“George, you’ve got no base here. All you’ve got is a famous name.” This time, George W. Bush listened when Texas political operatives like his longtime friend Jim Francis warned him about running for office. It was early 1989, and ever since the previous Thanksgiving, the president-elect’s son had been discussing with friends the 1990 gubernatorial race. He’d now distinguished himself on a national stage as his father’s gatekeeper, his speech-making surrogate, and, when the press disparaged Dad, his avenging angel. Lee Atwater had made some calls to Texas kingmakers on George W.’s behalf. Among those who believed the son could prevail in a contested Republican primary and then slay the dreaded Ann Richards was another Atwater protégé, Austin direct-mail specialist Karl Rove.

But if Rove was wrong, George W. would end up defeated, probably broke, publicly ridiculed as a man whose only achievement was to be born a Bush.

Instead, he moved to Dallas and bought a baseball club.

As stairways to a governorship go, George W.’s was as original, if not quite as cinematic, as Teddy Roosevelt’s abandoning a life of letters and bureaucratic appointments to lead the Rough Riders up San Juan Hill. Seeing the Bush name as instant credibility, baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth gave the imperial wink to the group George W. began assembling to buy the Texas Rangers in April of 1989. Of the $86 million asking price, George W. himself could pony up only $606,302 —the subject of much smirking in some circles—but the Rangers group was hardly hurting for money. What it needed was a managing general partner who could generate some local excitement about this sad-sack American League franchise.

Beginning with that first season in 1989, George W. planted himself in Arlington Stadium—not up in the air-conditioned VIP suite where Laura and the twins occasionally sat but right behind the home-team dugout, adjacent to first base. He made it a point to sit through all nine innings, no matter the score, no matter how brutal the summer heat. He sat there sweating right through the short-sleeved dress shirts that Laura had helpfully bought him, scarfing down peanuts and hot dogs, autographing literally thousands of his own personalized baseball cards for fans who lined up hoping for a moment with Pudge Rodriguez or Pete Incaviglia but settling for the signature of a president’s son.

The way George W. saw it, this wasn’t small ball. He was changing the culture of baseball in the Dallas—Fort Worth Metroplex. A new stadium was in the works. And speeches—he’d darken every Rotary Club’s door in the region, always talking about the family experience and building traditions, and it didn’t seem to matter how larded with hokum it was; ticket sales always shot up after the managing general partner ran the circuit. What other baseball owner did this sort of thing?

To other tasks as baseball exec, George W. was less suited. He could barely sit still during the lengthy stadium construction meetings, and he left the tough personnel decisions to others. (This included the infamous Sammy Sosa trade to Chicago, though at the time neither Bush nor anyone else in the Rangers organization thought that manager Bobby Valentine was dealing away a home run king.) His preferential treatment of the great Nolan Ryan—excusing the 42-year-old pitcher from certain road trips, letting Nolan’s boys romp around in the clubhouse—rankled a few teammates. Now and again he made untoward comments to the press, such as when he predicted that the Rangers would win the pennant in 1992 or when he expressed an interest in Boston Red Sox pitcher Roger Clemens, leading Boston’s front office to accuse him of tampering.

In some ways, the job was an invitation to regress. He could hang out in the cafeteria jawing with the veteran scouts about the lineup of the 1962 Pittsburgh Pirates. He could stride into the visiting announcers’ booth and have a snicker with Bob Uecker or Phil Rizzuto. He could fill shelf after shelf in his office with baseballs autographed by the game’s legends. He could play cards with the manager. He could spend weeks touring the nation’s great ballparks for “research.” He could let the twins play whatever music they wanted over the stadium loudspeakers. He could wear cowboy boots garishly bearing the Rangers logo and not be viewed as pathetic.

He could do all this and get filthy rich, his $606,302 total investment ballooning into a sellout check for $14.9 million less than a decade later.

But apart from what he could do, did he really know what he was made of, deep down?

Not yet.

