In downtown Midland, at the intersection of Marienfeld Street and Michigan Avenue, stands a simple five-story concrete office building. It is not much to look at—it’s squat and boxy and dull yellow in color—but once it was the home of a corporation that earned $870 million in annual revenues. Today it is part of the residue of the late, great oil boom that affected Midland as much as any oil town in America. In this it is like half a dozen flashier buildings that dot the Midland skyline—all of them built with oil money, all of them constructed because people believed that the oil boom would last, if not forever, then certainly for a good long time. And why shouldn’t they have believed it? Wasn’t everybody saying that the price of oil was going to keep rising—to $50 or $60 or maybe even $70 a barrel? During the boom there didn’t seem to be any reason to doubt that, especially if you lived in Midland. But everybody was wrong; the oil boom couldn’t last forever, and by the early part of 1982 it was over. And today some of those new buildings, like the one at Marienfeld and Michigan, stand as reminders not so much of how good the good times were but rather of how quickly everything fell apart.

The building was occupied in January 1981, at the height of the boom. When it was first opened, it was called the CPI Building, short for Consolidated Petroleum Industries, which was one of the great success stories of the boom. Founded in 1978 by a Midland dentist named Jack Young and an Abilene oil buyer named D. Truitt Davis, CPI grew so quickly that by the time it moved to the new headquarters, its tentacles were all over the oil patch. Its drilling subsidiary had fifteen rigs running from the Austin chalk to Oklahoma. Its exploration arm had snapped up leases on more than 100,000 acres and was putting together deals to search for oil and gas. It owned a handful of oil service companies: a mud company, a wireline company, a chain of oil field supply stores. It had a small refinery in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and a crude oil trading company and a marketing company too, all of which were making money. Indeed, by 1981—just three years after its founding—CPI owned 21 subsidiaries and employed more than nine hundred people. Had it been eligible for the Fortune 500 that year (it had not been a public company long enough to qualify), it would have ranked 339th, ahead of companies with such familiar names as Champion Spark Plug, Miles Laboratories, and Pabst Brewery. When, two months after moving into its new building, CPI did make a public offering of stock, Young and Davis were suddenly worth $25 million and $36 million, respectively, for their CPI stock alone.

Today nobody in Midland calls the building at Marienfeld and Michigan the CPI Building. What the oil boom giveth, the oil bust taketh away, and for a company like CPI, situated precariously atop the crest of the wave, the bust spelled disaster. After twenty months in its headquarters, CPI moved out; these days you can scarcely tell the company was ever there. The only evidence that remains is in one corner of the fifth floor. That’s where Jack Young has his office, just as he did in the old days, before the bubble burst for CPI.

The Bright, Sparkling Mistake

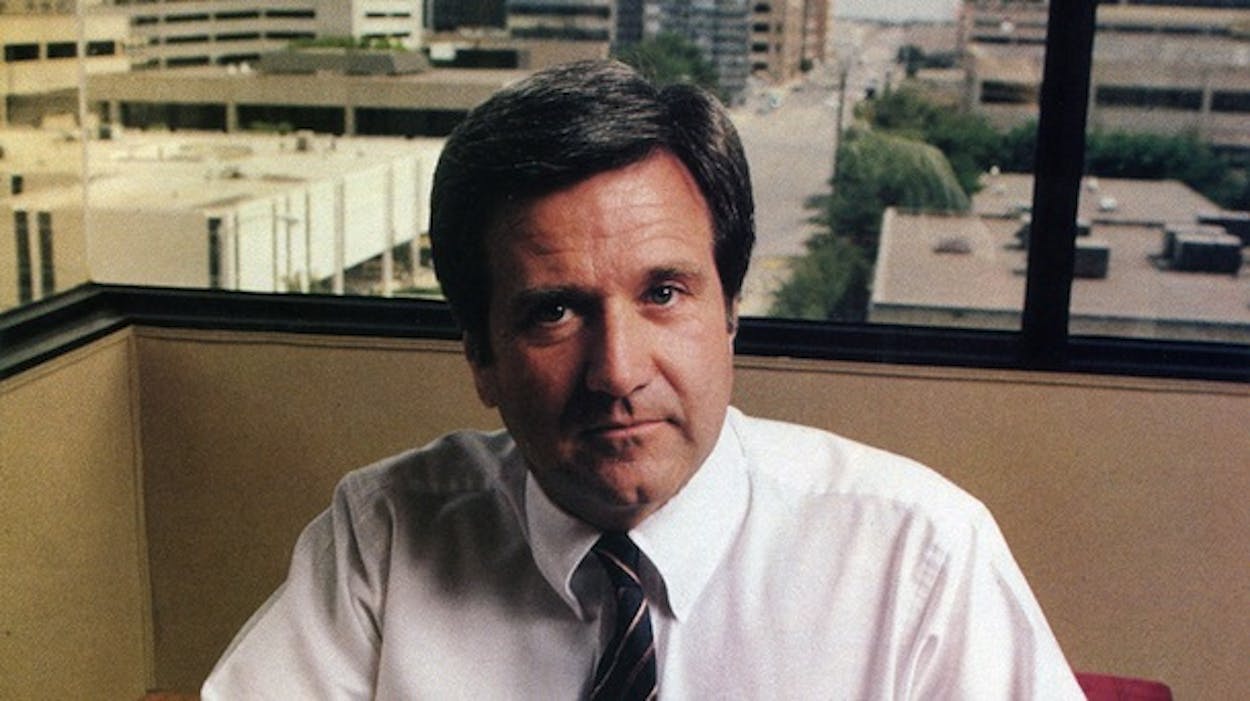

One afternoon toward the end of March, Jack Young showed me what was left of his once-thriving empire. He is a friendly, easygoing man of 48; his hair, graying gracefully, is brushed high across his head in the old Kennedy style, and his classic, Horatio Alger looks are only just starting to be softened by age. His two most distinctive features are his voice, which seems oddly soft coming from someone who looks so much like an ex-jock, and his bright blue eyes, which have a puppy-dog sadness to them. The hurt in those eyes increases perceptibly whenever Young talks about the company he once ran. For the rise and fall of CPI—a company that was so completely a creature of the oil boom that it couldn’t thrive in any other environment—is also to some degree the rise and fall of Jack Young, Midland dentist turned oilman.

We met on the fifth floor of the CPI Building. His own office, with its richly woven carpet and assortment of comfortable armchairs, is quite plush, and in the hall, between an empty reception desk and two empty visitors’ chairs, stands a lone piece of corporate art—a small sculpture the company had bought to adorn its headquarters. Then we went out to the parking lot, climbed into Young’s Bronco—”One of my children has the car today,” he said in a tone of voice that made it clear he was apologizing—and headed for the outskirts of town.

