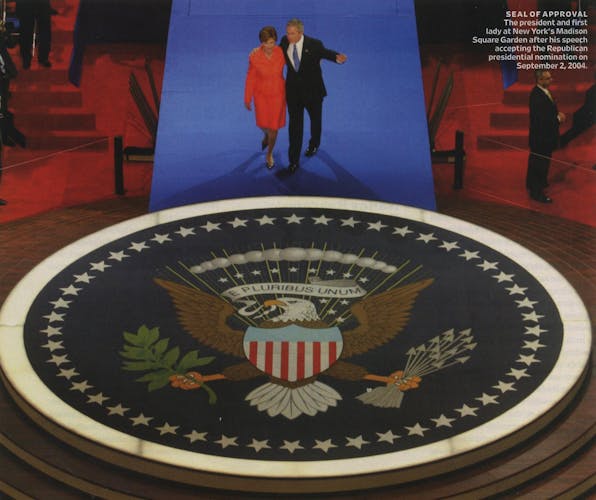

WITH JUST DAYS TO GO before the end of this, one of the bitterest electoral seasons in memory, I found myself wondering how Laura Bush, that famously reluctant political wife, was holding up. She seemed to be doing just fine: Resplendent in powder blue, she sent the Republicans into a frenzy during her impeccably soporific speech at the GOP convention, and she was even nice to Dr. Phil after he noted crabbily on a promotional spot that first twin Jenna Bush had stuck her tongue out at reporters. Laura seemed to have long forgiven—or was using to ironic effect—her husband’s broken promise several decades ago that she would never have to make a political speech. Now she was barnstorming the country on George W. Bush’s behalf, speaking her mind—albeit softly—being less than optimistic about the prospects for stem cell research, supporting those smarmy Swift boat ads that denigrated John Kerry’s military service, and being nasty-nice as the First Surrogate, calling Rathergate as she saw it. (“You know,” she said of the 60 Minutes documents that purported to prove her husband was a military slacker, “they probably are altered and they probably are forgeries, and I think that’s terrible, really.”)

Her sable-hued, wash ’n’ go do remained impervious to attacks that others might consider hair-raising. Loyal Democrats have taken to spackling her with the Stepford Wife label. Cultural critic James Wolcott, swept up in an anti-Bush swivet, retracted the nice things he had said about Laura in Vanity Fair and dissed her in his blog as “just another warden in a pantsuit” and “another saccharine phony.” Kitty Kelley described her in The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty as the Southern Methodist University coed who was “the go-to girl for dime bags of marijuana.” In The Perfect Wife, biographer Ann Gerhart dumped all over her for being a bad mom. (“There is plenty that the Bushes don’t ask their daughters to do, that much is clear.”) Austin artists and writers—big fans when Laura was their ardent supporter as Texas’s first lady—have raised money to display their unhappiness with the president in full-page newspaper ads in swing states. Prestigious American poets torpedoed a reading she tried to host at the White House. Laura Bush has sailed through all this and more, without once asking anyone to “shove it.” This may be why John Kerry praised her, rather wistfully, I thought, in the first presidential debate as a “terrific person” and “a great first lady.”

Indeed, Laura has mastered the cleverest first ladies’ trick of becoming more popular than their more famous spouses. Even better—for herself and her husband—Laura’s ascendancy has occurred at a time when the women’s vote, lost by Bush-Cheney in 2000, appears to be up for grabs. Noting the first lady’s “Xanax-like demeanor” and “faultless librarian’s poise,” überfeminist and Gore 2000 adviser Naomi Wolf conceded that the Bush team has brilliantly closed the gender gap by putting Laura, Condoleezza Rice, Lynne Cheney, and other goody-goody GOP goddesses out front, in stark contrast to Teresa Heinz Kerry, whom Republicans like to portray as Ms. Tabasco and Onions (even though Mrs. Cheney could easily compete for the title). Laura’s fans and critics alike tend to see her enormous popularity as either a reaction to her pushy predecessor or to her own husband, who can inspire paranoid psychosis in his detractors with just one well-timed smirk. Or they credit Laura’s success—she couldn’t possibly do it alone!—to the stark, deadly efficiency of Team Bush, particularly the recently returned Iron Maiden, Karen Hughes. All of these political assists may indeed have helped the first lady become nearly as popular as her stiletto-shrewd mother-in-law, but it is time to give credit where credit is due. Laura Bush is probably our most brilliant first lady to date, because she understands the kind of woman the American public really wants as its representative and role model: a complete and total cipher. She has intentionally made herself into a blank screen upon which they can project their own ideas about womanhood.

