One Mensan said to another, “I would like you to answer one question for me, a very simple question. What, exactly, is electricity?”

The other Mensan scanned the room with his long, blank, sober face, a face that seemed like some great radar antenna trying to tune in a distant signal. “I would say,” he finally decided, “that electricity is, the, um, the organized movement of electrons.”

“Hmmmm,” the first Mensan said. Perhaps he had meant his question to be more philosophical—there was an amber stone the size of a goose egg hanging from his neck—but he was clearly pleased by this simple, authoritative answer. His eyes gleamed. By golly, it was fun to be intelligent!

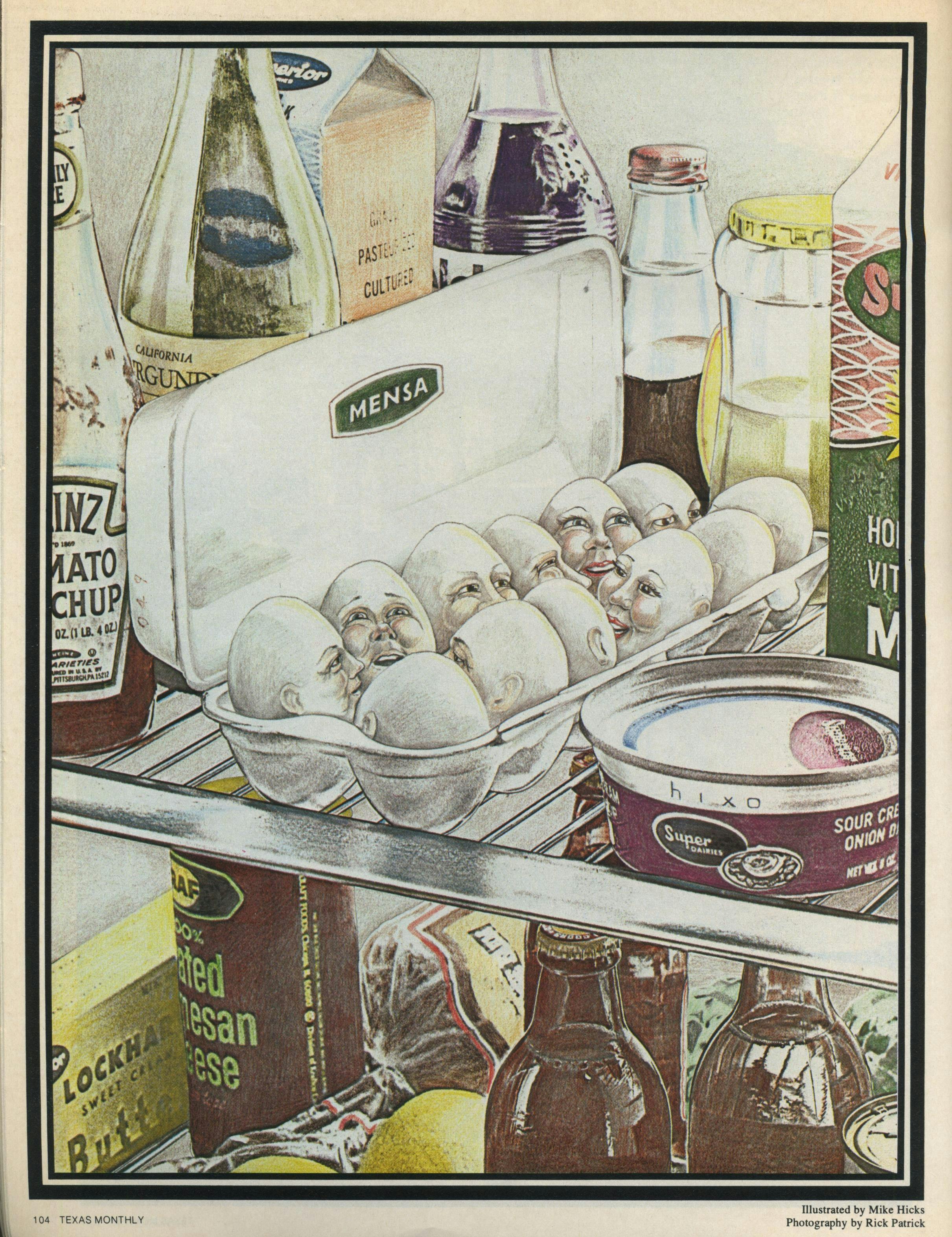

On the day after Thanksgiving over a hundred intelligent persons were milling around various suites on the mezzanine of the Dallas Hilton Inn. They were Mensans—or M’s, as some of the terser members called themselves—and they therefore belonged to Mensa, an organization of people who are smarter than 98 per cent of everybody else. They had come, at their own expense, to a sixteen-state regional gathering.

