This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

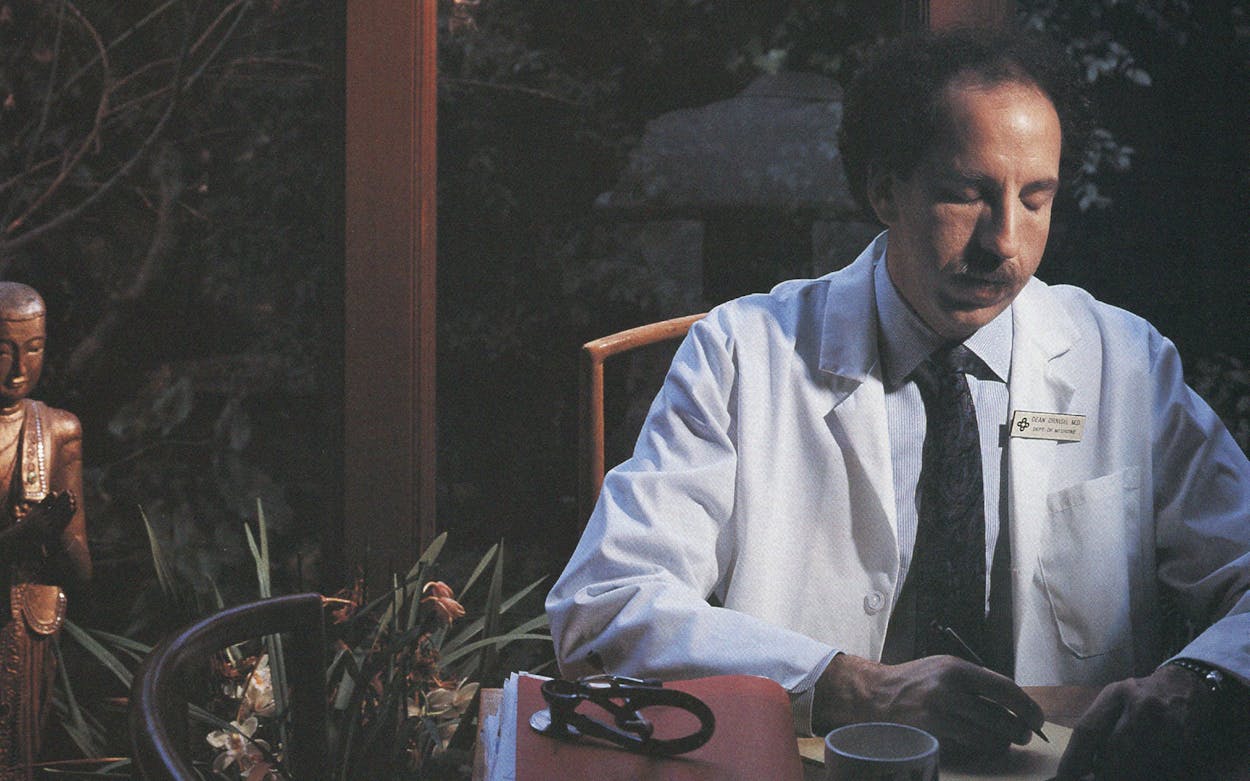

Please don’t call me a guru,” Dr. Dean Ornish asks. The voice is softly nasal but insistent, and in its request ignores the fact that Ornish has posed for both the Houston Post and People magazine meditating in the lotus position. But Ornish, 37, has no problem with contradictions. These days, he finds himself preaching that a person can reverse coronary disease and find inner peace by opening his heart according to the Ornish plan—“a different type of ‘open-heart’ procedure, one based on love, knowledge, and compassion rather than just drugs and surgery” —while the demands of celebrity have turned him into a whirling dervish. Curls lapping at his receding hairline, blue eyes doleful, moustache adroop, he spreads his message from his Sausalito, California, office, spinning from the VCR (to display for a visitor Ornish’s multiple TV appearances) to the fax (to dispatch the most recent Ornish heart-smart missive) to the copy machine (to duplicate myriad Ornish clippings) with enviable deftness. Just this brief exposure to Ornish reveals one essential truth: Unlike the people who have committed to the restrictive diet and coronary-care regimen that has made him famous, Dean Ornish intends to have his cake and eat it too.