The humiliation of his father’s defeat by Bill Clinton in 1992 had only begun to subside when George W. told Rove, “The great irony is, Dad’s defeat makes it possible for me to consider running.”

He needed a reason, of course. It wasn’t enough to simply take down Ann Richards, the helmet-haired dragon lady who had sucker punched his father—really, the whole Bush family—with her acid quip at the 1988 Democratic National Convention: “Poor George. He can’t help it. He was born with a silver foot in his mouth.” Then one day, George W. was driving around Dallas, listening to the radio, when he heard Richards say she frankly had no idea how to solve the mess that the Texas school financing system had become. He had his reason. “I can’t believe a governor would say, ‘I don’t know what to do’!” was his sputtering refrain thereafter.

He summoned to his office a Democrat and Dallas school board trustee named Sandy Kress. When told by Kress that he wouldn’t endorse a Republican, George W. replied, “I didn’t ask you here to back me. I want to know these things.” And George W. read from a notepad containing his scribbled lines of inquiry: How do we hold schools accountable? What difference does money make? Who are the best experts?

He summoned as well a Dallas County judge named Hal Gaither. “Teach me about juvenile law,” George W. said. “I’ll make the time.” When asked by the judge why a baseball owner would care to know about determinate sentencing and recidivism rates, George W. replied evenly, “Because I’m going to be the next governor of Texas.”

He showed up at Rove’s shabby Austin office to meet with Marvin Olasky, the author of The Tragedy of American Compassion, which in two years Newt Gingrich would hail as the single best case made for welfare reform, but which Rove, being Rove, had already digested. George W. pelted Olasky with questions—not the usual how-do-we-cut-the-welfare-rolls dreariness: He’d been thinking all this through, way outside the box, dispensing with small ball. “How can we reform welfare to help people?”

To these three key issues—education reform, juvenile justice reform, and welfare reform—Rove added a fourth: tort reform. For years, Bush’s stunning 53—46 victory over the mighty Richards would be seen by some as a referendum on Clinton, part of the Newt Gingrich tidal wave that washed away scores of Democrats great and small. Mainly, though, it would be hailed as a triumph of ferocious discipline—the challenger inseparable from those four issues, his “Roman candle” temper never once igniting as he waded obliviously through the rivers of kerosene Governor Richards poured with her incessant references to “Shrub” and other Molly Ivins inspirations. It would be remembered for Rove’s crafty incursion into the yellow-dog-Democrat territory of East Texas, where allegiances were wobbly to Hollywood Ann, what with her alleged posse of lesbians and her rumored druggie past.

Unremembered would be the Bush campaign’s missteps—so many of them early on that Francis and Rove sacked nearly the entire staff in the spring of 1994, bringing in the burly Joe Allbaugh from Oklahoma and a former TV reporter and state Republican party director named Karen Hughes to right the foundering vessel. Forgotten as well were the clunky early speeches Rove wrote for George W. and the latter’s tendency to bark out alarming declarations on the stump like “I am a capitalist!” before Message Dominatrix Hughes curbed his tongue.

For all the Rove/Hughes/Allbaugh Iron Triangle’s shrewdness, the Bush campaign was far from seasoned. Its policy director, Vance McMahan, had not worked a day in politics or government. Hughes herself had no experience in a campaign, Allbaugh none in Texas. And the man on whom George W. would most frequently rely for clarifying issue sticking points—and for delving into his past so as to anticipate questions about his bachelor days and his service in the National Guard—would be a 23-year-old University of Texas graduate named Dan Bartlett who happened to be the only one in the office when the candidate would call at seven in the morning, asking, “It says general crime’s gone up in Brazos County by thirty-six percent, but how do we know that?”

This first Bush Machine was more akin to a children’s crusade, and Richards had ample opportunity to squash it. But the governor preferred her exquisite put-downs to an engaged campaign. For months she paid her opponent no heed while he laid out the four defining issues. (But only those four; George W. had no life experience in matters such as health care, and it did not occur to the Richards camp to expose his ignorance early on.) For the same period, she spent little from her huge, Hollywood-endowed war chest when she could have forced the Bush camp to drain its lesser coffers. And Richards assumed that areas of Texas in which Republicans from time immemorial had been gaily tarred and feathered did not require her attention. She had forgotten one of her favorite aphorisms, that 80 percent of life is just showing up. That formula seldom holds true in politics, but it did in Texas in 1994: George W. showed up, Richards did not, and that made 80 percent of the difference.