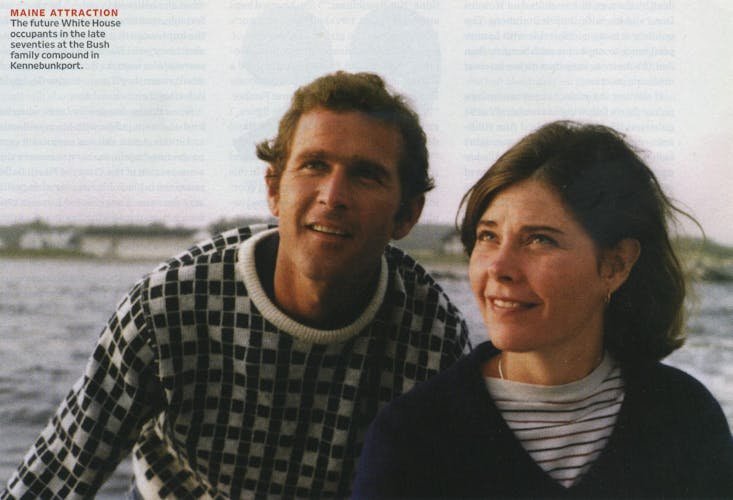

CONSIDER THE EVIDENCE. Unlike a great many political wives—Nancy Reagan, Rosalynn Carter, and Hillary Clinton come to mind—Laura Bush knew what the job entailed and early on declared her indifference. Friends Jan and Joe O’Neill had to campaign for two years before she would agree to meet George W. Bush, and even then, the man Laura eventually married wasn’t exactly wearing a sandwich board that said “Future President of the USA” or even “Future City Councilman.” Bush then was just a good-time Midland oilman, something of a galoot. (Note to Freudians: Laura’s father was known for his exuberance; he was the kind of guy who broke into “Hello, Dolly!” when Laura’s blond friends walked in the door.) Assuming George’s wells would have eventually come in—and, given his history, that’s a big assumption, but something else might have come along—Laura probably envisioned a future as a Midland society matron, not a role to which all ambitious career women aspire but a cushy, cozy life nevertheless. (Biographers tend to focus on the hot, dry, dusty landscape of Midland—“an innocent life of burgers at Agnes’ drive-in and of cruising the flat, windswept streets of West Texas,” said the Washington Post—overlooking that many of the city’s community leaders were wealthy Eastern transplants like her suitor’s parents, who brought the manners and mores of the American aristocracy with them.) It was, and is, on the surface at least, an urban oasis of book clubs, garden clubs, country clubs, and the kind of strange rites that spring up in isolated wealthy communities. In other words, Laura wasn’t the kind of wife who staked her well-being on her husband’s success in the world; if George could have made himself into an even semi-successful citizen of Midland, she probably would have been content to raise her children in her hometown, reading, carpooling, visiting with her parents, and taking the occasional trip on somebody’s private jet.

CONSIDER THE EVIDENCE. Unlike a great many political wives—Nancy Reagan, Rosalynn Carter, and Hillary Clinton come to mind—Laura Bush knew what the job entailed and early on declared her indifference. Friends Jan and Joe O’Neill had to campaign for two years before she would agree to meet George W. Bush, and even then, the man Laura eventually married wasn’t exactly wearing a sandwich board that said “Future President of the USA” or even “Future City Councilman.” Bush then was just a good-time Midland oilman, something of a galoot. (Note to Freudians: Laura’s father was known for his exuberance; he was the kind of guy who broke into “Hello, Dolly!” when Laura’s blond friends walked in the door.) Assuming George’s wells would have eventually come in—and, given his history, that’s a big assumption, but something else might have come along—Laura probably envisioned a future as a Midland society matron, not a role to which all ambitious career women aspire but a cushy, cozy life nevertheless. (Biographers tend to focus on the hot, dry, dusty landscape of Midland—“an innocent life of burgers at Agnes’ drive-in and of cruising the flat, windswept streets of West Texas,” said the Washington Post—overlooking that many of the city’s community leaders were wealthy Eastern transplants like her suitor’s parents, who brought the manners and mores of the American aristocracy with them.) It was, and is, on the surface at least, an urban oasis of book clubs, garden clubs, country clubs, and the kind of strange rites that spring up in isolated wealthy communities. In other words, Laura wasn’t the kind of wife who staked her well-being on her husband’s success in the world; if George could have made himself into an even semi-successful citizen of Midland, she probably would have been content to raise her children in her hometown, reading, carpooling, visiting with her parents, and taking the occasional trip on somebody’s private jet.