We drove for several miles along one of the main highways leading out of Midland and then crossed some railroad tracks and started up an access road. All along this road stood small, nondescript industrial buildings, most of which had signs out front that made it unmistakably clear that we were in the oil patch: Tom Brown Inc., Tahoe Drilling, GCG Drilling, Ike Lovelady Inc., and a dozen others. I looked past the buildings into the large yards behind them, and I could see, wherever I looked, the accoutrements of oil. In better times you would have seen a lot of hustle and bustle around these buildings, but you probably wouldn’t have seen much equipment. Most of it would have been out in the oil field, making money. Now you could see what the oil bust had wrought in Midland. Shallow rigs, sitting unused, loomed up from almost every yard, like giant tombstones. Mud pumps, which had been so valuable during the oil boom because they were in such short supply, were scattered everywhere, keeping company with idle engines and fuel tanks. And most of all, there was pipe—stacks upon stacks of it, as far as the eye could see, of infinite variety. Much of it was rusting.

Young turned into a driveway leading to one of the yards. According to a sign at the entranceway, the yard was owned by a company called Tierra Drilling, a subsidiary of CPI. The yard was being used as a place to store—and sell off—equipment that belonged to a number of the old CPI subsidiaries. Young walked through the door of a one-story L-shaped building that looked like a long, misshapen mobile home, and pointed to the second cleaned-out reception desk we’d seen that morning. “I think she was let go last week,” he said. “Saves a little money.” He poked his head into a few offices, said hello to the half-dozen people at work, and then went back outside.

At the far end of the yard a crew of four men was cleaning some bulky drilling apparatus, but otherwise everything was still and empty; as we walked we could hear the echo of our footsteps. We stepped first into a large, open garage next to the office building, where we saw two Mack truck cabs, three pickups, a boat, some trailers, and assorted pieces of large equipment sitting on flatbed trucks. “Most of this is from the pumping service, and chemical companies Truitt Davis started up around the end of 1981,” said Young. “The companies ended up shutting down almost as soon as they were begun because that’s when the bottom started falling out for us.” The equipment, practically new, had been sitting in this garage ever since.

We moved on to the first of a series of hangarlike structures and poked our heads in. The room was filled with the flotsam and jetsam of white-collar work—desks, chairs, file cabinets, Rolodexes—most of it taken from the CPI Building, all of it now gathering dust. In the next hangar were six metal shelves stocked with small oil field supplies and, off in one corner, about fifty cans of industrial paint. On the floor sat two cardboard boxes filled with telephones, including several car phones. “This is all we’ve got left of Dunnam Tool and Supply,” said Young, gesturing toward the shelves. Dunnam Tool & Supply was the name of the supply store chain CPI had owned during the boom. “We’re still trying to sell this stuff off.”

Soon we reached the first of a number of CPI-owned rigs that lay on their sides at various points around the lot. These were not the shallow rigs I had seen in other yards on the drive in; these were deep rigs, capable of drilling between 12,000 and 16,000 feet into the ground. During the boom CPI had gone heavily into debt to accumulate a fleet of fifteen of these deep rigs, at a cost of about $4 million each. At the time it seemed like the smart thing to do; deep gas plays were the sexiest plays in the oil patch, and investing in deep rigs seemed like a no-risk proposition. But then the natural gas market dried up, and CPI was stuck with fifteen hugely expensive rigs no one could use—and a debt it couldn’t repay.

The rig in front of us was about 130 feet long, and like the others in the yard, it had been given a fresh coat of white paint. It sparkled. Young looked at it for a long time without speaking. As he continued to gaze at it in an almost meditative silence, that rig at that moment seemed suddenly to symbolize for him all the things that had ever gone wrong for CPI. He shook his head slowly, in a gesture that implied both resignation and disbelief. Finally, turning to walk away, he said, “Of all the mistakes we made at CPI, building these deep rigs was probably the biggest mistake of all.”

Jack Young, of course, is not the only man in Midland, or in Texas, whose fortunes fell when boom turned to bust. Two years ago, as the price of oil rose to $34 a barrel, the oil patch was full of people with high hopes and big dreams; today, with oil back down to $29 a barrel, it is littered with the casualties of the bust. Almost everyone who hitched his fortune to the oil boom—whether in Midland or Houston, whether company president or roughneck—is now suffering the consequences of that decision, just as Jack Young is.

How did it happen? How did things go so sour so quickly? In Texas the conventional wisdom has it that the bust is the result of forces beyond our control—in particular, the oil glut created when OPEC lost its grip on the price of oil. And certainly there is a good deal of truth in that explanation. But to spend time in Midland is to realize that you can’t blame it all on OPEC. Midland during the oil boom was like California must have been during the gold rush or Wall Street in the twenties, just before the crash. People scrambled in from all over to cash in on the boom, and more than a few of them were greedy. Suddenly the imperative wasn’t just to get rich in the oil business, it was to get rich right now. A kind of mass hysteria took over in the oil patch, and even normally rational, sober, intelligent businessmen got caught up in the frenzy. So companies started borrowing more than they should have and growing faster than they should have, and out in the oil field they started to swing for home runs with every well. In a way, they set themselves up for their own fall.

What happened to Consolidated Petroleum Industries is fairly typical of what happened in the oil patch. It’s not accurate to say that the company was done in by a handful of faraway oil ministers; CPI did too many things wrong for that to be true. But neither is it right to say that the company’s collapse was due solely to its own mistakes. Fifty-dollar-a-barrel oil, had it ever come to that, would have made up for a lot of mistakes—and besides, many of the decisions CPI made were no different from decisions everybody in the oil patch was making. What is fair to say is that somewhere along the way the people running CPI crossed the line that separates entrepreneurship from gambling. They gambled that the boom would last, and they lost.

The Perfect Partnership Gets Consolidated

It’s a sweet bit of irony that Jack Young is a dentist, because in Midland oil circles there is hardly a stronger term of opprobrium. “Every dentist in town thinks he’s an oilman” was the boom-era maxim. Today, a phrase you hear a lot around the Petroleum Club is “the dentists are back drilling teeth,” and it’s usually said with no small amount of self-satisfaction.

“Dentist” connotes amateur, but in Jack Young’s case, that’s a little unfair. Young had been doing oil deals for twenty years before starting CPI, and in some areas of the business, he really did know what he was doing. He had moved to Midland in 1959, fresh out of the Baylor School of Dentistry, and set up what quickly became a thriving practice specializing in children’s dentistry. But it wasn’t long before he caught the oil bug, and by the early seventies Young was spending as much time on his side ventures—mostly oil and real estate—as he was on children’s teeth.