From that moment on, he was a star. And he seemed properly fit for stardom the very next day after his election, when he stood in the Austin Hyatt and faced the national media with aplomb and grace. Before being sworn in, he responded to California’s enactment of Proposition 187—denying benefits such as public schooling to illegal aliens—with the stirring promise, “In Texas, we’re gonna educate the children.”

But there was a bit of swagger to that declaration as well, a hint that George W. Bush had arrived somewhat unready for the realities facing a state’s chief executive. And indeed, at an event for Republican governors in Williamsburg, Virginia, shortly after his election, he came off to some as a good-time Charlie rather than someone of gubernatorial stature.

But among George W.’s lifelong attributes was his awareness of his own limits and the willingness to surround himself with able (and loyal!) experts. The very first of these, after winning the election, was his tailor.

He knew that he was an awful dresser—had to know, the many times it had been pointed out to him: first in Midland, where a golf tournament offered a George W. Bush Dress Award to the worst-dressed participant, and later in Dallas, where his Rangers co-owner, Rusty Rose, would mercilessly observe, “Gee, didn’t you wear that shirt yesterday, George?” It never really bothered him much. Comfort was all-important, whereas fashion, pretty much by definition, was the province of those who felt insufficiently comfortable with themselves. Of course, Laura was comfortable and at the same time immaculately turned out. Bless her heart, she had given up the fight on George W.’s wardrobe long ago.

Now, however, he was on a stage where such things mattered. “It’s part of the discipline,” Jim Francis would say. And so one day Francis called tailor Barry Smith, who arrived at George W.’s Dallas home on Northwood just after the 1994 election.

Knowing it was time for a proper schooling, George W. listened. “I know you don’t like clothes—I can tell that,” began Smith. The governor-elect did not take umbrage, so he continued: “But we need to figure out what’s going to work well for you, because you’re entering a public profile. So, three things we need to think about. One, what is what you’re wearing going to look like on camera? Two, what are your best colors? And three, what do you like?”

“Well, obviously, I need dark suits,” George W. said. “I don’t do a lot of patterns.”

“Then let’s stick to basic blues and grays, get you inaugurated, and we’ll go from there.”

They stood in his walk-in closet and appraised his current wardrobe. It was a horror show. The tailor fingered the polyester Haggar slacks with the elastic waistband (the Haggar family were friends of George W.’s) and said, “I don’t think these portray the right kind of image you’re looking for.”

“I like them. I don’t much care for belts.”

“But they don’t take you to the next level. I’m not saying you have to throw them away. Wear them around the house if you want.”

Drawing the line, the governor-elect said, “I don’t like cuffs. They always get caught on something.” Smith assured him that he could do cuffless trousers.

Footwear: boots. A couple of pairs of loafers (which once had tassels, but he had cut them off), several pairs of running shoes, but otherwise, boots. He would be wearing them with his suits. Case closed.

They moved on to his dress shirts, which were all white—or had been at one time. “These have seen better days,” George W. chuckled as he noted the yellow rings under the arms.

They looked at his suits. A couple of them, purchased at a Dallas haberdashery, were quite nice. But George W. didn’t like them. “These jackets, they’re grabbing me,” he said. “So I’m just not gonna wear ’em.”

Smith suggested that they take all of his suits out of the closet. In one pile they would place the suits to be retained. The other pile would be donated to his church. In the end, the church made out like a bandit. Two suits were culled from the junk—uncomfortable ones, but they cost so damned much it seemed a pity to just toss them out.

