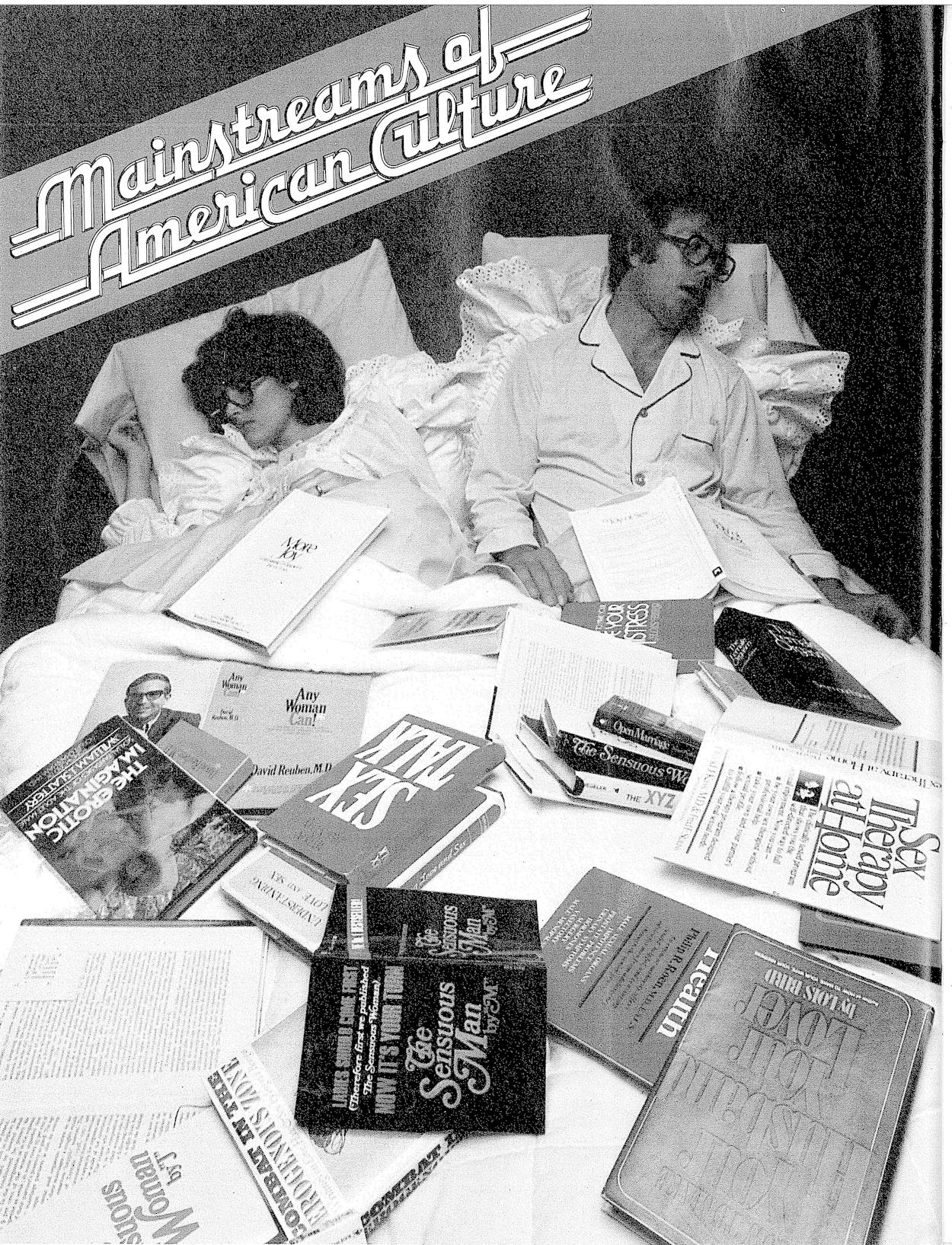

The Joy of Sex and More Joy lie beside my desk. They are the base of a column of books, all written to instruct the American people about sex. When I finished reading each book I placed it carefully on top of the one before; now they reach from the floor almost to my navel. That column of books, Doric in its simplicity on the outside but a baroque mass of conflicting ideas on the inside, is nevertheless a monument to one fairly simple and obvious truth: We must be told. We can’t figure sex out for ourselves. Our instincts aren’t that explicit anymore. Monkeys raised in isolation never learn how and instinct has a stronger grip on monkeys than on us. We learn about sex, not by being instructed by a family member or watching older members of the tribe, but by reading. We now depend upon books, of all things, for the preservation of the species.

I don’t think it’s any more disturbing or unnatural that we should be the only animal who learns sex from books than it’s disturbing or unnatural that we have language and must learn to speak. But there is something beyond curiosity about the facts of life that prompts more than 3.2 million people to buy The Joy of Sex and similarly large numbers to purchase Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex, The Sensuous Woman, The Marriage Art, and quantities of other books, perhaps not as notorious as these and now generally forgotten, which sold almost as well in their day.

Sex manuals have always been in the vanguard of sexual attitudes. It is easy to forget nowadays, with the title of a pornographic movie so well known it is part of the lore of a president’s fall from office and Linda Lovelace a name as recognizable as that of any other movie star, that public attitudes about sex have changed more in the last fifteen years than they did in the previous fifty. I can remember being given the job, as part of the hazing during my freshman year in college in 1962, of finding a stag film—the real thing and nothing less—to show at the party that marked the end of our initiations. I spent the better part of a week lurking around the seedier parts of Houston and sidling up to managers of novelty stores, strip clubs, run-down movie houses, and newsstands and asking in an undertone if they knew where I could get a dirty movie. I never found one. My face was saved only by a roommate who arrived back from Mexico in the nick of time with a film he’d bought in Nuevo Laredo. It turned out to feature two people with porcine bodies wearing only black masks and white socks; all the good parts had been spliced out. This caused a general depression from which the party never recovered. Two years later I was called into the dean’s office for having kept a girl out all night after she had gotten permission from the school by saying she was going to be with her parents. Only by my passionate and repeated insistence that this circumstance, though suspicious, had been entirely innocent—it had and hadn’t been; had not been in intent, had been in result—was I able to escape whatever punishment was in store for me. Now, of course, there’s no problem finding pornographic movies in Houston or anywhere else and college students can simply spend the night together in their rooms without going through elaborate ruses or incurring the wrath of the dean.

Well, I am, I suppose, in favor of all that. I don’t believe in censorship and no censorship means there are going to be pornographic movies. I think that, with very few exceptions, there shouldn’t be any laws against sex between adults and, at eighteen, college students are adults. In a general sense, I suppose I’m for almost everything that could be listed under the heading of the sexual revolution or, more precisely, I am against the measures that would have been necessary to stop it. Undoubtedly, the sexual revolution has helped get rid of that garbage heap of sexual prejudice and misinformation left over from the Victorian age. That mess needed to be cleaned up, and it took the great changes we have seen in sexual attitudes to do it. Marriage manuals, which is what sex manuals used to be called, have certainly played their part in that cleaning-up and, for whatever good has come from it, they deserve their share of the credit.

But the garbage heap is nearly gone, a fact recent manuals have failed to see. We’re on our own these days. Neither laws nor social opinion are especially restrictive. Or especially helpful. Obviously we don’t know what to do with the freedom we’ve won or else we wouldn’t all be buying every book that promises to help. But sex manuals, which once made things seem so clear, are now only adding to the confusion. There are, they tell us, still more problems we need to solve and still deeper repressions we need to be rid of. They even mock us, as we shall see later. First though, it’s necessary to take a step back and see how things that took so long to straighten out got mixed up again so soon.