Intelligence is the only requirement for joining Mensa. Specifically, an applicant must score in the upper two percentile on one of the several dozen IQ and general intelligence tests the organization recognizes. Mensa is a Latin word for “table” (“We are a round table society,” a brochure said, “where no one has special precedence”). Mensa is also a Spanish word for “stupid,” which is merely an unhappy coincidence and not an intelligent decision of the two London barristers who founded the society in 1945.

The organization claims 23,000 active members in fourteen countries, with 150 local groups in the United States alone. According to a Mensa brochure, “Members meet weekly, monthly, yearly, in groups of all sizes, for amusement, pleasure, discussion, education, and to solve problems.” I realized immediately that this was not to be primarily a problem-solving weekend. It seemed to be designed more as a tribal gathering for those Mensans who had been wandering for the past year in the middlebrow wilderness carrying, like acolytes, the delicate vessel of their intelligence.

Here, finally, they could set that burden down. They were among their own kind. Yet Mensa provided for many of them even in the provinces, where the principal learning unit was the Special Interest Group, or SIG. North Texas Mensa, for instance, sponsored SIGs in such things as Drama, Madcaps, Love, Wine Tasting, Passing Fancy, and five different sections of something called Lunch Bunch.

In addition, M’s could get involved with groups who worked with intelligent prisoners or gifted children. There was a Mensa bulletin that advertised Mensa earrings and tie clips, there was a Mensa Education and Research Foundation (MERF) that awarded grants and published the Mensa Research Journal, which included articles like “Universal Symbolism of the Salamander and Basilisk” with footnotes like “1 Newt an ewt, eft M.E. evete<A.S. efeta, ‘lizard.’ Cf. Egyptian: fent, ‘a worm’ and Greek ips, ‘worm,’ ophis, ‘snake.’ Cf. also ‘wet,’ ‘water,’ etc.”

I had never learned my IQ—that sort of information was classified in every school I attended—but since I did score “above average” once when I left only two golf tees on a peg game I found on a restaurant table, I was confident that I would blend in. I had come to Dallas dressed the way I imagined intelligent people would dress—sort of tweedy—and I had already had a chance to study my Mensa registration packet. In this packet was a little red comb, the purpose of which I never discovered, and a sheet of paper with mimeographed questions for the Mensans to answer. “Your house is burning down (up?). No living things are in it. Which three possessions would you save?” “If your mate were an animal other than man/woman, what animal would he/she be?”

“Okay, Dollinks,” it said at the bottom of the page, “now take this cogently completed questionnaire and stuff it (no, not in your oubliette) in the Mensa Questionnaire Box . . .” Wandering about the little meeting room where, according to the program, “conviviality will abound,” I noticed no common denominator other than the intelligence implied by the Mensans’ simple presence. I suppose I had been expecting a meeting of some solemn federation of people whose brows were as deeply furrowed as their brains and who sat around doddering under the sheer weight of their own brilliance. But the group was surprisingly diverse. A small cluster of people had gathered around the piano the way it’s done in beer commercials, and they were swaying back and forth while a man dressed entirely in black polished off the “Prélude á l’apres- midi d’un faune” and segued into “Chopsticks.”

“It’s just like any other organization,” a Dallas librarian explained. “You have the same cross section of nice people, bastards, and screwballs.”

“It’s an organization that seems rather purposeless to some people,” a woman named Ann Patrick Cook told me. She was a national officer in Mensa. As she spoke her voice kept slipping into an ironic register. “Yet it serves a purpose in these people’s lives who have gone to a lot of trouble and expense to meet others. Generally speaking, for instance, my neighbors and co-workers only like to talk to me about blow-by-blow descriptions of ballgames and their latest surgery. I don’t feel I should have to apologize about having some thoughts beyond what the local ball club is doing.”

