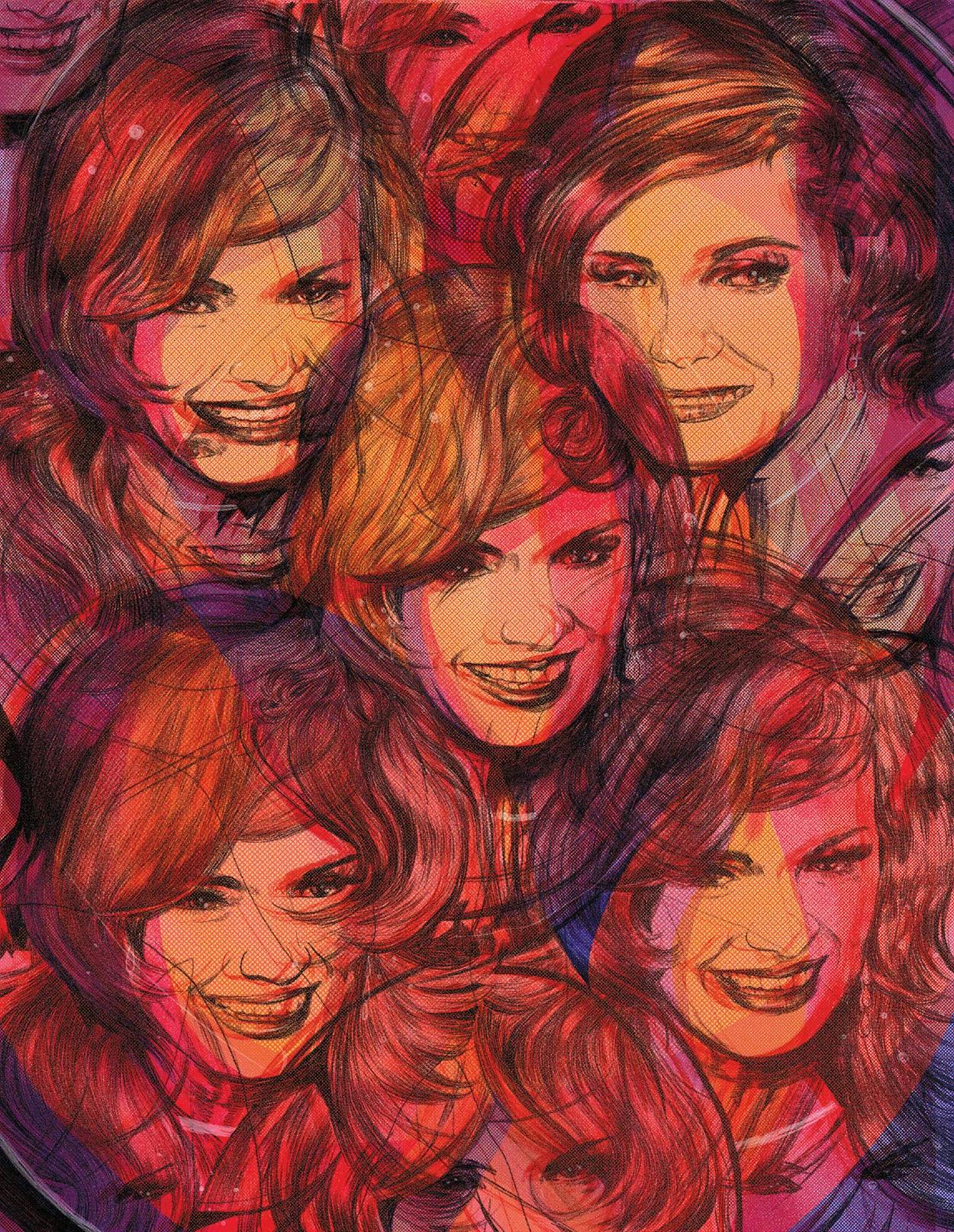

In the mid-sixties, Candace Mossler was one of the most widely known socialites in Houston. She was in her forties, vivacious and full of charm, with wavy blond hair, deep-blue eyes, and a surgically enhanced figure that was often remarked upon in the many newspaper columns written about her. She had an easy smile and a soft, breathy voice.

Her three-story mansion, which was reported to have 28 rooms, was located in River Oaks, the city’s richest neighborhood. There, she threw lavish fundraisers for local charities and arts organizations. Famous musicians such as Chuck Berry would sometimes perform on a stage erected on her back lawn, next to the tennis court and steam-heated swimming pool.

Want True Crime stories like this on your Facebook feed? Like Texas Monthly on Facebook.

Candace always made grand entrances at her soirees, gliding down the circular staircase after everyone had arrived. She liked to wear high-heeled pumps, diamond jewelry, and elegant designer dresses that stopped just above her knees. “Bless your heart, thank you so much for coming,” she’d say while mingling with her guests. She’d tell stories about her six children and her husband Jacques, a wealthy financier who had controlling interests in banks, loan companies, and insurance firms.

Jacques, a slightly paunchy but distinguished-looking man with slicked-back silvery hair, was 25 years older than Candace. He rarely attended his wife’s parties. As one reporter wrote, Jacques preferred “anonymity in the business world.” He often spent time in Miami, where three of his banks were located.

That’s where he was the last week of June 1964. Candace and four of the Mossler children happened to be visiting him that week, staying at his luxury oceanfront apartment on Key Biscayne, a quiet beach community just across a causeway from Miami. The kids enjoyed playing on the beach, as they always did, but Candace said she was not feeling well. She went to a hospital four times to be treated for what she described as nagging migraine headaches.

On the last of those trips, which took place in the early morning hours of June 30, she brought along her children. She stopped at a hotel to mail some letters and then took the kids to a diner for hamburgers. At the hospital, she received an injection to ease the headache, and at roughly 4:30 a.m., she and the children returned to the apartment.

When they walked inside, Jacques was lying on the living room floor, wrapped in a blanket. He had been bludgeoned over the head with a blunt object and stabbed 39 times in and around the heart and lungs with a long-bladed knife.

The murder was front-page news in both Miami and Houston. “Houston Millionaire Stabbed to Death” was the headline in the Houston Chronicle. “Millionaire Banker Slain on Key Biscayne,” trumpeted the Miami News. Because Candace claimed that Jacques’s wallet had been emptied and that several hundred-dollar bills were missing from the bathroom counter, along with her gold-and-diamond wristwatch, detectives from the Dade County Sheriff’s Department initially speculated that Jacques had been killed by a burglar.

But Candace also suggested to them that her husband had made plenty of enemies over the years, from rival bankers to disgruntled ex-employees and resentful customers who’d had vehicles or appliances repossessed by his companies. What’s more, she revealed, she’d been told that during his trips to Florida, Jacques sometimes invited young men he’d met on the beach to his apartment. Candace said that during the week she and the children had spent on Key Biscayne, her husband had received phone calls from a man who spoke in “feminine tones.” Candace told detectives she suspected Jacques had been living a closeted life and that he’d been murdered by one of his lovers.

Within days, however, detectives discovered that Candace had been leading a clandestine life of her own. For nearly two years, she’d been carrying on an affair with her nephew, a 22-year-old mobile home salesman named Melvin Powers. Mel was six foot four and built like a linebacker. He had high cheekbones, dark eyes, and a head of coal-black hair. He and Candace had written each other impassioned love letters. They’d had trysts at the mansion, the family’s ranch just southwest of Houston, and the Mosslers’ Galveston beach house.