Reading through Victorian books on sex is a very good way to have a few sly, rakish laughs. They were written by the scientific experts of the day and the more certain the expert, the funnier he is. Science in its popularized forms seems never to be so certain as when it’s wrong. We should all, if the world were only just, have the natural right to live long enough to see Dr. Reuben, author of Everything You Always Wanted to Know, or Alex Comfort, editor of The Joy of Sex, as the same sort of comic book pundit that we now see, say, Sylvester Graham to be. Graham was a popular nineteenth-century author and lecturer who believed that sex was taxing to the constitution. If sexual desires were indulged too frequently, the result would be physical debilitation. Graham thought sexual desire and all other threats to good health could be cured by the proper diet. To save the world, therefore, he concocted a food that, besides being healthy in other ways, would reduce sexual longings. That cure, the Graham cracker, proved so effective that it is still available to those longing souls who need its several benefits.

Not until the end of the nineteenth century did ideas about sex change significantly. Before then sex was considered proper only when used for procreation, but by the early 1900s the idea that sex could be recreation, too, had thoroughly taken hold. Contemporary sexual literature announced, with or without woeful commentary, that the desire for children was no longer as strong as the desire for sex. Marriage manuals responded to this change by an increased emphasis on skill. Professor Michael Gordon of the University of Connecticut has the distinction of discovering that the first mention of mutual orgasm, an occurrence by which later books would insist one’s sex life be judged, was in George W. Savoy’s Marriage: Its Science and Ethics, published in 1900. In 1919 came H. W. Long’s Sane Sex Life and Sane Sex Living, with one of the first detailed descriptions of sexual technique. And inevitably, with sex being pursued for pleasure rather than procreation, a few manuals appeared after 1920 which, though they did not necessarily condone sex before marriage, nevertheless omitted the previously obligatory condemnation of it. But no manual published during those years understood the changes that had happened so well, caught the spirit of the times so perfectly, or had a greater influence than Ideal Marriage, a book by a Dutch gynecologist named Theodoor Hendrik Van de Velde.

Ideal Marriage appeared in Europe in 1926, was published here in 1930, and has been in print ever since. In America it has sold almost one million copies, but its importance goes beyond any simple accounting of sales and printings. Plenty of other books have sold more, and some from the same period—A Marriage Manual by Drs. Hannah and Abraham Stone is one—have also been reprinted year after year. The other books have their virtues. The information in A Marriage Manual is dependable and clearly presented, the advice is sensible and straightforward. But Ideal Marriage has vision and the others don’t. In A Marriage Manual a young couple about to be married visit a doctor to receive his instructions about sex. Their questions and his answers form the book. The doctor is so extremely sensible, sane, and correct that he seems never to have done anything foolish or taken any chances, even in love, and his advice seems to ignore something indefinable but terribly important. Compare the doctor’s first words to the young couple—“I shall, of course, be glad to give you whatever information I can. An understanding of the basic physical, psychological and social factors involved in marriage is definitely a great help toward a more satisfactory adjustment”—with Van de Velde’s first lines in Ideal Marriage—“I show you here the way to Ideal Marriage. You know the honeymoon of rapture. It is all too short, and soon you decline into that morass of disillusion and depression, which is all you know of marriage. But the bridal honeymoon should blossom into the perfect flower of ideal marriage. May this book help you to attain such happiness.” Yes, it’s florid. The whole book is florid. It seems even more so here because Van de Velde is not, as he usually is, describing a specific caress or position or point of physiology. Yet his style, in spite of its romantic quaintness, is still, after all is said and done, beguiling today. It sounds fresh, unashamed without being jaded. Modern manuals don’t. By the Sixties sex manuals began to sound self-congratulatory for escaping the repression of the past and strident in their insistence on new freedoms; by the Seventies they were cool and self-satisfied. But Van de Velde writes like a man in love with love who wants to inspire his readers with his vision. No other manual writer comes close to matching his genuine tenderness.

Van de Velde was also the first manual writer who had the modern sensibility about sex, who thought that it was the basis of personal happiness, that it possessed pleasures that could be profound, that those pleasures were for both the man and woman equally, and that the way to those pleasures was through understanding and technique. Therefore he described technique. He included long discussions of the sexual aspects of smell, sight, hearing, taste, and touch. He was the first writer to recommend ways for the woman to arouse the man and also the first to recommend what he, ever delicate, called the “genital kiss.” He had a powerful vision of how sex should proceed, so powerful in fact that his instructions, at least in broad outline, have been copied by nearly every writer since: foreplay lasting long enough for the woman to become fully aroused, a variety of positions, a simultaneous orgasm (although some modern writers no longer consider this so important), and maintaining a closeness afterwards while passion subsides. That is, in book after book, the sexual model we are given; it is Van de Velde’s. He is the one, really, who has taught us how. In this respect he has probably had more influence, direct or indirect, on our private habits than any other writer of any kind in this century.