She went on to tell me about the various tests a prospective Mensan could take to gain membership. They included the GRE and the Army General Classification Test, and when translated into an IQ score, the admittance requirements averaged out to about 130. She said that on occasion Mensa has made provisions for people whose intelligence does not register on conventional tests. “There’s no economic, social, or philosophical bias. My son here joined at age six.” She pointed to a boy sitting at our table who seemed to be staring off into space.

“There is only one thing that distinguishes this group,” said Rod Vickers, who had joined us. “They are one in their diversity.”

Vickers was an industrial equipment engineer from Shawnee Mission, Kansas. In his mid-forties, he had a cultivated physical radiance. I did not think it was a coincidence that his eyes matched exactly the shade of his blue turtleneck: they seemed to be accessories, like cuff links. He kept swirling his drink and grinning down into the glass, as if he had something trapped in it. Having heard that Vickers was scheduled to conduct a seminar the next day, I asked him what it was about.

“Oh, I’ll be giving a little eclectic,” he said, “a little eclectic on human behavior.” He took a pretzel from a bowl on the table and scraped off the salt into an ashtray as he outlined for me his “eclectic metatheory.” (The Mensa program had dubbed him the Eclectic Rod.)

“We have within our present capabilities the ability to understand the impetus for life itself, the methodology to guide us to the highest potential. The great humanitarian psychologist Masslow was a generation ahead when he said, ‘The fully actualized human being is attainable!’ ”

“Hmmmm…”

“We need to better utilize our neural skills, those which coincide with the upper hominid at the best stage of maturation.”

When Vickers had finished explaining his metatheory, I strolled over to the game room Mensa had set up on the other side of the mezzanine. It was obvious to me by now, since almost all the people I had met were psychologists or engineers or data programmers, that the average M’s intelligence was of the analytical variety. Here in the game room that impression crystallized. Here was the hard core. Young men with wiry beards and hair that looked like it had been cut by an electric fan sat around smoking pipes the size of hookahs. Pretty college girls with rheumy eyes squinted about the room in search of someone to play Battleship with. Sixty-year-old women were assembling psychedelic starburst jigsaw puzzles.

There was some cocktail party chatter emanating from the people who had wandered over from the cash bar in their tailored leisure suits to observe the game playing, but all was solemn down on the Wff’n Proof and Clue boards. A naked, humorless, intellectual power pervaded the room so entirely I began to feel myself developing a headache.

All the games were traditional and store-bought except for an IBM typewriter hooked up to a computer that used it as the medium for its chess moves.

“One thing you have to remember about this computer,” someone warned a man sitting down to play. “It’ll do anything to keep from losing a man. It just can’t stand that.”

“Welcome to the best part of the world,” Judge Fite greeted me. Judge Fite was not a judge—that was simply his first name—but he had such a patriarchal bearing he could have easily passed for a Supreme Court justice. He was a realtor—“a capitalistic land conservationist”—who insisted that his employees take “one hour Idea Time each day” and “meet three strangers and make three friends every day.” He was serving as master of ceremonies for the weekend and had been in Mensa since 1954. “I didn’t have the advantage of a college education, so I involved myself with various Mensa courses. You get a pretty good exchange of ideas from these people. They get involved in so many things because they’re mind people.” Judge Fite said that in his spare time he liked to enter exotic art competitions (“copper wire on plywood, things like that”) and to take apart and put together puzzles. “I’m a puzzle man. People send me puzzles from all over the world. I got one not too long ago called the Merlin Stone. A series of interlocking pieces of wood. Did it in three seconds. One I had a year before took me three months.”

I met an engineer from Arlington who was hovering over the game boards looking like he wanted to be invited to play. He was in his twenties and wore a shapeless black suit that seemed as if it hadn’t ventured out of his closet since high school.

“I’ve met people from various facets of the social strata,” he said. “I’m interested in electronics, games, conversation. I enjoy listening to good discussions. I can relate to the difference between Mensa groups and non-Mensa groups, such as fraternal, square dance, and the like.”

He did not see people as often as he liked because he worked nights, and his friends were “preoccupied with family and trivial matters of the day.”

“I get rid of trivial matters in a hurry,” he said. “I put them in any time sequence I deem necessary or that they’re operable in.”

Back in the conviviality room things were winding down. There was some talk about orgies. “I would have loved to come to Kansas City when you had your orgy but I just couldn’t make it,” a middle-aged woman in pigtails told a man slumped in a chair. Another woman was making her way through the room informing M’s that there was to be an orgy tonight in room 365. She didn’t go out of her way to invite me, but I reflected that I could use my press card if necessary.

“What is all this orgy business?” I asked the Eclectic Rod.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” he said, “we Mensans talk a great orgy.”

The second day of the convention, a Saturday, was so densely scheduled with seminars and discussions I was afraid my unproven intelligence might not be able to take it. In the morning I dropped in on a seminar called “Reincarnation or Once is Not Enough.” The little meeting room was barely half full, and the audience was almost entirely women.

The seminar was conducted by a husband-and-wife team—the founders of a metaphysical research institute in Dallas. They were both large and stout and had that leaden serenity of occultists. Standing together at the podium, they reminded me of the kind of people whose houses children avoid at Halloween.

“We do not believe in reincarnation,” the husband said. “We know we reincarnate. There is a big difference between believing and knowing.” The audience seemed to nod almost on cue. “The question is—somewhat—why did you choose to be what you are today? Now my wife Lois has the capacity of going to God’s records, and going to His records it is possible to re-create in toto everything that has always happened since the time of creation. Everything. Including the secrets.”

His wife then talked about some of her case histories. “People who have allergies today, many of these are recalls from previous existences. I have helped many, many people overcome their allergies. There was one woman I helped who had one foot smaller than the other and also a fear of cats. In going back we found a lifetime in China, where her uncle tried to take her real estate by frightening her and driving her out of her mind. He would terrify her with cats, you see. Well, she has overcome her fear of cats, but in this lifetime she will have to continue to buy her shoes in two different sizes. We have, however, put her in touch with some people whose right feet are larger so they can trade off shoes with her.” She went on to talk about guardian angels, karma, Jesus Christ, the extraterrestrial origins of marijuana, and the clothes that beings from other planets wear (“kind of like skin suits”). “All of this comes together in the realm of many different things,” she said.

Oh boy, M’s, I thought, let her have it. I had read in the Mensa brochure that at a Mensa gathering no statement went unchallenged, and I was ready for a pitched battle. But the only people in the room who wanted to talk were interested in setting up appointments to explore their previous existences and in discussing the otherworldly writing techniques of Taylor Caldwell.

“An Eclectic Approach to the Enhancement of the Human Condition and the Realization of Human Potential” was the full title of Rod Vickers’ seminar. He had written this on the blackboard and I noticed that several people in the room besides me were writing it down in notebooks.

“I am going to bring you a grand, glorious revelation detailing the path to perfection,” Vickers said. Somehow the revelation slipped by me, but the lecture itself was rambling and good-natured and boring in a way that nobody seemed to mind. It touched on self-hypnosis, electroshock, insanity, and depression.

“I was twenty-nine when I got divorced,” a woman said during the discussions afterward, “I was deeply depressed. I had to find something and thank God I found Mensa.”

All day the idea of Mensa had been striking me as rather creepy—it seemed to me that the moment intelligence was perceived as a static measurable quality it was no longer intelligence at all. But I saw now how irrelevant such a judgment was in this place, how little it took into account. Here were people whose intelligence had been less a blessing than an invisible force that kept them at a remove from the social mainstream. No wonder they were proud of their IQ tests: it was as if those tests had diagnosed a strange syndrome, a syndrome that made it possible for them to enter an exclusive sanitarium in which they would be coddled and appreciated and where their intellectual loneliness would be assuaged.

At lunch an electrical engineer who was sitting next to me pried up with his fork a layer of broccoli and limp hollandaise sauce. Underneath the broccoli there was a slice of ham.

“Hmmmmm,” the engineer said.

We discussed whether or not software was patentable and whether either agnosticism or cryogenics was the answer to anything. After everyone had finished eating, Judge Rite rose up at the banquet table and introduced Dr. Michael S. Brown, who spoke on “Genetic Variation in Human Potential” as he projected slides of dense chromosome maps and double helixes. I didn’t understand a word of it, and neither did a few M’s I talked to afterward, who had hoped that the lecture would have provided practical advice on how to raise a bumper crop of quiz kids.

After lunch I attended a seminar called “Hypnosis and Parapsychology,” in which “well-known psychiatrist about town” James A. Hall conducted what I thought was a very lucid and fascinating discussion.

“You’re saying in effect that hypnosis has to be ancillary modality,” a young man with a tape recorder asked.

“Precisely.”

Next there was a lecture on graphology given by Jay Larsen, whose shaven head was set into the folds of his white turtleneck like an egg in an eggcup. Larsen said he had been analyzing handwriting for ten years. At present he worked as a graphology consultant for various firms. While he spoke, his wife passed out flyers for their “Dare to Be Aware” establishment. The flyers advertised “Crystal Ball, Cosmetics, Astrology, I Ching, Gift Certificates.” “Handwriting analysis,” Larsen said, “has been going on ever since the days of Freud and Mesmer. We can analyze the handwriting of any person as long as they’re using the Greek alphabet.” The audience, which was sizable, graciously let this slip pass. Larsen handed out pieces of paper on which we were instructed to write our names and incidental information. When Larsen had gathered these up he proceeded to analyze a few of them at random.

“You show to be an outgoing person with lots of energy,” he told one woman. “You have good concentration ability.”

“What characteristics in my writing do you look for to determine that?” she asked.

“Oh, some characteristics.”

To someone else he said, “You have a good mental antenna. You seem to be intelligent.” Then he grinned sheepishly. “Well, that goes without saying.”

“Are you aware of the pattern on the table?” a woman asked me at dinner.

I took a closer look at the table. Four swaths of cowboy bandana material intersected at its center, and from this spot there sprouted strands of barbed wire and yellow roses. “The yellow rose of Texas,” she explained. “I’m in charge of the decorations. I worked all afternoon on them so you’d better appreciate it.”

Her name was Rosemary Hickey. She was somewhere on the far side of middle age and had a natural vibrancy that seemed to be in the process of fermenting into eccentricity. In Plano, where she lived, she did what she called “people counseling” in her home. She told me she was considering writing a science-fiction story about “intergalactic marriage counseling.”

We were convened at the Grand Banquet, the main event of the three-day conference. Some of the ladies were slinking about in evening gowns, though there was obviously no dress code. I noticed one woman wearing a shapeless purple blouse on which Sex Sex Sex was written in green letters.

After dinner Judge Fite windily introduced Dr. Harvey Davisson, a Dallas psychologist who looked like Charles Darwin and seemed nervous whenever he faced the audience, as if that collective front of intelligence might turn hostile at any moment. He spoke about a “biochemical shield” that dammed up the natural discharge of anxiety and trauma and implied that the way to break through this shield was to reexperience the pain that had caused it. He asked for a volunteer so that he could demonstrate. A graduate-student type promptly offered his services and was instructed to lie down on the floor.

“Now, are you aware of any tension anywhere?”

“Well, I guess my shoulder’s a little tense.”

“Would you move into that pain, focus on it? Feel free to moan.” The psychologist held the portable microphone close to the subject’s mouth.

“Owwww,” the subject said, rubbing his shoulder and giggling a little. “Owwww, that really hurts!”

“Let your body move with the pain. Let yourself be aware of any memories as you move with the pain.”

I could not help admiring the guy. He was giving it all he had. But just when it seemed he was about to break through to the pain he had been carrying within him all these years a bossa nova version of “Guantanamero” erupted from a wedding reception in an adjoining ballroom. Nevertheless, the subject plowed through the distraction and let out a reasonable scream.

“My hunch is you may get a lot of relief if you stay with the screaming,” the psychologist said. The band in the next room began to play “Feelings.” Some of the Mensans, who had until now been standing around in a semicircle, looking down at the subject on the floor, began to filter out of the room. A few of the women wearing gowns seemed to want to dance.

The subject let out a bloodcurdling scream and drew up his legs and kicked at the air.

“Just express what you need to express,” the psychologist said.

Feeeelings, oh—wo—wo feeeeeeelings . . .

“It’s no use. I just feel silly.”

He was still on the floor trying to feel his pain so he could get rid of it when I left the ballroom and wandered down to a party in one of the suites. There I met Jim and Susan Wantland, a married couple from El Paso who were both Mensans and had met at a Mensa function.

“Out of every one hundred Mensans, maybe three couples are both members,” Jim Wantland said, “and usually you’d find that two of those couples met at a Mensa meeting.” I asked him what happened to people whose spouses were M’s but who were unable to qualify themselves. “Well, I think if you’re smart enough to marry a smart person you should be given full recognition by Mensa but not necessarily full membership.”