And at some point, the detectives concluded, Candace and Mel had devised a plan to do away with Jacques so they could get hold of his multimillion-dollar fortune. “It was like a great trashy novel had come to life,” Betsy Parish, a former society columnist for the Houston Post, told me. “Candace was beautiful. She lived in this great mansion. She gave away money to worthy causes. She had all these children she adored. She had everything she could possibly want. And then the police announced that she and her lover-boy nephew were cold-blooded killers. You could have knocked River Oaks over with a feather.”

I’d called Parish in 2017 after reading a couple of old newspaper articles about the murder. After spending decades covering Texas’s biggest crime sagas, I thought I’d heard all the stories, but Candace had somehow escaped my notice. I confessed to Parish I knew next to nothing about Candace’s life or her murder trial, which the New York Times described as “one of the most spectacular” courtroom dramas in history.

“Honey, you missed out,” cackled Parish. “For a while, Candace was the most famous woman in America. Everyone was talking about her. And have you heard the rumors about what happened to her next husband?”

“What happened?” I asked.

Parish cackled again. “You ought to look into it before everyone who knew her dies off. [Parish died less than a year after I spoke with her.] I still don’t think the full story about her has ever been told.”

I began doing some research: poring over more than a hundred old newspaper and magazine stories, obtaining police and court records, and reaching out to Candace’s relatives and other Houstonians who had known her. This past January, I paid a visit to 88-year-old Mickey Herskowitz, a former Houston sportswriter who’d moonlighted as a ghostwriter for the likes of Gene Autry, George W. Bush, Bette Davis, Mickey Mantle, and Dan Rather. I learned that in the early seventies, Herskowitz had interviewed Candace a few times for a biography of her she wanted him to do. Although the book was never published—Candace’s lawyers and family members persuaded her to scrap the project, telling her she didn’t need any more publicity—Herskowitz still had part of his typed manuscript, yellowed with age, which he dug out of his garage and handed to me.

“I have to admit, I used to stay up at night thinking about her, wondering what she did or did not do,” Herskowitz said.

“Maybe you can figure her out, but I don’t know,” Herskowitz said as we sat in his living room. “She’d stare at me with those blue eyes and tell me in her little-girl voice that she did her best to live a good life. She’d tell me she was not a hateful woman. She’d say that she would never resort to violence. And she always gave me a long hug when I left and would tell me to come back soon.”

Herskowitz, who suffers from a bad hip, slowly leaned back onto his couch. “I have to admit, I used to stay up at night thinking about her, wondering what she did or did not do to her husbands,” he said.

Herskowitz wasn’t the only writer flummoxed by Candace. It seemed that every reporter who interviewed her found her delightful, with one gushing over her “ceaseless effervescence” and another entranced by her “great beauty and charm.” Of course, in a manner common to journalists of her day, there was plenty more ink devoted to her looks. She was described as “shapely,” “lissome,” and “stylishly coiffed,” filled with “dash and flair.” Even the straitlaced Joyce Brothers, a celebrity therapist Time magazine once called “the gadabout lady psychologist,” was smitten. After interviewing Candace for her nationally syndicated newspaper column, Brothers characterized her as having “an appealing little-girl-lost quality.”

“Seriously, it was hard for anyone who met Candace to imagine that she could kill anything, even a flea,” Herskowitz told me. “She was so kind, so pleasant, so damn friendly.”

He shifted again on the couch. “To be honest, she haunts me to this day.”

Candace didn’t exactly grow up with a silver spoon in her mouth. The sixth of twelve children, she was born in 1920 in the town of Buchanan, Georgia, about 55 miles west of Atlanta. Her father, Lon Weatherby, was a farmer. Candace’s mother, Lizzie, spent much of her adult life pregnant.

The family had no telephone or radio. All of the kids stayed busy with chores: planting crops, picking cotton, and collecting eggs from the chicken coops. In his manuscript, Herskowitz described it as “hardscrabble living, when the South was still 40 years behind the luxuries of the North.”

Candace was an adorable girl with a halo of blond hair. She was also theatrical. One of her nieces told me that Candace loved playing make-believe. “My favorite story I heard about Aunt Candace was that she wore her nightgowns everywhere, even to church,” the niece said. “When someone asked her why she was wearing a gown, she’d say that she liked pretending that she was a princess.”

When Candace was twelve, her mother died while delivering her thirteenth child, who was stillborn. According to family lore, Candace’s father turned to corn liquor to deal with his grief. He suffered a breakdown and moved out of Buchanan, leaving the younger children with relatives. Candace essentially raised herself.

When she got to high school, her grandfather encouraged her to start looking for a husband—a stable man she could count on to care for her. She was introduced to Norman Johnson, a family friend and civil engineer ten years her senior who lived in Anniston, Alabama, fifty miles west of Buchanan. They married in 1939, when Candace was nineteen, and settled in Anniston. A year later, Candace gave birth to a son, Norman Jr.

But Candace wasn’t content being a homemaker in small-town Alabama. To get out of the house, she began volunteering with the United Service Organizations, the military-support group. She and other young women helped host parties for soldiers at Fort Benning, Georgia, about 120 miles south of Anniston. At one of those parties, she met an Army officer named Winthrop Rockefeller, a son of the New York industrialist John D. Rockefeller.

Before Rockefeller was shipped overseas to fight in World War II, he and Candace became close—according to some accounts, very close. In fact, years later, during a court hearing in Houston regarding the disposition of the Mossler estate, an attorney asked Candace why she gave her second child, Rita, who was born in 1943, the middle name Rockefeller. “Was she the daughter of Winthrop Rockefeller?” the attorney asked. Candace’s lawyer refused to let her answer the question.

It’s not clear that Norman ever learned of Candance’s relationship with Rockefeller. In the mid-forties, he moved her and the two children to New Orleans, where he’d landed an engineering job at a shipyard. But their marriage soon fell apart. Norman moved west, eventually settling in Boulder, Colorado, and she stayed in New Orleans with the children.

Candace set about launching her own career. She decided she was going to be a fashion model. She quickly found gigs modeling clothes for local department stores and also designed lingerie. At one point, she dropped off the kids with one of her sisters, took a train to New York City, and attended classes at the Barbizon School of Modeling.

When she returned, she opened the Candace Modeling and Self-Improvement School (the name changed multiple times over the years) on Peniston Street, near the city’s fabled Garden District. She placed ads in the Times-Picayune promising to advise young ladies on makeup and hairstyling, provide tips on maintaining “a streamlined figure,” prepare them to model in fashion shows, and imbue them with “self-confidence, grace, poise and elegance of speech that will make you a person of real distinction.” The ads usually included a photo of Candace, a smile lingering about her lips.

Incredibly, the poor little Georgia farm girl had transformed herself into a big-city entrepreneur. To attract clients, she hosted free seminars on such topics as how to properly wear women’s hats. One Easter Sunday, reported a local paper, she threw a “fashion parade,” leading 45 of her modeling students up and down Canal Street, accompanied by numerous high school marching bands.

While researching his book, Herskowitz picked up an intriguing rumor that Candace had other ways of earning money in New Orleans: She occasionally worked as an escort. She was also said to have run an entire outfit of sex workers. Young soldiers back from the war would come to her house and sign up for dance classes. Each was paired with a female partner. They’d dance for a while before retiring to one of the bedrooms, and the soldier could use his GI Bill benefits to pay for his “lesson.”

Apparently these rumors didn’t hold Candace back. She decided to get involved in the city’s arts scene, applying for a volunteer position with the New Orleans Opera. She told the organization’s executives that she would be more than happy to meet with prominent businessmen and solicit donations. The executives gladly took her on. And one of the men they suggested she target was a New Orleans banker named Jacques Mossler.

Jacques was a native of Romania. As a boy, he had emigrated with his family to Buffalo, New York, and eventually made his way to New Orleans, where he opened a used car dealership. In those years, he was known to cut corners to turn a profit. In 1916 the Times-Picayune reported that the 21-year-old Jacques had been arrested for grand larceny after a doctor’s car was stolen from a hospital and later found in a garage at Jacques’s dealership. (I couldn’t find any records indicating whether he was convicted.)

Jacques’s brothers ran the business while he served in the Army during World War I. After he returned home, he sold his dealership and began opening small loan companies, offering customers without much credit history or collateral the opportunity to buy automobiles, appliances, and furniture at high interest rates. He sold home mortgages. He invested in insurance firms and banks.

By the time the 27-year-old Candace walked into his office in early 1947, Jacques was 52 and regarded as wealthy. Like Candace, he was also recently divorced: he had left his wife of 30 years, with whom he had four daughters. He wrote a check to the opera for only $25, telling Candace that opera bored him. But he was definitely not bored by Candace. Weeks later, she and her children were at the Audubon Zoo, and they just so happened to pass right by Jacques, who was known to stroll there on his lunch breaks. In May 1949, while on a trip to Fort Lauderdale, Jacques and Candace got married at a Presbyterian church.

When they returned to New Orleans, they began packing their belongings. Jacques had decided to establish a new headquarters for his burgeoning business empire in a city neither of them knew well: Houston.

In 1950, Houston was awash in money. The city “uses dollars as Niagara Falls uses water,” wrote George Fuermann, a newspaper columnist who that year was finishing a book titled Houston: Land of the Big Rich. Oilmen made deals on downtown street corners. One particularly flamboyant member of that fraternity, Jim “Silver Dollar” West, tossed silver dollars out of the window of his Cadillac to passersby. Another local businessman, attempting to motivate his daughter to lose weight, offered her $5,000—the equivalent of $57,000 today—for every pound she dropped.

At night, the city’s elite often gathered at the Shamrock Hotel, which the wildcatter Glenn McCarthy had opened on St. Patrick’s Day the previous year. (For the Shamrock’s opening celebration, McCarthy flew in Kirk Douglas, Ginger Rogers, Errol Flynn, and Lana Turner, star of The Postman Always Rings Twice, the 1946 film noir about a bored housewife who has an affair with a drifter and convinces him to murder her much-older husband.) I came across a photo of Jacques and Candace having dinner at what looked to be the Cork Club, the Shamrock’s most-exclusive restaurant. Two violinists had paused to play at their table. Jacques, in a dark suit, was holding a glass of red wine. Candace was wearing a white fur wrap over a dark dress, and her hair was pulled back into a chignon. Etched across her face was a look of pure delight.

On a three-acre plot of land on Willowick Drive, in River Oaks, Jacques built Candace a castle: a three-story redbrick mansion staffed with maids, cooks, butlers, gardeners, handymen, and a chauffeur. Candace’s personal maid was an Egyptian woman who spoke three languages. Adjoining the house was a seven-car garage filled with luxury automobiles.

Candace quickly began making her way up Houston’s social ladder. She wrote check after check: to the Alley Theatre one day, to heart disease research the next. She threw fundraisers at the mansion, and many attendees came out just to get a glimpse of Candace. She strolled from room to room in stilettos, greeting her guests with a kiss on the cheek.

“None of us knew anything about her,” said Joan Schnitzer, a longtime Houston socialite and philanthropist who attended a couple of Candace’s parties in those years with her husband. “But far as we could tell, she didn’t have a mean bone in her body. She was fun and flirty. All she had to do was touch an older gentleman on the arm and say, ‘I really love your tie,’ and you could just see him melt.”

Inevitably, the rumors about Candace’s secret life in New Orleans made their way to Houston. Joanne Herring, another grande dame of the city’s contemporary social scene, told me she first heard the murmurings at a dinner that Candace was throwing to benefit the Houston Opera. “One of my friends took me off to a corner and whispered, ‘Have you heard that Candace was a call girl in the French Quarter?’ I said, ‘Oh my God! I knew there was something different about that woman.’ ”

Of course, even if the rumors were true, Candace certainly wouldn’t have been the first woman in Houston with a past to marry a wealthy older man. What’s more, it was hard for the city’s social crowd to condemn someone whose philanthropy often went above and beyond. She volunteered at multiple hospitals. She took a special interest in the Houston Boys Club, donating $15,000 to build bathhouses for the kids at the youth center’s pool. In January 1957, Jacques called her from a business trip in Chicago to tell her he’d just read about four local siblings, ages two through six, who’d been left homeless after their father shot their mother and stabbed their baby brother to death. Candace soon boarded a flight to the city, and she and Jacques signed custody papers for all four children (the adoption would become final later).

The story was picked up by the wire services and printed in newspapers from coast to coast. (“Day of Tragedy for Children Gives Way to Fairy Tale Life,” went one headline.) When Candace walked off the plane at Houston International Airport with Jacques and their new brood—Martha, Daniel, Christopher, and Edward—photographers were waiting. Candace, as ever, was camera-ready, wearing a black dress with black pumps.

She became one of the most famous women in town and a favorite subject of journalists. She served as team captain for the United Fund campaign; as chair of the prestigious Pin Oak horse show, which raised money for the Texas Children’s Hospital; and as general chair of the fund drive for the Houston Opera.

Candace was also an active member of the First Presbyterian Church, always arriving for Sunday morning services “dressed to the nines, like she had come straight from a party,” Parish, the Post’s former society columnist, told me. Most weeks she brought along her adopted children and put them in Sunday school.

Indeed, there was no mother in River Oaks quite like Candace. She turned the mansion’s ballroom into a giant playroom. She had her chauffeur take the children to drive-in movies, to a bowling alley, to the family’s ranch, and to their Galveston beach house. She and Jacques arranged for a baseball field to be built on a lot across from their home, and one of Jacques’s employees taught the children to play sports. Once, Candace even had a chimpanzee named Jock-O brought to the mansion to play with the kids.

“They’re my life—my entire world,” Candace told the reporters who came to see her. “People can work hard and accomplish a lot of things, but it is useless without children to love.”

As the fifties came to a close, Candace seemed to have it all. Then, in late 1961, Candace got a phone call from Elizabeth “Babe” Powers, her older sister. Babe said she needed help. Her twenty-year-old son, Mel, had been thrown in jail.

Raised in Alabama and Arizona, where his father operated a small commercial aviation service, Mel had been an aimless boy, expelled from school for excessive absenteeism. He later got a job going door to door selling magazine subscriptions. During a work trip to Michigan, he persuaded an 89-year-old man to buy $20,000 of worthless stock in a fake magazine-subscription firm. Mel was convicted of fraud and sent to jail for ninety days.

That’s what had spurred Babe’s phone call. She asked Candace if Mel could come to Houston after serving his jail sentence and stay at the Mossler mansion until he found a job and got back on his feet.

Of course, Candace said.

When Mel showed up, he must have made an impression. Although his face was pockmarked by acne scars, he was muscular and movie-star handsome. Candace gave him his own bedroom and a Thunderbird to drive. Mel also underwent four operations, presumably at the behest of Candace. He was circumcised, his tonsils were removed, his ears were cosmetically adjusted to lie flatter against his head, and his face was sanded.

Jacques agreed to give Mel a job as a “repossessor” at one of his loan companies. Mel turned out to be a fine employee who “had the easy repartee of a salesman,” one reporter would later write.

But in June 1963, about a year and a half after Mel’s arrival, word began to spread through River Oaks that something was going on at the Mossler mansion. According to the gossip, Jacques had fired Mel, hired security guards to escort him off the estate, and had forbidden his return. Jacques had then left Houston for his luxury apartment on Key Biscayne.

