When the then president of Pakistan, Pervez Musharraf, made a first trip to the United States in 2006, he stopped in out-of-the-way Paris,Texas, to visit an old friend. The friend was Arjumand Hashmi, a renowned cardiologist who evaluated Musharraf and pronounced him “in excellent health.”

Six years later, Hashmi is now a year into his term as the mayor of Paris. As Anand Giridharadas of the New York Times reports in a profile of the small-town mayor this week, Hashmi is perhaps Texas’s most unlikely mayor–not just because he has foreign friends in high places but also because he still practices medicine full-time and is a Pakistani-born Muslim in a city where, as Giridharadas observes, there are “more antiques shops than restaurants and more churches than both of those things combined.”

“He is like the opening line of a joke: So a Texan, a Muslim, a Republican, a doctor and the mayor of Paris are sitting at a bar…” Giridharadas writes of Hashmi. “Except that he is, by himself, all the people in the joke.”

Hashmi acknowledges he is an outsider in overwhelmingly white and Christian Paris, but he welcomes the recognition, and it is one of two important tactics that have upended his initial perception as a threatening newcomer who some Paris residents accused of running to drive Christianity out of the city. In Paris, where he is nobody’s old friend or nephew, he has orchestrated an end to nepotistic “brother-in-law” deals that award contracts and deals to unfit relatives.

The other factor that has propelled Hashmi’s rise has been hard work. He often stops by local agencies unannounced during lunchtime and has worked to beautify the city, all the while continuing to practice cardiology and run a local hospital catheterization laboratory–a balance he has achieved by waking up at 3:30 a.m. every day and, in one instance Giridharadas observes, evaluating patients in the hospital after 11 p.m.

That “immigrant’s zeal” Hashmi has been occupying the office with has earned the mayor the admiration of even the most previously-alarmed Paris residents. Some townspeople Giridharadas interviewed described the mayor as “a blood transfusion” or “a breath of fresh air.” Meanwhile, the City Council voted 7-0 to reelect him this year, an unmistakable display of confidence in a man who was voted in by a count of 4-3 in his first election.

The zeal and the approval also have Hashmi pondering a run for a national office, a possibility that seems improbable without minding the speed with which Hashmi has convinced Paris. Giridharadas writes:

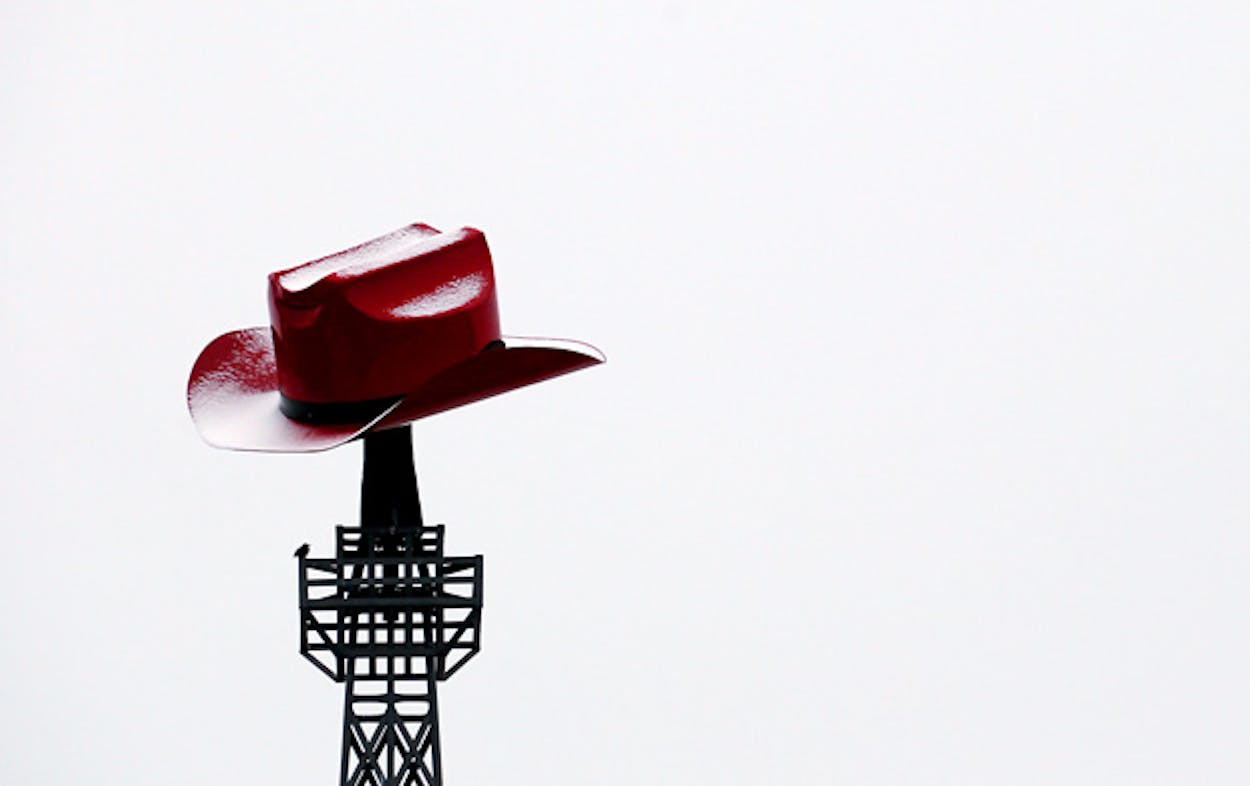

“But wherever he ends up, Dr. Hashmi may have a unique opportunity to build bridges in an age of deep divisions: he is, after all, a brown Muslim voted in with the support of droves of white Christians; a Lamborghini-rich doctor born in one of the poorest places on earth; a cowboy boots-wearing Texan who is also a Yale-trained jetsetter; and an American who has close friendships with the leaders of Pakistan, with which the United States has a hard, fraught relationship.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy