This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

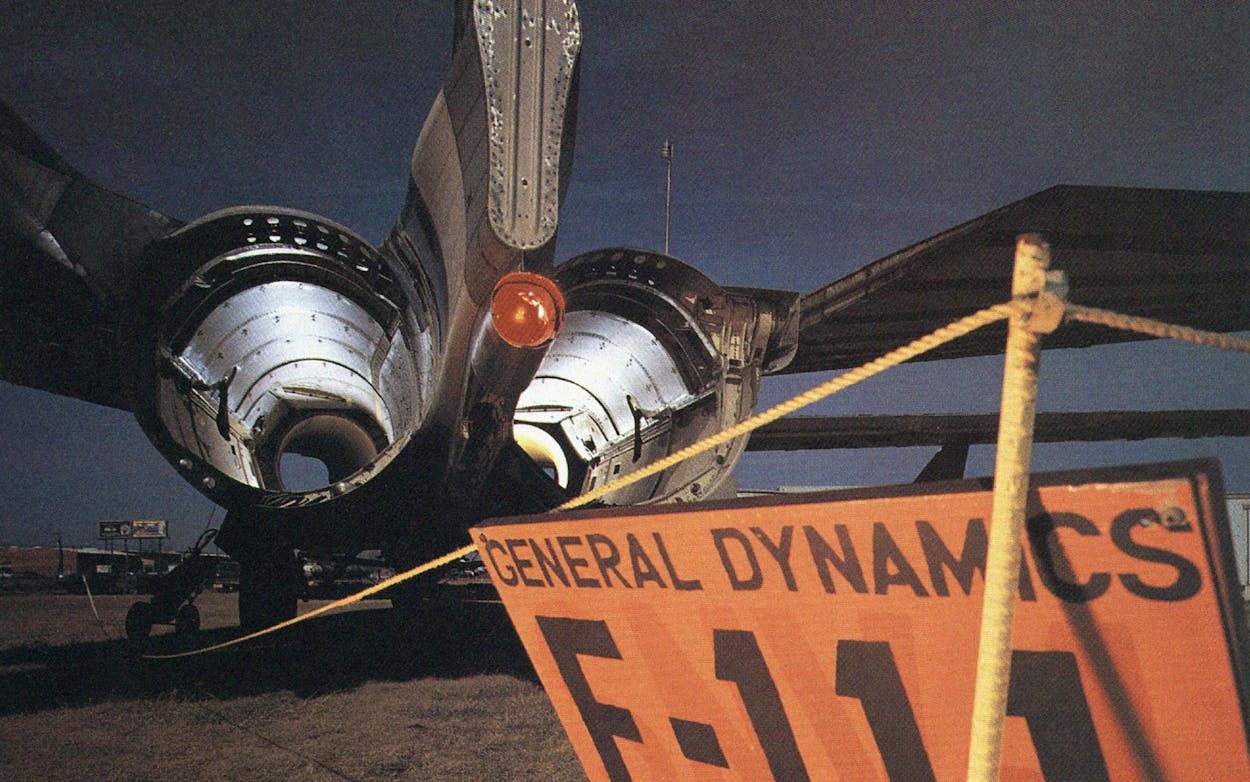

Outside the gates of the General Dynamics plant in Fort Worth is a squalid little roadside museum for cast-off warplanes. Here one can examine the long-necked carcass of a B-36 Peacemaker, the first intercontinental bomber and the last of the propeller-driven behemoths of the Strategic Air Command; the delta-winged B-58 Hustler, still the fastest bomber ever built, even though it was retired from service nearly twenty years ago; and the needle-nosed F-111, with its distinctive retractable wings.

Each of these planes was constructed in the mile-long assembly building of the General Dynamics Fort Worth Division. One can stand here at the Southwest Aerospace Museum and view the rusting history of military aviation since World War II, while overhead the airplanes that make up the fleet of the modern United States Air Force—the B-l, the F-15, and especially that petite but muscular acrobat, the General Dynamics F-16—roar off the end of the runway that GD shares with the adjacent Carswell Air Force Base.

Welcome to the military-industrial complex. This particular plant is one of 1,339 military contractors in Texas, and one of 120 in the city of Fort Worth alone. Always among the top defense companies in the nation (last year it was number two behind McDonnell Douglas), General Dynamics likes to boast that its programs form the “heartland” of America’s defense needs. It is the only contractor to supply major weapons systems to all three military services. In several locations in California, GD makes Tomahawk cruise missiles, air-to-air Sparrow missiles, and ground-to-air Stinger missiles. In Groton, Connecticut, GD builds Trident submarines for the Navy. Outside Detroit, in Warren, Michigan, GD puts together Ml Abrams tanks for the Army. But its most important and most profitable contract—in fact, the largest defense program in history—is the manufacture of F-16 Fighting Falcons here at the Fort Worth Division. Thirty-two thousand people work at this plant day and night, seven days a week. To date, they have assembled 2,516 F-16’s, costing about $20 million apiece.