Candace told anyone who asked that Jacques kicked Mel out of the mansion because Mel had announced that he was planning to leave his job in order to start his own business. And Jacques was in Florida, she added, to oversee the opening of another Miami-area bank. She and Jacques were getting along just fine, she said. In fact, she and some of the Mossler children would be visiting Jacques soon.

They arrived in June 1964, after school let out. Although Candace seemed to be having a good time hanging out with the kids on the beach during the day, she began making trips to the hospital at night, always bringing along the children, so she could receive shots to ease those nagging migraines.

The children would later tell police that they weren’t bothered by their mother’s excursions. She was a night owl, they said. They liked piling into her red Pontiac convertible and going on rides. It wasn’t until they returned to the apartment on June 30 and heard their mother’s gasps that they realized something was terribly wrong.

As the heiress to Jacques’s fortune, Candace was estimated to be worth at least $7 million (roughly $60 million today), and possibly much more. At Jacques’s funeral, in Miami, she sat in the front row, surrounded by her children, and quietly wept. Afterward, she and the kids flew to Washington, D.C., where Jacques was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

Meanwhile, detectives from the Dade County Sheriff’s Department were following the three leads Candace had supplied—that a burglar or a business rival or perhaps a lover might have killed Jacques. The detectives sensed they had a top-drawer murder mystery on their hands. And the mystery only got more intriguing when someone told them that Jacques had actually booted Mel out of the mansion after a member of the household staff had spotted Mel and Candace canoodling.

The detectives discovered that on the afternoon of June 29, Mel had arrived at the Houston airport and purchased a one-way ticket to Miami. A flight attendant said Mel was carrying a briefcase as his only luggage. After he arrived in Miami, he was seen at the Stuft Shirt Lounge at a Holiday Inn not far from Jacques’s apartment. He went to the bar several times. On his first visit, he asked for an empty glass soda bottle and left with it in his hand. When he returned around 1 a.m., closing time, he ordered a double scotch. By the time Candace called the police to report the murder, Mel was back at the Miami airport, purchasing a one-way ticket to Houston.

Since Mel’s eviction from the Mossler mansion, he had been living in an apartment and operating a small mobile-home sales business south of the city, not far from the new Manned Spacecraft Center. The detectives flew to Houston to interview him. He swore he had been in Houston the night of Jacques’s murder. He had gone to see a movie, he said, though he couldn’t recall the name of the film or the theater where he’d seen it. He was arrested and charged with capital murder.

While searching Mel’s office, the detectives found a photo of Mel and Candace sitting close together at a nightclub, and they came across a couple of letters that Candace had written Mel during stretches when she’d been out of town. “My darling,” one of her letters began, “the image of your face is before me . . . I can almost feel your face against mine . . . I could not think of life without you . . . I love you. I need you. I long for you.”

Soon the newspapers were reporting that the detectives were looking into the possibility that Candace was involved in the killing. “I was speechless, and I’m not often at a loss for words,” said Lynn Sakowitz Wyatt, the octogenarian Houston department store heiress, who is now one of the world’s most celebrated socialites, known for the soirees at her River Oaks mansion and at her home in the south of France. “I remember that people came from all over just to drive past her home, hoping to get a look at her. There were literally policemen in front of her house directing traffic!”

But Candace wasn’t at the mansion. She had sequestered herself inside St. Luke’s Hospital, where she claimed to be suffering from what her doctor described as “nervous strain.” Standing sentry outside her room were two private security guards. Candace did let newspaper reporters gather around her bed for an impromptu press conference. She was wearing a pink nightgown. Her blue eyes were swollen from crying. “Oh, poo!” she exclaimed when a reporter asked whether she thought Mel had murdered her husband. “That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard. If an atomic bomb were to fall, Mel would have been the first one to drag Jacques and the children out of the wreckage.”

She called the idea that she and Mel were having an affair “absurd.” They had been with a group of friends at a nightclub when the photo was taken, she said. And the letters she had written? Candace explained that was the way she wrote to everyone among “my family and my close friends.”

A reporter then asked if she was worried that she too might be arrested. Candace tossed a hand over her mouth and said, her voice trembling, “How can something like this happen in this country? I don’t know how they can do this. I guess some people could cast reflections on Jesus Christ Himself.”

For the next year, while the detectives worked the case, Candace spent much of her time with her children and their governess in Rochester, Minnesota, where she rented adjoining apartments and made appointments at the Mayo Clinic to treat her migraines. She stayed mostly quiet, giving only one interview, to a Miami Herald investigative reporter named Gene Miller, telling him that Jacques had become “unstable” in the last months of his life and that he had been receiving love letters on pink stationery from a man who had also tried to blackmail him for $75,000.

Candace insisted she had deeply loved Jacques and didn’t care about his money. “I would’ve been happy with him in a telephone booth,” she told Miller. In June 1965, she traveled with her children to Arlington National Cemetery to commemorate the first anniversary of Jacques’s death. They knelt by Jacques’s grave and placed roses beside his tombstone. A professional photographer hired by Candace took pictures that were sent to the wire services, along with a typed statement detailing Candace’s various medical maladies. The statement claimed that doctors had advised Candace not to travel but that she was intent on being at her husband’s grave to signal to the world that “Jacques Mossler is never forgotten.”

At that point, it appeared that the police investigation had stalled. But less than a month after Candace’s visit to Jacques’s grave, a Dade County grand jury indicted her and Mel—who remained in jail in Houston—on capital murder charges. Prosecutors announced that they had uncovered new evidence proving Candace and her nephew had been plotting to kill Jacques for at least a couple of years.

By the time the trial began in Miami, in January 1966, more than forty news organizations had requested seats in the courtroom. Reporters arrived from the country’s most popular magazines: Time, Life, Look, Newsweek, and the Saturday Evening Post. Jim Bishop, whose syndicated column appeared in two hundred newspapers, showed up to cover the trial, as did the Chicago Tribune’s veteran crime writer Paul Holmes.

And of course the New York Daily News’ Theo Wilson, one of the few female journalists in America assigned to the crime beat, was there. Her editors were so convinced Candace would sell papers that they had a thousand posters plastered on the walls of subway stations and on the sides of the newspaper’s delivery trucks that read, “Candy Mossler Murder Trial. Follow Theo Wilson Every Day.”

It was, in short, the O. J. Simpson trial of its era. Rarely had circumstances converged to produce such a sensational story, one that, as the Houston Chronicle put it, was teeming with “love, heat, greed, savage passion, intrigue, incest and perversion.” The Tribune’s Holmes went so far as to say that the trial was “lubricated by sex, nourished by sex and varnished with sex.” And Lewis Lapham, then a 31-year-old staff writer for the Saturday Evening Post, informed his readers that the story was “entertainment as good or better than Peyton Place”—the wildly popular ABC prime-time television drama starring Mia Farrow and Ryan O’Neal—“without any of the chickenhearted editing.”

When I recently called Lapham, now 86, he told me the trial “was unlike anything else I’ve covered, a pure spectacle, comedy and tragedy intertwined, with a leading lady who seemed too good—or maybe too bad—to be true. My editor told me to write as long as I wanted. He said no one was going to be able to turn away from this.”

On the opening day of testimony, Candace arrived at the courthouse dressed in a white trench coat, a white silk sheath dress, and white pumps. As she stepped out of a car, photographers rushed toward her, flashbulbs popping, and reporters shouted questions. “You would have thought she was a movie star walking the red carpet,” said Houston attorney Marian Rosen, who at 31 was the youngest member of Candace and Mel’s defense team.

Accompanied by Rosen, Candace took an elevator to the sixth floor, where a long line of Miamians waited in the hallway behind velvet ropes, hoping to snag a seat in the courtroom. The crowd was mostly women, many of whom, in the words of one reporter, were “rushing downtown after getting the kids off to school.” They gasped as Candace walked past them. She smiled and blew a few kisses to the audience.