The medical profession may scorn those they view as self-promoters, but Ornish, self-deprecating entreaties to the contrary, is unwilling to play the part of the mild-mannered medical researcher who toils in obscurity. Grave and unrelenting, he has propelled his book, Dr. Dean Ornish’s Program for Reversing Heart Disease, onto best-seller lists nationwide. The results of his study, which suggest that heart disease might be improved by a mixture of moderate exercise, a vegetarian diet, and what he calls “stress management,” have appeared not just in distinguished medical publications but in everything from New Age Journal to Newsweek. He presents papers at lofty medical conferences but also takes part in seminars at glitzy resorts like Rancho La Puerta, California, with feel-good forward-looking types like Gail Sheehy and Theodore Roszak.

If there is something oddly familiar about these methods, it is that Texas-born, Texas-educated Ornish is operating in the tradition of the rule-breaking Texas celebrity heart docs of the past few decades. What Michael DeBakey was to the sixties, what Denton Cooley was to the seventies, what Kenneth Cooper was to the eighties, Dean Ornish is to the nineties—the relentlessly driven medical star who takes on the conventional wisdom. Ornish, with his drug- and surgery-free method, challenges the high-tech, high-cost procedures of both Cooley and DeBakey, and with his noncompetitive New Age philosophy, decries the jog-till-you-drop regimen that brought Cooper such renown. Ornish has even managed to add one more interesting innovation: Although he talks up his Texas roots and travels to Houston regularly to meet with medical and business associates, he doesn’t live here. This Texas medical star makes his home in a three-story shingled Victorian overlooking San Francisco Bay.

“I am less concerned with what is easy than with what is true,” Ornish pronounces, a statement he uses to promote his method but that could also be applied to his consistently contradictory nature. One colleague, at pains to explain the secret to Ornish’s success, puts it another way: “Dean is a Whole Earth Catalog sort of physician,” he says, “but he can con everybody into everything.”

Bill Wilson is in mourning for a corned beef sandwich. He is slumped in a chair in Ornish’s office, staring at the floor, a 67-year-old former 747 pilot in a deep funk. A victim of heart disease, Wilson has, in the last month or so, noticed an increase in his angina after his daily walk. This information is important because Wilson is no ordinary patient. He is a member of Ornish’s ongoing Lifestyle Heart Trial, a four-year study that seeks to learn whether people who follow the Ornish plan can reverse their heart disease.

The much-publicized study and its spin-off, Ornish’s best-seller, are the reasons for his current status as both the darling of a cardiac-obsessed country and a devil among some established cardiovascular experts (Ornish is an internist by training). Last summer, in an article published in the prestigious British medical journal the Lancet, Ornish reported that after one year on his plan, subjects of his experiment showed a 5 to 9 percent overall reduction in the blockage of arteries leading to their hearts. While that finding may not have been enough to satisfy Ornish’s detractors—they say he jumped the gun, publishing a best-seller after completing a one-year study—it was enough to convince other doctors and the popular press that Ornish had found a way to turn heart disease around.

The study, now extended beyond the first year, is set up conventionally. Ornish recruited people with severe heart disease and randomly divided them into two groups. The first, a comparison group, was asked to follow their doctor’s advice, which, in turn, reflected the American Heart Association’s recommendations—to quit smoking, exercise moderately, and cut fat intake to 30 percent (the typical American eats 40 percent). This group can have fish, skinless poultry, and small amounts of beef. The second, or experimental, group follows the Ornish plan. Not only were these patients asked to quit smoking but they were also asked to exercise moderately for half an hour a day, devote an hour a day to stress-reduction techniques like yoga and meditation, and cut dairy products, cooking oil, and meat from their diets—poultry and fish, not just beef. They also attend four-hour group meetings twice a week. Ornish’s regimen, in short, makes the AHA recommendations look like a lavish picnic in the park.

Ornish believes that the AHA’s advice may be enough to prevent heart disease but not reverse it; drugs and surgery can be lifesaving in a crisis, but in many cases are not the best first choice. Many heart specialists counter that the Ornish program goes too far: Even if it’s healthy—and even with two ounces of alcohol allowed daily—the regimen sounds like condemnation to a supremely joyless existence. They say that it’s practically impossible to get people to change their habits even when their lives are threatened; vast numbers of people would never follow Ornish’s advice.