After Van de Velde there was increasing talk of sexual “artistry” and, through the Thirties, an increased fascination with positions. The ability for mutual orgasm gradually became recognized as the final criterion of good sex, the infallible sign of ultimate rapture. But the social context for all this remained marriage, a kind of marriage that from the outside would look exactly like a nineteenth-century one.

But after 1948, when Kinsey published his Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, it was obvious that this idyllic marital communion, even when it was possible, represented only a very small portion of American sexual activity. Actual behavior proved to be so far different from prescribed behavior that now, almost 30 years later, we have still not recovered from the shock.

Two things are important to remember. First, old ideas die hard. Just because people acted as they did in private didn’t mean that the old public strictures against things like infidelity, visiting prostitutes, and masturbation had less currency. This gap between what was approved and what actually happened was bridged most often, at least in sexual matters, by guilt.

The second thing to remember is that we had just emerged from a great Depression and won a great war. Society had withstood its most severe test. Kinsey’s first report would reveal the man of that society acted in ways that should have caused—if the warnings of the old strictures were true—the collapse of that society even without war: 40 per cent of married men had been unfaithful, 70 per cent of all men had visited a prostitute, 86 per cent had had premarital intercourse by the time they were 30, and virtually all had masturbated. Thinking back on their own sexual peccadilloes, many must have thought, “So many have done what I’ve done. The world is not in shambles. Why should I feel guilty?” Marriage manuals, in their titles—Love Without Fear, Sex Without Guilt—and in their pages, began to treat guilt as an enemy of sexual fulfillment and to assure their readers they needn’t feel guilty anymore.

But that wasn’t the only or even the most important effect Kinsey had on marriage manuals. Kinsey’s goal was to be scientific in attitude, to be completely nonjudgmental, and to look at sexual behavior as it actually was. He wanted to consider a sexual occurrence as a simple fact, just as gall wasps, Kinsey’s earlier scientific enthusiasm, were a fact. To do this meant that the social context in which sex occurred had to be ignored. The clear message of his findings was that, since each taste is to a greater or lesser degree different, the proscriptions against sexual activity should be very few. Since the report, the general tone of sex manuals has changed from that initial assurance that various acts aren’t bad to the recent insistence that virtually everything people can do is good.

Things have been taken to this extreme so quickly that books written after 1948 but before 1965 already sound as quaint, if not so wrongheaded, as nineteenth-century manuals. The change is especially apparent in manuals written by women for other women. The relaxing of censorship does not completely account for the differences between, say, Maxine Davis’ popular The Sexual Responsibility of Woman, published in 1956, with its carefully reasoned and reassuring chapters on “Preparing for Marriage” and “The Honeymoon,” and “J” ’s The Sensuous Woman, published in 1969, with its enthusiastic chapters on “Nibbling, Nipping, Eating, Licking, and Sucking” and “Party Sex—Swapping and Orgies and Why It’s Better Sometimes to Bring Your Own Grapes.” And in 1976, even “J,” the completely dirty girl, once such a compelling male fantasy, now seems to be obvious, ordinary, and unimaginative. I was ready to dismiss her simply by noting that her chapter on “Sexual Ethics” is just over a page long while her chapter on “Masturbation” is fifteen. But I was less inclined to be snide after realizing that The Sensuous Woman is the only contemporary book I read with any direct mention of ethics at all. The best The Joy of Sex could do was to suggest that if you are pleased to see the person you wake up with, you’re “probably onto the right thing.” Of course this is no help at the time. The problem is whether there is any way to know beforehand.

“J” ’s code isn’t much—in brief: if you don’t like a man, you mustn’t; if you do like a man, you may, unless he belongs to your sister or best friend; and no fair teasing unless you mean to go through with it—but she at least had the insight to know a code was necessary these days. As she says in another chapter, “It’s no longer a question of ‘Does she or doesn’t she?’ We all know she wants to, is about to, or does. Now it’s only a question of how tastefully she goes about it.” That’s a very good question, indeed, although tastefully may not be quite the right word. It’s close, however, because it implies good judgment and discretion, two difficult virtues which, in the modem sexual climate, have been replaced by that easy attitude—acceptance.

The Sensuous Woman is a book that tells other women how to “be” something that will, in theory, improve their lives. Maxine Davis’ previously mentioned The Sexual Responsibility of Woman and Dr. Marie N. Robinson’s The Power of Sexual Surrender (1959) are books that tell women how to “get” what will make them happy, and in both books that something is an orgasm. Sexual Responsibility begins confidently: “Woman has come of age. For the first time in the history of civilization she . . . can live her own life to suit herself.” But this new independence comes hand in hand with the “woman’s responsibility for sexual participation.” That means she must take responsibility for her own orgasm, a responsibility she can’t shirk, since her orgasm is the sign of a proper and healthy sex life and the cornerstone of a good marriage. She must tell her husband what she likes, she must suggest new positions and practices, and, if “her husband reaches his peak ahead of her the wife should never exhibit dismay or disappointment but should go right ahead and take whatever steps are then possible to effect her own orgasm.” There was even a warning, touching to me, that the bride on her honeymoon should be careful not to do anything to bruise her husband’s tender, masculine sensibilities.

The Power of Sexual Surrender, which sold so well it went through at least ten paperback printings, also begins on a note of confidence: “Happiness between men and women has never had such a radiant outlook as it has in this decade.” But there is something marring this outlook. Dr. Robinson claims that frigidity, which she defines as “the inability to enjoy physical love to the limits of its potentiality,” is a problem with over 40 per cent of American women. Given Dr. Robinson’s view of what the ultimate potential of physical love is, I suspect that the percentage must be much higher. She would have the woman embark on a program of complete submission to the male, which is supposed to result in this final moment: “In the woman’s orgasm the excitement comes from the act of surrender. There is a tremendous surging physical ecstasy in the yielding itself, in the feeling of being the passive instrument of another person, of being stretched out supinely beneath him, taken up will-lessly by his passion as leaves are swept up before a wind.”

The notion that women should be completely submissive is currently enjoying a certain vogue in some quarters (see “Retreat from Liberation,” Texas Monthly, June 1975). Otherwise Dr. Robinson is something of an anomaly since she believes quite literally in Freud’s view of female sexuality. Freud thought that women had two kinds of orgasms, clitoral and vaginal. The clitoral was essentially immature, adolescent, masturbatory, and a stage which she must abandon. The ability for and preference for vaginal orgasms was the mark of a woman who had developed fully. Without them she remained immature, her personality incomplete.

Today, the preponderance of evidence indicates there is only one kind of orgasm for women, but Freud’s real point was that vaginal orgasm was preferable because it implied orgasm during intercourse. This view—that the ability to have orgasm during intercourse is necessary for the woman’s personality to develop properly—-became the predominant one in manuals published from the Twenties until the very recent past. The writers used it as a way to define normality. Starting with Van de Velde, the advice in most manuals was anything that did not cause pain and led to intercourse was normal. Van de Velde, for instance, endorsed his “genital kiss” as a prelude to, not a substitute for, intercourse. The reason wasn’t that other acts were immoral, but that they reinforced infantile aspects of the personality that would prevent proper growth and eventually undermine the marriage. The frequent insistence in marriage manuals that the man should take care to give the woman an orgasm and that the woman should take care that she gets one came from the belief that her failure would be ultimately fatal to their love.

Undoubtedly this view has done much harm. It has made the male feel that he is judged solely by his performance on this point alone, and made the woman feel that she is failing when she can’t respond “totally.” The tension created by the man trying to make it happen and the woman trying to let it happen has surely caused plenty of bad nights throughout America.