Foreman told the jury that “thousands” of people hated the banker. Jacques was “as ruthless in business as any pirate who ever sailed the seven seas,” he declared.

When she entered the courtroom, she sat on the far left side of the defense counsel’s table; Mel had already taken his place on the far right. The couple didn’t exchange so much as a glance. Mel mostly stared at the floor. One reporter observed that Mel was “so big and quiet that he could play Lennie in Of Mice and Men.”

The lead prosecutor, Dade County state’s attorney Richard Gerstein, was a tall, balding former World War II Air Force navigator who had lost his right eye after he was hit by flak during a bombing run over Germany. Miami politicos said he was determined to use the trial as a launchpad for his political career—he had ambitions to run for governor. With his wife watching from the first row—she had bought a new hat to wear to the trial—he told the jury that Candace had seduced Mel, made him believe she was in love with him, and then persuaded him to fly to Miami and murder her husband, whom she no longer loved, while she and the children were conveniently at the hospital, giving Candace the perfect alibi.

Yes, Gerstein said, staring coldly at Candace: Mel did the dirty work, bludgeoning Jacques and stabbing him 39 times, but he was motivated “by his insatiable desire for this woman.”

Then the lead attorney for Candace and Mel, Percy Foreman, rose from his chair. A large man with slicked-back hair and a ruby ring on his left hand, the 63-year-old Foreman was the most famous and flamboyant criminal defense lawyer in Houston. In the courtroom, he was a magnificent orator, renowned for his opening and closing arguments, his gravelly voice lowering dramatically, then rising as he quoted Greek poets, Roman philosophers, Shakespeare, the Bible, and cracker-barrel proverbs.

Foreman liked to boast that he had won acquittals for at least three hundred accused murderers, many of whom had clear evidence stacked against them. In one of his most famous cases, he represented a Houston man who had shot to death his stepdaughter’s teenage boyfriend in front of multiple witnesses. Foreman hauled a church pulpit into the courtroom and delivered a homily on adolescent vice, emotionally reciting a Sir Walter Scott poem about “pious fathers.” The man was acquitted.

Foreman’s usual strategy was to put the victim on trial, which was exactly what he did with Jacques. Standing in the center of the courtroom, he hooked his thumbs into the straps of his vest and told the jury that “thousands” of people hated the banker. Jacques was “as ruthless in business as any pirate who ever sailed the seven seas,” Foreman declared, “a man who received so many threats against his life that he kept an ax beside his bed and frequently summoned thugs and gangsters to his home, employing them to deal with blackmailers.”

Foreman offered no proof to back up any of his allegations. Nor did he have any evidence when he claimed that Jacques was consumed with sexual fetishes—“every conceivable sex deviation that anybody has ever had.” Most notably, Foreman said, Jacques had “an insatiable sex appetite” for high school boys and college students he met in bars “frequented by the gay people.” Foreman roared that “if each of the thirty-nine wounds on the body of the deceased had been inflicted by a separate person—that is, thirty-nine different people—there still would be three times as many people in the state of Florida with enough reason to want the death of Jacques Mossler.”

The all-male jury included a marine specimen collector at the Miami Seaquarium, a bus driver, a mail carrier, a bellhop, a former proprietor of a rooming house, a piano player, and a man one of the Houston newspapers described as “a truck driver of the Jewish faith.” When Foreman sat down, the jurors studied Candace as she blinked back tears and accepted tissues from Rosen, who sat beside her. Candace softly fingered a gold necklace, a long-ago gift from Jacques. “The jurors couldn’t take their eyes off her,” recalled Rosen, who’s now 87 and still practices law in Houston. “There were some courtroom observers who later said they believed the trial was over the moment Candace took a seat in the courtroom and crossed her legs.”

The press corps was certainly taken with her. She chatted with reporters during breaks, and she met with a few of them at night. Holmes, who was invited to have a drink with Candace, wrote that she possessed “a bouncy, unquenchable optimism” and “a flashing smile that lighted up her mobile features.” Columnist Bishop, who sat down for a steak dinner with Candace, admitted to his readers that as he watched her picking at her filet mignon, he found himself wishing her good luck. Candace smiled, rose, gave him a curtsy, and said, “Thank you, sir. The people of Dade County aren’t going to be unjust to me. You’ll see.”

And when Wilson, of the Daily News, dropped by the apartment where Candace was staying, Candace sat on the floor to play with her infant grandchild, born the previous year to Candace’s eldest daughter, Rita. Candace also introduced Wilson to her four adopted children, whom she’d brought to Miami for the duration of the trial and enrolled in local schools under assumed names.

Their ages now ranged from eleven to fifteen. Only nine years earlier, they had watched, terrified, as their birth father in Chicago had murdered their birth mother and their baby brother. And now here they were, having to deal with the possibility that their adoptive mother might be going to prison, maybe even to the electric chair, for murdering their adoptive father.

As Candace looked on, they politely told the writer that their mother was a loving woman who would never have wanted any harm done to Jacques. Candace called over her son Dan, kissed him, and asked him to talk about Jacques. Dan launched into a story about Jacques flashing hundred-dollar bills, even just to buy hamburgers at the Royal Castle, in Miami. He recalled that Jacques would also proposition men he didn’t know, telling them he owned banks and inviting them back to the Key Biscayne apartment. Dan added that he felt nervous when his father would pick up strangers while driving down the highway.

A Miami Herald reporter asked one observer why it was so important for her to be at the trial. “Where else could you find so much human nature?” she replied.

Jacques’s sexuality was a constant theme in Foreman’s defense. He insinuated that Jacques had a relationship with a male vice president of one of his companies. He called to the stand a former handyman of the Mosslers’ who testified that he had seen the banker with three shirtless young men in a trailer at the Mosslers’ Galveston beach property. Jacques and the other men were drinking from a bottle of liquor, the man said. They “talked real loud, kind of fancy.”

Gerstein and his assistant prosecutors fired right back, characterizing Candace as a dangerous adulterer capable of seducing and destroying anyone who dared to get involved with her. The prosecutors called a string of witnesses who described Candace’s own sexual desires as depraved. Some testified that they’d watched Candace embrace Mel while the two were parked in Candace’s Lincoln Continental; one woman said she saw them doing the same in Mel’s Thunderbird. “They were in each other’s arms,” the woman solemnly stated. “They were too passionate for relatives.” A man testified that he saw Candace drive to Mel’s trailer sales lot and begin “a-huggin’ and a-kissin’ ” him. The foreman of the Mosslers’ ranch recounted that Candace and Mel once showed up there, disappeared inside one of the ranch’s trailers, and “rumpled up” the bed.

And one of Mel’s coworkers at the trailer lot testified that Mel often bragged that he could get whatever he wanted from Candace by performing oral sex on her. There were a few seconds of stunned silence as everyone in the courtroom turned to look at Candace and Mel. According to the reporters, Candace “kept a stony face,” while Mel smiled sheepishly. Judge George Schulz was so discomfited by the testimony that he ordered the bailiffs to clear the courtroom of anyone under the age of 21—“a ruling that vastly disappointed a number of teen-aged girls wearing elaborate bouffant hairdos,” wrote Lapham.

There were plenty of women happy to take the teenagers’ seats. Some had arrived at the courthouse as early as five in the morning to wait in line behind the velvet ropes. When the doors opened, they bolted for the wooden benches, ignoring the bailiffs’ pleas to slow down. They carried sack lunches, which they ate during lunch breaks so they wouldn’t have to give up their seats. A Miami Herald reporter asked one observer why it was so important for her to be at the trial. “Where else could you find so much human nature?” she replied.

