This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The day after Attorney General John Hill lost his campaign to become governor of Texas, a pair of Dallas attorneys rushed to Austin to see him. The two men were Thomas Luce III and Vester Hughes, Jr., the founder and the legal superstar, respectively, of a five-year-old Dallas law firm called Hughes, Luce, Hennessy, Smith, and Castle. They were a new kind of lawyer; eager and ambitious, they had little use for staid legal traditions. On that particular day the two attorneys were in a hurry to see Hill because they knew his unexpected defeat by Bill Clements could mean good news for them. Hill naturally would have expected to spend the next four years in the governor’s mansion. Now he was suddenly available. Luce and Hughes wanted Hill to join their firm, but they knew the attorney general was certain to receive myriad offers from corporate law firms around Texas. They wanted to get to him first.

Hill was precisely the type of figure who could bring instant respectability to a firm on the make. He was not only a prominent man with valuable connections but also one of the state’s top trial lawyers. Ushered into Hill’s office, the Dallas lawyers made their pitch. Hill was doubtful; he wanted to stay in Austin, where the young Dallas firm had no office, he explained. “We’ll open one,” Luce responded swiftly. Hill pointed out that he was a plaintiffs’ lawyer, specializing in personal injury and wrongful death cases while most large private firms represented only defendants in such cases. No problem, the Dallas lawyers replied; they would be happy to let Hill do plaintiff work. After several weeks of negotiations Hill was won over. He got his Austin office as well as spacious quarters and a secretary in the firm’s Dallas office, where he would spend two or three days a week. The partners of the Dallas firm were ecstatic. When Hill arrived, they paid the firm’s newest partner the highest honor of all: excising four names from their letterhead, they rechristened the firm Hughes and Hill.

After two weeks on the job the man the firm had courted with such ardor padded down Hughes and Hill’s hushed, carpeted hallway in a downtown Dallas bank building. He stopped at the office of the firm’s general manager and asked if he might have his first paycheck. The administrator checked his records. It seemed that Hill had not filled out his time sheet, noting the hours he had worked for the firm’s clients. At Hughes and Hill lawyers weren’t paid until all billable hours had been accounted for. The honeymoon was over. John Hill had just joined the brave new world of life in the law firm fast lane.

In the old days Texas’ corporate lawyers had things their way. They were powerful string-pullers behind the scenes, the crucial links between banks and businesses. Their corporate clients came to them and stayed with them for generations, willingly paying massive bills—rarely detailed—without complaint. Under the cloak of gentlemanliness new business was quietly solicited at the country club or on the golf course. And once attorneys joined big law firms their futures were assured. They paid their dues and then lived off the enormous profits generated by new recruits.

But then came a rude awakening. Banks were deregulated. Corporations began merging and divesting, taking over one another. The cozy alliances that had fueled the big-firm machinery were shattered. Giant companies became fed up with their legal bills and started to shop for cheaper rates and to cut costs further by establishing in-house legal staffs.

Very quickly a new kind of law practice developed. It is far more competitive, far less genteel. Law firms now hire headhunters to steal lawyers from one another, and they employ PR firms to design slick sales brochures to attract clients. They drop big money to woo recruits. They plot to enter new markets, invest in real estate, even conduct mergers and acquisitions with other law firms. Among big-firm attorneys the most popular reading is In Search of Excellence. “Aggressive” has replaced “distinguished” as the premier adjective to bestow upon an attorney.

Some of that modernization is good. Firms have opened their ranks to women and minorities and have become more democratic. They have been forced to redistribute wealth and influence on the basis of merit rather than seniority. But much about the new age costs the public. The traditional lawyer’s role was that of attorney and counselor—not merely courtroom warrior but also adviser. Because lawyers used to work for a flat fee, their incentive was to resolve disputes without going to court. They advised their clients when a claim was frivolous.

Today’s big-firm lawyers are hired guns, employed by the job and paid by the hour. They are measured not by their success in achieving a result that serves both client and society but by the number of billable hours they produce. The result is an incentive to produce as much billable time as possible—and that means litigation. Texas now has 44,500 lawyers—twice as many as just twelve years ago—filing more than 350,000 lawsuits a year in state courts. So swollen is the backlog of pending cases that even if the filing of new lawsuits were completely halted, it would take eighteen months to catch up. It is an unsettling fact that lawyers today are in the business of obstructing progress. That affects everyone. The soaring cost of malpractice litigation makes medical care more expensive. The expense of defending personal injury suits hikes the price of automobile insurance. Corporate takeover battles, in which lawyers play knights to boardroom King Arthurs, result in the waste of millions on Wall Street gamesmanship that instead could produce new products and more jobs.

Meanwhile, attorneys’ fees and salaries are up; rates run to $4 a minute. Beginning lawyers at big firms earn up to $47,000 a year, twice the going rate of ten years ago. New partners, men and women in their early thirties, make $100,000, and senior partners at the most profitable firms earn six times that. The old notion that practicing law was a privilege with an accompanying set of responsibilities is fading swiftly. Pro bono work, or legal services performed free as a community service, is little more than a pleasant memory. “I don’t think lawyers are worth what they’re paid,” says managing partner Louis Paine of the Houston firm Butler and Binion. “Money is the root of all evil in the legal profession.” Every day the modern attorney increases his influence over our lives. Big-firm lawyers arranged the settlement that has turned the state’s prison system upside down. They helped decide which schoolchildren would be bused. A lawyer in the Austin office of a Houston firm played a key role in attracting the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (MCC) to Texas. A Dallas attorney presides over the Dallas Chamber of Commerce. Most of us will never enter the swanky reception areas of Texas’ major law firms. But the values and actions of the new breed of attorneys will affect us all. In one way or another we are all their clients. And one way or another we all end up footing the bill.