Susan Wantland was something of a prodigy. She graduated from college at eighteen and received her master’s degree by the time she was twenty. “I mean I was in the third grade at six, ” she said. “It got so it was sort of spooky around my parents—my father only had an eighth-grade education. When you’re an eleven-year-old high school student the guys are not too eager to take you out, so this kind of thing is really welcome. A lot of people have the idea that Mensa is a bunch of geniuses, but this is one place I feel the opposite. You can leave your IQ at the door and be yourself.”

“The people who join Mensa and come to the meetings,” her husband said, “are people who don’t get conversation in their families. Here you can converse quickly and people will understand you quickly.”

“You can use a three- or four-syllable word and not feel defensive about it,” Susan Wantland said.

I wandered about and met a few more engineers and a secretary and a maid.

“Among our twenty thousand members at least a dozen are hit men for the Mafia,” someone told me. “Statistically, this has got to be true. I know for a fact there are two witches in Mensa.”

“Have you been plied with drink?” Joan Kollar, who seemed to be the hostess, asked me. “I’ll never forgive myself if you haven’t been plied with drink.”

Down the hall Jim Fredd, “the diabolical Jim Fredd,” was passing out copies of his trivia test to all interested parties. I consider myself fairly good at trivia (I know almost all the lyrics to “I Married Joan”), so I decided to give it a try.

“I deliberately set this one up so it’d be one rough bugger,” Fredd said. “Ain’t nobody got a positive score yet.”

I scanned the questions. “Who was Frederick Fleet?” “You have just decided to split a Nebuchadnezzar of Monopole champagne with a warm, close, personal friend. How much will each of you get if you share it equally?”

“This is impossible,” I said. “I give up.”

“You can’t do that. That would give you a zero and make you the winner. You have to guess wrong and get a negative score and then you can give up.”

I guessed that the snake with a fang length of 1.96 inches was a bushmaster. It was a Gaboon viper. I got a minus one and was comfortably out of the running.

“I enjoy being with intelligent people,” Jim Fredd said when I asked him why he had joined Mensa. “It’s been marvelous.” He was modest about his trivia talents. “In a weird contest in this group I think I could hold my own,” he said, with an absurdist glint in his eye. He reminded me of a classmate I once had who had set up a little laboratory and devoted probably years of his life perfecting the stink bomb.

Fredd told me about an independent nation he used to belong to called Mermannstadt. Every few weeks Mensans belonging to this nation or to others incorporated under the Centre for Creative Anachronism would dress up in homemade suits of chain mail (Fredd had a helmet made out of an empty Freon can) and fight each other with swords in the park.

“This was before the lord of the realm went wacko,” he said.

On Sunday morning the Mensans put on a show. They did not put on Coriolanus or The Trojan Women but something called The Terrible Tracks of Trauma or M Is for the Mother Who Mislaid You. It was, of course, written and performed by M’s and though purported to be a parody of a melodrama it never really transcended the genre. There was a lamebrain hero with spangles in his hair (Jim Fredd, daringly cast against type), a hissing villain in a black cape, a case of mistaken identity, and a Little Nell who at final curtain is sexually liberated and runs off to open an “adult arcade” with her inheritance. It was cleverly written, well staged, fairly well acted, but all these elements served to make it seem only more peculiar.

“Encore! Encore!” Judge Fite called. Then we all paraded into the banquet room again. A speaker was scheduled to address us on “Laser Magic” but he called to say his wife was in labor and he couldn’t come. Rod Vickers was pressed into service to deliver his eclectic again.

“I am going to bring you a grand, glorious revelation detailing the path to perfection,” he said.

At the end of the program Judge Fite read a piece of inspirational doggerel called “What It Means to Be an American.”

“I would like to leave you with a thought from Dewey,” he went on to say. “ ‘The greatest of all life’s endeavors and the only occupation worthy of continuous pursuit is the search for the frontiers of one’s own personal potential.’ With that I judge that this convention has reached its finality.”

The Mensan next to me, the one who had known the definition of electricity, was still eating his brunch. I watched him as he sliced his cantaloupe into twelve exact pieces and dredged the whole thing with pepper. Next to him a man was filling out his questionnaire. When he came to question 10, “The Ideal Mensan is One Who ________________,” he seemed to think a long time before leaving it unanswered and stuffing the questionnaire into his oubliette.

- More About:

- Longreads