The woman’s orgasm is still a mystery. No one knows, really, what it is, what it’s for in a biological sense, what psychological factors inhibit it, which factors ease it. Some biologists believe that the female orgasm is so confusing because it is going through rapid evolutionary change. In any event, all this stern insistence in the marriage manuals has probably not done much more to promote orgasms than would the simple suggestions to slow down, relax, and let passion build on its own. And the tyranny of the orgasm, as one writer called it, has, during the six decades that it’s held sway, certainly caused its share of guilt and feelings of unworthiness, the very things for which those same sex manuals condemn narrow Victorian morality. The orgasm, evidently, is no more benevolent a despot than the spinster.

Current manuals say there’s no such thing as normal and anything that happens between us freewheeling consenting adults is permissible. At the same time, we are led to expect much more from the orgasm than just a balanced personality: “The orgasm,” says The Joy of Sex, “is the most religious moment of our lives.” That apotheosis is accompanied by an array of techniques which, since there’s no such thing as normal, are all equally religious. We readers are supposed to sort through them to find the ones that will carry us closest to heaven.

Unfortunately for me, the most religious moment of my life was when I almost drowned. That may have left me permanently altered. But I can’t help feeling that there is such a thing as normal and that there are reasons for recognizing it, especially in a society where sex is going to be free and easy. Even a loose definition of normal would let one know what to expect from someone new and would give a certainty to the way of going about sex that is lost with too much hopeful groping among exotic possibilities. The normality described in sex manuals of the recent past, one predicated on simple intercourse, may have had its drawbacks, but at least it let lovers know where they were heading, and the final goal was easier to comprehend and much easier to achieve than a religious experience. And there was a comforting biological rightness to it, too. One was so obviously in the mainstream of human experience. One understood what was trying to be said.

If one thing has confused us more than any other, it is the exaggeration of the rewards of sensual experience. This has been going on for quite a while, but by far the worst offenders are The Joy of Sex and More Joy. I have already mentioned that according to them the orgasm is supposed to be “the most religious moment of our lives”; there are related proclamations throughout both books. Some are just silly: “People who soak together [in a hot tub] behave as if they’d shared a warm womb.” Others reinforce persistent myths like the whore with a heart of gold: love can be the “relationship between a prostitute and a casual client where, for reasons they didn’t quite get, real tenderness and respect occur.” And still other statements claim there can be nothing personal between people except sex: “Sex is the one place where we today can learn to treat people as people.” “All human relationships are sexual, even when they don’t look it and don’t involve the genitals.”

None of this, however dumb, would be so bad if it were not combined with the assumption that sexual abilities are the distinctions that separate good people from bad. Prejudice, self-congratulation, and contempt run all through the two Joys. We are informed that “Catholics have hang-ups over sex.” We learn that black sexual superiority is a myth because the only thing blacks are naturally better at than whites is “hiding on a dark night.” But then, in the next paragraph, we learn that, after all, blacks are better at sex “for the same reason they dance much better.” But the people the authors really hate are the ones they label Squares.

Squares include “business executives” and other “up tight,” “middle-class” people who, by definition, have less human feeling than the authors of Joy: “If your widened self-experience and experience of others leave you an unreconstructed Middletown don’t-carer, it wasn’t widened enough or human enough.” Of course the only self-widening experience is sex. Its effects are so powerful and so cleansing to the soul that no one who’d had really good sex would remain square for long. Instead they’d become an “environmentalist” or choose to “stay and make love rather than kill Vietnamese,” as if making love could have beat the draft.

The whole notion of love in the two Joys is based on contempt for everyone else: “The finger-raising quality of lovers vis-a-vis society is as necessary psychologically as their tenderness to each other.” And lovers remain isolated because the “best modern sex is nonreproductive . . . sexual freedom isn’t compatible with a child-bearing life style.” Children, after all, necessarily make a family and families necessarily make a society and a society, admittedly, creates “money-grubbing”—since families must be fed—and “power-hunting”—since society must be governed—both middle-class “perversions” that sexual freedom is supposed to cure.

