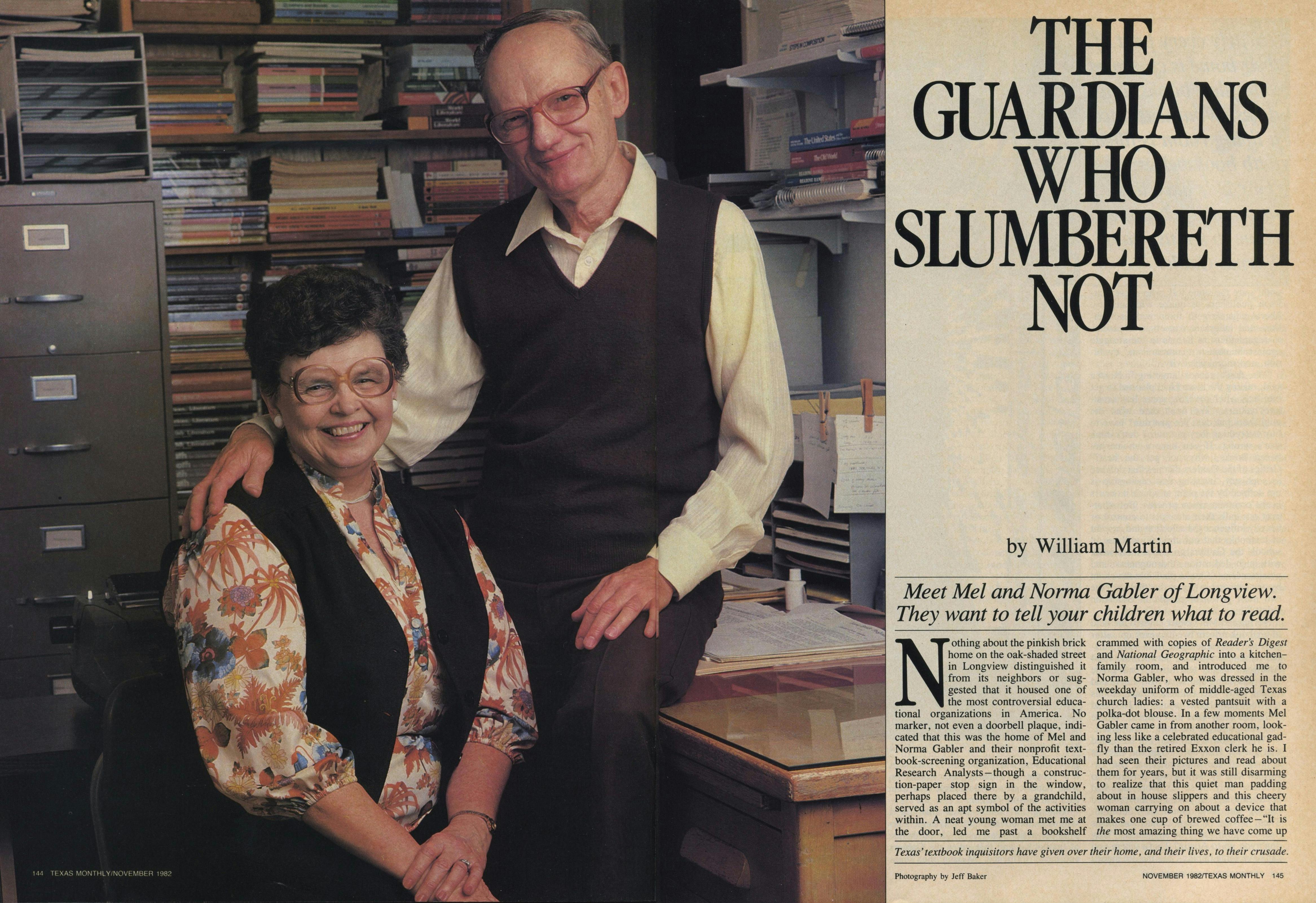

Nothing about the pinkish brick home on the oak-shaded street in Longview distinguished it from its neighbors or suggested that it housed one of the most controversial educational organizations in America. No marker, not even a doorbell plaque, indicated that this was the home of Mel and Norma Gabler and their nonprofit textbook-screening organization, Educational Research Analysts—though a construction-paper stop sign in the window, perhaps placed there by a grandchild, served as an apt symbol of the activities within. A neat young woman met me at the door, led me past a bookshelf crammed with copies of Reader’s Digest and National Geographic into a kitchen-family room, and introduced me to Norma Gabler, who was dressed in the weekday uniform of middle-aged Texas church ladies: a vested pantsuit with a polka-dot blouse. In a few moments Mel Gabler came in from another room, looking less like a celebrated educational gadfly than the retired Exxon clerk he is. I had seen their pictures and read about them for years, but it was still disarming to realize that this quiet man padding about in house slippers and this cheery woman carrying on about a device that makes one cup of brewed coffee—“It is the most amazing thing we have come up with”—are the same folk who cause textbook publishers to quake with anxiety, liberal educators to fume with indignation, and indignant conservative parents to regard them as heroes in the struggle against humanism, communism, evolution, and moral relativity.

“We don’t censor anything,” Norma said, raising the issue I had planned to get into only after covering some less sensitive matters. “We don’t care what the publishers put out. We just don’t have to buy everything they put out. I don’t think that’s wrong. If you have a choice between books, why not get the best?” Critics of the Gablers dismiss that defense as sophistry, insisting that censorship is not defined by the point at which it occurs in the communication process. But whatever one calls their attempts to control or heavily influence the selection and content of textbooks that our children will use in school, the Gablers go about their work with such dedication, thoroughness, and persistence as to make plausible the claim by one censorship expert that they are “the two most powerful people in education today.”

Norma and Mel Gabler entered the field of textbook reform twenty years ago, after their son Jim came home from school disturbed at discrepancies between the 1954 American history text his eleventh-grade class was using and what his parents had taught him. The Gablers compared his text to history books printed in 1885 and 1921 and discovered differences. “Where can you go to get the truth?” Jim asked.

“Well,” Norma told me, “I’m Irish, and that got my Irish up.” When the Gablers approached the superintendent, he explained that the school was permitted to purchase only those textbooks that had been screened and placed on an approved list by the State Board of Education. Then, in one of those casual comments that change history, he suggested, “Why don’t you go to Austin? That’s where you can have some impact.” Norma did indeed go to Austin, and for the past two decades few people have had greater impact on what American schoolchildren read than Mel and Norma Gabler.

Although 21 other states also use a statewide textbook adoption system, Texas is the nation’s largest single purchaser of textbooks, and that gives the Gablers enormous influence. Making the Texas list is practically a guarantee of profit for a publisher; failure to make it may doom a book, or a whole series of books, to extinction. Thus most publishers are understandably sensitive to pressures to make their books acceptable for use in this state’s 1100 public school districts.

Under the Texas system, the State Board of Education issues a textbook proclamation each spring, announcing the subjects and grade levels for which new books will be selected that year and inviting publishers to submit any books they wish to have considered. The board also appoints a fifteen-member committee, at least eight of whom must be classroom teachers in the pertinent subjects, to evaluate the books that are submitted. A list of these books can be obtained by anyone who requests it, and the books themselves are available at regional centers throughout the state. Citizens having objections to any books are invited to file written “bills of particulars” containing their specific complaints. Positive comments or general statements of disapproval are neither sought nor accepted. Near the end of the summer, the textbook committee meets to hear objections from citizens who have filed such bills and the publishers’ replies, then sends its recommendations, which may include as many as five books per subject, to the state commissioner of education. The commissioner considers the textbook committee’s list and may strike books from it (but not add to it) before submitting it to the board. Meanwhile, the Texas Education Agency scrutinizes the recommended books, the committee’s reviews, and the citizens’ objections and decides whether to request that publishers make changes in their texts. After a last round of hearings, the board makes its final decision. Then, following a similar set of procedures, local school boards decide which of the approved books they will select for use in their schools.

Norma Gabler went to hearing for the first time in 1962—and she went without Mel. “I had never traveled anywhere in my life by myself,” she explains, “but Mel said, ‘Honey, you’ve got to go, because I can’t.’ I said, ‘What will I do when I get there?’ and he said, ‘I don’t know, but you can do something.’ I was just going to do it that one year, but it was just something that went on and on.”

Mrs. Gabler recalls that in the early years she was sometimes treated badly by both publishers and textbook committee members. But she took her lumps, protested vociferously when the committee violated its own rules to give her opponents an advantage, and in 1970 won her first real victories. Beginning that year, publishers of science books containing material on evolution were required to include an introductory statement saying that evolution is a theory, not a fact. Publishers were also put on notice that no book would be adopted if it contained offensive language that would cause embarrassing situations in the classroom. Finally, the board agreed that all books up for adoption would be made available at twenty regional educational centers well in advance of the deadline for filing bills of particulars. “Those were the three biggest gains we ever had,” Norma says, “and it has been different from then on.”

During the seventies, the Gablers’ successes were more than procedural. Though they admit they can never be sure the textbook committee would not have reached the same decisions on its own, their objections clearly had an impact on the process. Today, publishers’ responses to their bills of particulars are often longer than the bills themselves.

As the Gablers gained credibility in Austin, they achieved hero status in the eyes of thousands of concerned parents, fundamentalist religious leaders, and conservatives of the sort now identified with the New Right. They began using hired assistants and volunteers to review textbooks and made copies of those reviews available to anyone who requested them. In 1973, after Mel took early retirement from Exxon Pipeline, thereby sacrificing some of the pension he would have received in seven more years, the Gablers formed Educational Research Analysts and have given full time to their mission ever since.

At last summer’s hearings Norma Gabler and the two young women who accompanied her dominated the first day of proceedings. For six hours, with a break in the morning and one for lunch, they repeated and elaborated on the objections contained in their bills of particulars, which filled six bound volumes and were available at a special table reserved for the press. An official with an overhead projector kept everyone informed of the elapsed time — a citizen is allowed ten minutes for each publisher whose books he opposes, though he can use his total allotment as he sees fit — but one sensed the Gabler women knew precisely where they stood every moment, as if they had carefully rehearsed and timed their performance. Members of the textbook committee, facing the Gabler team across an enormous conference table, occasionally showed wry amusement at some of their complaints, and textbook authors and publishers seated in a gallery of folding chairs at one end of the smoky room sometimes muttered in irritation or disbelief as they heard their books attacked, but it was clear they all took this East Texas grandmother quite seriously.

In addition to inundating the textbook committee, the Gablers produce a continuous stream of textbook-related materials and distribute them to conservative parents and groups in every state in the union and over two dozen foreign countries. They also maintain a hectic schedule of travel to meetings, consultations, and speaking engagements that takes them away from Longview more than two hundred days a year. They have been featured on 60 Minutes, Today, Nightline, Good Morning America, Donahue, Freeman Reports, The David Frost Show, syndicated religious broadcasts, and numerous local radio and television talk shows. A book describing their work, James Hefley’s Textbooks on Trial, went through four printings and is available in an updated paperback edition titled Are Textbooks Harming Your Children?

More important, they have become an integral institution of the New Right, whose agenda they share almost point for point. Their work is commended by Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell, anti-ERA activist and Eagle Forum founder Phyllis Schlafly, and New Right direct-mail expert Richard Viquerie. They participate in gatherings sponsored by such New Right organizations as the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress and the Texas-based Pro-Family Forum.

The Gablers receive no compensation for Educational Research Analysts; they live on Mel’s retirement and “a little Social Security.” They take an exceedingly modest honorarium ($300 plus expenses for the two of them) for their speaking engagements, and they put this money into the organization to cover salaries for assistants, printing and mailing costs, and travel to Austin. They charge a small fee for various publications but have to depend on contributions from supporters to cover much of their $120,000 annual budget. Critics sometimes speculate that they must be receiving secret payments from some conservative cabal, but a visit to their home makes it clear that they are what they profess to be: a totally dedicated couple who have surrendered their money, their time, and their space to a cause that they judge to be of overwhelming importance.

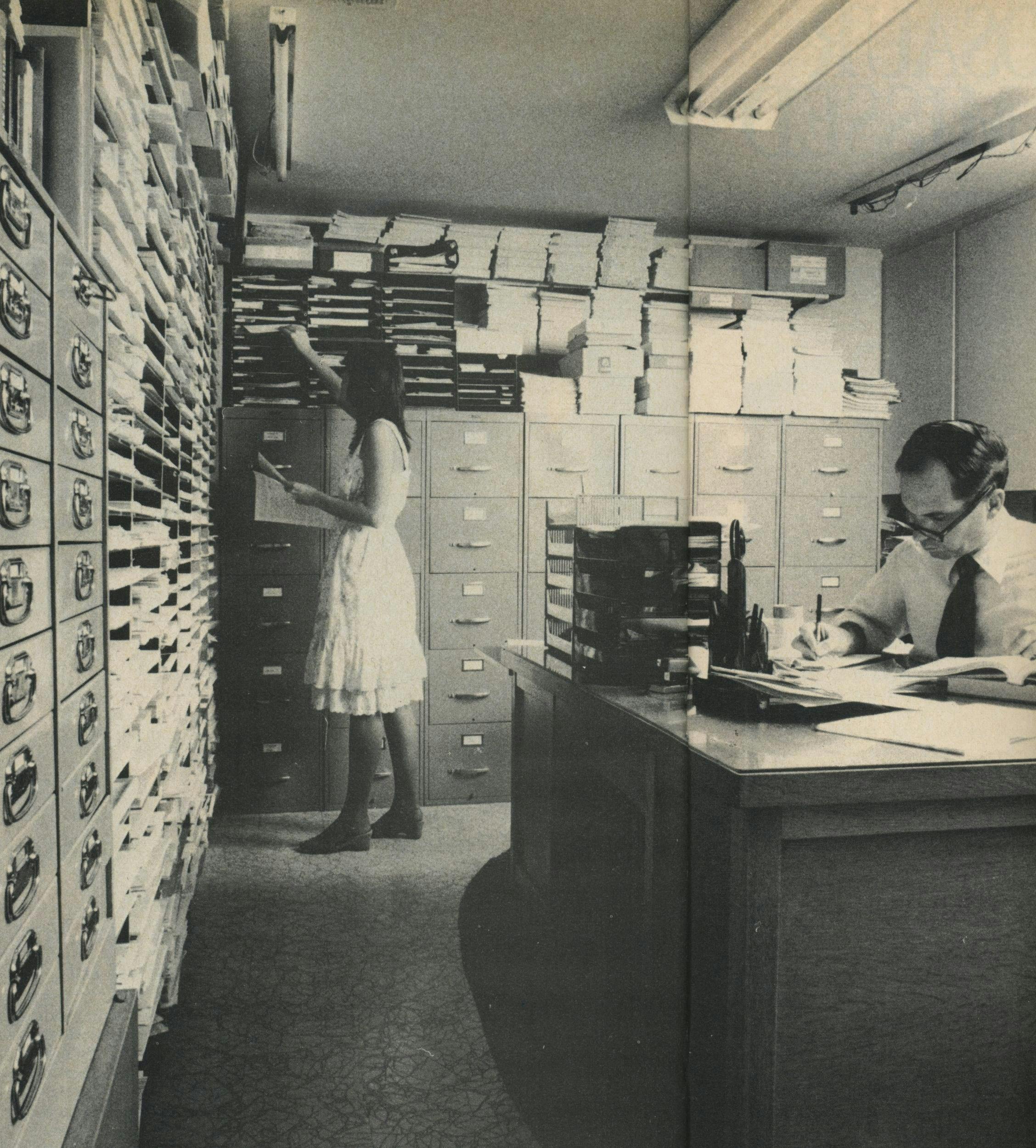

Nearly every part of their four-bedroom house is crammed with files, books, office equipment, and desks where young people pore over textbooks, answer letters, and assemble packets of material for parents’ groups and individuals who request their aid. What was once a living room is filled with bookshelves that jut out into the room, library style. A peninsula of files covers most of the floor space in another room. “There used to be a bed under here,” Norma said, “but we had to move it out. Our kids have to stay in a motel when they come to see us. We only have two hundred and twenty file cabinet drawers in our house.” Their own bedroom and the kitchen-family room are somewhat less densely packed, but the walls attest to their efforts with awards and plaques such as that from the Pro-Family Forum and the Eagle Forum of Southern Nevada, which declares them to be “Valiant Warriors of God who have devoted their lives to combat the evil forces that would destroy the virtue, nobility, and lofty potential of the youth of this nation.”