From the first, Young did most of his deals with an Abilene oilman named D. Truitt Davis—or more accurately, Davis did most of his deals with Young. Davis was the chief instigator of deals. Young’s role, especially at the beginning, was as an investor in Davis’s deals.

Truitt Davis was not then—and is not now—your typical West Texas oilman. He is on the editorial advisory board of the Oil Daily, the newspaper of the oil patch, and has served on various boards and commissions throughout his career. But his name seems to carry more weight in Austin and Washington than it does in West Texas, where he is considered something of an odd duck. This is partly because Davis is a crude buyer and refiner, and crude buyers are always viewed with a little suspicion by the oilmen who sell their crude to them. But it’s also because there is about him a slight aura of mystery. In a business full of back slappers, Truitt Davis is a loner. In a business full of braggarts, he keeps his own counsel. He is, at 53, a small, gaunt man with hollows for cheeks; his white hair is combed upward into a kind of modified pompadour, and his weakness for expensive suits makes him look more Wall Street than oil patch.

Above all else, though, Truitt Davis is an irrepressible idea man—with the overriding idea being to create new “profit centers” (to use a favorite Davis expression). Davis is one of those people who can scarcely do anything in life without seeing in it some possibility to make money, and while over the years he came up with his share of schemes that his associates thought were just this side of loony, he was just as often right on the mark. For instance, after the discovery of oil in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay, Davis (with Young as a partner) was the first independent to build a refinery in Alaska. Its proximity to crude made that refinery a live profit center for Young and Davis; even before it was finished they sold it to Tesoro Petroleum for a cool $10 million in Tesoro stock.

By the mid-seventies Jack Young had given up his dental practice to spend full time on his various partnerships with Truitt Davis. By all accounts they made a good team. Davis’s natural reticence was offset by Young’s talent for talking up deals to prospective investors and bankers, and Davis’s gift for coming up with ideas was matched by Young’s ability to bring those ideas to fruition. If Davis was the big-picture man, then Young was the detail man. For a while it looked like a partnership made in heaven.

Just after Young quit dentistry, he and Davis built a small, five-thousand-barrel-a-day refinery in Lake Charles, Louisiana; this project was the first in a series that would eventually lead to the formation of CPI. The idea for the project, of course, came from Davis; Young’s job was to raise the money to build the refinery and to oversee its construction. The Calcasieu Refinery (as Young and Davis christened it) was clearly one of Davis’s better schemes; when it was put into operation, it was an almost instant money-maker. Its success was due to its proximity to a port and also to a new federal program called the small-refiner bias, which gave substantial subsidies to small refiners so they could compete with the major oil companies. Before long the new refinery—along with a crude buying and marketing operation that revolved around it—was earning, in a good month, about $1 million for Young and Davis.

After the refinery was completed, Davis bought out most of the partners in his various other ventures, except for Jack Young. With this act, Davis and Young became true partners, their business interests completely entwined. And the plan was for them to stay that way. It was just around this time too—1976 and 1977—that you could see the dawn of the boom. The Hughes Tool Company’s rotary rig count, which calculates the number of rigs in use at any given moment and is the chief barometer of the industry, was rising steadily, from around 1600 in 1976 to 2000 in 1977 to just under 2300 in 1978. So there was expansion in the air—albeit slow and cautious expansion. This helped stir in the two new partners a feeling that they shouldn’t be content to stand pat with what they had, even though it was making them richer than they had ever dreamed.

Soon Young and Davis were doing a little slow and cautious expansion of their own. They set up a company to market refined products, which they named Beaumont Oil. They expanded Davis’ crude buying business. And over at the refining company, Young and Davis brought in, first as consultant and then as president, a young man named Michael M. Fowler, who went by the nickname Mack. Fowler, born in Odessa and trained at Harvard, was not without ambition himself—that was one of the things Young and Davis liked about him—and he came to Calcasieu with his own expansionist plans. Under his direction the refinery’s capacity grew from 5,000 to 16,000 barrels a day.

Up to that point, Young and Davis had stayed with the business they knew best—the buying, refining, and selling of oil. In June 1977, however, they took their first step into uncharted waters: they formed a drilling company. The deal developed after Young was approached by a friend of a friend who knew about a chance to pick up three rigs for $1 million. The friend’s friend, an utterly self-confident 29-year-old drilling company salesman named John Jacobs, wanted to use those rigs to start up his own company, but he needed someone to stake him. In the days when he was on top of the world, Jack Young heard his share of entreaties like this—it’s a natural part of life in Midland once you get a reputation as someone with “cash flow”—but this time he was intrigued. With the boom heating up and rigs in short supply, drilling companies were already cashing in, commanding in many cases $4,000 a day for work that used to cost around $2,500.

Young took Jacobs’s proposal to Truitt Davis, who took an immediate dislike to it. Drilling was too cyclical, he said; he’d seen drilling booms before and they’d always tamed into busts sooner or later. But Jacobs was persistent, and eventually he heard the answer he wanted: Young and Davis would get him started in a drilling company—although they vowed to sell it as soon as it was off the ground. Young and Davis borrowed the money from the Abilene National Bank, bought the rigs, and turned them over to Jacobs. And then Jacobs set about making Young and Davis look like geniuses. Within a year the new drilling company had retired the loan, built two additional rigs, and was beginning to get work from some of the larger independents and even the majors. Within a year and a half it had added two more rigs, bringing the total to seven, and had plans to build still more. By the time all the rigs were in place the company was making around $175,000 a month in profits, and Truitt Davis had stopped complaining about the cyclical nature of the drilling business. On the contrary, after seeing how well the drilling company was doing, Davis and Young dropped their plan to sell; instead they financed several other men in similar enterprises. One was Dunnam Tool & Supply. Another was a mud company—”mud” is oil patch jargon for fluids used in drilling wells—called Technical Fluids. In creating these companies, Young and Davis put up all the money, but the company presidents were given substantial stakes in their businesses as incentive. It seemed to work; each new venture made money for Young and Davis.

All of these companies were in place by the fall of 1978. The next step, which took on increasing urgency as the companies began to grow, was to combine them all into one large enterprise. And in December 1978 Young and Davis did exactly that, naming their new company Consolidated Petroleum Industries.

Young and Davis had a number of persuasive-sounding reasons for wanting a single large company instead of several small ones. For one, they felt that a large, diversified oil company would have a better chance of surviving over the long haul. The oil business was cyclical, after all; if refining suddenly went down the tubes it would be nice if the company had producing wells that could pick up the slack. For another, although the management style of Young and Davis was loose in the extreme—they believed in giving their company presidents great autonomy —they hoped that the creation of a parent company in which everyone had a stake would breed a little less empire building and a little more team spirit on the part of the division heads. In this, they completely misjudged the people they had put in charge of the divisions, but by the time they figured that out, it was too late. And in any case, when CPI was born no one was thinking much about what might go wrong. The oil boom was gaining steam, and it was hard to imagine that anything could go wrong.

Young and Davis had to take care of one other bit of business before CPI came into being. They had to find people to serve on the board of directors. Like any new corporate executives with big ideas, they wanted a board full of big, important people. Through an Austin acquaintance of Truitt Davis’s, they met Frank Ikard, a Texan who for many years had headed the American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry’s most prestigious lobbying group, and who was now a Washington lawyer. They asked him to be on the board, and he accepted. Ikard knew Walter Cronkite so there was some talk of getting him to come on the board. They asked Barbara Jordan, but she turned them down. Another person they talked to was William L. Fisher, the respected head of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas and an Assistant Secretary of the Interior during the Ford administration. Fisher, another acquaintance of Ikard’s, accepted. Their last board member (Young and Davis were on the board, of course) was not a VIP by Austin or Washington standards, but there was hardly anyone more important to the fortunes of the new company. His name was Don Earney, and he was the president of the Abilene National Bank. He was CPI’s banker.

The Cussing Banker With the Full-length Mink

“I don’t give a shit how many people you talked to. Nobody saw the price of crude going to the bottom overnight.” Don Earney took a swig from a bottle of soda, swung his feet up onto his desk, and glared at me defiantly. This was his capsule summary of what had gone wrong in the oil patch, and he was just warming up. “Hell, yes, it would have been smart [to have been more cautious in making energy loans],” he growled. “F— yes. It would have been goddam smart to have done that. But at the time, hell, no. When the Dallas Cowboys are on a winning streak . . . do you say, ‘Hey, boys, we better not play very hard this week? Let’s shut this sonuvabitch down?’ ”

Don Earney is no longer president of the Abilene National Bank, and the loans he made to oilmen are the main reason why. It wasn’t just oilmen who gambled on the boom, it was bankers too; a lot of the loans they made that fueled the boom were predicated on continued good times. When things went bad the banks had to suffer the consequences. Continental Illinois of Chicago, one of the most aggressive lenders during the boom, had to write off $236 million in energy loans and has another $605 million in so-called nonperforming loans. Four vice presidents have resigned as a result. First National of Midland, the largest independent bank in Texas, announced last December that it had $150 million in nonperforming loans. Its chairman, Charles Fraser, resigned this past April. There are a slew of other banks—the most conspicuous being Penn Square in Oklahoma City, which collapsed under the weight of its energy loans—whose fortunes suffered similarly when boom turned to bust.

For Don Earney, the roof fell in on August 5, 1982, when the Mercantile Texas Corporation, the fifth-largest bank holding company in Texas, took over Abilene National. The takeover was forced on Abilene National by federal bank examiners who felt that Earney had made too many boom-time energy loans that the bust had rendered uncollectable, a judgment at which Earney takes great umbrage. In the end, the bust hurt Earney as much as it hurt any single person in the oil patch. He lost his job and the bank he had built up almost single-handedly. He lost several other smaller banks in Texas that he also owned. Because Mercantile paid nothing to Abilene National’s stock-holders, Earney’s small bank holding company lost about $56 million after the takeover, and Earney himself lost $4 million. And perhaps most painful of all, Earney lost that wonderfully seductive feeling, which he had long relished, of being the biggest fish in the pond. Of all the people I talked to for this story, Earney feels most bitterly that he was done in by forces completely beyond his control.

On the other hand, it is hard to imagine anyone in West Texas who ought to have had more control over his own fate. No one was twisting Don Earney’s arm to make those loans. Just as with the oilmen themselves, those banks that stayed a little cautious during the boom, that didn’t accept as absolute gospel the predictions that oil, in Don Earney’s phrase, “would go to a hundred dollars a barrel,” are the ones that are still healthy.

I started to make this point to Earney when I talked to him, but he cut me off. He was having none of it. “You have to get your body and your system and your mind into the times,” he said; only if I understood how frenzied the oil patch had become could I understand why bankers like himself had acted the way they had. To Earney’s way of thinking, that frenzy had forced the hand of banks like his. Every deal, it seemed, had to be done today, or someone else would do it tomorrow. Every rig had to be bought right this minute because there were six other people standing in line for it. The gold rush mentality had taken hold, and banks unwilling to make loans on that basis simply didn’t get the business. And the business was what Don Earney wanted most of all.

But I had heard enough stories in Midland to know that the bankers themselves had contributed their share to the hysteria that overtook the oil business. If the oilmen were the ones actually panning for gold, then the bankers were the ones sending out leaflets with promises of untold wealth. During the boom the Midland Hilton was supposedly so full of bankers that you had to make a reservation three weeks in advance to get a room there. There were stories about bankers’ coming to West Texas and staking people who had never done an oil deal in their lives; stories of bankers’ dangling the promise of loans in front of longtime industry employees in the hope that they would quit and form their own company; stories of bankers’ scouring the streets of West Texas looking for oilmen to lend money to. “Bankers I had never met would come by my office all the time,” one oilman recalled. “They’d want to know did I need any money for anything I was working on? Was I going to be working on anything soon they could participate in? Anything. It was unbelievable.”

Don Earney was the quintessential boom-time banker. He wanted to build up his bank as fast as possible, and making energy loans during the boom was the fastest way there was. When he bought Abilene National in 1976—he had been a regional head of the Federal Housing Ad-ministration before that—it had $20 million in assets. When he left six years later, the bank’s assets hovered around $500 million. On his own terms, at least, he was a roaring success.

He was also a flashy man, cut not at all from the cloth of a typical banker. He was a cusser of considerable repute. He wore the customary Rolex, of course, and his employees once bought him a full-length mink coat. He owned a black Porsche 911SC. He seldom socialized—he spent too much time at the bank for that—but he could be a grandstander when the occasion called for it. When the Abilene National opened its brand-new headquarters building in 1980, the local paper printed a picture of Earney standing outside the bank, holding a string of $100 bills. That was classic Earney. He was a salesman as much as a banker, and the product he was selling was the Abilene National Bank.

At the height of its indebtedness Consolidated Petroleum Industries and its various subsidiaries owed Abilene National about $34 million in loans and letters of credit. (The much larger Continental Illinois held $51 million of CPI’s debt and also at one point gave the company a $15 million revolving line of credit.) Unlike Continental Illinois, which preferred to make loans to the company’s more traditional endeavors, like refining and drilling, Abilene National put up the money for what were clearly CPI’s riskier ventures: for instance, $4 million for a hydroelectric project Truitt Davis wanted to start up in California (it is still operating today, although it has never made a penny in profit) and another $2.5 million to start up the pumping service and chemical companies, neither of which ever really got off the ground. Earney claims that he carefully considered every deal brought to him by Young and Davis, and even turned them down from time to time, but mostly he was on the team.

Several people suggested to me that part of the reason CPI had such an easy time getting money out of Abilene National was because Earney and Davis were unusually close. Certainly they were friends. Davis’s principal office was located in the Abilene National Bank building, and he (as well as Young) was a stock-holder in six of the banks Earney owned. And of course Earney was on Davis’s board of directors. But it seems more likely that Earney treated Davis and Young the same way he treated everybody he did business with. If he liked you and believed in you, you got your money. That’s the way he operated. One former Abilene National customer says, “Don Earney was the kind of guy who would say, ‘I think your deal sucks, but here’s the money.’ ” Earney himself describes his banking philosophy, then and now, thusly: “I don’t give a f— what [the project] is, I loan money to the sonuvabitch sitting across the table from me. If you loan money to the man and if you believe in him, he is going to figure out a way to pay you back.” But even as the boom was reaching its height, two of the men Don Earney believed in most strongly, Truitt Davis and Jack Young, were beginning to lose control of their company.

The Road Show That Went First-class

It was May 1980. With the rig count closing in on three thousand, boom fever had struck, and that was especially true of new—and newly prosperous—companies like CPI, which were furiously expanding. Indeed, during its first year and a half of operation, CPI seemed to be doing nothing but expanding. Dunnam Tool & Supply was in three cities instead of one. The drilling company was up to fifteen rigs, including those deep rigs that looked so lucrative at the time. CPI got into the wireline business and the well service business and half a dozen others. Everyone at CPI got caught up in the excitement, but none more than Truitt Davis, who was simply bubbling over with ideas for expansion. He liked to call his friends in the middle of the night to talk about new ideas—about plans to create new subsidiaries or to buy new equipment or to get into a different part of the oil business. Once, during such a phone call, he mentioned to an employee that what he really wanted to do some day was buy an offshore rig. That offshore rigs cost around $50 million seemed not to faze him in the least. The boom was on, and everything seemed possible.

That May, CPI’s board of directors held a meeting in the London office of a European subsidiary it owned. What transpired in that meeting is recorded in company minutes, and to look at those minutes today is to get a clear sense of just how heady an experience running CPI was for the men involved and how grandiose their plans were. Davis, as chairman of the board, brought the meeting to order and after a few preliminaries gave Mack Fowler the floor. Fowler wanted to talk about his latest expansion plan, “the Calcasieu Terminalling project in Lake Charles, Louisiana, which will include two million barrels of storage for crude oil, deepwater docks, and four pipeline connections to major pipelines. The anticipated cost,” noted the minutes, “is between $15 and $18 million,” which Fowler hoped could be paid for through tax-free bonds issued by the Lake Charles Port Authority. The directors gave their unanimous approval to the idea.

Then the discussion turned to the upheaval in Iran, which company officials feared would hurt CPI’s ability to get crude oil for the refinery. “Indications are that the banks [Abilene National and Continental Illinois] would provide financing for up to $40 million to handle a build-up in inventory . . . to protect the Corporation’s position.” So the board passed a motion authorizing the company to start buying $40 million worth of inventory.

Next on the agenda was a discussion of CPI’s debt. “The Corporation,” noted the minutes, “currently has approximately $21 million borrowed . . . of which $4 million is required to be paid off during the next 12 months. It is in the best interests of the Corporation to restructure the Corporation’s financing by rolling in present borrowings into a $25 million . . . loan.” The minutes added, “The Corporation should also seek a $10 million to $15 million revolving credit line.” Motion passed.

After a few more such presentations, Mack Fowler again took the floor, this time to “present a proposal to expand the refinery capacity.” What Fowler actually had in mind was a scheme in which Calcasieu would more than quadruple its capacity—to about 70,000 barrels a day—”at a cost of approximately $104 million to $120 million.” This project would be financed, according to Fowler’s scenario, partly by putting aside Calcasieu’s profits for the expansion and partly by cutting a deal with the much larger Superior Oil. Apparently no one blinked at the enormous sums mentioned, for the notion carried unanimously. And just before the meeting ended, Truitt Davis announced that Percy Sutton, the well-known New York politician (and a native Texan), who was sitting in on the proceedings, “is considering the possibility of becoming a director of the Corporation.”

A month after that meeting in London, CPI’s first full year as a major company came to a close (CPI’s fiscal years ran from June to June) with the company recording more than $600 million in revenues. The subsequent fiscal year was CPI’s great moment in the sun. That was the year the company reached $870 million in revenues; the year it issued a small but successful offering of stock; the year it branched out into hydroelectric power and expanded the scope of its operations until they stretched from Corpus Christi to Salt Lake City to Redding, California, to Williston, Montana. That, in sum, was the year CPI built its empire. In June 1981, as the fiscal year drew to a close, the head of the drilling subsidiary said that he thought “the sky is the limit for this company.”

The truth was, though, that if you forgot about the boom for a moment, it was possible to see a few faint clouds in the sky. CPI’s profit margin was about $3 million—awfully small for a company with $870 million in revenues. The drilling company in particular hadn’t done well at all, making only $500,000 profit on revenues of $17 million. That wasn’t even close to what other companies of comparable size were making. And in January 1981 the government revoked the small-refiner bias, which had an immediate effect on CPI. In the fourth quarter of the fiscal year, the refinery, which had always been the company’s “cash cow,” lost close to $4 million.

More ominous than the numbers themselves was what lay behind them. For instance, Young and Davis hadn’t even known about the drilling company’s troubles until they saw the year-end books. The new head of Tierra Drilling (John Jacobs had left after a falling-out with Truitt Davis) had never bothered to tell them, and they had been too busy to ask. Their belief that they should allow their managers the freedom to manage worked against them during the boom: the company was growing too fast for them to keep track of everything that was going on. The result was that individual division heads would undertake new expansion programs or make decisions involving millions of dollars, and Young and Davis would find out about them only after the projects were already under way. The company was slipping out of their grasp.