The New Go-getters

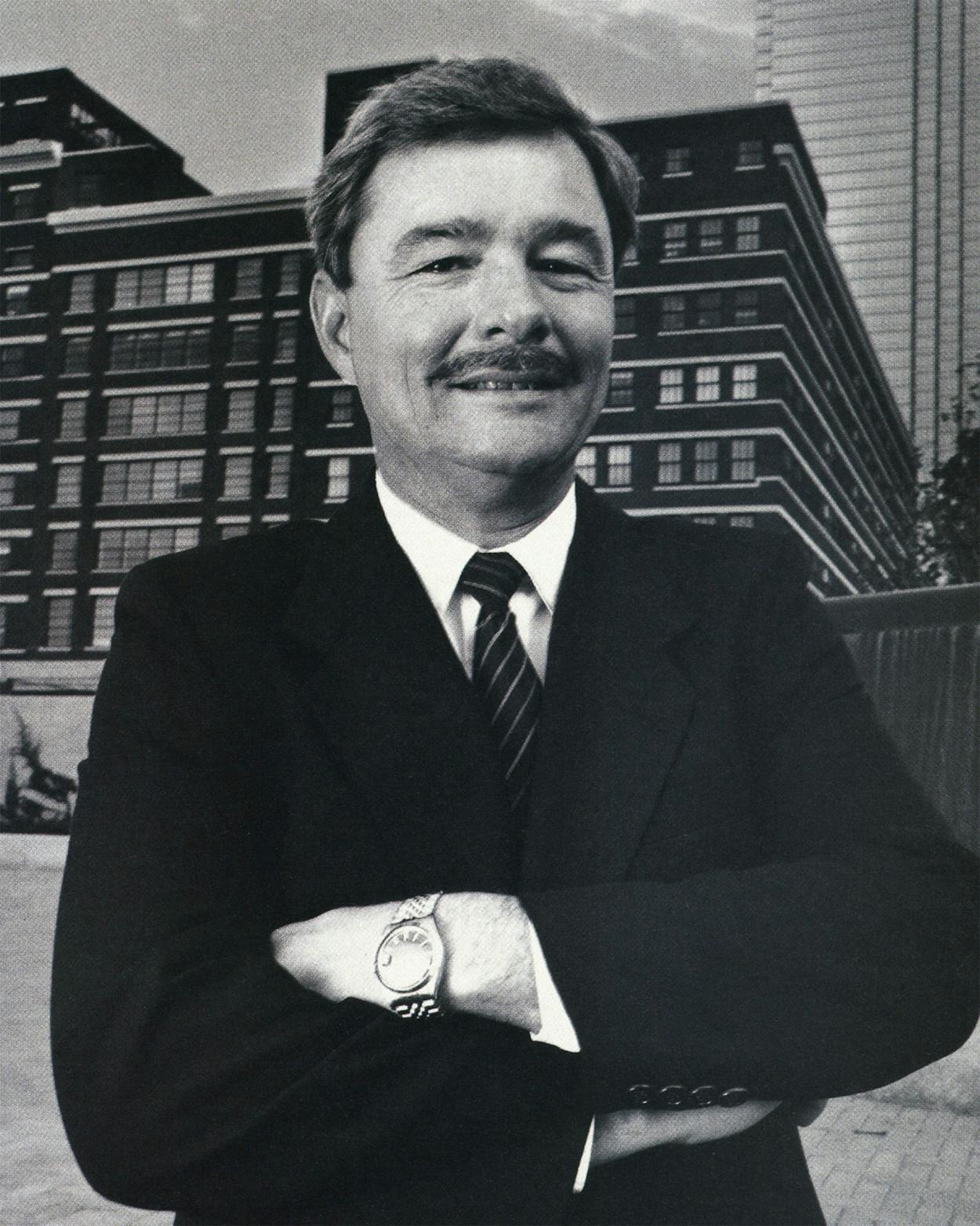

John R. Johnson, the mustachioed managing partner of a Dallas firm called Johnson and Swanson, works in a large corner office at Founders Square, an elegantly renovated building half owned by his firm. Oriental rugs cover the parquet floors. The head of a giant Wyoming elk adorns one fabric-covered wall; a Cape buffalo trophy dominates another. They are souvenirs of Johnson’s hunting expeditions with close friends like Bill Clements and Ray Hunt, two of the firm’s valued clients. They also symbolize a new predatory work ethic. “There’s a mythology that lawyers are professionals, they aren’t business people,” says Johnson. “Law firms are major employers in this city. It’s clearly a business. You can’t be a successful law firm today without acting like a business.”

Such is the gospel of today’s big law firm, of which Johnson and Swanson is a prime example. Founded in 1970 by five young lawyers, Johnson and Swanson today employs 160 attorneys, more than any other Dallas firm. The rise of megafirms in Dallas has recast the state’s legal landscape. A decade ago Houston’s Big Three—Vinson and Elkins, Fulbright and Jaworski, Baker and Botts—were the only Texas firms with more than a hundred lawyers; they ranked among the ten largest in the country. Of sixteen firms today with more than a hundred Texas attorneys, ten are in Dallas, six in Houston. Dallas, the city of genteel businessmen, has become the state capital of cutthroat legal practice. The large Houston firms have continued to grow, but they have slipped several notches in the national rankings. Some find themselves playing a game of catch-up, struggling to adapt to the new era.

How can you tell a modern firm from a legal dinosaur? It’s easy, once you know the rules.

• Money talks. For years most law firms kept their finances secret from everyone—including the majority of their own attorneys. Not a new-age firm—or Houston’s Vinson and Elkins, which has long thrived on the credo that money matters. The largest firm in Texas, Vinson and Elkins employs 1240 people, including 400 lawyers, and has branch offices in Austin, Washington, and London. In an age when billing clients is the name of the game Vinson and Elkins compiles its own scorecard. Each month the firm circulates a list of each attorney’s client billings, with figures for the year to date and the previous year for those interested in easy comparisons. It is known as the Hero Sheet. To the greatest heroes go the greatest rewards—the firm bases partner salaries heavily on individual billings. Those wondering what their peers make merely have to look; a list of every check issued by Vinson and Elkins is circulated throughout the firm. Crass? Yes. But it works. Though Vinson and Elkins ranks eleventh in the country in number of lawyers, its gross revenues of $106.5 million placed it fourth in the country this year.

Even the most traditional firms have followed suit. At Houston’s Baker and Botts, the third-largest Texas firm with 283 lawyers, new managing partner E. William Barnett last year began sharing closely guarded financial information with associates. At the firm production is now a major consideration in setting salaries. (Attorneys who progressed from associates to junior partners to senior partners once moved forward in lockstep.) Less-productive senior attorneys’ salaries were cut by as much as $50,000 a year.

• Make lawyers comfy. If you want lawyers to bill day and night, you have to make them feel important. Vinson and Elkins’ main office sprawls throughout twelve lushly furnished floors of the First City Tower. Soothing designer tones predominate. The quarters contain a 100,000-volume law library, a coffee station on each floor, and 28 conference rooms. Dial a number, and the firm will send flowers and fruit to your clients. Dial another, and your flight reservations are made. Need a briefcase? No problem. The firm keeps its own stock on hand.