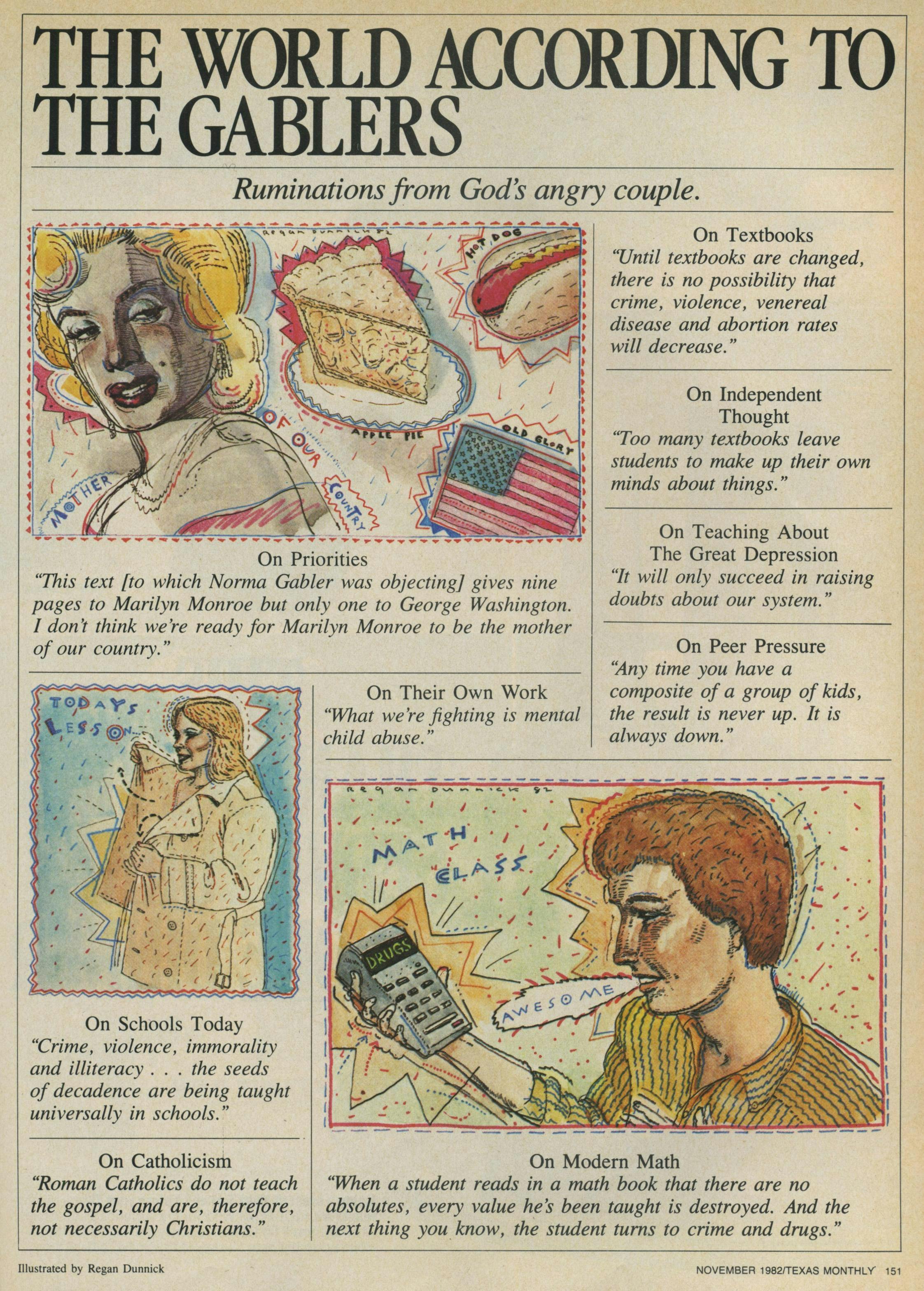

That textbooks should be regarded as dangerous weapons in an effort to destroy the minds and moral fiber of our nation’s children may strike some as surprising, but the Gablers certainly see them as such. “What we’re fighting,” Mel likes to say, “is mental child abuse.” Are Textbooks Harming Your Children? Quotes McGraw-Hill president Alexander J. Burke Jr., as observing that “textbooks both mirror and create our values” and cites publisher D.C. Heath’s dictum “Let me publish the textbooks of a nation and I care not who writes its song or makes its laws.” The Gablers evince no doubt that inferior, improper, and blatantly destructive textbooks are responsible for leaving young people unprepared to face the challenges of adulthood, for destroying confidence and pride in America, for undermining Judeo-Christian values, and for creating a society in which crime, violence, drugs, pornography, venereal disease, abortion, homosexuality, and broken families have become facts of everyday existence. “UNTIL TEXTBOOKS ARE CHANGED,” one of their information sheets declares, “there is no possibility that crime, violence, VD and abortion rates will decrease… TEXTBOOKS mold NATIONS because they largely determine HOW a nation votes, WHAT it becomes, and WHERE it goes! “

In their efforts “to rescue the hearts and minds of children” who are “ a captive audience” to what is presented to them in their textbooks, the Gablers and their helpers subject every book under consideration to a painstaking page-by-page, paragraph-by-paragraph, line-by-line, word-by-word examination, ferreting out what they regard as unsound or harmful material and preparing bills of particular and reviews that sometimes run to well over a hundred pages per subject. It is this uncompromising thoroughness that makes then such formidable opponents, since they often know the books far better than do the members of the textbook committee, and sometimes better than even the publishers who try to answer their objections.

The Gablers’ views are straight-forward and comprehensive. They believe that the purpose of education is “the imparting of factual knowledge, basic skills and cultural heritage” and that education is best accomplished in schools that emphasize a traditional curriculum of reading, math, and grammar, as well as patriotism, high moral standards, dress codes, and strict discipline, with respect and courtesy demanded from all students. They feel the kind of education they value has all but disappeared, and they lay the blame at the feet of that all-purpose New Right whipping boy, secular humanism, which they believe has infiltrated the school at every level but can be recognized most easily in textbooks.

Though they have gained most of their notoriety for protests that reflected ultra-conservative political and religious views, the Gablers have consistently — and rightly, in my view — stressed basic academic skills, with particular attention to the use of intensive phonics to teach reading. Their handbook on phonics is a helpful collection of articles and references that thoroughly documents the superiority of the phonetic over the “look-say” method of reading instruction, a method whose wide use in American schools seems to me not only to negate the chief advantage of an alphabet over pictographs but also to deserve much of the blame for the depressingly high rate of functional illiteracy in this country.