It was done. Having already achieved success, George W. Bush would now begin dressing for it. And fevered from the breakthrough, he went a little crazy that afternoon, also ordering from Smith several pairs of socks, belts, ties, shirts, sport coats, and even a couple of basic lace-up cap-toe shoes.

But he kept some of the Haggar slacks with elastic waistbands. So comfortable!

He would succeed as governor because he wanted to get big things done and refused to allow the legislative process to water down his big things into little things. He would succeed because he would capitalize on Ann Richards’s alienation of her own tribe and befriend several Democratic legislators, inviting them to cookouts at the Governor’s Mansion and UT basketball games. He would succeed because he thought to bring in conservative big thinkers like James Q. Wilson and Michael Horowitz to push him and his staff with heady queries: What changes behavior? What is the government’s role in bringing hope to its citizens? How do we break the cycle of despair?

And so, in that historic first legislative session of 1995, Bush, Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock, and Speaker Pete Laney succeeded in passing the full monty: tougher juvenile justice laws, greater accountability in education, tighter restrictions on welfare, and civil suit reform. True, the first three initiatives had been moving through the legislative pipeline prior to Bush’s arrival, but the fact remained that George W. Bush campaigned to accomplish four things, and he had made good on his promise. Rove divined in this a strong whiff of national electability.

Bush imposed on the governor’s office a style of management that was not quite strict and not quite casual. By 7:45 in the morning he was in his office, signing letters, working his way down the call list. His subordinates knew to be in earlier (and never to be late) but also knew that the governor’s door was open; they didn’t have to grovel for face time.

They knew as well that the governor preferred his meetings short. “Give them an hour, they’ll take an hour,” he would say. “Give ’em ten minutes, they’ll focus better.” They knew that it was best not to bring him the heavier policy stuff right after lunchtime, when he would have just returned from a jog under the boiling sun. They knew that he could be quite impatient and peevish but that unpleasantness did not fester in him. “Well, don’t you think you ought to know that sort of thing from now on?” he would say to the blunderer in question. And after eliciting the correct reply, the governor would move on.

Though he was now quite the public figure, it was hardly a confining thing. He could shop for his own running shoes and jog his six miles on the hike-and-bike trail. As with everywhere else he went, George W. transformed the governor’s office into his own personal frat house, bestowing nicknames like Prophet (Hughes) and Pinkie (Allbaugh) and Turd Blossom (Rove) and Hawk (legislative director Albert Hawkins).

Still, was the job big enough?

Could he be of greater consequence?

On the early afternoon of February 18, 1998, Bush and Hughes arrived at a juvenile prison in Marlin. Because the governor was running that year for reelection—and after that, who could say?—Hughes had arranged for the local and national press to attend. This was an extraordinary situation, since the identities of criminal youths were protected by state laws. But the photo op of Governor Bush dispensing tough (but compassionate!) love to his young wards was irresistible, and Hughes wanted it out there in the public domain. So the youth prison officials painstakingly obtained signed waivers from the parents of 22 juveniles, half of whom now sat in their orange jumpsuits beside Hughes’s boss. While the TV cameras rolled, one boy after the next recited his own litany of criminality—I’m Jimmy, I’m from Mineral Springs, at the age of thirteen I did steal the next-door neighbor’s car and I did run over my grandma with it, which did cripple her permanently—followed by his acknowledgment that he, rather than society, was to blame and his pledge to do better.

This was the Responsibility Era personified, as Bush well knew. It was also exploitative, and he knew that as well. This prefab moment was about winning votes by broadcasting images of a human transaction that never was. And so it was with an odd mixture of relish and embarrassment and finally impatience that he sat there, fidgeting a bit as the dreary testimonials proceeded. At 1:15 he had to be out of there. Other photo ops and glad-handings awaited in Terrell, Kaufman, Greenville, Richardson, and Garland, before the governor’s private plane would at last angle back south toward Austin.

A scrawny fifteen-year-old black kid raised his hand.

“Can I ask the governor a question?” said the boy, a petty thief from Tyler named Johnny Demon Baulkmon.