• Tradition isn’t everything. For many years Baker and Botts was Houston’s Ivy League firm. Then it began having trouble recruiting attorneys. In 1980 only 11 new associates joined the firm. Always third of the Big Three in size, Baker and Botts fell farther behind Vinson and Elkins and Fulbright. What to do? Shop around. Baker and Botts now visits nearly fifty schools in search of recruits—twice as many as before. “A young guy in our Dallas office was first in his class at Kansas,” managing partner Barnett said, somewhat astonished. “We never had anybody from Kansas.”

• Invade your neighbor’s turf. To drum up more business, Houston firms are opening Dallas offices, and Dallas firms have moved into Houston. Baker and Botts, for instance, has just established a beachhead in Dallas. “Dallas is so logical,” notes one of the firm’s partners, “it plays to our strengths.” Countered Christie Flanagan, managing partner of Dallas’ Jenkens and Gilchrist, “Those Houston lawyers will learn memberships in the River Oaks Country Club aren’t transferable.”

• Hustle at all times. Johnson and Swanson created its own big break. One Friday in 1972 W. Tack Thomas, a loan officer for First National Bank, agreed to let partner Linton Barbee handle a loan deal, provided the loan went through. Thomas told Barbee they should meet again the following Monday to decide what legal documents the transaction would require. Barbee showed up for his appointment with the legal papers completed, awaiting Thomas’ signature. Thomas went on to become president of what would later become InterFirst, and Johnson and Swanson went on to become the bank holding company’s lead law firm.

• Money’s more important than prestige. An internal committee studying Fulbright and Jaworski’s move from its run-down quarters at the Bank of the Southwest last year presented the partnership with two options. First was the Allied Bank Plaza, a 71-story green-glass skyscraper in the center of downtown Houston, just a short walk from the federal courthouse. The alternative was the Gulf Tower, a 52-story gray granite structure perched on the eastern edge of downtown, set away from most of the banks and the oil companies. The issue split the firm into two camps. On one side stood most of Fulbright’s corporate and labor lawyers, who argued that the firm needed the status of a mainstream location. Opposed was the larger group of trial lawyers, particularly the younger ones, who favored the cheaper Gulf space. They knew the Allied rent would come out of their pockets. After a bitter debate the firm chose the Gulf Tower. Economy won out.

• Diversify. Like department stores, law firms have to protect themselves against shifting trends in the marketplace. Bracewell and Patterson, once the hottest of Houston’s Big Six law firms, lost a bet that energy work would carry it to greatness. Fulbright built its reputation on its large, well-trained insurance defense trial section. Unfortunately, insurance work is far less lucrative than other types of practice today. Although 1984 was Fulbright’s most profitable year, an American Lawyer survey showed that the firm earns far less per lawyer than the other two Houston megafirms.

• Connections count. In the old days lawyers were content to remain behind-the-scenes power brokers. Not anymore. Vinson and Elkins has made a religion out of being political, hiring superstars whose primary job is to attract attention and business. John Connally filled the slot for years. He has been replaced by another presidential candidate, former U.S. Senate majority leader Howard Baker, who toils in the firm’s Washington office for the tidy sum of $750,000. He’s not being paid to write impassioned legal briefs. He’s there because he knows everybody, and he is expected to bring his friends to Vinson and Elkins. The firm helps grease the wheels by doling out nearly $300,000 to political campaigns—more than any law firm political action committee in the country. And the list of recipients shows that pragmatism, not ideology, governs the distribution of money. The recipients include politicians of every stripe, most of them incumbents.

John Johnson of Johnson and Swanson has cracked the most lucrative network of all. Three years ago he became one of the few lawyers granted admission to the Dallas Citizens Council, the mythic businessmen’s group that for years controlled the city. This year Johnson became the first attorney to run the Dallas Chamber of Commerce.

• Always remember, law is a business. “You need the corporate culture, the corporate mentality,” says Jenkens and Gilchrist’s Christie Flanagan. “I describe our structure in corporate terms. You have the partners, whom I view as shareholders. Your board of directors [management committee] is elected by your partners. One of them is managing partner. He’s your CEO.”

Buying the Best

Imagine how major college football coaches would recruit if there was no longer even the pretense of NCAA rules, and you will have an idea how large law firms pursue the best law students. It begins during January of the first year, only five months after school starts. Spurred by a single set of midterm grades, determined by a single exam, the firms launch their version of rush. They are looking to fill their summer internship programs, for which they hire top students with hopes of luring them back after graduation. Until the early seventies big Houston firms pretty much had UT’s best students to themselves, and the sleepy Dallas firms picked up the few young lawyers they needed at SMU. Now both cities are filled with large, booming law firms that must hire dozens of new associates to maintain their growth. The Texas firms must also compete with bluechip firms from out of state.

All large firms today have full-time recruiting staffs charged with coordinating the process and keeping clerks happy when they arrive. Vinson and Elkins hired a former stewardess and personnel manager for Pan Am. In pursuit of 53 new lawyers the giant Houston firm visited thirty law schools in twenty states this year. UT has an entering class of five hundred students; four hundred firms will visit the school to recruit them. Despite the increased demand, big firms are interested only in the top 20 or 30 per cent of the class. Those students are the battleground.

Competition has spiraled new associate salaries at the top-paying firms in Dallas to as much as $47,000. Houston’s megafirms, which offered a mere $40,000 to graduates of the class of 1985, pledge to match whatever Dallas pays next year. Blue-chip small firms dole out even more; Miller, Keeton, Bristow, and Brown, a thirteen-lawyer Houston trial firm started by superstar refugees from the Big Three, offers rookies $55,000.

Not surprisingly, young lawyers have come to consider fat salaries their due. In 1982, when new lawyers were making $35,000, Butler and Binion’s summer associates showed up at a beach party with T-shirts reading “$45K Not a Penny Less.” Even those perpetuating the orgy acknowledge that it has gone too far. “The salaries are ridiculous,” says Alan Feld, managing partner for the Dallas office of Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer, and Feld. “They aren’t worth it. It’s simply a function of the worst-managed firm raising salaries and everybody following in sheeplike fashion.” Explanations for why it continues sound like discussions about what perpetuates the nuclear arms race. Admits Feld, “It’s pretty stupid, but everybody does it.”