While we are on the subject of money-grubbing, I think there’s something else worth saying. Any number of readers who were familiar with Alex Comfort’s earlier writings—clear, learned, sensible, even wise; the object of admiring essays by the likes of Anthony Burgess—have wondered what happened to him, how he came to represent a project like Joy. I think he knew exactly what he was doing. In his 1966 book, The Nature of Human Nature, he comments, “If this book were about sexuality rather than about human biology it would be necessary to print many times as many copies.” Of all money-grubbing middle-class perversions, which could be more calculated and cynical than The Joy of Sex? While it’s depressing that over 3.2 million Americans have bought this book, it’s reassuring at least that no one who takes it seriously is going to reproduce.

Ever since the turn of the century the most influential sex manuals have had a crusading zeal. The authors have believed that sex was a healthy, pleasurable, necessary experience. They have tried to wean their readers away from notions to the contrary by calming their fears and by claiming for sex the self-expressive and illuminating and binding qualities that it definitely has. But to read how current manuals rail against the overwhelming sexual repression in the United States today, you would, if you didn’t know better, believe that nothing had changed since 1850. That once admirable zeal has, with the two Joys, become flaccid and cynical with its own success.

The tone of modern manuals implies that mere intercourse is hardly worth bothering with. In fact sexual feeling is now considered to lead in so many equally desirable directions toward so many equally desirable practices that it’s unusual anymore to hear sex spoken of as a desire or need or drive or even an urge. Today we have sexual “preferences,” a word that suggests the refinement and control over our sexual feelings that modern books seem to think necessary. At the same time the zeal that once argued for the personal benefits of sex has gone on unabated. Sex is supposed to wash away all the evil in our souls and bring out all the good. Yet how is this possible for something that is only a preference?

As desires are reduced to preferences and orgasms are elevated to mystic experiences, the gap between what people actually experience in sex and what they hope to experience widens until it is impossible to cross except in fantasy. And that, I think, is how people are crossing it. If there is one single act that defines modern sexuality it is not the freewheeling sex of the two Joys but the activity of the person alone fantasizing about sex, the masturbator. I have already mentioned how much time “J” devoted to the topic. Dr. Reuben, in Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex, lists 37 subheadings under masturbation, but has no listing for love, marriage, emotion, respect, or anything similar. Masturbation is described in many books as a therapeutic measure; women who have trouble reaching climaxes with their lover are advised to use vibrators to bring themselves to orgasm, on the theory that this will make things easier for them. Pornographic movies, skin magazines, the pictures in the two Joys, can all be aids to masturbation; there is a large and steady demand for all of them. And, almost as if to punish us for our isolation, in the two Joys and the newest magazines and movies there is an increasing fascination with and glorification of sadism. The Story of O is only the most obvious example of a trend that can be seen in publications ranging from the sleaziest skin magazines to photographs by Richard Avedon in a recent issue of Vogue. What once sought to arouse by exposing nakedness now seeks to arouse by portraying pain.

We are, I believe, no longer reaching out for the possibilities of sex but in retreat from everything that has presumed to tell us what those possibilities are, or, it seems, were. The assumption used to be that one wouldn’t masturbate if one had the real thing available, but by now so many extreme claims have been made for the real thing—orgasm is the most religious experience of our lives, for example—that many people no longer feel that their own experience has been the real thing at all. No matter who one is with or what is happening, real sex seems always to be some place else with someone else. Bizarre experimentation, group sex, swinging, bisexuality are, at least in part, attempts to bring on, perhaps by novelty, fear, or surprise, the orgasm that fulfills all the glorious promises. But other people are a problem in the search for glory. They will want one to make good on the promise and will see every failure. With someone else the man finds himself impotent and the woman discovers that it wasn’t as good as with her vibrator after all. She retreats home thinking how it would be if she were the perfect lover she’d read about, capable of orgasm after transcendent orgasm, and he retreats home, wishing he knew just one such woman, one who would take him with her out of the world.

- More About:

- Health