Wilson—a member of the comparison group, a.k.a. an ordinary cardiac patient—is certainly having difficulty. At this moment, frustration occupies his face. He complains to Ornish that he is much more careful about what he eats. He says that he has eliminated almost all red meat and has eaten only half a dozen eggs in the last few years. But after a deep, pained silence, the truth tumbles out: “I still like corned beef sandwiches,” he confesses weakly. Almost as bad from the Ornish standpoint, Wilson says he is still eating poultry. “Skinless, of course.”

“Fish?” Ornish inquires.

“Any way I can get it,” Wilson admits. It turns out that he eats chicken or seafood four to five times a week and uses some cooking oil every day.

Ornish’s manner is not judgmental as he jots this information in Wilson’s file, and perhaps it shouldn’t be. Wilson’s experience bolsters Ornish’s findings that following conventional medical advice will not necessarily make him better. With long, delicate fingers, Ornish scribbles a few more sentences and then studies his notes.

“Mind if I speak candidly?” he asks.

Wilson nods.

The patient is at a crossroads. Having completed several years in the study, he is scheduled for another angiogram and PET scan, tests which will reveal whether his heart disease is better or worse. Ornish tells Wilson that if the tests show he’s the same or better, he can have his corned beef. But if he’s worse, he may have to consider an angioplasty, bypass surgery, or bigger changes in his diet . . . like those advocated by the Ornish plan. “The pain is your teacher,” Ornish says somberly, referring to Wilson’s angina. “It reminds you that you still have a problem.”

As Wilson darkens, Ornish becomes even more solemn. “Whatever you choose is up to you,” he says. “I would never tell you to change.” Then he pauses. “Am I making sense?”

“Oh, yeah,” Wilson answers. “You always do.”

“I hope I can tell you you won’t have to change so much. I hope you can eat corned beef sandwiches sometimes.”

“Well,” Wilson says, sighing, “it looks like there are some interesting vegetarian cookbooks on the market.”

At this, Ornish’s gravity vanishes, replaced by cheerful, ferocious energy. “Oh, yes!” he says. “My book? Have you seen my book?” When Wilson shakes his head, Ornish begins to tell him about the tasty recipes collected there, with contributions from culinary stars like Wolfgang Puck and Alice Waters. Wilson is unappeased. “It’s not gonna taste like corned beef sandwiches,” he says.

Eventually Wilson gives in, agreeing to try the stricter regime. As he gets up to leave, Ornish offers him a hug. Then, holding his book open, Ornish asks Wilson one last question. “Would you like me to sign it?”

An ordinary member of the medical profession might avoid mixing medicine and marketing, but Ornish has never been an ordinary doctor. He wrote his book, he says, to share what he learned from his research and personal experiences. He says that he has struggled with many of the same stresses that heart patients do. Having become convinced that the emotional and spiritual aspects of heart disease are as important as the physical ones, he wanted to title the book Opening Your Heart but was overruled by his publisher. It is not only heart disease that intrigues him but the idea of pain itself—why we subject ourselves to habits such as overeating or drug abuse that bring us only physical and emotional misery. As a medical student, he was fascinated by the coronary-bypass operation because it became “a metaphor for the inadequacy of treating a problem without also addressing the underlying causes.”

Ornish uses his own pain as an example. He writes about his high-pressure, achievement-oriented childhood in North Dallas (“My parents very much wanted me to excel, especially in the academic arena—that’s probably why they named me Dean”) and admits that stress drove him into a suicidal crisis as a student at Rice University. He was terrified that he might flunk organic chemistry, jeopardizing his chances for admission to medical school. Sick with mononucleosis, Ornish retreated home. Because of his sister Laurel’s interest in yoga, his parents happened to be hosting a gathering for the world-famous Swami Satchidananda, who had come to Dallas to lecture. Ornish got the master’s life-is-being-not-doing message: He took up yoga, meditation, and vegetarianism—and adopted a new philosophy quite different from the competitive values with which he was raised. “The more inwardly defined I became,” he writes, “the less I needed to succeed and the less stressed I felt. The less I needed success, the easier it came.” He left Rice for the University of Texas at Austin, graduated with honors, and got into the Baylor College of Medicine. Five years later he began a low-key residency at the Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Still, Ornish is not advising his readers to roll over and mellow out. In the acknowledgments section of his book, for instance, he thanks not just Baylor and Harvard professors, but former Continental Airlines CEO Frank Lorenzo, the late editor-turned-healer Norman Cousins, and Hollywood mogul Peter Guber—a clue that he didn’t sit around waiting for success to find him. In truth, Ornish has grafted his openhearted philosophy onto an awesome entrepreneurial drive that in every way matches—or surpasses—that of medical stars like DeBakey and Cooley, as well as businessmen like Gerald Hines, a loyal Ornish backer. He has clearly meditated on what it means to be media-savvy (“This is off the record” could be his mantra) and has developed an uncanny ability to focus on people who can advance his cause.

