THE FIRST TIME PRESIDENT JOHNSON told me that he wasn’t going to run for reelection, I thought he was pulling my leg. It was the late summer of 1967 and we were in his bedroom, where I went every weekday morning to discuss issues prior to starting my press briefing. He instructed me to start working on a withdrawal statement. “You don’t tell anybody; nobody knows but Bird and me,” he said. “I don’t know when, but I think we ought to do it before the first of the year.”

His reasons were based entirely on health. His heart attack in 1955 had almost killed him, and the other shoe would drop sooner or later. The men in his family died young. Disability bothered him more than sudden death; Woodrow Wilson’s stroke had left him barely able to function in the latter part of his presidency, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s health was failing even as he was running for another term. As he talked on, I decided that he was in a blue funk about something and would change his tune by nightfall. I was in no hurry to compose a statement.

A couple of months later he called me in San Antonio, where I had quartered the traveling press while he visited his ranch, and said, “Let’s talk about this withdrawal.” For a time he talked about his health again. But then he brought in other personal problems: his daughters had to be in the limelight, his wife had no freedom from the goldfish bowl; he couldn’t politick while he was trying to find peace in Vietnam. It became clear that he was thinking of anything to justify his decision. He wanted out, but he couldn’t find the right way to get out.

Finally he dispatched me to Austin to see his most trusted adviser, Governor John Connally, whom he had told of his plans. I was to extract from Connally a rationale for the decision to withdraw. At the dining table in the Governor’s Mansion one Saturday afternoon, Connally and I spent two or three uninterrupted hours trying to develop some eloquent and credible prose. Much of the time Connally, who had decided not to run for reelection himself, played Johnson’s surrogate and dictated in a stream of consciousness as if he were making a formal speech.