To understand the lengths to which firms will go to capture a coveted prospect, consider the courtship of Rebecca Hurley. In the summer of 1981 Richard Freling, a prominent tax attorney with the Dallas firm of Jenkens and Gilchrist, spent lunch listening to SMU law professor Alan Bromberg rave about a student. When Freling returned to his office he wrote a note to a partner in charge of recruiting. It contained a single question: “Who is Becky Hurley, and why aren’t we recruiting her?”

Rebecca Hurley, Freling soon learned, had it all. She had been first in her class at SMU law school for two years running and had been leading articles editor of the law review. A native of Shreveport, Louisiana, Hurley was just the kind of go-getter Jenkens wanted: a lean, tall, tightly coiled woman, articulate and charming, brimming with energy.

Freling knew that the odds against Jenkens’ hiring Hurley were great. She had split her first two summers during law school working at four other firms, and students usually went where they had clerked. Moreover, everyone in town wanted Becky Hurley. In her two years she had applied for 24 summer positions and had been courted for every one. Still, Freling thought there might be a chance.

Hurley was a veteran of this strange ritual. Firms had begun inviting her to lunch in her first year in law school, when the first round of grades placed her at the top of the class. She had spent half her first summer at Dallas’ Carrington, Coleman, Sloman, and Blumenthal and half at Johnson and Swanson. During that time she learned the meaning of hard sell as partners vied for her favors. “I never bought a lunch, not a day,” she recalls. “I’d get calls one after another. ‘Can you have lunch today? How about a week from now?’ It was exhausting.”

While Hurley was finishing up her first summer as a clerk, another large Dallas firm, Winstead, McGuire, Sechrest, and Minick, took Hurley and one of her law school classmates to lunch. The firm’s recruiter promptly announced that he was offering jobs on the spot for the following summer—not only to the two of them but also to their three best friends. It was a classic recruiting maneuver: offer scholarships to the star quarterback’s best friends in hopes of bagging the quarterback.

Typing Hurley as a feminist, yet another Dallas firm, Jackson, Walker, Winstead, Cantwell, and Miller, dispatched four female lawyers to take her to dinner at Neiman-Marcus Fortnight. The technique worked; Hurley agreed to split her second summer between that firm and another, Thompson and Knight. When she called Dallas’ Locke, Purnell, Boren, Laney, and Neely to say that she had accepted another offer, the firm’s recruiter announced that he was crushed. “I really thought you’d fit in well,” he moaned. “It’s just awful.” Becky Hurley had become a heartbreaker.

It was during that summer after her second year of law school that Richard Freling began calling. A friend at the firm encouraged Hurley to listen. “The people who go to Jenkens are real movers and shakers—just like you,” she said. Freling took Hurley to the City Club for drinks and to fancy restaurants for lunch. But Hurley held him off; she told him she was going to spend the next year working for a federal judge and would not decide what job to accept until after she had graduated. Undeterred, he kept calling.

Late in the fall of 1982 Hurley told Jenkens she would accept a permanent offer. Freling was jubilant. The long mating dance seemed to be over at last. The firm took her out for a congratulatory evening: dinner at Jean Claude’s, drinks at the Mansion. “Now that you’re on board, do you have any questions?” Freling asked. “Now that I’m on board, Richard,” asked Hurley, “will I ever see you again?”

In December Becky Hurley learned that she had been accepted for a prestigious clerkship with the U.S. Supreme Court; she would spend a year working for Chief Justice Warren Burger. That meant, of course, that all bets were off. She would have to sever her ties with Jenkens until the clerkship was over. And—woe to Jenkens—she would have time to reconsider her choice while in Washington.

Jenkens was taking no chances. Before Hurley left for Washington the firm held a luncheon in her honor at the Tower Club. The federal judge for whom she had clerked was there, as were her fiancé and two dozen members of the firm’s tax section. Christie Flanagan, the firm’s managing partner, gave a speech. Hurley was so touched that tears came to her eyes. “You’ve all made me feel so much a part of the firm,” she told the group, “and I haven’t even worked here one day.”

On hearing about Hurley’s clerkship, Freling had sent her a dozen long-stemmed roses. But by then she had heard astonishing news. After twenty years at Jenkens, Freling had left for the rival firm of Johnson and Swanson. Freling called Hurley a few days later. “I don’t want you to misunderstand my decision to leave,” he said. “I’d like to talk to you about Johnson and Swanson.” Hurley was dumbfounded. Freling had spent months selling Jenkens. He had talked to her just weeks earlier about why it was the best firm in town. Now he was asking her to go somewhere else. Hurley told Freling not to call her again.

When she arrived in Washington, East Coast firms joined in the Hurley hunt. One had a cocktail party for her. Another took Hurley and her new husband to New York for a weekend spree: rooms at the Ritz, a limousine, a Broadway show, dessert at the Plaza. But Hurley was homesick for Dallas. What to do? She called an attorney at Jenkens. He gave her his American Express card number. Come to Dallas for a weekend, he told her. “We’ll fly you down and put you up at the Adolphus. Come into the office for half a day, and spend the rest of the time doing what you want.” Hurley and her husband flew down Friday morning, had dinner with Jenkens’ tax department at a Mexican restaurant, and spent the rest of the weekend in Dallas on Jenkens’ tab.

Hurley returned to Washington. A few weeks later an attorney from the Dallas firm of Hughes and Hill called her at work. “We know you’ve been looking around Washington for work,” the lawyer began confidentially. Vester Hughes and John Glancy were going to be in Washington. Would she be willing to have dinner with them? Hughes was the firm’s name partner, the most prominent tax lawyer in Dallas. Glancy was comanaging partner of the firm. Both were former Supreme Court clerks. Hurley agreed to have dinner. During the meal, however, she learned that the firm would not give her full credit for the two years she had spent clerking. So much for Hughes and Hill.

Finally, in the summer of 1984, Hurley called an attorney at Jenkens to accept the firm’s job offer for the second time. “For Jenkens, persistence paid off,” she admits. But Hurley’s glamour days are over. She spends most of her time like any other young associate, immersed in her chosen specialty. For Becky Hurley, that means the drama and excitement of tax law.

Fighting for Lawyers

Two years ago the Dallas firm of Johnson and Swanson began talking to Jenkens and Gilchrist about a merger. Representing Johnson and Swanson was John Johnson, the firm’s managing partner. Among the Jenkens representatives was Richard Freling, the firm’s highest-paid partner and a member of its management committee. When the merger talks between the firms collapsed, Johnson and Freling continued their negotiations privately. Johnson promised Freling more money, a seat on his firm’s management committee, and an assortment of other enticements. When Freling jumped ship, taking two partners and several clients with him, Freling’s partners saw him as a traitor; he had parlayed his role as their representative into a move that damaged the firm. But to the rest of the city’s legal community it was no big deal. Business was business.