The juvenile officials blanched. Johnny had crossed a forbidden line, for which he would be punished later. But nothing could be done about it now.

That familiar jagged half-smile appeared on the governor’s face. “Sure you can,” he said.

“What do you think about us now?”

Bush fumbled with his fingers. He had no speech at the ready. No bubble to protect him. The cameras brought here to facilitate his photo op now bore down on George W. Bush, the most powerful man in Texas, at strange parity with a black juvenile delinquent. Only fifteen days ago, he had passed on the chance to grant a stay of execution to internationally renowned ax murderer and born-again Christian Karla Faye Tucker. “I have concluded judgments about the heart and soul of an individual on death row are best left to a higher authority,” the governor had said in the prepared statement that sealed her fate. Nothing in it reflected the anguish that had compelled him to clear his entire calendar on the date of Tucker’s execution. That was the way it was. A leader had to be impersonal at times. He had to keep it in. Had to be . . . a policy personified. But right now, staring at Johnny Baulkmon, Bush could feel that he was about to cry.

His words, when he at last found them, sounded almost confessional: “You look like kids I see every day. And I’m impressed by the way you’re handling yourselves here. I think you can succeed. The state of Texas still loves you all. We haven’t given up on you. But we love you enough to punish you when you break the law.”

That was the answer to the question.

A strange euphoria overtook Bush and the other adults in the dormitory. Something had just taken place here that did not ordinarily occur, either in youth prisons or on the campaign trail. A sense of institutions humanized, of possibility. The Texas Youth Commission officials hugged and high-fived each other when the governor departed. But it was Bush who could not get over the encounter. For weeks thereafter, he recounted it to aides and friends the way other men might rhapsodize about a fishing tale or a chance bar stool flirtation with Sharon Stone.

Except that it was not myth. It was not braggadocio. It was anything but trivial. No: It was Big Picture collapsed into a singular, frail human moment. It was the Responsibility Era, Compassionate Conservatism—it was why he was in this. And when Bush was this seized by inspiration, the ever-attuned Hughes knew what to do next. There had been a similar moment four years ago, when her boss first ran for governor—a welfare mom he’d met in Dallas, or something like that, she couldn’t remember—and afterward Hughes had made it a point to put skeptical reporters in a car with George W., so that they wouldn’t have to take it from a paid flack that the guy was absolutely passionate about this stuff!

So she proceeded to work the Marlin tableau into his speeches, in language that one seldom heard from the lips of any politician, much less a conservative: “Each of us holds a piece of the promise of America. That young man at the jail in Marlin wasn’t sure. He wasn’t sure the promise was meant for him. He didn’t know whether he still had a shot. Yet some spark was alive. He was willing to risk asking the governor, What do you think of me? He meant, Is there hope for me? Do I have potential? Can I make it? Do I own a piece of the promise of America? In the mightiest and wealthiest and freest nation in the world, he still wasn’t sure. And that’s a tragedy.”

(Sometime after his chance encounter with George W. Bush, Baulkmon was raped by another juvenile offender while serving time in a TYC detention facility. Though the meeting in Marlin would become a centerpiece of Bush’s nomination acceptance speech in 2000, Baulkmon did not learn of his fleeting fame until years later, after, apparently unconvinced by “the promise of America,” he had become an adult petty criminal. In 2006 Baulkmon would appraise Bush thusly, from a Beaumont prison visitation room: “He doesn’t care about anything but himself. He’s complete trash, a horrible, evil person.”)

People were talking about him, and that was fine. But as heady as it all was, Bush had just gotten comfortable in Austin and was not of the mind to make any sudden movements. When his dad’s old campaign manager, Bob Teeter, had come to town in 1997 and visited with Rove, Hughes, longtime Bush ally Don Evans, and others about the possibility—just the possibility—of the governor’s running for president, Hughes had shut down the whole thing. “This is way out in front of where I think the governor is,” she said.

Still, he let Rove talk him into a road trip.