Young says now that he saw it happening. But if that’s so, he never knew what, exactly, to do about it. When he complained to his division heads, they were always quick to reassure him that they had done the right thing, and he usually accepted that. When he complained to Davis, he found his partner largely unsympathetic to the problems that came with managing his companies. Davis was still interested in starting new ventures, but he thought it was Young’s responsibility, as president, to get the company under control. Here was exposed the fatal flaw in their partnership: Truitt Davis was unwilling to take control, and Jack Young unable.

And, too, the people running CPI—including Young—were often too busy tasting the executive life to spend much time dwelling on potential problems back in the oil patch. The fact was, running an oil company during the boom was fun. Young recalls that the reason he was never too concerned about the loss of the small-refiner bias was that he was just then traveling the country, trying to interest analysts in the stock issue CPI was going to offer. The agenda for that road show, which was set up by CPI’s investment bankers, displays a decided preference for doing things first-class. Young and the other CPI executives traveling with him went not just to Dallas and Houston and New York but also to L.A., San Francisco, Paris, and London. Whenever possible, they traveled in their own private jet. (CPI owned two corporate planes at one point.) They held private luncheons at places like the Mansion in Dallas and the exclusive Bistro in Beverly Hills, and they stayed in hotels like the Crillon, perhaps the most expensive hotel in Paris, and the Inn on the Park in London. That’s the way major corporate executives did business, and in their own minds at least, that was what CPI’s executives had become. Living the life was part of the dream too.

The Boom Busts

Nothing CPI did in its brief history better epitomizes the general sense of euphoria during the boom than the formation of one subsidiary in particular: Tierra Petroleum. In retrospect, no single subsidiary better illustrates why CPI failed. Tierra Petroleum was CPI’s exploration and production arm. A great deal of money was invested in Tierra Petroleum, and more than that, a great deal of hope. Tierra, it was thought, would someday be CPI’s anchor, the subsidiary that would eventually produce the kind of income needed to ensure the parent’s success in hard times as well as boom times.

It was created in January 1980, and in CPI’s one and only annual report, issued in mid-1981, much space was devoted to a chest-thumping appraisal of Tierra’s prospects. CPI announced that it had spent $16 million getting Tierra Petroleum off the ground and that the new company had already bought 122,000 acres. Tierra’s head, a veteran oilman named Alan C. Ambler, had visions of drilling up to sixty wells in 1982 and spending $40 million to $50 million on exploration.

For a company the size of Tierra Petroleum, that was a staggeringly ambitious drilling program. Sixty wells? Ten was more the norm for a new company. But then, Tierra’s big plans didn’t make it any different from anyone else in the oil patch. During the boom, the question more often was, Why not sixty wells? Why not $40 million? Al Ambler would find out soon enough why not—but alas, in this, too, he was no different from everyone else in the oil business.

Ambler’s main qualification for running Tierra Petroleum was that he was Jack Young’s friend. They had been neighbors back in the days when Young was a dentist, and after Ambler moved to Denver in the early seventies they had remained in touch. Ambler’s reputation in the oil patch was solid, but he had never run a company of anywhere near the dimensions that were envisioned for Tierra Petroleum. In Denver he had set up a five-person oil consulting company called Pagasco Services, which did well but had never really cashed in on the oil boom in any substantial way. So when Jack Young called him in 1979, Ambler jumped.

Young and Davis gave Ambler a large block of CPI stock (450,000 shares) and a contract guaranteeing him a base pay of $70,000 a year but containing enough bonus clauses to ensure that his real salary would be much, much higher. (His 1981 salary was more than $178,000.) But what Ambler got most of all was promises, the chief of which was that he wouldn’t have to worry much about raising money. He would be given free rein to build the kind of exploration company he had always dreamed of, and CPI would back him to the hilt. Indeed, as Ambler remembers it, when he made his first presentation to Davis and Young, Davis complained that it wasn’t ambitious enough. Ambler’s plan called for spending about $3 million. “By the end of the year,” he wrote in an early report, “it is conceivable that we will need one landman, one additional engineer, and two additional geologists.” When Davis saw that report the first thing he said was, “I want you to challenge us—see how much money we can raise. What kind of company could you build with forty million dollars?” Young says now that he was stunned by that figure—he, after all, was the “us” who would be raising the money—but he swallowed hard and said nothing.

What Ambler could build with $40 million, actually, was quite a bit. For openers, he could set up four field offices instead of just one, which he promptly did. And he could begin filling those offices with a lot more than a few extra geologists. In the midst of the boom, hiring was a particularly expensive undertaking. Ambler was able to lure from the Texas Oil & Gas Company of Dallas an old friend named John Morrison to be his second in command. But to get Morrison, Ambler had to offer him a contract that pretty much assured him a salary of more than $100,000 and included royalty interests in Tierra prospects. Had Tierra Petroleum ever really made it, this contract would have made Morrison a millionaire. Morrison in turn promptly began raiding Texas Oil & Gas for all the good explorationists he could persuade to jump ship. They, too, received generous contracts. There were also perquisites: boom-time explorationists had become accustomed to working in plush offices, so Ambler made sure his offices had all the right touches—the big desks, the cushy armchairs, the expensive rugs.

Within a year an impressively large organization had been put in place. In June 1980 Tierra had six employees and was paying $175,000 a year in salaries; by June 1981 it had 56 employees and $1.4 million in salaries. The total overhead, which in 1980 had been about $28,000 a month, was closer to $150,000 a month in 1981. But overhead and salaries were only a small part of what it cost to run a boom-time exploration company. The real money was spent on things like acreage, which in some hot plays cost $200 an acre instead of $50; drilling the wells, the cost of which had risen dramatically, and even the cost of money itself (interest at that time was running around 22 percent). To pay for all of this, Young and Davis had to dig deep into CPI’s pockets. Income from the Calcasieu Refinery and other profitable subsidiaries was plowed into Tierra Petroleum. CPI also went to Continental Illinois and Abilene National and borrowed about $8 million for the subsidiary. In just two years—roughly the time it took for Tierra to rise and fall—CPI invested $20 million in it.

On paper just about every move Tierra Petroleum made was defensible. The decision to open four offices instead of one, to cite an example, made sense because Tierra’s exploration program was centered around those four areas. Ambler reasoned—correctly—that the closer he was to the action, the better his chances were of getting a piece of it. So what went wrong? The former CPI explorationists I talked to all had the same answer: they ran out of time. “You don’t build an exploration program overnight,” one of them said. “It takes years if you’re going to do it right. We had some great prospects. We just ran out of money before we could drill them.”