Law firm recruiting no longer ends when associates sign on with a firm. Most firms are equally busy trying to entice top veteran lawyers to jump ship. That is a revolutionary departure from tradition, which dictated that big-firm attorneys spend their entire careers where they began. “People did not move,” explained one Dallas lawyer. “Law firm partnerships used to be like marriages used to be.” Many young attorneys now see big firms merely as training grounds, places to stay for a few years and learn a lot, before you strike out for somewhere else.

Firms don’t wait for attorneys to submit résumés. Instead, they go after lawyers themselves. In 1983 the Texas management of Jones, Day, Reavis, and Pogue decided the firm needed to hire an expert in the tax consequences of public bond issues. A handful of partners sat down and drew up a list of ten top lawyers in the field, all employed by other firms; none had expressed any interest in working at Jones Day. Then, with the help of a professional headhunting firm, Jones Day began contacting lawyers to ask whether they would be interested in leaving their jobs. More than a year later Jones Day landed one of the names on its list: John McCafferty, a partner in the Dallas office of Fulbright and Jaworski.

Of course, the big firms remain selective about whom they will employ. Every big firm employs dozens of women, but both Houston and Dallas have been far less successful at hiring minorities. Houston’s Baker and Botts and Mayor, Day, and Caldwell employ the only 2 black partners at a Houston firm of 50 or more lawyers. VE has only 3 black associates among its 400 lawyers. Five of Fulbright’s 190 associates are black, and 2 of 155 at Baker and Botts. All the firms profess great distress at their inability to lure blacks into the ranks; Vinson and Elkins has even gone so far as to commission an internal study of the problem and to contribute $7000 to a minority scholarship program at UT. The problem, they say, is that the few black students who meet the requirements of top firms are heavily recruited. Invariably, they consider the East and West coasts more hospitable.

Hustling for Business

On the first Tuesday of every month nine partners in the law firm of Jones Day gather around a polished conference room table at their offices in Dallas. They are members of the firm’s client development committee, and their job is to bring home the bacon. Aggressive client development campaigns are a product of the new era. Hefty legal bills have prompted corporate clients to shop around for the best possible deal, in terms of both fees and service. Because the best clients no longer care who has represented them for generations, every firm can join in the scramble for their business.

Two popular approaches for soliciting business showcase the big firm’s expertise. The first is to send newsletters to potential clients on, say, changes in tax law. The second is to invite prospects to a luncheon seminar in a posh hotel ballroom, perhaps to hear the firm’s Austin lobbyist discourse on the impact of the recent legislative session. But many lawyers make overt sales calls on corporate decisionmakers, preferably over lunch. This summer the partner-in-charge of Baker and Botts’s new Dallas office was positively itching for the opportunity to make such appointments. “I’m somewhat frustrated, frankly, by the fact that I’ve got to spend so much time practicing law,” he said.

A company relocating to Texas can expect to be besieged by attorneys. High-profile business brings everyone running. When Dallas’ mass transit authority, DART, needed a general counsel, 32 law firms applied for the job. Each submitted long bids for the work, detailing the firm’s pedigree and pledging the attention of its most prominent partners. Two Dallas firms skilled in the ways of real estate offered a novel proposal: they would represent DART together, in a legal joint venture. All big firms employ at least some of the tactics that a previous generation of lawyers would consider heretical. But few firms have developed as sophisticated an approach as Jones Day.

Jones Day traces its origins back to 1893, in the faraway city of Cleveland. Now the nation’s fourth largest firm, Jones Day has offices in six cities. It came to Texas in 1981, after one of its largest clients, Diamond Shamrock, moved its headquarters to Dallas. The firm’s Cleveland brain trust quickly decided it wanted a major presence in Texas—a big office with dozens of attorneys and hundreds of clients. There was just one problem. Except for Diamond Shamrock, Jones Day didn’t have any clients in Texas. It established a foothold by buying out a small Dallas firm and starting with 25 attorneys. Today Jones Day has 122 Dallas lawyers and a bustling Austin office as well. To understand how the firm has grown, one must know what the nine Jones Day partners do each month around the conference table.

Mostly, they gossip. For several hours the lawyers trade intelligence about companies moving to town, beginning new lines of work, or showing signs of discontent with their present firms. Then they discuss the chances of winning each company as a client and, on that basis, assign each prospect a rating—high, medium, or low. Names of high-priority prospects are turned over to the committee’s full-time administrative assistant, who begins building a computer dossier on each. The assistant pulls out annual reports and proxy statements and pores through newspaper clippings and electronic data files. When she is finished she circulates within the firm lists of the target client’s key personnel. The client development committee needs to know whether someone—anyone—has a connection.

“We have somebody in Cleveland who probably went to law school with that guy,” says Jones Day partner Ron Kessler. When an entrée is identified and a meeting set up, a team of lawyers plans its presentation to the client. It will usually bring along a handful of the firm’s tastefully designed brochures that describe Jones Day’s experience in particular areas of practice.

When the meeting takes place, the lawyers are open about their goal. “Many times it’s very blunt: ‘We’d like to do some work for you,’ ” says partner Jim Baumoel, who runs Jones Day’s Austin office. “It’s a matter of not being afraid to call and say, ‘You need some good lawyers.’ ” While the implication is that the company’s present attorneys are not quite adequate, bad-mouthing is not allowed. Instead, the pitch is often preceded with faint praise for the competition. “We know you’re ably represented, but we want you to know what we can do.” At Jones Day, the opening strategy usually is to identify a single slice of legal work that is most likely to get the firm hired. “We try to determine the best opportunity to get our foot in the door,” says Baumoel. Once the firm is retained its attorneys will begin suggesting other areas in which they might provide representation. “Look, you’ve got a sizable operation here,” the lawyer might say to a real estate client. “Do you ever have employee problems? We have a terrific labor lawyer.” That is a practice known as cross-selling, just another marketing tool lawyers employ these days.