That characteristic appeared early in Ornish’s life. His parents were prominent members of North Dallas’ prosperous Jewish community. Father Edwin was a successful dentist, mother Natalie determinedly pursued a variety of civic projects—she is the author of Pioneer Jewish Texans. From his earliest days, a lack of contacts was no impediment to his curiosity: When he was ten he talked engineers at nearby Texas Instruments into giving him spare parts for science-fair projects. Though he dabbled in photography and journalism before settling on a career in medicine, Ornish never abandoned the one skill that surpassed all the rest. “Even then he endeared himself to people,” recalls his father.

When Ornish reached Baylor in 1975, he effectively applied that talent. He came to the school at the height of its macho-medicine phase—the Texas Medical Center was then leading the world in the number of coronary-bypass operations. Consequently, preventive medicine was not a priority at Baylor, nor was a medical student who taught yoga and fought to remove the cigarette machines from the hospital lobby. “My inner voice told me Dean was a kook,” recalls one student, “but he was always a successful kook.” Ornish was no candidate for most popular: “He was a Type A guy trying to be Type B,” the colleague continues. “I remember finding his presence irritating.”

Even as he grew opposed to heart surgery, Ornish took a cue from its chief proponent, Michael DeBakey. Like DeBakey, Ornish began his life at Baylor as an ambitious outsider; also like DeBakey, he set about allying himself with people who shared his theories. Ornish cultivated Baylor’s new chief of medicine, Dr. Antonio Gotto, for instance, who was deeply involved in what was then a new field, the effect of cholesterol on the heart. In 1977, when, after his sophomore year in med school, Ornish took time off to run his first experiment in reversing heart disease—he wanted to sequester ten seriously ill cardiac patients and see if they improved on a regime of meditation, moderate exercise, and a vegetarian diet—Gotto was one of the few physicians to support him. (Early on, Ornish learned that language was important: When one professor advised him that the title of his study, “The Effects of Yoga and a Vegetarian Diet on Heart Disease,” might keep him from getting grants, Ornish changed it to “The Effects of Stress Management and a Low-Cholesterol Diet on Heart Disease.”) On Gotto’s advice, Ornish contacted Harvard’s noted preventive-medicine professor, Dr. Alexander Leaf, and offered to fly him to Houston at his own expense to witness the results of his experiment. (Leaf went, paying his own way; Ornish got into Harvard.) Later, Ornish upgraded his lab findings by enlisting the aid of Dr. Lance Gould, a Houston physician dedicated to promoting the PET scan, a new medical imaging system devised to replace thallium scans by more effectively measuring coronary blockages. Even DeBakey has served Ornish’s purpose. Ornish writes in his book and it has been repeated in countless news stories that, as a medical student, he assisted DeBakey in the operating room performing bypass surgery. (DeBakey grants that Ornish was one of the thousands of med students who rotated through Baylor’s cardiology service, but adds, “To say that he assisted me is ridiculous. He’s using my name—he’s an entrepreneur.”)

But the most important contact Ornish made was Dr. David Mumford, a garrulous, socially wired professor at Baylor. Like all researchers, med student Ornish needed money for that first experiment, but grants from established groups like the National Institutes of Health or the American Heart Association were out of the question. Ornish’s ideas were just too weird—except, that is, for the Houston society contacts Mumford introduced him to. Here, Ornish took a page from the book of Denton Cooley, who has developed a symbiotic relationship with haute Houston. Mumford directed Ornish to Susan Franzheim, for instance, the wife of former ambassador Kenneth Franzheim. An ex-flower child, she was open to Ornish’s New Age worldview. Through the Franzheim Synergy Trust she gave him $5,000.

Likewise, when Ornish needed hotel rooms for his first subjects, he was turned down repeatedly. That is, until encountering Daniel Dror, the socialite investor and owner of the Plaza Hotel. Ornish tried several approaches with Dror—everything from the betterment of mankind to a possible tax deduction—and Dror caved.