Maybe. But maybe not. For underlying Tierra’s strategies were assumptions that in many ways typified the boom mentality. One assumption, of course, was that the CPI money would never dry up. Another was that Tierra’s explorationists would be good enough, or lucky enough, to beat the odds. Even average success would not have been enough to keep Tierra going, so wildly inflated were its projections. The last assumption, and the most misguided, was that the price of oil would keep going up. So what if it cost $200 to lease acreage? Who cared if you had to give explorationists exorbitant contracts? As long as the price of oil kept rising, it didn’t matter. It was covered.

The first inkling of trouble—it is much more obvious now than it was at the time—came fairly early. In April 1980 Tierra put together a limited partnership that raised $3 million. It was a pretty easy deal. In 1980 there were people all over the country looking to invest in limited partnerships with an oil company. But the partnership was a bust; the wells drilled with the money were either marginal producers or dry holes. The people at Tierra wrote it off to bad luck. In December the company raised another $3 million the same way. Again the drilling program was a flop; again no one was overly concerned. It just seemed like one of those things that happen in the oil business. They’d do better next time. That month the rig count reached 3,400.

The following month was when the federal government abolished the small-refiner bias, and the cash from the Calcasieu Refinery stopped flowing to Tierra. But Ambler wasn’t too worried; Young told him CPI could still raise all the money he needed. And everyone at CPI assured him that the refinery could survive the loss of the bias, so in the back of his mind was the thought that eventually Calcasieu might again be a source of income for Tierra Petroleum. Ambler kept building the company.

In March 1981 CPI raised $10 million in a stock offering. Most of that money went directly to Tierra, and Ambler used it to buy acreage. In May the rig count hit 3,800, and the following month CPI issued the annual report, in which Ambler predicted a $40 million drilling program. “By early 1982,” he said, “I expect our cash flow will cover our monthly overhead costs. . . there’s no reason we shouldn’t be a strong cash flow contributor to CPI within 12 to 18 months.”

But there were reasons—two in particular—and that summer, even though the boom was still in full swing, Tierra’s problems began to catch up with it. The first problem was that CPI’s supply of money wasn’t limitless after all. A $40 million drilling program needed, well, $40 million, but where was it going to come from? Not from the refinery; that was shut off. And not from other subsidiary profits either, since those profits weren’t all that large to begin with.

In an attempt to solve the growing cash dilemma, Tierra decided to raise some money by putting together another limited partnership. To that end it enlisted the aid of the investment banking house of Smith Barney Harris Upham & Company. For months the people at CPI and Smith Barney worked on the deal, and it looked like a cinch. Smith Barney assured CPI that it could raise $11 million. Tierra Petroleum, suddenly in dire need of cash, spent about $3 million in anticipation of that payday from Smith Barney. But the payday never came. At the last possible moment, after the money had already been lined up, Smith Barney pulled the plug on the deal, causing the limited partnership to fall apart. The investment bankers wouldn’t say why they did it (they still won’t), but the rumor was that they had been scared off by a Department of Energy investigation of some of CPI’s crude buying deals. (There was an investigation, but nothing ever came of it.)

Now Tierra had lost two sources of capital—the refinery and the equity market. And that made the chances of getting more money from the bank extremely unlikely. The situation was serious, and Al Ambler knew it. With a smaller operation he might have been all right. But he had $16 million worth of acreage up and down the oil patch. He had sixty prospects waiting to be drilled. He had 22 percent interest to pay. He had all that overhead and all those salaries to worry about. And he didn’t know where he was going to get the money to pay for everything.

There was always another potential source of income for Tierra Petroleum, of course, and that was income from its own producing wells. But that prospect bumped up against the company’s second lingering problem: its luck in the oil field was terrible. Former Tierra geologists insist that their ratio of hits to misses was about average for the industry. But their hits were mostly marginal wells and their misses were sometimes very costly. From the days of the first limited partnership, Tierra Petroleum was never able to bring in that one big well that could have put the company over the edge.

For instance, the same summer that the Smith Barney deal fell through, Al Ambler played one of his biggest exploration cards. Up in the Dakotas there was a very hot gas play, the sort of play where every day would bring news of another huge well. There was clearly a big gas field there, and lo and behold, Tierra already owned land in the play. Tierra’s landmen raced to the Dakotas and quickly snapped up some more acreage. This could be it, they thought; this could be the acreage that would make everything right again. They would be drilling a wildcat well, to be sure, but nonetheless they thought they had a winner. The geologists chose the site of that well with great care, and about $1.2 million was poured into drilling it. And it was a dry hole. Another bitter pill. The company lost faith in the acreage, and rather than drill another well it sold the Dakota leases.

By the end of the summer, even though the boom was still on and the rig count still rising, Jack Young and Truitt Davis had to be discouraged when they looked at Tierra’s balance sheet. Despite a $20 million investment in the subsidiary, Tierra was producing only $100,000 a month in oil and gas revenues. That wasn’t even enough to cover the overhead. In late summer, with the rig count at more than four thousand, Al Ambler reluctantly took the first step toward dismantling the organization he had so enthusiastically built. He closed down the Oklahoma City office.

The Unaudited 10-K Report and Other Disasters

As winter approached, Young and Davis decided that the only way to recoup their investment in Tierra Petroleum was to sell it outright. The decision made a lot of sense: Tierra was fast becoming a major disaster. The timing looked good too. In December 1981 the rig count hit 4,530. But what they didn’t know—couldn’t know—was that that was as high as the rig count was going to get. The oil boom was ending.

It was hard to see that at first, even when the rig count began to drop. In early 1982 CPI got several nibbles from other oil companies, still caught up in boom fever, about buying Tierra. Among them was a large independent oil company named Nucorp Energy, based in San Diego, for whom the good times had been very good indeed. Nucorp had used the boom to accumulate more than $500 million in assets, and what it saw in Tierra Petroleum was a chance to take advantage of someone else’s boom-time mistakes. The initial asking price for Tierra was $50 million, enough to pay off all of CPI’s long-term bank debt (about $32 million) with plenty left over to shore up the rest of the company. The two sides finally settled on $37 million. When Nucorp went to its bank to get the money, however, it found that its own mistakes were catching up with it. With the rig count falling now—it dropped to 4,300 in January—Nucorp couldn’t raise the money and was forced to back out of the deal. Six months later Nucorp declared bankruptcy, and at the end of 1982 it reported $412 million in losses.

For Tierra it was over. In February, with the rig count at 4,000, Ambler closed down his Denver and Corpus Christi offices and laid off most of the staff there. The remaining staff tried desperately to sell off acreage to stay alive—the company had done so successfully during the boom—but this time no one was buying. Even with the reduced overhead, Tierra was having an increasingly difficult time paying its bank debt. In March Truitt Davis resigned as CPI’s chairman of the board (though he remained a board member). As CPI’s problems had grown, Davis’s relationship with others in the company had become increasingly strained. He thought the division heads were the source of the company’s troubles; they thought he was to blame. His parting was not mourned by either side. In May Al Ambler resigned. That month the rig count dropped to 2,930.

It was in free-fall. It was now the spring of 1982, and CPI’s problems had spread far beyond Tierra Petroleum. All over the oil patch the realization was taking hold that the boom had turned to bust. And everywhere Jack Young looked he could see the roof falling in. What had once been little leaks had turned into a deluge. Dunnam Tool & Supply, which had been such a nice little profit center just a year before, was starved for cash. A lot of its customers who had bought on credit could no longer pay their bills, which meant that Dunnam couldn’t pay the money it owed. When the company finally closed its doom, it had on its books more than $500,000 in uncollected—and in many cases uncollectable—bills.

Meanwhile, the drilling company’s business was drying up. With the natural gas market extinct, the deep rigs owned by Tierra Drilling became dinosaurs. One by one those rigs came off drilling projects only to find that there was no new work. Gradually, agonizingly, the drilling company’s revenues slowed to a trickle; by June 1982 only one of the company’s fifteen rigs was still working.

Jack Young and Mack Fowler—who had become CPI’s chief operating officer in March—did what they could to salvage what was left of the company: they discontinued seven CPI subsidiaries and sold an eighth to the people who had been running it. They cut the number of employees from 900 to 150. They found a buyer for all that pumping service equipment Truitt Davis had bought, but the buyer backed out on the deal at the last second. It was too little too late. Near the end of the summer the New York Times printed a small item in its business section that said that CPI’s “contract drilling unit has defaulted on certain payments due under its loan agreements.” A few months later the Times ran another short item on CPI. “Consolidated Petroleum Industries, Inc.,” said the Times, “reports that it has not filed its form 10-K report with the SEC . . . because it has laid off its accountants and cannot afford an outside auditor.” The unaudited 10-K the company eventually prepared showed that it had lost $20 million in fiscal 1982 and that its total bank debt was around $25 million.

On August 1, with the rig count at about 2,600, Truitt Davis severed all his connections to CPI. Five days later Jack Young resigned as president of CPI, although he remained on the board. Young persuaded Mack Fowler to take his place as president. Thus was Fowler given the unenviable task of, as he likes to put it, “grabbing the stick and landing the thing.” Which is what he’s been doing ever since.

$500 Miscellaneous? What’s That For?

Today CPI’s main office is not in Midland or Abilene but Houston, in one of those unpretentious low-slung office buildings off Post Oak Road near Westheimer. Fowler had always operated out of Houston, and when he took over the company one of the first things he did was move it there. CPI has 13 employees working out of the Houston office (and 41 altogether), and you can still see in that office, just as in the CPI yard in Midland, some of the relics of the past. Several rooms are filled with rows of cabinets containing files from the old days, and here and there expensive computer equipment sits unused. Some parts of the company are still operating: Davis’s hydroelectric plant is in business, as is the refinery. One rig remains in use. Royalty arrangements Tierra Petroleum negotiated in days gone by also bring in some revenue. In all, CPI takes in about $100 million a year—mostly from the refinery—but it’s not making a profit; indeed, it can’t even afford to pay off the interest on its debt. One thing CPI has not done is file for bankruptcy, but then, there isn’t much point to it. If the banks decided to foreclose on the company, they would be the ones stuck with the company’s equipment and its uncollected receivables. The way matters stand now, CPI is responsible for keeping up the equipment and selling what it can, and going after whatever money it can get from what’s owed it. As long as the bust lasts, the banks are willing to wait for what’s theirs. On the other hand, they don’t really have much choice, given what the bust has done to the value of their collateral.

Fowler spends a lot of his time these days in a kind of hand-holding operation; he makes sure that everyone who has a stake in CPI—the banks, the creditors, the stockholders—knows what the company is up to. When he can collect a receivable or make a payment to the bank, he does so. He keeps the SEC up-to-date. The rest of the time he makes sure that he knows what is happening in every little corner of the company. One day I watched him going over the monthly budget with his Midland staff. There was no line item small enough, no detail insignificant enough to escape his attention. That $500 listed under “Miscellaneous”—what was that for? Did it make sense to take out the phone system and replace it with the phones gathering dust in the hangar? Would that save any money? How much was it going to cost to lease part of Ike Lovelady’s yard to stack some rigs? (The answer was $400 a month.) It was an impressive performance, but a sad one too, for watching these men haggle over such piddling sums made you realize just how far CPI had fallen from the days of that London board meeting when $40 million in expenditures was approved after a few moments’ deliberation. But the truth is, CPI is a much better-run company in its current skeletal condition than it ever was in its heyday.

Fowler’s best-case scenario has CPI coming out of the oil bust a smaller but smarter company. He’s probably being optimistic, but it is certainly within the realm of possibility. CPI has enough equipment in good enough condition that it could get back into the drilling business. The refinery is fairly new, and it could be revved up again. But the first and most important requirement for a CPI revival is better times in the oil patch, and with the rig count still falling—it was at 1,860 as of April—no one is counting on that any time soon.

Truitt Davis is completely out of CPI now except as a holder of a large amount of near-worthless CPI stock. Jack Young is still on the board (as is Frank Ikard), and while he frequently talks to Fowler about CPI, it is Fowler’s company now. And in any case, Young and Davis have enough problems of their own without worrying about CPI. Both men have sizable debts with the Abilene National Bank, some of which are the result of loans they took out to buy stock in Don Earney’s banks. Davis, who once owned 6 percent of the Abilene National Bank, now owes that bank more than $1 million. Young’s debt is nowhere near that large, and he seems to be working things out satisfactorily with the bank.

Jack Young still thinks of himself as an oilman. He vows that he won’t return to dentistry, and he hasn’t; instead, he spends his days trying to put together deals that will get him back in the oil patch. Despite everything that’s happened, he is still on friendly terms with most of the people who worked for him at CPI. Young is much chastened by what happened at CPI, of course, but the last time I saw him he made a point of telling me that the oil business was still, in his opinion, “the greatest business there is. You’re going to have busts,” he said with a sad smile. “And then you’re going to have booms again. That’s the way the oil business is.”

He’s probably right about that. And when the next boom comes, people will jump in with both feet, much as they did during the boom just past, looking for a quick killing. They’ll try to make their companies grow a little too fast and their financing stretch a little too far. They’ll get greedy, and they’ll gamble that the boom will never end. And when it’s all over, some of them will be rich, but many others will have joined Jack Young among the could-have-beens. That’s the way the oil business is too.