On April 24, 1998, Bush arrived at the Palo Alto residence of former Secretary of State George P. Shultz. Inside were the big thinkers of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution: former Ronald Reagan economic advisers Martin and Annelise Anderson; economist John Cogan; the college’s impressive young provost and Sovietologist Condoleezza Rice; and the man who had organized the meeting, Michael Boskin, the former director of the Council of Economic Advisors under George H. W. Bush. Bush came prepared, but he was relaxed as Shultz made the introductions. Noticing that his host had a Hispanic housekeeper, the governor spoke to her in her native tongue, to her tittering delight.

They sat in Shultz’s living room, where coffee and cookies were laid out on a table. The host began by saying, “Some of you may remember another meeting we had here with a governor.” That governor had been Ronald Reagan, back in 1979, when many of these same big thinkers were sniffing him out to discern whether he was really the dunce everyone said he was. They came away thinking entirely the opposite, and thus did the conservative intelligentsia throw its gray matter behind Reagan’s 1980 campaign.

And now here was George W. Bush, about to provide a powerful dose of déjà vu. After listening to his hosts give presentations on budget policy, taxes, economic outlook, entitlements, Social Security, and international affairs—and being professors, each went overtime—Bush spoke his piece.

“I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about these things, some of them back when I was working on my dad’s campaign,” he said. “I’m thinking about running, but I’m not here to make any announcement. I’ll be making up my mind over the next few months.”

He talked about Social Security, saying, “I’m going to spend the political capital necessary to fix it.” He agreed with Cogan’s comment that budget surpluses usually ended up getting spent by Congress: “Yeah, that’s a problem with all legislative bodies, isn’t it?” He expressed great interest in India, which none of them had expected of a Texas governor. For several minutes he listened intently as Shultz, Boskin, and Rice debated whether or not the International Monetary Fund should be reformed or abolished altogether. And though he asked numerous questions, the Hooverites noticed that he did not frame them as “What should I do?” but rather “Here’s what I’d do. What do you think?”

When it was over, Shultz rather giddily took Bush aside. He told him that back in 1979, after Reagan’s talk had concluded, Shultz had brought him to the very spot where they now stood and said, “Run. We will support you.” And now, Shultz said, he wished to say the same thing to Bush.

“The thing is,” the governor said, “I have to be sure that my family’s comfortable with it. Also, I want to make sure there are significant things that I want to accomplish as president.”

Which only made Shultz giddier: My God, just like Reagan. An agenda president.

“I’m just not gonna do this,” said Bush one summer afternoon to Hughes as the two of them drove to an interview in Dallas. “I want my girls to have a normal life.”

He was genuinely torn: flattered by all the Republicans showing up at his door but remembering well how the daily muggings of his father’s 1992 campaign had left every Bush gasping on the mat. Why go through it again? He didn’t need this.

His 1998 gubernatorial campaign was at once a silly formality and overwrought with portent. Even though he was a million points ahead of Garry Mauro, he was still out there, sweating completely through his clothes at a diner in Beaumont. Was he just restless? Running up the score to qualify for the big tournament? National reporters tailed him everywhere. The Democratic National Committee was giving Mauro all the support necessary to at least knock Bush down a notch. Meanwhile, and very quietly, a Dallas attorney named Harriet Miers was overseeing an extensive in-house opposition research effort, gathering all the goods against her friend George W. Bush so as to be ready for the onslaught.

This, of course, included the DUI incident in 1976. “What do you think we should do about this?” Hughes asked Bartlett and campaign press secretary Mindy Tucker one day.

The two agreed: Get it out there. If that’s the worst there is, we can deal with it.

But Bush had already made his decision. While submitting to jury duty, the governor was approached by a reporter who asked, “Were you ever arrested for drunken driving?”

“I did a lot of stupid things when I was young,” Bush replied.

He left it at that. Bush’s daughters were just beginning to drive at the time. “I’d made a conscious decision not to spend time talking to them about stupid things I’d done,” he would later say. “And so I made the decision there on the spot—this is without any consultation, not sitting around with the Bartletts or the Hugheses of the world on how to handle it.”