Not that Midland was dull. “In Midland, you have to make your own fun,” a former resident explained to me. The newlyweds, for instance, attended a party in which smashing Waterford crystal goblets on the edge of a swimming pool passed for entertainment, as did a dirty T-shirt contest for which the Bushes arrived wearing complementary ensembles that read “I love Bush’s thingie” and “I love Bushy things.”

Once the couple moved to Dallas, where in 1987 Bush found gainful employment as the managing general partner of the Texas Rangers, George and Laura’s lives were somewhat more refined but no less comfortable. They nestled into prosperous, leafy Preston Hollow, stayed focused on their much-wanted twins, and showed up at the baseball stadium whenever time permitted, which was often. (He liked to autograph baseballs for visitors between innings, a sign, perhaps, that he had his eye on bigger things.) Laura lived as she always had, surrounded by close friends and raising the girls. So when her husband voiced his ambitions to run for governor in the early nineties, it made perfect sense that Laura would be reluctant to go along. She had loved campaigning with him when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, in 1978—she had him all to herself—but the comforts of North Dallas life and the demands of motherhood (and, most likely, a few more years as part of the extended Bush clan) had made her averse to the role of political wife. In exchange for her blessing, George promised that he “would never make her do anything” in support of his political career—unless, of course, she wanted to. (This was the same deal, by the way, that backfired on Howard Dean and his wife, Judith Steinberg. The public was more comfortable with Laura’s preference to stay home with her girls than Judith’s desire to keep up with her internal medicine practice.)

If she was ambivalent about becoming a public figure following her husband’s 1994 gubernatorial victory against Ann Richards—maybe, like a lot of people, Laura didn’t believe it would happen—she adapted, in her own way, to life in the capital. The cadre of studiously underdressed Austin Democratic women who worried that she would impose Escada suits and flashy Dallas jewelry on the populace was immensely relieved when she showed a preference for slacks, rubber-soled shoes, and liberals. (Many of Laura’s oldest friends were progressive Austin Dems; wealthy progressives, but progressives nevertheless. “If you were to characterize them,” clarified one Austin social observer, “you’d think ‘Not Republican.’”) She haunted local antiques shops, tweaked the Governor’s Mansion, put the girls in public school, stayed late at parties long after her teetotaling husband left for bed—and started a statewide book festival with her (seriously Democratic) friend Mary Margaret Farabee. “Well, if I’m going to be a public figure, I might as well do what I’ve always liked doing,” Laura told a reporter at the time. “Which means acting like a librarian and getting people interested in reading.” In this way the first lady of Texas became an enormous asset to the image of intellectual sophistication Texas was trying to present to the world and the era of good feeling that prevailed in the Capitol. (Bob Bullock was George W. Bush’s mentor then, and Karl Rove was just a political consultant.) While the Republican governor was stressing bipartisanship, it didn’t hurt that his wife seemed to be a closet lefty. Laura rarely said what she believed in public, but her comfortable, contained silence left people with the impression that she agreed with . . . just about everyone. He couldn’t be all bad if she married him went the thinking among those who’d sworn they’d never forgive George for defeating their beloved Ann.

Some things changed for Laura when her husband went public with his presidential ambitions. Again, she was a reluctant campaigner, and again, we have to assume that some version of the Treaty of North Dallas remained in place, but not everything could stay the same. I interviewed Laura in 1998 for a national magazine, hoping she might help me explain Bush to the rest of the country, who thought of him only as George Junior. There was construction around the front of the Governor’s Mansion that sunny winter morning, so Laura greeted me warmly at a back door, as if I were a new neighbor she’d heard nice things about. But the slacks and rubber-soled shoes had already been replaced by sensible pumps and a nice Republican suit, the jewel tone of choice being purple, I recall. Her gaze, from those preternaturally turquoise eyes, was friendly but assessing. We warmed up with small talk about the mansion’s fabrics and furniture. Her voice remained soft and animated when she complimented me on a story I’d written, notable then and in retrospect because it was about a gay marriage. (“Good politics!” I thought at the time.)