A few clients have shrewdly taken advantage of firms’ client lust by employing a counterhustle. Houston banks traditionally have used their loyalty to a single firm to encourage its attorneys to lease office space in their buildings. The tactic was well understood: you give your business to the guy who gives you business. Now Dallas banks that spread their business around have dangled the carrot of just a bit of their legal work to lure law firms into their buildings. Eager to please, firms already settled into downtown quarters have set up satellite offices in the bank buildings. It is no accident that among the 22 preleased tenants of the new 72-story InterFirst Plaza building are eight law firms—including Johnson and Swanson, which has its own building two blocks away.

The Tyranny of the Billable Hour

When Hugh Rice Kelly became general counsel for Houston Lighting and Power, he knew some changes had to be made. He knew that from personal experience. Kelly had represented—and had billed—Houston Lighting and Power for nine years as a Baker and Botts attorney.

Legal fees of up to $250 an hour for senior partners have spurred corporations to establish in-house staffs. Houston Lighting and Power, for example, which had no lawyers of its own before 1977, now has a dozen. By the end of the year those lawyers will handle three quarters of the utility’s regulatory work, all of which used to go to Baker and Botts. “On an hourly basis we can damn near cut the cost by a third or more,” says Kelly. “We’re saving millions of dollars a year.”

Corporations are also spreading their business around, hiring different firms for each transaction. Houston Lighting and Power, which traditionally gave Baker and Botts all of its work, in 1984 split its $10 million in outside legal business among 28 firms. (Baker and Botts still received the lion’s share, $6.2 million.) Says corporate convert Kelly, “It keeps their competitive instincts working in your favor.”

This environment has made billable time more crucial to large firms than ever before. It is part of a new cost-consciousness among lawyers, learned not to save clients money but to maximize profits. Firms even hire a new generation of law firm administrators, usually CPAs, who are paid an average of $100,000 to mind each penny. The big-firm lawyer’s life is dominated by a push to bill, bill, bill.

New associates are expected to charge clients up to at least 1800 hours a year—a schedule that forces them to work nights and weekends. For the client, that doesn’t necessarily mean better representation, just more representation. A mediocre attorney who bills far more than average stands a good chance of making partner; an unusually talented lawyer who falls short of his quota does not. Even partners, who customarily worked less and earned more as they aged, face new pressure to produce, for salaries are increasingly determined by personal billing totals.

When lawyers first started keeping time sheets, they were used merely as guides to help determine what to charge. Now there is rarely a subjective component in what a client is billed. At Dallas’ Akin Gump lawyers mark their hours on a special sheet of paper that can be read by an optical scanner. The scanner feeds information into a computer, which multiplies the numbers by the lawyer’s billing rate and spits out a bill. Invoices are sent out at month’s end, regular as clockwork. Says Johnson and Swanson’s John Johnson, “We bill every thirty days and expect to be paid monthly, like the phone company.” Most firms withhold paychecks to attorneys who fail to turn in their time sheets. At the 75-lawyer Houston firm of Chamberlain, Hrdlicka, White, Johnson, and Williams, lawyers who are late with their time sheets are fined $100 a day.

It is a case of caveat emptor. In this world nothing is free. Lawyers charge for meeting with one another, organizing their files, and the work of the firm librarian. Pick up the phone to chat briefly with your attorney, and you are certain to be charged for fifteen minutes. Agree to have him fly in from out of town, and not only will you pay for his expenses but you will also be billed an hourly rate for his travel time. Ask for copies of court documents, and you will be charged for photocopies and secretarial costs. In 1983 Baker and Botts even billed Houston Lighting and Power for the time it took to draw up a bill.

To maximize revenue from each attorney’s billable time, many big firms have become downright snooty about whom they will represent. Like Highland Park shops that snub commonly dressed customers, firms turn down work that does not allow them to charge a premium rate. “We produce Cadillacs,” says John Johnson. “We don’t produce Volkswagens.”

In the new age there is no room for a partner who does not carry his weight—even at a large firm. Dallas’ Akin Gump, whose Washington office is run by former Democratic party chairman Robert Strauss, supported partner Lee Simpson while he worked almost full-time as a member of the city council. During Simpson’s second term, managing partner Alan Feld advised him to take a leave of absence. “Every law firm can afford one politician,” Feld told Simpson. “No firm can afford more than one.”

And there is no time to do work that does not pay. The American Bar Association’s Code of Professional Responsibility states that every lawyer has an obligation to give away a portion of his time to the disadvantaged. The notion rests in the fact that lawyers have a monopoly on the right to argue in court; as a result, they have an obligation to provide those who cannot afford it with access to the courtroom.

None of the big Houston firms has an organized pro bono program. In Dallas only Hughes and Luce (renamed again after John Hill was sworn in as chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court), which single-handedly staffs a legal clinic for the poor, displays more than the city’s characteristic laissez-faire attitude toward the practice. A 1981 study by the State Bar found that only 7 of every 100 attorneys in Texas do pro bono work. The group estimated that Texas’ poor need help with 475,000 legal problems a year. The number of lawyers doing pro bono, plus lawyers for Legal aid and legal services groups, can handle about 42,000. In El Paso the backlog of poor people in need of representation got so large that in 1982 state judges issued an order requiring every lawyer to handle two pro bono cases a year.

Managing partners of large firms quickly say they do plenty of pro bono work, then cite their involvement with the chamber of commerce or the local symphony. It is an interesting notion of what constitutes the disadvantaged. Firms will allow the few young lawyers who want to do pro bono to do so but on their own time. Many East Coast firms permit associates to count a certain number of pro bono hours toward quotas for billable time; those in Texas do not. “The perception among younger lawyers is that their firms don’t want them to do this, and as a result, they don’t,” says a Dallas associate.

The Price of Change

The parallels between the early history of Dallas’ Coke and Coke and that of Houston’s Vinson and Elkins are striking. Both firms were dominated by strong-willed men who also ran the largest banks in their cities. But Vinson and Elkins is now the country’s eleventh-largest law firm, while Coke and Coke, an institution that dates back to 1881, has dissolved its partnership and closed its doors. What happened to Coke and Coke is important, for it confirms the demise in Texas of the old-fashioned legal practice. The firm’s story shows that in modern times a firm that refuses to change with the times will become a casualty of them.

Coke and Coke was founded when Henry C. Coke, a native of Virginia, came to Texas and opened a law office. Fourteen years later his younger brother, Alexander, joined him, and they began a practice together under the name of Coke and Coke. Through much of the century to come the Cokes helped establish many of Dallas’ prominent businesses. Among them was Magnolia Petroleum, later to become Mobil Oil, and Lone Star Cement.

The firm’s key client was First National Bank, Dallas’ largest bank and the predecessor of InterFirst. Henry Coke, who helped incorporate the bank, was a large shareholder and served for years as chairman of the board; his two sons served as directors as well. Coke and Coke was a family firm; at one time, it employed five Cokes. Henry C. Coke, Jr., joined the practice in 1929 and remained affiliated with the firm until his death in 1982. When John N. Jackson, now eighty and still practicing, was made partner at Coke and Coke in 1930 he was the only outsider. He served as comanaging partner with Henry Junior until 1973.

During the sixties Coke and Coke began to fall out of step with the times. The firm never promoted a woman to partner, and it never employed a minority attorney. While other firms began relying on computers, all bookkeeping at Coke and Coke was done by hand. The firm did not believe in strict hourly billing to determine fees. “You’d have a meter ticking like a taxi,” says Jackson. “It didn’t strike me as being very dignified for a professional man.” Despite its prominence in the city, Coke and Coke did not particularly care to grow. It served its traditional clients and whatever new ones might step through its doors. Since there was no need to seek new business, there was rarely a reason to hire lawyers. Seniority dictated compensation, so much of the firm’s profits went to old partners who brought little money into the firm.

It was not surprising, then, that Coke and Coke eventually found itself in trouble. The beginning of the end came in the early seventies, when First National stopped paying Coke and Coke an annual retainer and began sending some of its work to other firms. More and more of the business went to the fast-paced firm that would become Johnson and Swanson, whose founding partners included three Coke and Coke associates. Coke and Coke was no longer an attractive place to work. Between 1968 and 1974 the firm averaged two new associates a year. By 1980 partners outnumbered associates by almost two to one—the reverse of a healthy firm’s structure.

Henry Coke, Jr., and Jackson stepped down as comanaging partners in 1973 and retired to senior statesman status in 1978. A new management committee of younger lawyers made a final attempt to breathe new life into Coke and Coke. They stepped up recruiting, and the firm grew to 43 lawyers by 1981. A merger with Fulbright and Jaworksi was all but sealed a year later. But when the Houston firm took a close look at the Dallas firm’s books, it backed off. In 1983 the firm announced a strict nepotism policy. Repudiating its history, Coke and Coke stated in its recruiting material that it would not employ any lawyer with a relative at the firm. But that was all too late. By early 1984 Coke and Coke was down to 25 lawyers. Attempts to merge with other firms got nowhere. Last year the firm’s management committee issued a public statement announcing that Coke and Coke would shut its doors, effective October 31, 1984.

The firm’s dissolution was handled as cordially as such a matter could be. Everyone associated with Coke and Coke was paid everything he was entitled to receive. John Jackson was saddened by the news but was welcomed by another Dallas firm, Carrington, Coleman, Sloman, and Blumenthal.

In many ways Coke and Coke, for refusing to change, brought failure upon itself. But certain values the firm upheld are worth noting before they vanish entirely. The legal world was fast becoming populated by specialists; Coke and Coke, like family practitioners, tried to provide general services. “When I started practicing law, a lawyer would try a case today, draw a will tomorrow, and charter a corporation the next day,” says Jackson. “If you had a license to practice, you just did everything.” The firm did much of its work on retainer, billing some clients only once a year. Under that arrangement, the client had no hesitancy to call his lawyer. The firm never sued to recover an unpaid bill. Nor did Coke and Coke charge all clients using the same lawyer the same fee. The widow with the modest estate naturally paid less than the corporation with billion-dollar assets. Often, Coke and Coke provided free legal services. “The profession of law is a monopoly,” says Jackson. “It imposes on the lawyer the responsibility for getting legal services to everybody who needs it. Everybody there was doing some kind of pro bono work for a charitable organization or people who couldn’t afford to pay.”

Despite the death of Coke and Coke, John Jackson retains a belief in the law that few young attorneys share. “The law really is a profession,” says Jackson. “That word has meaning, real meaning. You’ve got to make a decision at some point as to whether you’re going to be a lawyer or a businessman. I don’t mean lawyers ought to run a law office without keeping books. But to the extent that law is operated for profit as its primary object, it is incompatible with the professional responsibilities of a lawyer.”

The Pick of the Perks

Sure, a corporate lawyer works long hours under terrific pressure. But look what he gets for it.

The Summer Clerk: Your salary will run about $750 a week, but you won’t need to pay for much. Vinson and Elkins, for example, will subsidize your housing, rent you a car, and provide free parking at work. You’ll get a private office, perhaps with your name on the door, and share a secretary. But don’t worry about work too much; clerks average fewer than forty hours a week. You’ll spend an hour or two (or three) each day being taken to lunch. After work enjoy an endless round of parties and social events. No one wants you to get flabby; several firms provide free health club memberships.

The New Associate: The hours are long, but the rewards are great. In 1985 the starting salary at a big firm was about $47,000 in Dallas and $40,000 in Houston. Take paid time off to study for the bar exam; the firm will pay for your review course, your exam fee, and your bar association dues when you pass. Fussy about furniture in your private office? If you work at Dallas’ Johnson and Swanson, you’ll get a $4000 decorating allowance. Insurance benefits—health, dental, life, and, of course, malpractice—are generous. If you’re hired at VE, you’ll feel like a big-time businessman, thanks to an automatic $5000 letter of credit. For women attorneys, J&S offers a four-month paid maternity leave. Take two- to three-week vacations at most firms, four weeks at Dallas’ Jones Day. And if you’ve signed on with Dallas’ Jenkens and Gilchrist, you can spend your time off in the firm’s Hawaii condominium, which overlooks Waikiki Beach.

The Partner: In Dallas your salary will jump to about $100,000. If you work at VE or Baker and Botts in Houston, you’ll make $150,000. Pay will climb rapidly, depending on your production. At one high-powered Houston firm, attorneys ten years out of law school averaged $205,000—more than Ronald Reagan makes. Those twenty years out make about $370,000. Top senior partners in Dallas make $500,000. Those at B&B make $600,000, and the two top partners at VE—Howard Baker and managing partner Evans Atwell—earned $750,000 last year. But the most important partner’s perk is power. Instantly, you gain a voice in every important firm decision. You will know how much your partners produce and what they earn. You will vote on whether to raise or lower their salaries. Most of all, you will help to decide which associates to promote to partner. You will help select the new members of the club.

One Big Bill

Yes, you pay for the lawyers. But in a giant lawsuit you pay for PR consultants and paper shufflers too.