But the Gablers also feel that even those students who learn to read through intensive phonics, memorize their “times tables,” diagram sentences perfectly, and win spelling bees and math contests must still cope with an educational system that is geared to undermining their morals, their individuality, their pride in America, and their faith in God and the free enterprise system. Much of this corrosive work is accomplished through textbooks in history, social sciences, health, and homemaking.

The Gablers seem to believe not only that the proper subject of history is facts rather than concepts but also that all the essential pertinent facts are well known and should be taught as they were in older textbooks, in a clear chronological arrangement with a tone that is “fair, objective and patriotic.” They object to texts that omit reference to classic patriotic speeches such as Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” or that slight traditionally major figures in favor of lesser-known characters, particularly women and minorities. They think it is absurd for Crispus Attucks or Abigail Adams to get as much attention as Paul Revere or Benjamin Franklin and are deeply offended that George Washington Carver and Booker T. Washington have been de-emphasized in or dropped from some history books because they were perceived as having exemplified an Uncle Tom attitude that is no longer fashionable. “They dropped Carver along about 1960,” Mel observes, “because his philosophy was wrong. He thought every man ought to earn respect for himself. That’s not the philosophy of welfare.” Of a book that cited both Martin Luther and Martin Luther King, Jr., as reformers, the Gablers issued this criticism: “These two men should not be put in the same category. Martin Luther was a religiously dedicated, non-violent man.” In another particularly ethnocentric objection, they charged a textbook that described America as a nation of immigrant with presenting a derogatory view that did not foster patriotism.

As for contemporary events and issues, the Gablers object to texts that seem to manifest a bias — often documented by a meticulous counting of lines and pages given to a topic — not in keeping with familiar New Right positions on defense, capital punishment, gun control, civil rights, Taiwan, the Panama Canal, the labor movement, or women’s liberation. They dislike civic books that emphasize the flexibility rather than the stability of the U.S. Constitution, and they criticize any material that seems to encourage or condone change, dissatisfaction, rebellion, or protest, even though the major part of their lives is spent protesting and encouraging others to protest against the standing order in education and much of their own success stems from their having been able to get rules changed by bringing pressure to bear at critical points.

On matters of economics, the Gablers stand foursquare on the side of free enterprise and regard as inept any text that points out its shortcomings or that fails to take a hard line against socialism or communism. They are offended by books that depict the economic advances of the People’s Republic of China, and they quarrel with a text that lists America as third in per capita income, after Sweden and Switzerland, because it might lead children to believe that socialism, as practiced in Sweden, is something other than a radical system that always fails.

They are similarly protective of Christianity. When a world geography book suggests that primitive peoples may have developed religion and conceptions of gods in response to the uncertainties associated with harvests—a commonplace speculation among students of religion—they charge it with undermining traditional Judeo-Christian beliefs and ask, “How many parents are going to want their children to be taught that religion was developed merely to explain a natural phenomenon?” They object to books containing myths and legends that are reminiscent of Bible stories, though such stories abound in human culture, and to a suggestion that students check to see how many Asian religions have a concept like the golden rule at their core. Rather than regard such an assignment as an opportunity to amass evidence of the essential oneness of humanity—evidence that could easily be cited in defense of theism—they assert that “the significance of religions is their differences, not their similarities.”

The Gablers’ resistance to cultural variation and social change is seen nowhere more clearly than in their attitude toward sex roles. Predictably, their view of the family falls into the Father-Mother-Dick-Jane-Spot-and-Puff mold, with no doubt as to who does what. When texts note that the desire of women to earn pay equal to that of men, the Gablers complain that such equality could come only if women “abandon their highest profession—as mothers molding young lives.” They oppose any suggestion that divorce may have positive outcomes on the grounds that “divorce violates the religious opinions of many.” Books showing parents as flawed—not wicked, just imperfect and uncertain—are criticized for “emphasizing that parents, not teens, have problems.” And a text that observes that the environment in some homes may not be pleasant is criticized for weakening family relationships and justifying discontent.

Another prominent weapon in the humanists’ alleged attack on the family is sex education, which, the Gablers charge, offers young people an abundance of sexual information but no moral framework. As examples of books to which they have objected in past years, they showed me texts sporting pictures of vaginas and penises, describing homosexual acts, and repeatedly using the word “masturbation.” They also showed me, with some glee, a book that described the average penis as 38 millimeters in circumference. “An inch and a half around,” Norma chortled. “That’s less than a half-inch in diameter. That’s less than your little finger. I had Mel cut me a little dowel the size they said a penis was. That got quite a laugh down at Austin.” More seriously, they regard sex education as a parental right that should not be usurped by the school even if the parent is failing to provide it. “Silence,” they observe, “is a most underrated virtue. Talk in the classroom is no substitute for a quiet example at home.”

The Gablers feel that drug education is appropriate for schools, but they have presented a battery of objections to the way health textbooks deal with it. At the August hearings, they were consistently critical of books that gave more attention to alcohol, tobacco, coffee, and various over-the-counter drugs than to heroin, cocaine, or marijuana. Citing reports from Reader’s Digest and Ladies’ Home Journal, they attack books for saying that not all the dangers of marijuana are known, since many are known, and they ask for the removal of references to positive medicinal uses of marijuana, such as treating glaucoma and relieving nausea associated with chemotherapy, because “no such documentation has been offered.” On the contrary, they allege, “many scientists consider marijuana the world’s most dangerous drug.” Norma also criticized as unwise one text’s revelation that marijuana could be mixed into foods, noting, “This was tried here in Austin last month.”

In the scientific realm, the Gablers direct most of their fire at textbooks that espouse evolution, which they regard as a cornerstone of secular humanism (see box on page 148). They are, of course, well versed in the materials cited in support of a creationist, “young earth” viewpoint and claim they would not object to evolution’s being taught (as a theory, not a fact) if evidence for “sudden creation” were presented at the same time. It seems clear, however, that they would greatly prefer that textbooks give children no reason to think the universe might have been here for more than a few thousand years or that various forms of life have undergone significant evolutionary changes. They often introduce their criticisms of texts by describing them as being “blatantly evolutionary” or containing an excess of “evolutionary speculation” or “notable references to evolution,” and their publications speak approvingly of books in which most or all references to evolution have been eliminated. In response to a text that says, “As more knowledge is gained, and as new theories are tested against observed fact, ideas about the origin and structure of the universe and of our own world will no doubt continue to be changed and modified,” they complain, “This shows bias in favor of evolution.” Of another text that states, “No one knows exactly how people began raising plants for food instead of searching out wild plants,” they say, “The text states theory as fact, leaving no room for other theories, such as the Biblical account of Cain as a farmer.”

The Gablers’ attention to content is far-reaching and thoroughgoing, but they express almost equal dissatisfaction over the tone, values, emotions, and techniques they believe to be characteristic of modern education. They repeatedly object to what they call negative thinking. They have, I think, a valid point. There is a tendency in our culture to give more attention to bad news than to good and to offer handsome rewards to those who exploit our vulnerability to terror and our propensity to violence. Still, life even at the junior high level is not all Beaver and the Bobbseys, and I can’t help but think the Gablers are overreacting when, for example, they dismiss Poe’s classic tale “The Cask of Amontillado” as “gruesome, murderous, bizarre content. Not suitable for a literature class. The murderer shows no sign of regret!”

Closely related to the Gablers’ concern over negative content is their fear that public schools are undermining “absolute values.” Lest anyone misunderstand what they mean by this term, a pamphlet they distribute clears up most ambiguities. “To the vast majority of Americans,” it asserts, “the terms ‘values’ and ‘morals’ mean one thing, and one thing only; and that is the Christian-Judeo morals, values, and standards as given to us by God through His Word written in the Ten Commandments and the Bible….After all, according to history these ethics have prescribed the only code by which civilizations can effectively remain in existence!”

Any textbook that casts this viewpoint into the slightest doubt is targeted for opposition. Predictably, they object strenuously to books or teachers’ guides that describe in morally neural terms such primitive customs as exchanging wives or abandoning old people to die or that ask students if they can think of situations in which it might be permissible to tell a lie. Such texts, they claim, endorse situation ethics and subtly chip away at character and trustworthiness, making it difficult for children to stand firm in the traditional values they have learned at home. The best protection against this erosive process, they seem to believe, is to avoid any suggestion that people may legitimately differ on questions of value. Mel Gabler even feels that the new math contains the seeds of cultural disintegration. “When a student reads in a math book that there are no absolutes,” he has said, “every value he’s been taught is destroyed. And the next thing you know, the student turns to crime and drugs.”

One of the key defenses the Gablers use against what they regard as an attack on home-taught values is to charge texts and teachers with engaging in an invasion of privacy. Some of their fears are understandable, whether or not one happens to share them. I find it difficult, however, to understand what harm could come from asking children to take an inventory of the resources they use each day or to write about one way their lives have been influenced by their environment. Yet the Gablers view these exercises as unacceptable invasions of privacy. Indeed, in the name of privacy and protection of values, the Gablers object virtually anytime a text asks, “What do you think?” or “What is your opinion of…?” In testimony before the committee, a member of the Gabler team even objected to a home-making book because “it continually encourages students to be more introspective and not only to analyze themselves but also their parents, friends, and family.”

It is not a simple matter to discern just how successful the Gablers have been at influencing the decisions of the textbook committee. Norma readily acknowledges that “there is no way we can claim credit or success, because we don’t know what puts a book on or off a list. It could be the committee rejected a book for a different reason. They never tell us how judge. But what is encouraging to us is that back in 1973, six out of eight books we objected to in sociology and psychology were kicked out. In one year, seventeen out of twenty-seven were eliminated. In 1980, eleven out of twenty-one were eliminated. We hope some of that was because of what we did, but we can’t say for sure that it was.”

Some longtime observers and participants in the process feel the Gablers’ power is overrated. One such skeptic notes that in a recent year they objected to all twelve books in a given category. Since only five were selected, they could claim that seven out of twelve we eliminated without explaining that this would have been true had they not objected and that they had found fault with all of the books that eventually made the approved list as well. Allan O. Kownslar, a Trinity University historian, also doubts that the Gablers are as powerful as some believe. “I have written six textbooks for Texas,” he says. “They objected to almost all of them, and all of them were accepted.”

The publishers themselves walk something of a diplomatic tightrope. On the one hand, they voice concern over First Amendment rights, express a preference for leaving the preparation of textbooks to experts rather than to conservative ideologues who wish to force their views on all members of society, and manifest confidence that the textbook committee will make a wise decision. On the other hand, they acknowledge that the Gablers are a force to be reckoned with, prepare careful, detailed responses to the bills of particulars, and avoid direct confrontations with Norma and her assistants at the hearings.

Where the Gablers’ impact is more tangible, however, is in the content of the textbooks themselves. Without question, textbooks are changing along lines favored by the Gablers and the conservative parents’ groups that use their materials and tactics. The word “evolution,” for example, does not appear in a new biology text published by Laidlaw brothers, a division of Doubleday. “We deleted the term,” Laidlaw executive Eugene Frank explained, “because we wanted teachers to be permitted to teach biology without being forced to face controversy from pressure groups.” The volume in question is Doubleday’s only high school biology text. Another text, Land and People: A World Geography, put out by Scott, Foresman, was dropped from the Texas list because of its emphasis on evolution.