As the trial went on, it became clear that Gerstein had no direct evidence connecting Candace and Mel to Jacques’s death: no murder weapon (the bottle Mel had taken from the Holiday Inn bar was never found) or eyewitnesses. A fingerprint expert did testify that Mel’s palm print was identified on the kitchen counter in Jacques’s apartment, but there was no way to say for certain when Mel had left the print.

Yet Gerstein still had another card to play. He said that Dade County sheriff’s detectives had interviewed at least five men who claimed that Candace and Mel had tried to hire them to kill Jacques. One worked at the gas station where Mel had his car serviced. He testified that Mel asked him to murder Jacques, drive his body to Mexico, and dump it into a volcano. Another man, the coworker at Mel’s trailer sales office, testified that when Mel tried to convince him to do the job, Mel had taken a letter opener and made stabbing motions over and over, demonstrating how he would like Jacques to meet his demise. The coworker told Mel he wasn’t interested.

And then there was Billy Frank Mulvey, a self-acknowledged thief and “dope addict,” who testified he got a call from Candace asking him to meet her at a Houston beer joint called the 24 Hour Club. According to Mulvey’s testimony, Candace said she’d heard about him when she had served a term on the Harris County grand jury. Mulvey said he told Candace he’d kill Jacques for $25,000—his plan was to rig dynamite to Jacques’s car—but he was arrested and thrown into the Harris County jail on another charge before he got around to it. In July 1964, he continued, he was still in jail when Mel was arrested for Jacques’s murder. They briefly shared a cell, and Mel confessed to him that he had done the killing.

At one point while Mulvey was telling this story, Candace rose halfway out of her chair and cried out, “I have never seen or heard of this man in my life!” Most of the reporters weren’t buying his story either. In fact, they were skeptical of all the alleged hit men, describing them as “shameless and outright rascals,” “nitwits” who had willingly committed perjury in hopes of getting a reduced prison sentence or, at the least, a free trip to Florida, where they could sunbathe on the beach before coming to court to testify.

On March 3, both sides rested and closing arguments began. During his 62-minute summation, Gerstein lit into Candace again, calling her “the mastermind and manipulator of this entire scheme.” He said Candace realized that the only way she could wrest control of the fortune from Jacques was to “eliminate him from the face of the earth.”

But Gerstein couldn’t compete with Foreman’s oratorical brilliance. The defense attorney began his final argument by saying, “I will now make a few brief remarks.” He proceeded to speak for five hours, with three intermissions. He quoted Shakespeare, Wordsworth, H. G. Wells, Buddha, and Jesus. He referred to Mel as “that innocent boy” and to Candace as “that sweet little woman.”

And in a surprise move, he went after the Dade County sheriff’s detectives, claiming, without a shred of evidence, that they had cut deals with Jacques’s four daughters from his first marriage. The detectives, he said, had agreed to manufacture testimony against Candace and Mel in return for a large under-the-table payment from the daughters, who wanted Candace convicted so that they could inherit Jacques’s estate.

As Foreman came to the end of the speech, he told the jury to look again at Candace, who was clutching a bouquet of flowers. “Let him among you without sin cast the first stone,” the attorney quietly said, then took his seat.

After three days of deliberation, the jurors returned to the courtroom to deliver their verdict. Candace was dressed in a beige suit and a white coat with gloves and sunglasses. Her face was “chalk white,” one reporter observed. Mel, who was wearing an olive-green suit, kept his gaze locked on the floor. When the jury foreman pronounced that Mel and Candace were not guilty, Mel leaned back in his chair and whispered, “Beautiful.” Candace convulsed into sobs. Later, in a back hallway, she kissed all twelve jurors. “Thank you,” she said. “Thank you for my children.”

One juror, himself in tears, said, “God bless you, ma’am.”

A crowd was waiting as Candace and Mel left the courthouse. Some looked on in shock, bewildered that the socialite and her young nephew had been set free. But a few women, weeping openly, tried to reach out and touch Candace. She was their heroine: a loving mother who had escaped the clutches of corrupt police detectives and prosecutors. “Candace, we love you!” they shouted.

Only ten days after the verdict was announced, a paperback book about Candace was published and shipped to stores across the country. A New York film company also announced plans for a major motion picture about Candace. Upon hearing this news, the mayor of Miami gave interviews saying he’d be happy to be cast in the film, playing the role of the judge.

Candace told reporters that she had no desire to have a movie made about her. She said she was ready to move on from what she described as “that unfortunate Miami episode.” Upon her return to Houston, she had an eight-foot-tall stone wall built around her estate to discourage gawkers. Yet hordes still flocked there. Tour buses even puttered by the mansion, the out-of-town passengers peering out the windows, cameras hanging around their necks. Occasionally, as a bus slowed in front of the electronically controlled front gates, someone would cry out, “There she is!” And for a moment, as a security guard waved his arms, shouting at the bus driver to keep moving, everyone would catch a glimpse of Candace standing by the front door.

River Oaks residents were horrified that she had stayed in the neighborhood. They stopped inviting her to parties and avoided the events she hosted. “Please—I wasn’t about to be seen standing next to that hedonist,” Joanne Herring told me. “She was a murderer. She had sex with her sister’s son. I don’t know which was worse.”

Candace, however, wasn’t going anywhere. When I talked to the former Houston Post society columnist Betsy Parish, she called Candace “the unsinkable Molly Brown,” a reference to the American socialite who survived the Titanic disaster. In fact, Candace told reporters that she would begin to focus on running the businesses she had inherited from her husband. As the new chairman of the board of Jacques’s bank holding company, she attended monthly directors’ meetings, accompanied by her financial adviser, Erle C. Cocke. (Candace referred to him in meetings as “the honorable Mr. Cocke.”) She oversaw the construction of another bank in Miami. When the new bank opened its doors, she was there, dressed in a cowboy hat, a fur-lined cape, and thigh-high boots.

Candace also purchased office buildings in downtown Miami, apartment buildings in Beverly Hills, oil and gas wells in Louisiana, and undeveloped land near the Alamo and Houston’s newly opened Galleria. She invested in a theatrical work called Lady Godiva. And she founded a music company to publish and promote the love songs she said she had been writing for the past couple of years to help manage her stress. Candace told Maxine Mesinger, the society writer for the Houston Chronicle, that Judy Garland was interested in recording a few of her songs. A delighted Mesinger promptly announced in her Big City Beat column that Candace was now writing pieces for the iconic performer and “shaping her career.”

Though the press tended to fixate on her love life and glamorous carousing, Candace was, in many ways, a woman ahead of her time. And it wasn’t just her successful tenure heading up a complex business empire. She stirred up even more media attention in October 1967, when she arrived with Mel in tow at a Houston benefit concert headlined by Aretha Franklin and Harry Belafonte. Proceeds went to Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and few members of the audience were white—segregation remained an entrenched part of life in the city. Candace, who’d made a sizable donation to the SCLC, sat close to the stage, posed with King for a photograph that ran in Jet magazine, and later hosted a dinner party at her mansion for King and the singers.

Candace also continued with other philanthropy. The Houston Post ran a large photograph of her later in 1967 as she broke ground for a $100,000 building project at the Boys Club of Houston. She was holding a shovel and, as ever, smiling eagerly. Candace got involved with the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo at the Astrodome, one of the city’s biggest charitable events. She made winning bids on the top steers and arranged to have her photo pasted on mammoth billboards, welcoming visitors to the annual show. The cowboys were intrigued by her. One admiring rider who got a look at her told a reporter, “She’d still make a pony pull his picket pin.”