The giant law firm lives and breathes to handle the megasuit—the kind of complex litigation that allows attorneys to bill without mercy. There’s no better example of this phenomenon than the four-year-old battle over the South Texas Nuclear Project. That matter pitted the owners of the STNP—Houston Lighting and Power, Central Power and Light, and the cities of Austin and San antonio—against the original contractor for the nuclear plant, Brown and Root of Houston. The owners alleged that Brown and Root’s shoddy work had resulted in billion-dollar cost overruns.

The suit was filed in December 1981. It has not gone to trial and probably never will; the two sides have reached a tentative $750 million settlement, which awaits approval by the Texas Public Utilities Commission and acceptance by the City of Austin. The price of fighting a legal battle that never went to court: more than $100 million.

Why are such cases so expensive? First, they invariably involve a preposterous number of attorneys. In September 1984 a judge in Matagorda County held a hearing to dispose of some routine motions in the lawsuit. Attending the proceedings were thirty lawyers—from twelve law firms. Houston Lighting and Power was represented by Baker and Botts, with a delegation of five lawyers. A Corpus Christi firm represented Central Power and Light with three. San Antonio sent two attorneys from a local firm, and Austin sent two, one from a Michigan firm and the other from Fulbright and Jaworski. That’s twelve attorneys—on the same side. Not to be outmanned, Brown and Root and its parent company, Halliburton, had eighteen lawyers —including nine from Vinson and Elkins.

Through last June Houston Lighting and Power’s legal bill in the case has totaled $10.4 million, including $5.9 million that went to Baker and Botts, while Central Power and Light has paid legal fees and expenses of $2.2 million. San Antonio’s bill is $12.4 million; Austin has paid close to $6 million. Brown and Root, on the other side, had not revealed its total expense, but it has estimated that its monthly cost for the litigation has climbed to as high as $2.5 million.

Support services for the litigation have cost the plant owners even more than the lawyers, a total of $33.2 million. To organize the 50 million pieces of paper involved in the case, for example, the plaintiffs have employed aspen Systems Corporation. The cost: $12.7 million. The modern lawsuit also requires outside experts—in this case, 45 consultants, including four accounting firms, college professors, economic forecasters, PR men, and engineers.

Then there are miscellaneous costs. Adding to the bill is former presidential press secretary George Christian, whom Brown and Root hired to handle its public relations. One day before the company submitted its testimony to the PUC last august, Christian orchestrated a dog-and-pony show for the press at VE’s Austin offices. A parade of experts and lawyers participated in the session, prompting one reporter to remark that the hired help was probably charging the company $100 an hour. Brown and Root president T. Louis Austin corrected that impression. “If you think these folks are charging us only a hundred dollars an hour,” Austin told reporters, “you people are pikers.”

The Specialty Shuffle

Woe to the lawyer who misreads the latest legal trends.

What’s Hot

• Takeover work. During the billion-dollar takeover war between Coastal and Houston Natural Gas, Vinson and Elkins had 92 attorneys working on behalf of Houston Natural Gas. The result of all this fabulously expensive legal warmongering? Nothing. After ten days of battle in the Wall Street trenches the two sides agreed to drop their bids for each other. Baker and Botts made $3.3 million working for T. Boone Pickens in 1984. “The truth is, you can’t charge enough for a client to care,” a prominent refugee from one of Houston’s top firms says of takeover work. “Your conscience stops you before the client does.”

•Municipal bond work. It’s low profile but even more consistently profitable. Vinson and Elkins dominates this specialty. Firms charge a percentage of the total cost—usually 0.6 per cent to 1 per cent, so a week or two of work on a $100 million bond issue can mean a fee of up to $1 million. And Texas is the nation’s top issuer of municipal bonds. Especially hot: industrial revenue bonds. New tax laws may make IRBs less attractive by year’s end, so everyone’s rushing to get in under the wire.

•Bankruptcy work. “A blind dog could practice bankruptcy law these days,” says the managing partner of one of Houston’s Big Three.

•High-tech law. A speculative market. Bullish firms are creating special “intellectual property” and technology sections.

•Financial services. Smart firms are anticipating a major shakeout in the banking and S&L industry. The result: dozens of lucrative merger and acquisition deals.

•San Antonio. Fulbright and Jaworski and Akin Gump have both opened up Alamo City offices. VE is considering one.

What’s Not

•Insurance defense work. Insurance companies are setting their own ceilings on legal fees, making them only slightly more popular as clients than neophyte oilmen. The big loser: Fulbright, a firm built on insurance defense work. Baker and Botts bailed out of the business years ago, dumping clients it had represented since before World War I. Insurance work is where bill padding is most common. When insurance companies impose billing ceilings 35 per cent below a firm’s standard rate, some lawyers nod their heads and simply bill 35 per cent more hours.

•Oil and gas. Dying—like the $40 barrel. Shrewd energy lawyers have changed specialties. Those who remain spend their time restructuring their old energy clients—or advising them in bankruptcy.

Top-Dollar Clients

Big law firms represent your city, your hospital, even your garbage collectors.

Firm

Hourly Billing Rate (Junior Associate–Senior Partner)

A Sampling of Top Clients

HOUSTON

Baker and Botts

$50–$250

Gerald D. Hines Interests, Houston Lighting and Power, Mesa Petroleum, Pennzoil

Butler and Binion

$70–$200

Allied Bank of Texas, Armco, Hobby-Catto Interests

Fulbright and Jaworski

$60–$225

Bank of America, Browning-Ferris Industries, City of San Antonio, City of Austin, Coastal Corporation, Aetna Life and Casualty, Houston Post, Texas Medical Center

Mayor, Day, and Caldwell

$65–$200

Dean Witter Reynolds, Lloyd’s of London, Metropolitan Transit Authority, Mischer Corporation, United Financial Group (United Savings)

Vinson and Elkins

$65–$210

First City Bancorporation, Texas Eastern, Halliburton, Hermann Hospital Estate

DALLAS

Hughes and Luce

$60–$225

Electronic Data Systems, Harte-Hanks Communications, MCorp, Lomas and Nettleton

Jenkens and Gilchrist

$70–$185

Dallas Cowboys, BancTexas, Dallas area Rapid Transit, Murchison Brothers

Johnson and Swanson

$70–$250

Hunt Oil, InterFirst, American Airlines, Cadillac-Fairview Development

Jones, Day, Reavis, and Pogue

$75–$265

Trammell Crow Company, Diamond Shamrock, Bright Banc, Central and South West Corporation

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas