says, “is like trying to solve juvenile delinquency by beefing up the police force.”

Of course, the most common reaction to this issue in El Paso has been to point a finger at Mexico. “We’re not going to get anywhere toward solving the illegal alien problem until they clean up their act down there,” says a prominent local attorney. “Not only do they have enormous social and economic problems, but they also refuse to accept bilateral foreign aid, they put limitations on foreign investment, and they do just about everything they can to stay backward. About the smartest thing the government does is encourage the traffic of illegals, chiefly by not bothering to do anything about it.”

Arturo Castellanos shook his head vehemently. Mexican law, he explained through a translator, specifically forbids the smuggling of illegal aliens into the United States. Anyone who does so, either for himself or for others, can be punished with two to ten years in prison and a fine of 10,000 to 50,000 pesos. As chief of the Mexican immigration office in Juárez, Castellanos had considered this matter many times before. “The problem,” he continued, as he got up from his large wooden desk and started toward a stack of metal file cabinets, “is that we have to catch them.”

Castellanos would seem to be in a very good position to do that. A clean-shaven, baby-faced man in his early thirties, he works in a well-equipped modern government office building at the southern end of the Stanton Street Bridge, a location that puts him right in the middle of the border traffic. Unfortunately, as his own records showed, Castellanos and his men had been able to make a total of only five cases against illegal alien smugglers in the first half of this year.

“The big problem over here in Mexico is jobs,” Castellanos continued in between shuffling papers. “Mexico is trying to solve this problem. But the American government should also punish the employers of illegal aliens in the United States who pay low wages to the illegal aliens for hard labor.

“We have a problem here with people who sell counterfeit green cards which permit entry into the United States,” Castellanos said as he smoothed the front of his embroidered yellow shirt. “But we also have many complaints from people who say they were abused by the American Border Patrol.”

Castellanos gestured toward a map of Mexico on the wall. “You must also understand,” he said, “that we have our own illegal alien problem. People come into Mexico from Panama, Guatemala, and many other countries. Just here in Juárez we’re talking about twenty-five to fifty people per month. Right now, we are investigating everybody who comes in from the south to see if they have enough money to stay as a tourist or if they can work. If not, we are returning them in buses.”

Ciudad Juárez dramatically demonstrates the dimensions of his country’s immigration problems. Since the midsixties the city’s population has nearly doubled. Now Mexico’s third-largest city and biggest border town, Juárez officially contains half a million people, plus many more the official census takers miss.

Meanwhile, many of Juárez’ roles are changing. The border town was once one of the world capitals for abortion and quick divorce. However, changes in U.S. abortion laws and government directives from Mexico City regarding issuance of divorces have caused these formerly lucrative dealings to wane. In its efforts to bolster the border economy and to attract more tourists to Juárez, the Mexican government has instituted the Programa Nacional Fronterizo, or ProNaF, a border revitalization program that in Juárez consists of two large industrial parks and a cluster of air-conditioned shopping malls.

Apart from the lush green islands of the old ornate mansions in the central city and the sweeping Japanese and French provincial and neo-cubist architectural flourishes of the homes in the campestre district, the common element of Juárez is brown dust. Adobe colonias rise out of the sand hills and stretch up into the arroyos south of the city. Most of the housing is unspeakably overcrowded. In a nine-by-five room, ten or twelve people sleep in rows across the floor. In some parts of the city, conditions are more miserable. At the Juárez garbage dump, for example, over three hundred people make their homes in shanties, scrounging for food among piles of rubbish.

The poverty of Juárez is eloquent testimony to the magnetic attraction of the border. Of the thousands of new immigrants into the city from the interior, only a fraction make the crossing into the U.S. economy and—for them—undreamed of prosperity. The Irish ports during the great exodus of the nineteenth century must have been something like this. Unemployment is already over the Mexican national average of 30 per cent and growing higher with every new person. Each successive wave of people from the south further crowds housing, streets, hospitals, and jails. With the devaluation of the peso, both personal and municipal economies went into a tailspin, as new and old citizens found that their money could buy only about 60 per cent of what it could last August.

The best thing the Mexican government has done in an effort to provide long-term employment along the border is the maquiladora or “twin plant” program. Initiated in 1965 shortly after the U.S. terminated the bracero program, the maquiladora program now includes over 85 foreign corporations, many of them prestigious outfits like RCA, AMF, and General Electric. The companies operate under a special law that exempts them from the usual prohibitions against foreign ownership and allows them to own and control 100 per cent of their investments and the land on which their plants are built. Companies that manufacture items like TV and radio components, for example, can send the “raw materials” into Mexico and assemble the finished products south of the border without paying a duty. Going back into the U.S., products made in the plants are taxed only on the basis of value added rather than on the basis of their full price.

So far, the maquiladora program seems to have provided long-term jobs. The plants currently employ 25,000 people in Juárez and 10,000 people in El Paso. However, even with an annual payroll of $72 million, the 25,000 employees in Juárez average less than $2500 a year in individual salaries.

In the meantime, the great mass of people who make even less grows more restive every day. Crime, violence, and burglary have increased dramatically, according to local officials, and there is the potential for a major social upheaval. Appropriately, in a city that is named for a revolutionary and that has many streets named for past rebellions, the word most often spray-painted on the public walls is revolución.

Just as the tendency in El Paso is to assign blame for the city’s ills to illegal aliens, the tendency in Juárez is to scapegoat the local chapter of the 23 de Septiembre. An organization with a history of violent acts all over Mexico, the 23 de Septiembre has an estimated 400 members nationwide, but only four “commandos” in Juárez. Although clearly a symptom, rather than a cause, of the city’s problems, the Juárez chapter has done its share of troublemaking. In recent months, for example, members of the group have taken credit for the killings of a Juárez policeman and a plant supervisor at the Sylvania installation in the maquiladora industrial park. Lately, both Mexican and U.S. officials have blamed the 23 de Septiembre for the increase in violence on the border, an accusation that sources close to the group steadfastly deny.

“It’s over-sensationalizing,” said El Paso activist David Morales shortly after the battle at the Black Bridge. “The newspapers said that José Cervantes López was a member of the 23 de Septiembre, but he is not and never has been. Neither are most of the other activists in Juárez.”

The group to which Cervantes and most other Juárez border activists do profess allegiance is the Alianza. Headed by Dr. Vasquez Muñoz, a Marxist physician with two Mercedes and a house in the campestre district, the Alianza claims roughly 150 active members. Unlike the 23 de Septiembre, the Alianza is basically nonviolent in orientation. Its revolutionary activities consist mainly of demonstrating locally for or against specific issues and organizing farm and factory workers. But as the meeting on the Black Bridge showed, the Alianza has developed increasingly close ties to activist groups in El Paso and has taken a strong interest in the plight of people attempting to enter the United States illegally. Asked recently if the Alianza also included organized agitators bent on promoting conflict along the Rio Grande, Dr. Muñoz gave an enigmatic and unsettling answer: “In the pejorative sense, no; in the political sense, yes.”

Through men like Cervantes, a former guerrilla leader, the Alianza maintains at least indirect ties to the country’s land reform movements and to the revolutionaries scattered throughout Mexico. Recent reports from the Mexican interior compare the country to a dormant volcano, and American businessmen with operations deep in the heart of Mexico say they are moving their interests closer and closer to the border in anticipation of some sort of eruption in the not too distant future. Dr. Muñoz, for his part, will only say that he expects something to happen “soon.”

In Mexico, arguments about illegal aliens go back and forth, just as in the U.S. some contend that the continued flow of people to the United States is the last safety valve on a new Mexican revolution. Pointing to INS estimates that at least six million illegal aliens (or roughly 10 per cent of the population of Mexico) are living in the U.S., they reason that this translates into 10 per cent less unemployment and 10 per cent fewer people to feed, house, and clothe. More important, it translates into direct cash benefits. Exactly how much is hard to say, but it is said that one need only look at the Saturday afternoon líneas de viudas—“lines of widows”—that form at post offices in the villages of the interior to receive money from relatives in the U.S. to know that the flow of funds is considerable. According to estimates by several independent and government study groups in the U.S., the annual dollar flow from illegal aliens to relatives in Mexico amounts to between $1.5 and $3 billion per year. This is more than Mexico’s total annual tourist revenue and roughly 10 per cent of the country’s total gross national product.