Rove would regard his failure to change Bush’s mind on the subject as his biggest mistake of the presidential campaign.

The gears began to whirl on November 3, 1998. Mike Boskin began to prepare briefing books on every national issue. Straining at the leash of strategic ambiguity, Rove’s mind thrashed as he contemplated the primaries before the primaries, the primary of money, the primary of ideas: Gotta show that we’re innovative and for God’s sakes prudent … he’s only dealt with state economic issues, his foreign policy’s limited to Mexico … gotta blow out his four big issues to national scale … need a policy shop, building on what we did with Judge Gaither and Sandy Kress and Marvin Olasky … bring ’em in, let ’em teach, but let ’em also be impressed, like the Hooverites, they’ll be part of our cheerleading squad …

Bush’s language had changed, leaning more toward yes—“I’m thinking very seriously about it,” “Keep your powder dry”—but even with decision-making time absolutely upon him, the man who seven years later would refer to himself as the Decider was anything but. And though Laura had come on board—in many ways showing less reluctance than she’d displayed before the gubernatorial campaign—the girls were in revolt. They’d seen how the press lampooned Chelsea Clinton. How could a father put a daughter through such humiliation?

“My attitude was ‘Someday you’ll understand why,’ ” Bush would recall of these impasses. “Laura did a lot of that too.” The twins did not go quietly. Shortly after the election, an adviser visiting the mansion could not help overhearing the governor upstairs having a yelling match with Jenna. The issue was whether or not his daughter could spend Thanksgiving with friends in Mexico. The father was trying to explain that, considering what was at stake here, gallivanting off to Mexico might not be a very good idea.

Jenna responded with her own unbiased prognostication: “It’s not like you’re gonna win!”

The morning of Governor Bush’s second inaugural ceremony, he sat with his family in an Austin church for what he had assumed would be an obligatory prayer service. But Pastor Mark Craig had something else in mind. People are starved for leadership, the pastor declared. Starved for leaders who have ethical and moral courage … And it’s not always easy or convenient for leaders to step forward. Even Moses had doubts …

“He was talking to you!” Barbara stage-whispered into her eldest son’s ear at the conclusion of the service. And though ever-modest Laura countered with “He was talking about all of us,” Bush was in the full throes of epiphany. Like that, the pastor’s words became the godly hands that pushed him clean off the prepresidential bubble.

Bush declared his exploratory committee open for business in March of 1999, at which point the very shadow of his candidacy began to suck the life out of campaigns already in progress. In the first 120 days of the campaign, his finance chieftains Don Evans and Jack Oliver worked the moneyed faithful, hoping to raise around $20 million. Before long, FedEx boxes full of checks began to accumulate in the office of Oliver’s assistant, Kate Walters, stacked up like missiles in a silo. On the first of July, at a campaign stop in San Jose, California, Bush announced the tally, to astonished gasps: $37 million. (“That’s three times the amount my dad raised,” he later pointed out to a family friend.)

Back in Austin, the governor presided over one last legislative session, adding another $1 billion tax cut to his portfolio. He showed up late to the August Iowa straw poll competition and rolled over the opposition anyway, ten points ahead of Steve Forbes. Then he returned home, to meetings at the mansion with the nation’s most prominent conservative economists, domestic policy innovators, and foreign affairs sages. He was getting schooled, but so were they. The governor’s “useful impatience,” as one participant would put it, was ever on display. He delighted in his ability to outwit the brainiacs, drilling down to profound simplicity with questions like “What do we have an army for, anyway?” and never letting these big thinkers forget who was in charge. During one dinner meeting at the mansion to discuss economic policy, Bush led off by saying, “If the American people wanted an economist for president, you guys would be running and not me. But they don’t.”