Ornish did get results —his patients felt better after thirty days, and, according to lab tests, more blood appeared to be flowing into their hearts. That conclusion was enough to persuade Ornish to launch a second study in 1980, after he completed school at Baylor. Again there were improvements—in Ornish’s patients, who this time bunked at the cushy Horseshoe Bay resort, and in his network.

His timing was fortunate. In the early eighties, Houston was awash in money, but it was also awash in wealthy, middle-aged men. These people had three reasons to be attracted to Ornish and his work. First, the med student’s determination appealed to their own unconventional instincts. Second, these CEOs wanted to reduce the ever-rising costs of health care in their businesses. Third, as another medical researcher puts it, “Rich guys want to live forever.” These Type A’s were entering the high-risk years at a time when preventive medicine was just coming into vogue among the upper classes. Nathan Pritikin’s heart-disease-prevention resort was then drawing more clients from Houston than anywhere but the Santa Monica area, where it was based; United Savings chairman Jenard Gross even hired a Pritikin-trained chef for a Mediterranean cruise. In Denton Cooley’s hometown, comparing bypass scars was becoming less and less chic.

As a medical student, Ornish had met and kept in touch with Henry Groppe, a rangy, soft-spoken petroleum consultant with his own firm and an interest in preventive medicine. Groppe’s contacts among Houston’s business leaders were extensive. Impressed with Ornish’s theories as well as his methodical approach, Groppe was quick to grasp medical-fundraising fundamentals. “I tried to think of people who might have a personal reason for being interested in this,” he says, meaning he made a list of people who had a history of heart disease or who had already suffered a heart attack. The most crucial interested party was Groppe’s close friend, developer Gerald Hines. Says Groppe: “It was the right thing at the right time for Gerry.”

Hines was a receptive audience—he had served on the board of Ben Taub General Hospital and was a Pritikin devotee (even so, he subsequently developed coronary problems). But Pritikin was not a physician, and the engineer in Hines was more comfortable with Ornish’s medical credentials and statistics. Through Baylor, Hines gave Ornish $50,000 for the 1980 study, and he eventually took a seat on the board of the organization he helped Ornish create, the Preventive Medicine Research Institute.

By 1984, Ornish had completed his residency and moved to San Francisco, where he started a third study—what would become the Lifestyle Heart Trial. Ornish wanted to test his theories in the real world, but he needed $50,000 a month to keep it going and was still having no luck raising money through established channels. Once again, Ornish looked homeward. Hines eventually guided Ornish to the Houston Endowment. At a meeting with endowment president, J. Howard Creekmore, Hines’s support of Ornish carried the day—Creekmore donated $350,000. (“I find you’re much more successful if someone at that level introduces you,” notes Ornish.) Groppe referred Ornish to Enron chairman and CEO Kenneth Lay, with whom he had served on the board of Transco. Lay was outspoken in his passion for preventive medicine (smoking is prohibited throughout Enron’s fifty-story corporate headquarters), and coincidentally, his father had recently had a heart attack. Ornish treated Lay’s father while he gave presentations to the Houston Club members and members of the Young Presidents Organization, who were not wowed by the vegetarian menu. And when PET scans were unavailable in California, Ornish prevailed upon Frank Lorenzo, then CEO of Continental Airlines, who provided Ornish’s patients with free transportation from California to Houston. Even when the bust hit and Hines advised Ornish that the local well was dry, the cadre of Houstonians came through. Lorenzo introduced Ornish to Drexel Burnham’s Michael Milken, who chipped in $10,000. (Ornish’s organization is now supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and two private foundations.)

It may be hard to believe such powerful strivers would be drawn to Ornish’s notion that “altruism, compassion, and forgiveness—opening your heart—can be a powerful means of healing the isolation that leads to stress, suffering, and illness.” It may also be hard to imagine such captains of industry twisting into yoga poses and gobbling up broccoli florets. Not to worry. Aside from Groppe, Ornish’s benefactors don’t necessarily follow his program. (Hines does meditate and watch his diet, though not surprisingly he isn’t hot for group therapy. “A lot of people need outside support systems,” Hines says. “I don’t.”) What captures their imagination has to do with an ethos more Texan than Northern Californian: the potential for expansion. “It’s all so exciting,” says Groppe. “We’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg.” With a visionary’s fervor, he speaks of setting up Ornish-based programs in every city. The coolly cryptic Hines waxes rhapsodic when he pictures Dean Ornish Dinners in grocery stores nationwide. A low-cost idea with the potential for saving—and making—millions. And a whole world in Dean Ornish’s image.

Tonight’s meeting of the 22 members of Dr. Dean Ornish’s Lifestyle Heart Trial seems unusually pressured. As always, this robustly cheerful, aggressively fit army of sweat-suited crusaders—the experimental group members and their spouses—has completed its brisk patrol around the marina at Fort Mason. As always, the participants have come inside a drafty restored building to complete their stress-management period. People who, five years ago would not have been caught dead waving their rear ends in the air in the yoga pose called the Sun Salutation, now do so twice weekly, following the Ornish plan. Likewise, they stretch out flat on their backs and put themselves into a deeply blissful state by tensing and relaxing their muscles in sequence. Soon the room fills with the sounds of people exhaling, with sighs, with moans, and occasionally, with snores that compete with the foghorns on the bay.

These are Ornish’s winners, ordinary people—a fireman, an investment banker, a priest—he has pushed and cajoled into joining the study. The rewards have been great. Not only do they feel better, but lab tests support their claims. One reason for their dramatic improvement may be that despite stringent rules, Ornish’s valuable charges are coddled in ways many healthy adults could only dream of. To help people stay on the program, a French chef, working with a nutritionist, prepares many of their at-home meals; a psychologist monitors their emotions; an exercise physiologist and a yoga instructor look after their bodies. The four-hour meetings enable members to help one another with group support. And of course Ornish is always there for them.

Tonight, however, Ornish’s attention is more sharply focused than usual, thanks to the presence of a group of honored guests: an influential cardiologist from Los Angeles, a German author of a satire called How to Have a Heart Attack, and this week’s journalists assigned to chronicle the progress of the Lifestyle Heart Trial. Watching them participate in the evening’s exercises, Ornish perches restlessly on an aluminum chair. The night is unseasonably cold, and so, in turn, is the room containing the crowd before him.

Anticipating their discomfort, Ornish soon converts his concern into action. He jetés out the door, and in what seems like a twinkling, tiptoes back into the nippy room, his arms laden with things soft and plush. Like a puppetmaster executing a supremely dicey maneuver, he tiptoes to each mat. A person who has not totally surrendered to the Ornish method would open one eye to see this: the doctor standing over him, shaking out a fluffy new blanket until it floats over his body like a benediction.

Such is life in Ornish’s carefully controlled environment, where it is crucial to keep everyone covered. While guests and charges were relaxing, Ornish had bolted into his aging BMW, raced a few blocks away to a store called Warm Things, used his American Express card as a deposit for the blankets, and then dashed back to shield the entire assembly from the cold. “Please be careful with the blankets,” he asks, as everyone arises refreshed and ready for their Ornish-devised vegetarian feast. “I have to return them.”

Dinner this evening is also quite a production. Hurrying his charges and guests into line, Ornish presents a cornucopia that includes artichokes drizzled with herbs, a lentil torte dozing in cabbage leaves, a gleaming leek mushroom-and-carrot terrine, a zesty red bell pepper stuffed with rice, and even a low-fat, naturally sweetened Floating Island. (The meals that members carry home in paper sacks are less appetizing. One man opens his bag to reveal a woeful brown concoction of rice and squash. “Our regular chef is on vacation,” he says glumly.)

After dinner, Ornish makes a few alterations in the standard group support hour because of the visitors. Arranging the chairs in a circle, Ornish suggests the guests ask questions. The members, many of whom could not cross a street without pain just a few years ago, give in to testimonials. “It’s the center of our lives,” one beaming woman says of the program. Another man wrestles to speak and then declares, “I’m grateful to Dean for taking me out of nonwellness.” The German author, a stout, jolly man who visited two years ago, says they have all changed radically. You smile now, he tells them, and you seem so happy with one another. “You’ve gone from Type A’s to Type B’s,” he says. “We’re the new Type C’s!” someone cracks, and everyone in the circle laughs, like old friends sharing a private joke.

At the end of the night, the group gets up to join hands, as usual. But tonight Ornish, oddly shy in front of visitors, holds back. Someone notices and, ending his isolation, grabs his hand and pulls him in.