If we assume, as seems justified, that Mel and Norma Gabler do indeed wield sizable influence over American education, what are we to make of them and that circumstance? I found them to be courteous, pleasant, good-natured people who are earnestly, honestly, and unselfishly committed to helping the young obtain what they regard as the best possible education. I found myself applauding their concern, admiring their dedication, and agreeing with a number of their objections to specific texts. Yet I believe their crusade, if successful, will have a devastatingly negative effect on American education and culture.

To begin with, their attack on humanism as an evil spell that has been cast over Western Civilization-an attack in which they are joined by most of their New Right colleagues-is dangerously misleading. There are a few people who fit the New Right image of a humanist, who are indeed antireligious atheists and who blaspheme on the side. But for most people whom the New Right lumps into the secular humanist category, humanism is not a religion but an approach to the world. It is not, I think, an inherently reprehensible approach. It conceives of humans as having capacities of reason, mind, and will that far exceed those of other creatures and endow them with a singular dignity. It values diversity of opinion and rejects imposed or authoritarian approaches to knowledge, such as appeals to tradition or Scripture or other ostensibly revealed truth, in favor of free and critical inquiry, scientific methods, and individual and collective reflection. In maintains that to deserve our allegiance, beliefs about the world, society, and humanity should be based on — and not contradict — available evidence. It is skeptical of all claims to ultimate truth, because it has learned that not all the evidence is in.

In education, this humanistic approach does not seek to ply children with pot, pills, pornography, and polymorphous perversity. Rather, it strives to instill in them habits of mind and qualities of spirit that will include a love for knowledge, a depth and breadth of understanding, an ability to think well and critically for themselves, a belief in their essential worthiness and in that of others, and a desire and ability to work for the common good. It is not only part of the heritage of Western civilization, it is one of its best parts, and those who lump humanists into the same category as robbers, murderers, perverts, and “other treacherous individuals,” as prominent New Right leaders have done, are guilty as best of serious ignorance and at worst of slander and immorality of a contemptible sort in which Jews and Christians and other men and women of goodwill and integrity should have no part.

A major result of the Gablers’ misunderstanding of a humanistic approach to learning is a stunted and barren philosophy of education. In a manner typical of those distrustful of the intellectual enterprise, they take pleasure in scoring points against the professionals; Norma says she has read so many textbooks that “I figure I know enough to be a Ph.D.” It is clear, however, that they have little appreciation or understanding of the life of the mind as it is encouraged and practiced in many institutions of learning. They tend to cite the Reader’s Digest as if it were the New England Journal of Medicine and to regard a single conversation with a police chief or a former drug user as an incontrovertible refutation of some point they oppose.

In general, they know precisely where they stand but have difficulty dealing with a question that originates from different premises. Norma showed me a ninth-grade history book that observed that the route most likely taken by Israelites in their exodus from Egypt would have been across a swamp known as the Sea of Reeds. The book adds: “IT may be that the Sea of Reeds was later called the Red Sea by mistake.” Norma found this highly amusing: “Can you just imagine pharaoh’s army, with all his horses and all his men, completely disappearing into a swamp? Now, that’s a miracle!” I pointed out to her that many scholars feel the biblical story may be an embellished, rather than strictly accurate, account of Israel’s escape from slavery. I noted that there is no record in Egyptian history of such a catastrophic event, and that the Hebrew Bible does indeed say “Reed Sea,” not “Red Sea.” She faltered, then said: “But still…okay…what happened to pharaoh’s army?”

In similar fashion, questions posed by members of the textbook committee at the August hearings characteristically received oblique answers or a puzzled “I don’t think I understand the question.” That, of course, is the point: when one regards education as simply the ingestion of facts and not the investigation and analysis of ironies, ambiguities, uncertainties, and contradictions, one will be far less likely either to understand the question or to provide a useful answer. And that kind of trained incapacity will endanger the vitality and ultimately the survival of treasured forms of religious, political, social, and economic life.

Norma Gabler’s difficulty with unanticipated questions is a communicable disease, and she is working to spread it. “What some textbooks are doing,” she has complained, “is giving students ideas, and ideas will never do them as much good as facts.” Further, in her view students should apparently not show any interest in facts not found in their textbooks. Norma objected to a fourth-grade book that urged students to verify facts by consulting other sources, on the grounds that “it could lead to some very dangerous information.” When committee members pressed her to elaborate, she said, “I just don’t think questions should be asked unless the information has already been covered in the text.”

The shortcomings of the Gablers’ view of education — as a process by which young people are indoctrinated with facts certified to be danger-free, while being protected from exposure to information that might challenge orthodox interpretations — can be seen by looking at three areas: history, science, and the social sciences. One may or may not agree with the particular objections the Gablers make to various history books, but it is clear that they are oblivious to the idea that the writing of history has never been, nor can it ever be, factual in any pure sense. Those who provided eyewitness accounts and other records with which historians work were engaged in interpretation, not only in adjusting the light under which they chose to display the materials they assembled but even in their selection of events, dates, and people from the infinite possibilities open to them. And to imagine that they or anyone else engaging in the historical enterprise does so free of the influence of his or her values, perceptions, and ideological biases is to believe something no reputable historian has believed for generations.

The Gablers seem incapable of considering the possibility that a textbook might meet their criteria of fairness, objectivity, and patriotism and still be critical of any aspect of American life. To bend a metaphor, it is as if they hoped that by refusing to acknowledge the existence of new materials, techniques, social conditions, and fashions, they might somehow persuade the emperor to keep wearing his comfortable, if somewhat threadbare, old clothes. To be sure, new versions of history may be inferior to earlier ones. But with free inquiry, each new construction can be examined for accuracy, adequacy, method, logic, and insight. When orthodoxy is the only criterion, there can be no search for the broader, deeper, more lasting truths that make men and women and children free.