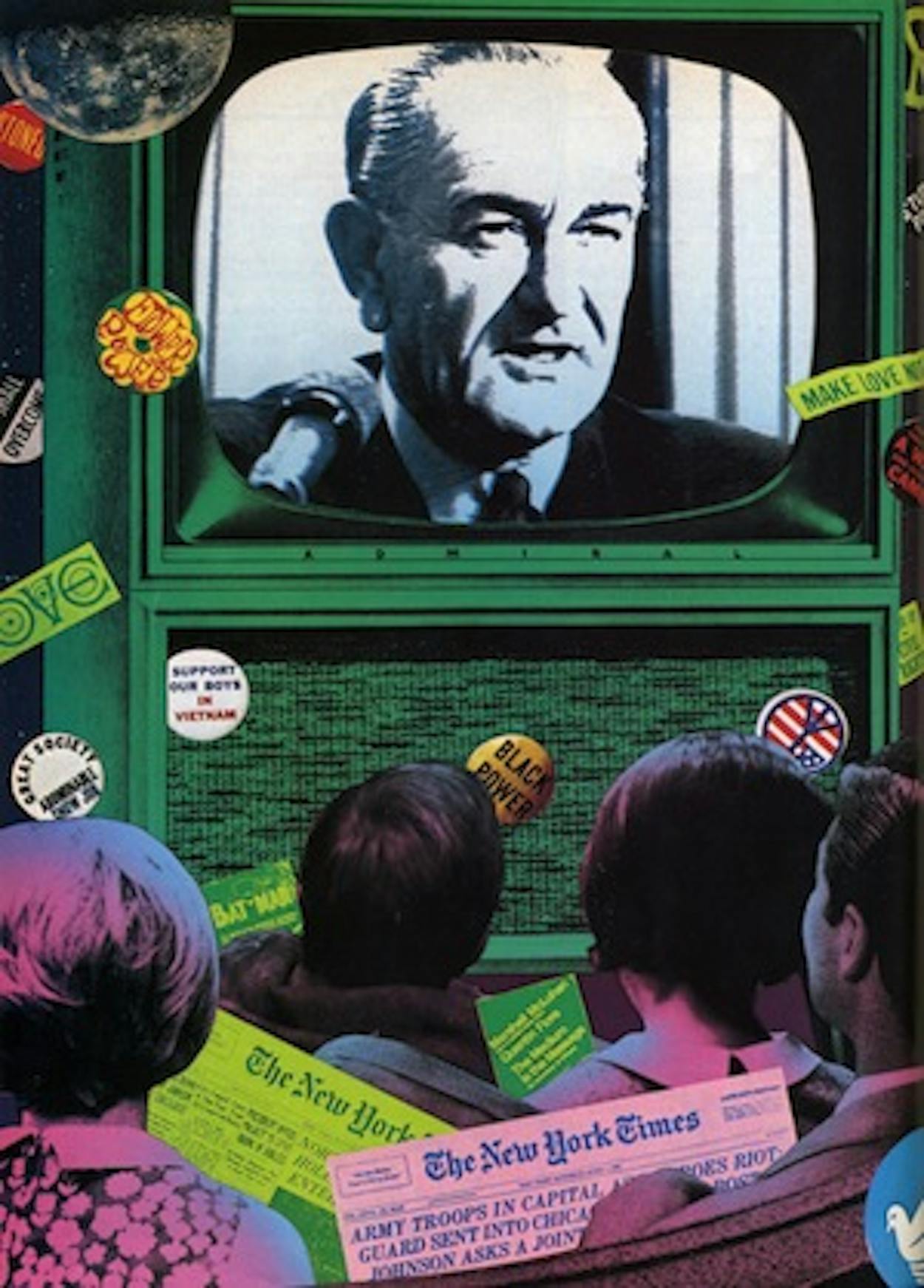

Johnson’s intentions were to announce his withdrawal in December, perhaps at a Democratic party gathering. He abandoned that idea and began shooting for the State of the Union address to Congress in mid-January 1968. By then I couldn’t visualize another term in office. It was becoming more and more difficult for the president to travel because of the peace demonstrations. The cities had been a racial powder keg, and no relief could be foreseen for 1968. How were we going to campaign? Moreover, how was he going to run the country after the election?

I was allowed to confide his intentions to my young assistant, Tom Johnson, but I had no idea if anyone else in the White House was aware of them. Later I learned that he had widened the circle slightly. Just before Christmas the prime minister of Australia, Harold Holt, was lost at sea while taking a swim. The president went to Melbourne for the memorial service, and one of his guests was Horace Busby, a former aide who had helped write his most important speeches. Our trip turned out to be a five-day endurance test to Australia, Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, the Vatican, and back to Washington for Christmas Eve.

Somewhere between Karachi and Rome, Busby told me later, Johnson came out of the presidential cabin and sat down next to him. A news blackout, in force while the president was in Vietnam, had just been lifted, and Johnson was in high spirits. He imitated David Brinkley saying, “We’re sorry to report that the president of the United States has just been found.” Then he looked out the window, where you could see the lights of Tehran, and his mood changed. “The poor shah,” he said. “They have so little time and so little to work with.” After a long silence he said to Busby, “What do you think we ought to do next year?”

Busby said instantly, “Not run.” Johnson fixed his eyes on him, and when Johnson did that, you knew you were being looked at. But Busby had been around him long enough to know not to retreat. Neither man said a word. Johnson held the stare for a long time, then got up without further conversation.

In January, a couple days before the State of the Union address, Johnson summoned Busby to the White House. “I want you to write the closing for my State of the Union,” Johnson said. “When I get through, I’m going to surprise the hell out of them. I’m going to reach back in my pocket and pull out this statement you’re going to write.” He told Busby what he wanted to say: he had persevered, kept the faith, now he was going to leave.

The next day the president gave me Busby’s draft and told me to combine it with the best words Connally and I had been able to devise. On the day he was to go to the Capitol, I gave him four type-written sheets that ended, “I have prayerfully concluded that I will not be a candidate for reelection.”

That evening I stood in the back of the House chamber, waiting for the immortal words. I could hardly contain myself, relishing the surprise and wondering whether Congress was going to applaud or weep. The words never came, of course, and he told me afterward that he thought it was the wrong time to do it. “It just didn’t fit,” he said. “I couldn’t go in there and lay out a big program and then say, ‘Okay, here’s all this work to do, and by the way, so long. I’m leaving.’” He wrote in his memoirs that he had given the closing speech to Mrs. Johnson and had forgotten to get it back, but I’ve always figured he was joshing.

Only a few days later, the U.S.S. Pueblo, an intelligence-gathering ship, was seized by the North Koreans. At the end of January the North Vietnamese launched their Tet offensive. Had Johnson withdrawn before then, these two crises might have been attributed to his decision, and he would have been denounced for leaving the United States weak and leaderless.

After Tet, I thought that the chance to quit was gone. Our people were gearing up for the 1968 campaign, and Johnson was doing nothing to stop them. He refused to allow his name to be put on the ballot in the New Hampshire primary, but he did approve a write-in campaign, which he almost lost to Senator Eugene McCarthy.

History records that Tet was a military reversal for the Communists, but its effect on the U.S. and world opinion was enormous. In February and March there were hard decisions for Johnson to make: whether or not to increase the troop levels in Vietnam, whether or not to believe various reports that the enemy was ready for negotiations, whether or not to limit the bombing. Advisers who had been hawks were turning around and faulting Johnson’s policies.