The newspaper society columnists loved filling their columns with tidbits about Candace, especially if they involved Mel. The two of them were seen shopping in a neighborhood department store for light fixtures and curtains. They went to see a ball game. They were spotted in New York attending a Broadway musical. On a trip to Switzerland, Mel supposedly bought Candace an engagement ring.

Candace still insisted that she and Mel weren’t romantically involved. She loved him like she loved all of her relatives, she said. She rarely saw him, she added, because he was so busy starting a career as a commercial property developer.

It turned out Mel had a knack for real estate. One run-down building that he bought for $2,000 sold a year later for $110,000. He picked up other properties and hired a prominent Houston commercial real estate brokerage firm to manage them. His account was given to a young rookie broker, who told me that he and Mel hit it off, in part because he never asked Mel about Jacques’s murder. They began to meet for drinks. During one of their outings,Mel admitted that he was growing tired of Candace. “He said he was ready to move on but he needed to do it slowly, without setting her off,” recalled the broker, who’s now in his seventies and would speak only under the condition of anonymity. “Mel said Candace had a crazy streak. He said she was unpredictable and had a fiery temper and he wasn’t sure what she would do if she found out he had been with another woman.”

Candace was already suspicious that Mel was cheating on her. She once screamed at Mel in front of her children because she believed he was ogling a waitress. She got so upset with him on another occasion that she called the police and demanded he be arrested for hitting her “about the head and face with his hands and fist.” (When the cops found no evidence of assault, she dropped the charges.) She hired a private detective in Houston to follow Mel around and see what he was up to.

One afternoon, the broker told me, Candace’s chauffeur brought her to a building where the broker was working. “She rolled down the window and she gave me a nice smile. She was very well dressed. She asked if I knew where Mel was, and I said I didn’t know. I looked down and saw a .45 pistol on the seat beside her. I thought, ‘What the hell?’ ”

A couple of days later, the broker said, Mel told him he and Candace had gotten into another argument at the mansion. He went into her bathroom, shut the door, and walked over to the sink. Then Candace’s .45 went off three times, the bullets splintering the door. “Mel told me if he had been standing on the other side of that door, he would be dead,” the broker said.

Mel never filed a police report, and as far as I could tell, no one else in Houston heard about the alleged shooting. “Mel ordered me to keep it quiet, and I did,” said the broker. “I wasn’t about to cross him.”

Although they knew they would be bound forever to the mystery surrounding Jacques’s death, Mel and Candace finally decided to go their separate ways. Mel became Houston’s Hugh Hefner. He grew out his hair, sprouted a thick mustache, and frequented TGI Fridays, at the time an especially popular singles bar, wearing wide-collared shirts and custom-made jeans with leather stitching around the cuffs. “Even nice girls found him irresistible,” one woman who knew him told me.

As for Candace, by then in her fifties, she too had no shortage of love interests. “I remember going to one of her birthday parties that she threw for herself,” recalled the renowned Houston criminal defense attorney Dick DeGuerin, who in those years was just getting established. “It was in the backyard, around the swimming pool, and there was a lot of drinking. A friend of mine”—Jack Staub, the son of the Houston architect John Staub—“took off his clothes except for his boxer shorts and dove off the diving board, maybe to impress her.

“Anyway, she came floating down her spiral staircase, followed by another suitor, Buck Bukowski. Buck was barefoot, wearing this white Nehru jacket, smiling proudly. Candace stood on the outdoor stage with a microphone, and she said she had brought in a special guest to play for us. Out came Chuck Berry. We all applauded, and then Candace suddenly stepped forward and planted this huge, wet tongue kiss on him that must have lasted for thirty seconds. Candace and Chuck seemed to be having a really good time. I looked at Buck and thought, ‘Sorry about that, my friend.’ ” (Years later, in his 1987 autobiography, Berry would devote an entire chapter to his multiple flings with Candace, describing in detail their encounters on her circular bed.)

In 1971 she married again, this time to Barnett Garrison, a self-employed electrical contractor who owned a few local nightclubs. Barnett was a hulking fellow, six foot four and 220 pounds. He was 32. She was 51. They seemed happy together, at least until Candace learned that he liked to frequent a small nightclub that featured go-go dancers. One evening, after the club had closed, it burned to the ground. After a lengthy inquiry, Houston Fire Department investigators suspected that Candace had set fire to the joint. But they didn’t have evidence to arrest her, and the story never made the newspapers—that is, until years later, when Houston Post society columnist Marge Crumbaker asked Candace during a private conversation if she had started the blaze. According to Crumbaker, Candace waved a hand in the air and said, “I certainly would understand doing such a thing.”

In August 1972, a little more than a year after their wedding, Barnett was found facedown in a pool of blood on the Mossler mansion’s stone patio. His nine-millimeter automatic pistol, which he carried in a zippered case, was beside him. One of his shoes was beside him; the other was in the yard. He was still alive, barely. He had brain damage, a collapsed lung, broken ribs, and lacerations on his head. Police officers noticed scuff marks on the steep slate roof of the three-story home, which suggested that Barnett had fallen off the roof and plunged forty feet.

Two homicide detectives arrived and went to Candace’s bedroom to interview her. According to a police report, the door was locked, and initially Candace wouldn’t open it. When she finally allowed the detectives into the bedroom, she was incoherent, unable—or perhaps unwilling—to answer any of their questions. She mumbled that she had no idea why Garrison had been on the roof. At one point, she blurted out, “I already shot him,” but that made little sense because no bullet wounds were found on Barnett’s body. The detectives concluded that Candace was “either on medication or was highly intoxicated.”

Barnett’s fall was ruled accidental. But when I went to see Mickey Herskowitz, he told me a version of this story that’s never been reported. While he was researching his book on Candace, one of her relatives told him that Candace had paid two men to beat up Barnett after she’d discovered he was cheating on her. “What I was told was that after Barnett got pounded, he was still kind of belligerent, really tough as hell,” Herskowitz said. “So they ice-picked him in the ear, then took him up on the roof and threw him off.”

I called one of Candace’s relatives who’d been close to her during the early seventies. “What I heard is that Candace hired two of her cousins from Georgia—big, mean rednecks who drove bootleg liquor over state lines,”he said. “She told them she wanted them to come to Houston and teach Barnett a lesson, and that led to Barnett getting thrown off the roof.”

Barnett was taken to Methodist Hospital, where he lay in a coma. After six weeks, he regained enough memory to recall that he had graduated from Rice, but he didn’t remember being married to Candace or falling off the roof. When doctors said they could do nothing more for him, his parents took him in. Candace filed for divorce in March 1974, telling reporters that although she still loved Barnett, there was no way the marriage could last because his mother refused to let her see him. She said she had shown up at the Garrison home one night in a nightgown and fur coat, banging on the door with one of her high heels, but no one would let her inside.

She said she had no choice but to move on.

The suitors kept coming: a country music singer, a member of the Drifters R&B group, a prominent doctor at the Texas Medical Center, Sammy Davis Jr., a Houston television anchor, a young man who worked for a mortgage company. Just four months after Candace went to court to divorce Barnett, Mesinger trumpeted in Big City Beat that “a hot rumor around town has Candace Mossler and former mortgage man John Bradley planning a waltz to the altar in Italy.” No doubt to the relief of Bradley’s family, the wedding trip never took place.

Determined to reclaim her reputation, she hired Herskowitz to write her biography, promising she’d deliver the real story about who she was. But Herskowitz was unable to verify much of what she said. She told him, for instance, that she had been born in 1927 but that Jacques had doctored her birth certificate so that people wouldn’t realize how much younger she was. Herskowitz quickly realized the problem with that claim: that would have meant she was only twelve years old when she gave birth to her first child, Norman Jr.