But when we settled in for the interview, Laura sat ramrod straight, sometimes folding her hands neatly in her lap, sometimes folding her arms across her chest in classic you-are-the-enemy-now posture. (She reminded me a little of Ann Richards then, never a fan of the press.) The casual woman who liked to steal out of the mansion for long walks and cheer her daughters’ friends at high school baseball games had already been packed up for storage. On the topic of George W. Bush—her involvement with his retreat from alcohol in 1986, her desire to help him be “a uniter, not a divider”—she was careful and controlled, her efficient smile slipping every once in a while into a small grimace. That was all I was going to get: a few well-chosen, non-revealing statements. The Buddhists warn that unhappiness can come from attachments, and Laura Bush wasn’t holding fast to her happy life as the governor’s wife; she was moving on. I was the one stuck in the past, expecting the person she’d been.

It was this ability to move forward with the steady, steely assurance of a Coast Guard cutter that seems to have confounded the national press when she arrived in Washington. They wanted to know her; she didn’t want them to. She was perfectly happy to let them think she was bland or dull; she wasn’t going to expend her energy changing their minds. (At one point, slightly annoyed by her press, she told a reporter that she wasn’t shy; she was introverted, a sorority girl’s delicate way of saying she’d rather be alone than with members of the media.) The press tried to retaliate. Laura’s varied life as an academic (the master’s in library science), a teacher of poor kids for nearly a decade, a stay-at-home mom, and a devoted wife was portrayed not as a paradigm of feminist flexibility but as an example of a woman whose myriad choices ultimately meant nothing, except that every choice she had made could be used to advance her husband’s career. “She is the Play-Doh first lady,” wrote The New Republic in August 2001. “Mold her into whatever shape you want, then stamp her back down into a pile of putty for her next audience.” The author added that when Laura lunched with Hillary Clinton as the latter was leaving the White House, the new first lady wore “a terrible purple plaid number, looking like nothing so much as a country mouse.” She could not possibly be smart: That she was an insatiable reader was met with incredulity, particularly when she cited an imposing chapter in The Brothers Karamazov as her favorite part of her favorite novel. Wrote the author: “Asked about this ambiguous and unsettling passage—in which Christ returns to earth only to be arrested as a heretic and threatened with burning at the stake—Laura replied bafflingly, ‘It’s about life, and it’s about death, and it’s about Christ. I find it really reassuring.’” It’s only baffling, of course, if you refuse to take Laura at her word, but the first lady plainly didn’t care what the journalist thought. She later joked about donating her plaid suit to a historical clothing collection and to this day keeps The Brothers Karamazov on her White House Web site reading list.

“If I differ with my husband, I’m not going to tell you about it,” Laura told a reporter in 2000, which, as it turns out, was the last word on her intention to maintain a zone of privacy around her feelings and opinions. It was the Austin technique writ large: The less she said, the more the public seemed to project its own feelings onto her, and most of those feelings were helped along by the kind of harmless and heartwarming appearances no one could carp about. Laura was in favor of reading (good!), she was against heart disease in women (great!), she never changed her hairstyle (a relief), and she had absolutely no intention of participating in a co-presidency (ditto). The idea of using the first lady’s job as a bully pulpit didn’t suit her solitary, self-effacing temperament, and it didn’t suit the times, which even before September 11 were rancorous enough without throwing a Hillary-type into the mix.

Instead, Laura told reporters that Lady Bird Johnson was her White House model, which satisfied just about everyone. Both women were gracious; both women showed a knack for handling cantankerous men; both women knew how to keep out of trouble. But Laura also had a pinch of Jackie in her sly wit and passion for the arts—soon enough, no one could mistake her for a cowgirl. She also had more than a little in common with Bess Truman, who retreated to Independence, Missouri, for months at a time because she hated “the rigmarole” of Washington. Austinites got used to seeing the first lady sipping margaritas with friends at Manuel’s while her husband flew solo in Washington; people in Midland got a charge out of seeing an official government plane on the airport tarmac when Laura got a hankering to visit her mom. George opted for the White House; Laura opted to redo the house in Crawford.

Her biographers struggled mightily to add drama and pathos to a life that was, with a few exceptions, supremely happy and serenely uneventful. (Reading these accounts, you cannot help longing for a chronicler like Virginia Woolf, who knew how to endow seemingly ordinary people with rich internal lives, or Larry McMurtry, who understands the unshakable reserve of West Texas women.) At least three biographies have been written about Laura—three and a half, if you count her share of George and Laura, by Christopher Andersen—and in all, the reader comes out knowing almost less about her at the end than at the beginning. The same stories are recycled endlessly, with little to no elaboration from her. Hence, the repercussions of a horrible automobile accident in which she ran a stop sign and killed a close high school friend are used to explain variously her passion for order, the arranging of her bookcases according to the Dewey decimal system, and the sponging down of homes with Clorox; the climactic moment in which she persuaded her husband to stop drinking is used to show her inner fortitude and profound influence (even though she’s denied that she ever spoke up in such a manner). Laura went from being the cowed librarian to her hot-tempered husband’s personal Prozac; she alone could control him with words like “Rein it in, Bubba,” according to the New York Times.

Then came September 11. Just as the events following that awful day proved to be her husband’s finest hours, they were Laura’s too, providing the perfect intersection of her personality and the nation’s needs. As biographer Gerhart put it, “The woman who had the capacity to lie for hours on a sofa, reading, was suddenly logging sixteen-hour days, and in full public view, perfectly groomed, suit pressed, hair in place, and always, waterproof mascara. . . . The same emotional clarity that had guided her in composing her life now informed a new mission.” She calmed, she comforted, she selected just the right hymns for the National Cathedral service, and she visited the site of the crash of Flight 93 in a lonely, muddy field in Pennsylvania. Just before George W. Bush’s 2002 State of the Union address, a USA Today/CNN/Gallup poll reported that Laura was the most admired woman in America. “I actually think that the American people think that the first lady ought to do whatever she wants to do,” she said.

It seems to have worked for her.

MANY CRITICS OF THE BUSH family want to believe that the current, more partisan incarnation of the first lady displays her obeisance to the family machine. (“She might as well be wrapped in veils,” one Democratic friend groused to me.) She took up for the entire clan when she bashed (in a nice way, of course) the Bush-snubbing Nancy Reagan over stem cell research. But Laura possessed many Bush-like tendencies before she ever became one; she blended so effortlessly into the family that her more progressive friends just failed to notice. She’s always been better at being a Bush—the idealized, admirable, loving family George H. W. and his wife, Barbara, concocted—than the Bushes themselves. Before she married, Laura devoted a decade or so to helping the kind of people her husband never showed much interest in until he decided to run for office. She taught school in poor communities, and though her husband performed brief volunteer work with underprivileged kids for a Houston organization called PULL in the early seventies, reporters have long wondered whether this was some form of mandated community service for goodness knows what. Laura’s reticence might be attributed to the fabled silences of West Texans, but it could easily pass for that of a musty but well-bred East Coast aristocrat, like the Connecticut Bushes. The pull of the past must have felt like an undertow to George when he met Laura; it’s no wonder the two married expeditiously, after a three-month courtship. Barbara Bush early on singled Laura out from among her daughters-in-law as the only one who was first-lady material. She was, by nature and preference, intent on staying out of the way: “I have the best wife for the line of work that I’m in,” the president once told a reporter. “She doesn’t try to steal the limelight.” (Or, as a mutual friend put it, “Bush didn’t have to marry his mother because he is his mother.”)

Laura didn’t crave attention like her ambitious in-laws, but that doesn’t mean she was a pushover. It was inconceivable that she would ever embarrass the family, as Jeb’s wife, Columba, did when she was fined for failing to declare jewelry and clothes she brought back into the U.S. several years ago, or try to outshine Barbara, as Neil’s wife, Sharon, did in the pre–Silverado scandal days in Denver and in her pre-divorce Houston society era. Still, Laura neatly deflected comparisons between herself and her mother-in-law (Lady Bird is my role model) just by being . . . herself. She was this way from the beginning: At the family compound in Maine, she avoided the Olympic trials that passed for family sporting events, staking out instead a spot on the front porch with her books and cigarettes. “What do you do?” George H. W. Bush’s famously competitive mother, Dorothy, asked Laura, when she was newly wed in 1977. “I read and I smoke,” Laura replied—Midlandese for “shove it.” The ever-watchful Barbara would later tidy up her daughter-in-law’s line in her 1994 memoir, claiming that Laura had actually said, “I read, I smoke, and I admire,” possibly grafting a few words from her own note to a Smith College alumni magazine. (“I play tennis, do volunteer work, and admire George Bush!”)

By keeping the family at some distance—and childhood friends close—Laura probably saved herself from the depressions suffered by political wives in general and Bush women in particular. Life in China was tough on Barbara Bush, by her own admission, as were the many times her husband left her, alone, to raise their ever-expanding brood. Laura, faced with a husband who wouldn’t own up to his drinking problem, threatened to walk when the situation became intolerable. (It isn’t just Kitty Kelley who suggested that Bush treated his wife like a doormat or worse when he was in his cups; people in Midland and in Washington, where George went to help his father on his 1988 campaign, saw the same short-tempered, dismissive oaf at social events.) Whether Laura was the person who directly intervened to get her husband to stop drinking or simply one of many who attempted to get Bush sober, she was soon characterized (by Bush himself) as the person who had “saved” him. She demurely denied doing any such thing, but the mythology grew when George faltered on the campaign trail during the 2000 race and Laura was supposedly the only person who could quiet him down. “She brought calm and serenity to his bearing,” spinmeister Mark McKinnon told this magazine in April 2001. “He was happier, more at ease, less distracted. Even on the airplane, he was more likely to relax. If she wasn’t there, he’d bounce around the plane.” Laura looked like a cavalry of one each time she made those sojourns to the front, and it never really occurred to anyone to ask why she hadn’t been there all along. Riding to the rescue boosted Laura’s popularity while it humanized her husband, a neat trick originally perfected by Lady Bird Johnson. In the passive-aggressive playbook, less is always more: The twins act out in public, and Laura explains that she never wanted them to feel oppressed by family pressures; meanwhile, she lets them get back at their dad for his absences in much the same way he exacted revenge on his own father.

Laura’s distaste for public life jibes perfectly with her husband’s propensity for privacy, though she wants to be alone because she likes being alone, and he likes being alone because he doesn’t like pesky, prying reporters. Either way, the result is the same: Laura has learned how to use the Bush machine to get what she needs. When Gerhart, who covered the first lady for the Washington Post, sent her a letter asking for her cooperation with a biography, Laura never responded. Word came from Karen Hughes, then a special adviser to George Bush, that it was “too soon” for such a book. Was it the cautious White House or the cautious first lady, or both, who had turned her down? Gerhart never knew. Since publication of that book, the vow of silence has extended even further from Laura’s center of gravity. After Gerhart criticized the behavior of the twins in The Perfect Wife, members of Laura’s Austin book club, who had been content to recycle the same pabulum on her behalf for years, decided to stay mum about their most famous participant.

Occasionally these loyalists can go too far in their self-imposed protectiveness, as when a group of Laura’s friends took over the Texas Book Festival (of which this magazine is a sponsor) this year and tried to institute a plan to ban political books, this being an election year and many of the books being less than complimentary about her husband. Thankfully, they reconsidered. But almost simultaneously, a rumor swept through Austin that Texas writers and artists who had signed a petition against the war—a petition that was to run as an ad in the New York Times if enough money was raised—would be banned from the book festival. This report also turned out to be false, but Laura’s friends weren’t shy about leaning on book festival participants who made their anti-war opinions public. “If I’d known my chicken dinner came with an oath of loyalty, I wouldn’t have eaten it,” said one of the petition signers.

But of course, it did. From her earliest days as a political wife, Laura has said that her first loyalty is to her husband, and nothing in her character has ever suggested that she would stray from that promise, despite separate vacations in Crawford. The pillow talk wished for by her Austin friends is a thing of the past, if it ever existed: When the first lady’s celebration of poetry threatened to collapse in a firestorm of rancor over the 2003 invasion of Iraq, she chose to have the event postponed indefinitely rather than embarrass the president. It’s a shame Laura didn’t believe, or wasn’t allowed to show, that she possessed the fortitude of Lady Bird, who famously—and politely—stood her ground when Eartha Kitt blamed her for her husband’s war at a White House women’s luncheon in 1967. Lady Bird listened while the singer harangued her—“I know the feeling of having a baby come out of my guts! I have a baby and then you send him off to war!”—then gathered herself and replied, “Because there is a war on, that doesn’t give us a free ticket not to try to work for better things—against crime in the streets and for better education and better health for our people.” Today, protesters are shouted down during the first lady’s speeches or, in the case of a New Jersey woman whose son was killed in Iraq, handcuffed and charged with trespassing.

Because of her reticence, Laura will probably never enjoy the same legacy as her mother-in-law or Lady Bird, both of whom found causes and pushed them with a passion that assured some sort of historical niche for themselves. But it’s likely that Laura Bush, who never aspired to the job in the first place, isn’t interested in any return other than a return to normalcy. The country is crazy and she’s standing still, waiting for the days when her life will again be occupied solely with friends and family. Maybe in these times, that’s just what the country needs.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Laura Bush

- George W. Bush