On the other hand, Dr. Jorge Bustamente, the person recognized as Mexico’s leading expert on illegal alien migration, maintains that the number of illegal aliens living in the U.S. is much smaller and more cyclical than U.S. experts believe. He estimates that there are only about one million now in the U.S. and says that about 85 per cent of these stay only twelve months, while less than 5 per cent stay longer than sixteen months. Bustamente contends that because of the high cost of living in the U.S. and because few aliens earn over $800 per month, they actually send back a relatively small amount of money, more in the neighborhood of $0.5 to $1 billion, rather than the several billions calculated by U.S. experts. Moreover, he says that, despite the relief their absence may offer Mexico’s overburdened social systems, the flow of illegal aliens into the United States costs the country its youngest, most able workers.

Perhaps the only point of agreement is that, for better or for worse, illegal aliens who come to the United States usually do get jobs and usually do make more money than they would in Mexico. As immigration jefe Arturo Castellanos put it, for that reason and that reason alone, “the mojados will always come.”

Leonel Castillo knows why they come as well as anyone in Washington. Although he is a second-generation U.S. citizen born in Victoria, he grew up with scores of wetbacks. His parents, who were also born in Texas, say they are unsure how Grandfather Castillo entered the United States except that “he probably paid someone a nickel to get across.” Now as director of the INS, Castillo must deal with the plight of legal and illegal Mexican immigrants and supervise the activities of their archenemy, the Border Patrol. To a certain extent, his hands are already tied.

“President Carter has instructed me to get control of our border,” Castillo reported in a recent interview. “He feels that we have to do that first.”

An amiable, soft-spoken former city controller from Houston, Castillo does not think that the U.S. can ever completely stop the flow of illegal aliens. However, he does believe that it is possible to reduce the traffic by 75 to 80 per cent. “As best I can determine, that will cost about fifty million dollars per year,” he said. “This figure includes not only enforcing the law on the border, but also policing the international airports ail over the country.”

Although he feels that a plan to tighten the border without a lot of other programs would have a negative effect, Castillo maintained that Carter’s “control first” approach makes “a certain amount of sense.” “I think we’ll see a gradual tightening of the border,” Castillo predicted. “Hopefully, it will be done so that people can enter at official entry points with dignity. We don’t have a system to accommodate even that yet.”

Castillo also pointed out that as head of the INS he inherited a considerable legacy of administrative problems, which, like the border itself, he must get under control as quickly as possible. “We’re still at the basic level of getting computerized,” he said wearily. “We have eighteen million files and they’re still operated manually, if you can believe that. We have no way of knowing, for example, if a student stays in the country after his student visa expires, because it’s too hard to check under the present system.”

At the same time, Castillo said, the Carter administration will continue to consider a variety of ancillary programs aimed at the illegal alien problem. In the past several months, the air has been filled with trial balloons testing various approaches from criminal penalties for employers of illegal aliens to a blanket amnesty for illegal aliens already in the U.S. The latest formulations emerging at the time of the interview included a campaign against the coyotes who smuggle illegal aliens for profit; civil penalties for U.S. employers who hire illegal aliens; and some sort of “nondeportable” status, rather than a blanket amnesty, for illegal aliens now in the U.S.

“There are some serious problems with a blanket amnesty,” Castillo explained. “You have persons from Mexico who have been waiting five years to enter the country legally, persons from the Philippines who have been waiting seven years, and persons from Hong Kong who have been waiting ten years. It would be unfair to them to simply let all the illegal aliens become citizens just because they managed to enter the country without getting caught. The way it looks now, persons who have been living here illegally for less than seven years will probably be given ‘nondeportable’ status. After they have stayed here seven years, they will be allowed to apply for permanent resident status.”

Should this program be enacted, it would avoid two other commonly cited problems connected with blanket amnesty. Illegal aliens would not be eligible for welfare benefits and could not bring other members of their immediate families into the country as they could if simply granted citizenship.