Late for an appearance on a radio talk show, Dean Ornish speeds across the Golden Gate Bridge, praising the view, returning calls on his car phone, and discussing his work (“The point of our research is to help people make informed choices. I don’t ask people to change out of fear of dying, rather the joy of living”). Pulling into the station parking lot, Ornish refuses a parking place proffered by an anxious producer—noting two signs warning that it is a tow-away zone, Ornish allows that he would be “more comfortable” parking elsewhere.

He is to be a guest on Miller and Miller, a health and psychology show hosted by two therapists who are also husband and wife. In touch with the times, the show is sponsored by an addiction treatment center. Richard Miller is a tall, severe man with thinning hair, a thin upper lip, and the warmth of a mortician. Angela Miller looks like a nighttime soap star—pretty, with broad cheekbones and a lush mane of copper-colored hair; she wears dangling crystal earrings and a bomber jacket flecked with gold.

Over the show’s jazz intro, the Millers describe Ornish as the author of a “bestselling holistic book” and as the “president and director of the Preventive Medicine Research Institute—a long but very important title.” It takes Ornish little time to get into his rap and even less time for the Millers to get wrapped up in it. As he has told countless other reporters, Ornish begins with the drawbacks of bypass surgery (“So for me, bypass surgery became a metaphor . . .”) and talks about how the cardiac world is topsy-turvy, full of patients spending billions for surgery when many could spend nothing on a program like, well, his own.

“I noticed you lumped physical pain with emotional pain?” Angela interjects, once they are back from a commercial and a plug for the book. Ornish nods and launches into the “Pain is your teacher” soliloquy, resurrecting the agony of his early college years. “Aha,” Richard says soberly, “the Impostor Phenomenon.” Ornish stresses that the emotional and spiritual dimensions of heart disease need to be addressed as well as the physical ones. “I never tell people to change,” he intones. “I say these are changes that can improve the quality of your life right now.” People should realize how much better they’ll feel once they start eating properly. “I love the way meat tastes, having grown up in Texas,” he says, “but I don’t like the way it makes me feel.”

After another commercial (“When someone has a problem with alcohol or drugs or food —don’t wait . . .”), Angela brings up eating again. People have lost weight on the regimen, she prompts, because of its low-fat content. Ornish enthusiastically agrees—he’s talking abundance, not deprivation. “You don’t have to count calories!” he says expansively. “Eat!”

In closing, Ornish returns to his larger theme, which has less to do with reversing heart disease than freeing people from isolation. He quotes a patient who once told him that he had learned to care more about being open than if his arteries were open.

“That’s beautiful,” Angela says.

Afterward, she escorts Ornish to the exit, talking about her own health problems. “I notice when I eat more fat I sleep late,” she says, and then thanks Ornish again for being on the program and apologizes for its brevity.

“We’ll consider this a beginning,” Ornish tells her and departs with his autographed picture of the Millers.

Taking a shortcut across town (“Some bypasses are good”), he heads for Tower Records. After buying 25 gift certificates for Christmas presents and loading himself down with albums by everyone from Frank Sinatra to Jimi Hendrix, he gets an idea at the checkout counter. “If you buy tons of stuff, do you get a discount?” he asks the clerk. The store is packed, and a line has already begun to snake behind him. The cashier surveys the line and scrawls something on a piece of paper; he tells Ornish to apply for a discount at this address. Ornish studies the piece of paper and then fixes the clerk with a friendly look. “Can I see the manager?” he asks. The line behind him blossoms, a fact not lost on the cashier, who tells Ornish that the manager is extremely busy. Undeterred, Ornish asks the clerk if the manager could possibly see him for just a minute. Another clerk is drafted for the errand and returns with news that the manager is indeed “very busy.”

“I’ll wait,” Ornish says.

Shortly, the manager—a stocky, bespectacled, irate man—appears. He listens impatiently as Ornish makes his pitch for a volume discount, and for about ten minutes the two argue about whether Ornish is a member of a nonprofit organization or a student, either of which would get him the store’s price break. In a rare defeat, Ornish capitulates, accepting the same address the clerk had offered him half an hour before. All is not lost, however.

“Do you do a lot of radio?” a cashier asks, eyeing his signature on the check.

“No,” Ornish says. “Why?”

“Your name is familiar.”

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Medicine

- Longreads

- Houston