To add to all of the other problems, Johnson’s old foe, Bobby Kennedy, jumped into the presidential race after New Hampshire. I still believed that Johnson could get the nomination, but not without a bitter fight, and if he won a second full administration, it was destined to be an absolute horror: the war, the riots, the campus turmoil, the increasingly critical press. Johnson himself once said, “I don’t believe I can unite this country.”

In mid-March Harry McPherson, White House lawyer and chief speechwriter, wrote a long memorandum about the pending campaign. “I think the course we seem to be taking now will lead either to Kennedy’s nomination or Nixon’s election or both,” McPherson said. “When you say stick with Vietnam, you’re saying stick with a rough situation that shows signs of getting worse. When you say persevere at home, you’re saying keep the new programs proliferating, although the Negroes rioted last summer and will probably riot again. When you say prepare for austerity, you’re saying to the businessman and taxpayer, get set for a shock, and meanwhile I’m going to continue the programs, particularly Vietnam, that caused the shock.” I think that memorandum had a lot to do with making Johnson realize that he had to fish or cut bait.

On March 30, a Saturday, Johnson called Busby again. “What do you think we ought to do?” he asked. Busby advised him to make up his mind before Tuesday. The Wisconsin primary was set for that day, and all potential candidates were required by state law to be on the ballot. The president was not going to campaign, and it would look bad to quit after a defeat.

Johnson had scheduled a television address for Sunday night, March 31, to announce the curtailment of the bombing in most of North Vietnam as a bid for peace talks. McPherson had written the final draft, and Johnson told Busby he would send it to him. “While the messenger is on the way out, you redo what you did in January and send it back down here,” he said. “Don’t mark ‘eyes only, secret, classified’ on the envelope, because that way twenty-five people will read it before I see it. Just put ‘L.B. Johnson.’” The envelope made it to Johnson unopened, and he handed the contents to me with the statement that “this will be my peroration.”

At last Lyndon Johnson had found the right moment. He had to withdraw while ordering de-escalation of the war. Otherwise the peace bid would not be taken seriously by Hanoi and the world at large. It would be called a political stunt to try to influence the Wisconsin primary. In order to maintain his credibility and validity as president, he had to sacrifice his political career.

Johnson asked Busby to come to the While House early Sunday morning. As Busby told me later, Johnson said, “This thing is closing in on us. I have to think, ‘If I do this, will some general decide that he’ll just go off and have his own little war with China?’” As Johnson was leaving for church, Busby asked, “Mr. President, what do you think the odds are?”

“Seven to three against,” Johnson said.

Busby called me at home and said Johnson was wavering because of pleas from his family and close friends who were houseguests. I said, “Hang in there, Buz. Don’t let him get off the hook.”

Soon Busby called again. “I’ve got to have help,” he said. “They’re going to talk him out of this. This is terrible over here. There are tears, people up and down the hall crying. I can’t hold this fort by myself.” I went down there in a hurry.

Things had settled down a little by the time I got there. One of the houseguests had tears in her eyes, and Luci had obviously been crying. Johnson seemed to be in a calm, quiet state of mind out of our reach.

That afternoon Johnson started dropping hints to his staff. He told Busby not to go near the staff in the West Wing. He was inflaming them by saying, “Buz is over there in the White House, and he thinks I ought to quit.”

The speech was scheduled for 9 o’clock, and at 7:30 the five pages Busby had written as a conclusion still weren’t typed on the TelePrompTer. The first two went on, then the next two, and finally, at 8:15, the last page with the words, “Accordingly, I shall not seek–and will not accept–the nomination of my party for another term as your president.” My deputy press secretary, Bob Fleming, was in charge of proofreading the TelePrompTer, and as he started reading the last page, he literally dropped his pipe right out of his mouth onto the floor. I still wasn’t positive that Johnson would do it, but I was convinced enough to tell the press over the loud-speakers that they might want to listen because there might be an addition to the prepared text.

When I heard the long-awaited words, all I felt was absolute relief. We spent the rest of the night briefing the press, and I just relished telling them the whole background, how long it had been in progress. I felt like saying, “We taught you characters; we actually pulled one off that you didn’t hear about.” It was the first time in history that nothing had leaked.

Johnson was as happy that night as I ever saw him. The burden was off, and he was like a young boy. He had a midnight press conference, trying to portray the whole exercise as rather routine. And you know, 80 percent of what he told them was true.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- LBJ