Fortified with big thoughts and deployed with exquisite choreography by Rove, Bush would materialize in Los Angeles or Indianapolis or Charleston or some other carefully chosen venue and, amid a riot of TV cameras, roll out some new proclamation of Bush policy. The speeches, penned by newly hired scribe Mike Gerson, were freighted with detail and lofty allusions and in some other context would have seemed pompous. But this was a campaign already starched up as a presidency—so inevitable, so forceful and precise as to almost appear preexisting, as if George W. Bush, the governor of the nation’s second-largest state, had practically been running the nation for some time already. As if this man who would presume to improve upon an era of Peace and Prosperity had already passed all the requisite tests.

Which, you could say, he had.

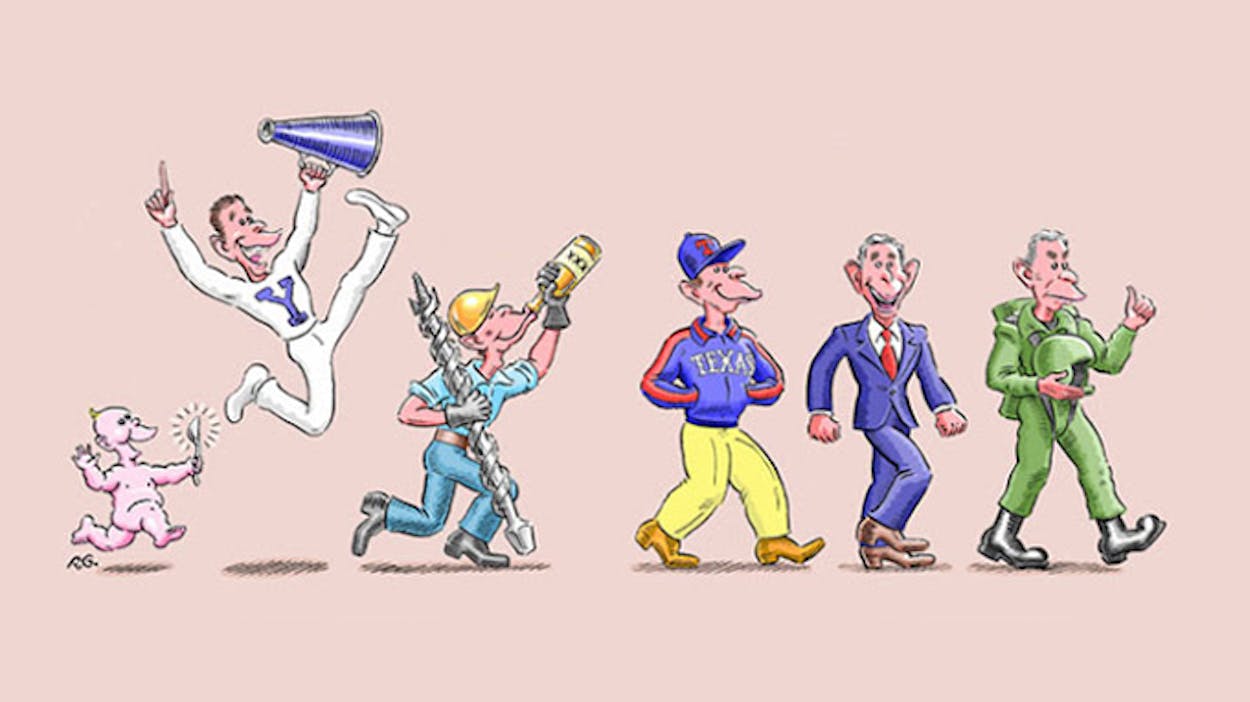

For he had started at the bottom of the oil business and wound up a rich man (a test of his entrepreneurship … or of his extraordinary connections).

He had distinguished himself as a dynamic co-owner of a baseball team (a test of his executive shrewdness … or of his cheerleading skills).

He had waged a successful underdog campaign against a popular governor (a test he inarguably passed … or which Ann Richards and the Democratic party indisputably failed).

And he had become a bold and popular governor (whose agenda depended on the efforts of the far more powerful Democratic leadership).

These were the tests George W. Bush had passed with flying colors. He’d made it all look easy. None of it was easy.

None of it was enough.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Books

- Longreads

- Karl Rove

- George W. Bush