Candace also told Herskowitz that she’d been diagnosed with polio when she was nine. She said doctors had told her she would never walk again, but after undergoing an arduous five-year routine of exercise, stretching, and massage, she’d rehabilitated herself and was finally able to walk without a limp. It was a dramatic story, and Candace teared up as she told it. Unfortunately, Herskowitz could find no one in the family who remembered Candace ever being afflicted with polio.

What particularly bothered Herskowitz was a lawsuit that had been filed in 1973, just as he started working on the book. Two of Candace’s adopted sons, Dan and Chris, who were then students at the University of Texas, accused Candace of converting large portions of their trusts to herself and of giving them just $350 a month for living expenses. They claimed she had promised them more money, but only on the condition that they agreed to quit school, get haircuts, and return to the mansion to work exclusively for her.

The court filings made it clear that life at the Mossler estate was hardly the fairy tale many newspapers had made it out to be. Chris said in a hearing that he’d left home as soon as he could because his mother would get high on prescription drugs and “didn’t know what she was doing and [would] tell outrageous lies.”

In 1975 Candace altered her will, leaving the bulk of the Mossler fortune to her eldest daughter, Rita. She kept Norman Jr. and her youngest child, Eddie, in the will. But she removed Dan, Chris, and Martha from any inheritance altogether, claiming they “have not demonstrated the care, love and affection I deserve as a mother.”

Herskowitz told me that the more he talked to Candace, the more he wondered if she was becoming unhinged. One day, she announced that she wanted to purchase the Houston Oilers football team. Another day, she said she’d met with a team of political consultants to explore running for governor. During a business trip to Miami, she called police to report that a masked bandit with “soft brown eyes” and “soft hands” had broken into her hotel room and taken $200,000 in cash and jewels. The police quickly closed the case, convinced her report was fabricated.

I tried to get Candace’s children, three of whom are still alive, to help me understand Candace, but none of them would talk to me. “My dad has spent more than fifty years trying to figure out who his mother really was, and he still has no answers,” said one of Candace’s grandchildren, Alex Mossler, an Austin-area general contractor. “I think he just wants everything to go away.”

Alex gave me a look and shook his head. “I don’t think anything will ever go away.”

In what was likely the last interview she ever gave, Candace hosted Mark Goodman, a writer for Esquire, at a party she threw at the mansion in early 1976. “Suddenly, at the stroke of one a.m., the lights dim to an intimate, cocktail room glow, the band tones down to a low background thrum and a spotlight sweeps dramatically to the hall staircase,” Goodman wrote. “Then, through the eerie gauze of cigarette smoke, a tiny, curvaceous, blond figurine begins to glide down the staircase à la Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard. As she descends, amid the tintinnabulation of cymbals and ruffle of drums, the glittering bandleader breathlessly announces, ‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, Mrs. . . . CANDACE . . . MOSSLER.’ ”

Goodman described Candace as “the all time all-American femme fatale.” That night she certainly put on the charm for him. After the party was over, she went to her bedroom and returned wearing what Goodman called “a breakaway pink gown.” Goodman wrote, “The voluminous Dolly Parton aside, she easily has the biggest chest of any female under five feet three.”

For the next six hours, Candace talked to Goodman. She also sang an original song that she said Chuck Berry thought highly of (“You’re a diamond, a flower, a ribbon, a rainbow / You’re the pot of gold people seek at the end of that rainbow”). When Goodman brought up Jacques’s murder, Candace claimed that the Dade County detectives, attempting to get her to falsely confess, had resorted to torture, tying her hands behind her back, cuffing her ankles, and shining lights into her eyes.

But all was forgiven, Candace said. “We have our sorrows and our heartaches, but you have to put that bridge behind you. I used to say to Judy Garland, ‘You’ve got to be like a cat, Judy. You’ve got to learn to land on your feet in this world.’ If that philosophy doesn’t get you a bluebird in every tree, I don’t know what will.”

In October 1976, three months after the Esquire article was published, Candace flew from Houston to Miami to attend a bank board of directors meeting. She checked into a suite at the Fontainebleau Hotel and called her Miami doctor, telling him she had a violent headache. He came to the hotel and injected her with Demerol, a painkiller, and Phenergan, a sedative.

Apparently, the doctor wasn’t aware that Candace had already ingested tablets of Placidyl, a barbiturate designed to treat insomnia. Her secretary found her the next morning. News reports noted she was dressed in a pink nightgown and lying “face down in one of five plush pillows spread about her bed.” The county coroner ruled that her death was due to an “incautious self-overdosage” of barbiturates.

Candace was 62 years old. “Candace Mossler Garrison Dies; Was Tried in Murder of Husband” was the headline in the New York Times. Candace’s son Edward issued a statement calling her “a perfect mother” who “did the best she could for everyone.” Her former attorney Percy Foreman, who’d gotten crosswise with Candace after her acquittal because she’d sued him over his legal fees, told the Houston Chronicle that Candace was an “intense egoist,” but he also described her as “a sympathetic character who had a feeling for the underdog.” Foreman revealed that Candace “hired me many times to represent people she didn’t even know just because of their plights that were revealed in the newspapers.”

Fewer than fifty mourners attended her funeral in Miami Beach, in the same chapel where Jacques’s service had been held twelve years earlier. Reverend John Lancaster, the pastor of First Presbyterian in Houston, traveled to Miami to officiate the service. He seemed to have been fond of her. He read the 23rd Psalm and told those who’d gathered to set aside, at least for that day, any negative thoughts about Candace. “She had a good side,” Lancaster said. “This is the time for remembering the good that God sent into our lives through Candace Mossler.”

The vice presidents of Candace’s banks were at the service, as were various friends and relatives from Georgia. Only two of the children—Rita and Edward—showed up. And to just about everyone’s surprise, Mel arrived, accompanied by his latest girlfriend.

By then, Mel had achieved real wealth. On top of one of the buildings he owned in Houston, he’d constructed for himself a luxury 20,000-square-foot penthouse, with a mirrored ceiling in his bedroom, a weight room, a rooftop swimming pool, and a pad for his helicopter. In Nassau Bay, a resort community near the Johnson Space Center, he’d also built a sprawling waterfront home, and he moored his 165-foot yacht, which was said to be one of the largest in the Western Hemisphere, in an adjoining lagoon.

Later, during the eighties oil and real estate bust, Mel would lose almost everything and end up in bankruptcy court, accused of concealing and falsifying volumes of documents relating to his assets. He took out full-page ads in Houston newspapers vowing to pay off his creditors. And though he didn’t get close to making good on his debts, he did make a comeback, focusing on housing, oil, and cement.

Mel died in 2010, at the age of 68. His autopsy report concluded he’d died of a form of pneumonia but listed a history of “possible prescription drug abuse.” The coroner also noted that there was “a prosthetic device” implanted in Mel’s “penile shaft.”

Not once did Mel ever publicly comment about Candace or the murder charges filed against them. Candace’s third husband, Barnett Garrison, never made any statement about her either. He failed to ever regain his memory and spent the last 25 years of his life in a nursing home before dying in 2009.

I’d assumed Candace had been buried in Houston, perhaps at the historic Glenwood Cemetery, which overlooks Buffalo Bayou and is where many of the city’s elite have their plots. It wouldn’t have surprised me if she’d arranged for a large mausoleum to be built over her grave so that future Houstonians would know who she was.

But it turned out Candace had made other plans. She’d ordered the executors of her estate to have her body shipped to Arlington National Cemetery and buried beside her second husband, Jacques Mossler. Candace had told them she wanted to spend eternity next to the man she loved.

This article originally appeared in the December 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Notorious Mrs. Mossler.” Subscribe today.