At the same time, Castillo said, the government is considering a “guest worker” program, which would permit Mexican labor to be imported on a temporary, cyclical basis, much as Switzerland and Germany import labor from Italy and Turkey. Though this idea has some similarity to the old bracero program, it is different in that the worker is not tied to a particular employer and would be free to change jobs. “No one wants to talk about braceros,” Castillo said with a chuckle, “but the term ‘guest workers’ seems to be a little more palatable.”

In his short tenure, Castillo has already shown a certain flexibility in this area. In June, he and President Carter got together to permit the admission of 809 Mexican farm workers to help bring in the onion, cantaloupe, and pepper crops in Presidio. Claiming that the crops would rot in the ground unless harvested quickly, Castillo issued an order stating that it would be “tragically wasteful for the nation as a whole, as well as a grievous financial loss for the farmers, if no way can be found to hire workers to harvest the standing crops.” The government arranged for these workers to be paid $2.30 per hour minimum.

But for the near future, most of Castillo’s attention will turn to the monumental task of enforcing the immigration laws. At least some of the border-fencing proposals will likely come to pass. “A fence the entire length of the border is definitely out,” Castillo said. “But I think there will probably be fences constructed in the more heavily populated areas like El Paso and San Diego where essentially people run back and forth between neighborhoods. Those two cities are about fifty per cent of my problem. They have the greatest number of illegal entries and the greatest number of violent incidents.”

The reaction to these proposals in Mexico and El Paso-Juárez has been overwhelmingly negative. “The United States is looking at illegal Mexican migration as if it were simply a domestic problem,” Dr. Bustamente told the New York Times recently. Bustamente predicts that the Carter proposals, taken together, could result in a sort of whip-crack effect. He says that news of an amnesty program, or of the granting of “nondeportable” status, will prompt thousands more to rush to the U.S. in hopes of gaining citizenship. But upon reaching the border, they will be pushed back by a beefed-up Border Patrol or turned away by employers unwilling to hire them for fear of prosecution. As a result, the class of restive unemployed workers already populating Mexican border towns will increase and so will slums, violence, and crime.

Dr. Stoddard’s view is different, but hardly more optimistic. “When the U.S. needs labor, we will bring people in; when we don’t need them anymore, we will send them back,” he said in a recent interview. “It’s just about that simple.” Stoddard says that the recent incidents of violence along the El Paso-Juárez border are merely isolated reactions. He also contends that in carrying out this latest decision to clamp down on illegal aliens, Castillo and the INS will be more flexible and selective in their enforcement policies than many suspect. “My sources tell me that the Border Patrol has already gotten the word from the top not to raid the big farms and ranches in the area,” Stoddard said.

Many of El Paso’s citizens do not seem so assured. They fear that tightening of the border will have much the same effect as hardening of the arteries. The decline in sales suffered by downtown merchants after devaluation of the peso was the latest illustration of the interdependence of El Paso and Juárez, and it comes as little comfort that Castillo predicts the new Carter border policies may have a similar impact on other Texas border cities. More than anything, El Pasoans worry that the net effect will be the creation of a “cactus curtain” along the country’s southern border.

“We don’t want a Berlin wall between our two cities,” says El Paso Mayor Ray Salazar, echoing the sentiments of El Paso citizens, of Mexican immigration jefe Castellanos, and of many others on both sides of the river. “Besides, a seventeen-mile fence won’t keep illegal aliens out. They’ll just go to the end of the fence and come in around it. If the fence runs the entire two thousand miles from Chula Vista to Brownsville, they’ll just cut holes in it. There’s no way a barrier like that can be maintained without spending millions and millions of dollars. And the only result is going to be increased hostilities between neighbors.”

The nature and ramification of any hostilities remain to be seen. But nearly everyone from Leonel Castillo and Ray Russell to Ray Salazar and David Morales agrees on one point: fence or no fence, those who attempt to cross, the border in the future will encounter more resistance than ever before. The battle at Black Bridge and the incidents that have followed it are merely the first skirmishes in what may be a long and costly siege.

- More About:

- Mexico

- Longreads

- Juárez

- Illegal Immigration

- Border Patrol

- El Paso