Efforts by the Gablers and other fundamentalist Christians to negate the teaching of evolution are probably even more detrimental to the educational process and the long-term welfare of the country. Fundamentalists typically belittle evolution as “just a theory, not a fact,” as if theories are mere speculations or guesses dreamed up by scientists in idle moments. As scientists use the term, however, a theory is a description of natural phenomena, based on long observation and, if possible, experimentation. To obtain the status of theory — as in cell theory, quantum theory, and the theories of gravitation and relativity — these descriptions must be supported by an abundance of evidence that has been critically examined, argued over, and organized into what is regarded as the best explanation for the phenomena in question, or one of a very small number of competitors. Evolution is such a theory. Creationism is not.

Millions of fundamentalist Christians believe in sudden creation and a young earth because that appears to be required by a literal reading of Genesis. Other millions of Christians regard the Genesis account of creation not as a scientific description of the origins of the earth and humankind but as a religious story — a myth, if you insist — whose purpose is to affirm the belief that behind the universe is God. Other cultures have comparable stories. The one is ours. It is a fine story, perhaps “true” in some ultimate sense, but it should not be asked to bear the weight of a scientific theory, because it cannot. Creationists can mount a case that sounds impressive to a layperson and can sometimes score points against scientists unaccustomed to defending their views in public debates or on radio and television talk shows. But when they tackle true scientists who are onto their game, as in the 1981 Arkansas creationist trial, they lose, and they lose because creationism is neither demonstrable fact or theory but a religious belief that runs counter to available evidence. The case for creationism is not made by people who have had any noticeable impact as scientists. As the Arkansas trial revealed, no reputable scientific journal has published an article espousing scientific creationism. Moreover, several leading spokesmen of creationism claim doctoral degrees from institutions that, if they exist at all, are unaccredited.

Just because the tenets of creationism are scientifically insupportable, however, does not mean creationists will lose – witness the changes, already noted, in biology books used in this state. If the earth is indeed several billion years old and if evolution is the best explanation for life on this planet, as experts in anthropology, archeology, astronomy, biology, biochemistry, ethnology, geology, and physics insist is the case, then to deny young people access to the best available theory is to leave them incapable of continuing the astonishing scientific advances that have been a hallmark of this nation.

The Gablers’ attack on moral and cultural relativism is aimed primarily at the social sciences. Without question, the loss of certainty engendered by opening windows on a wider world can be distressing. It is probably true, as many social commentators have observed, that civilizations work better when there is consensus on basic values, and that some of our most pressing social problems — crime, for example — are closely related to a break-down of such consensus. We have, since at least the sixties, experienced a crisis of values that has led to a crisis of legitimation in which we have withdrawn from basic institutions — family, schools, business, government, religion — the confidence and trust we once granted them, replacing those attitudes with skepticism, cynicism, and hostility. This is not a benign development, and the upsurge of evangelical religion, the Moral Majority, the Coalition for Better Television, Educational Research Analysts, and other manifestations of conservative ideology is a reaction to it.

One of the great challenges facing our society — and there is no guarantee that we will meet it successfully — is to reestablish a balance between adherence to a set of basic values and acceptance of individual and cultural variation. I appreciate the Gablers’ desire to participate in that effort. I do not, however, think we will be well served by believing that either Longview or Houston is the center of the universe, that all flags should be red, white, and blue, or that “Jesus Saves” should be adopted as the international anthem. We live in a multicultural world — something children learn very early, mainly from television but also from newspapers, from movies, and, particularly in large cities, from their neighbors and schoolmates. If we cannot learn to accept that fact and its profound implication, which social scientists are committed to explore and explain, we may not be able to keep our world.

A final quarrel I have with the Gablers is their contribution to a growing climate of censorship. In the two years since the New Right’s impressive show of muscle in November 1980, complaints to the American Library Association about attempts to remove or restrict access to material in classrooms and libraries have risen by more than 300 per cent. As one consequence, some teachers admit that they avoid introducing anything controversial into their classes, or they tape class discussions that might conceivably be misconstrued, or they teach material that is no longer relevant or in which they do not believe, simply to keep from losing their jobs or being hassled by unhappy parents.

As noted earlier, the Gablers claim they are not censors because they do not try to say what can be published. They also object to being judged by a double standard. “When we try to get changes made,” Norma said, “it’s called censorship. When minorities and feminists do the same thing, nobody complains.” But whether regarding them as censors or as honest competitors in the marketplace of ideas, their critics have become increasingly vocal.

One group of critics is People for the American Way, founded in 1980 by TV producer Norman Lear and led in Texas by Michael Hudson, a graduate of West Point and the University of Texas law school. Though he did not open an Austin office until mid-July, Hudson managed a quick and impressive victory when the State Board of Education let him respond in writing to Gablers’ bills of particulars. He still feels, however, that citizens should be permitted not only to register objections but also to speak in favor of textbooks they find especially meritorious. A number of educators and publishers agree, although most regard the Texas system, with its openness, as the finest in the country. Aside from some procedural fine-tuning, it would appear that what is need is not less input from the Gablers but more from those with a different view and experience of education.

I have three children. Two are now grown men; my daughter entered the eleventh grade this fall. My wife and I have attempted for over two decades to expose them to a kind of education and cultural experience that is radically different from that endorsed by the Gablers. And yet they have mastered basic skills, they have good values, they work hard, they know a great deal, they think exceptionally well, and they have made solid contributions to the varied groups in which they participated. They are not perfect, but they please me enormously. What is more, I have taught thousands of young people who have experienced a similar kind of education and who seem to me to be, well, almost as promising as my own offspring.

It may not be possible to prove that an open mind is better than a closed one, or that the proper antidote to a bad idea is not censorship but a good idea, or that a society in which some questions are never answered may be preferable to one in which some answers are never questioned, but I believe these things to be true. I not only believe them; I have bet my life on them.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Higher Education