I came to Fort Worth to see what was happening to one of America’s premier defense contractors on the morning after the cold war ended. It was a jubilant period in the world. People everywhere were celebrating change. The Red Army Chorus was serenading President Bush on the White House lawn. The Berlin wall was being chiseled into concrete nuggets and sold by the ounce at Foley’s. One by one the countries of the Warsaw Pact were renouncing communism and rushing into the Western embrace. Meanwhile, in Washington, legislators were speaking hopefully of massive cutbacks in defense expenditures. How was the defense establishment reacting to such epochal events? This was a question that would have profound implications all over the world, but nowhere more than in Fort Worth, where GD’s billion-dollar annual payroll accounts for more than a third of the city’s nonmilitary wages.

Indeed, as good news poured in from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, the economic prospects for Texas began to look increasingly dire. For the past five years, the only real bright spot in the state’s dismal economy has been the steady increase in military spending, which has grown four times faster than the economy overall. Now nearly one out of ten people employed in Texas works in the defense sector.

With the cold war over and the prospect of unprecedented cutbacks in defense spending, many people have begun to speak hopefully about a “peace dividend.” Looking at the defense establishment in Texas, however, one sees that our real investment is in war, not peace.

To understand General Dynamics, one must realize that it is not just a company, it’s a culture. Practically everyone I met at GD has a relative working here. Fathers and sons, mothers and daughters—families with four generations are scattered through various departments. Even employees who are not related are knit together through other ties. They go to the same churches and join the same clubs. Their children go to school together and play on the same soccer teams at the company recreation center. Their social lives tend to revolve around company parties. In some respects, going to work for General Dynamics is like entering a religious colony. There is the world outside, the world of flux and uncertainty, but also perhaps of hope; and there is the windowless world inside the security gates.

“It’s like there is a big glass dome over people that work at GD,” observes Renee Nombrana, the chief clerk in the logistics department.

Renee has grown up in the GD culture. Her father is an engineer who worked for the company for thirty years. She lives in Wedgwood, which is known as a GD neighborhood, even though it is all the way across town from the plant. “The truth is, you can’t live anywhere in this city without finding neighbors who work at GD,” says her husband, Gilbert, who is a function leader in the procurement office. “People wait in line to get a job with that company.”

Indeed, both Renee and Gilbert Nombrana struggled hard to get their jobs at GD. Renee was attracted by the company’s benefits and rather high rate of pay, “plus it seemed like a glamorous place to work,” she adds. Renee would have liked to work in the assembly area, but every time she applied, she was asked to take a typing test. After failing the test seven times, Renee quit her job at a bank and spent the next four months at her dining room table, practicing on a borrowed typewriter. She finally passed. “Now I feel part of a selected few,” she says.

Like many other GD workers, Gilbert was drawn to the company because of his lifelong passion for airplanes. Before he caught on at the plant, he worked briefly as a baggage handler at Love Field, just to be close to the aviation industry. “Every once in a while I’d get to look in the cockpit and see where the pilots sit,” he recalls. In 1978 he heard that GD was hiring, and he put in an application. He began as a quality-assurance inspector at $6.10 an hour. Taking advantage of the company’s education and training programs, Gilbert advanced himself into a salaried position, where he now makes “a really decent living.”

The Nombrana family is one of thousands in Texas whose lives depend on military spending. Their employer happens to be the largest military contractor in the state, receiving $3.5 billion in contracts from the Department of Defense in 1989 and $9.5 billion in total sales. That $3.5 billion was only a portion of the $29 billion in military contracts awarded to Texas firms last year—$24 billion of which was spent in the Metroplex. In the past, military spending in Texas primarily has been in the form of wages to the more than 100,000 active-duty servicemen stationed at the state’s 44 military installations and to the additional 200,000 civilians and retirees on the Pentagon payroll. In the eighties, however, with the help of a powerful congressional delegation in Washington, Texas has made itself into a defense-industry power. After General Dynamics, the major defense industries in the state—the ones with the billion-dollar contracts—are Bell Helicopter Textron, which is also in Fort Worth; LTV in Grand Prairie; Texas Instruments in Dallas; E-Systems in Greenville; Lockheed in Austin; and Rockwell International in Richardson. Behind those companies are innumerable subcontractors and vendors; GD alone paid out $360 million to more than 2,500 Texas businesses in 1988.

Known as the “bomber plant” when it was completed in 1942, the 4.9-million-square-foot assembly building was briefly the largest air-conditioned structure in the world until the newly finished Pentagon eclipsed it in 1943. Back then, Rosie the Riveter was putting together B-24 Liberators for Consolidated Aircraft. Those planes would carry the air war to Germany and provide cover for the Normandy invasion. Today Air Force Plant No. 4, as the government-owned building is officially called, is still provided rent-free to Consolidated’s corporate heir, General Dynamics.

Except for some of the high-tech robotics and the fact that the final product is a sexy little fighter craft rather than the lumbering olive-drab bomber of old, the plant is little changed since the World War II era. Under the bluish cast of sodium-vapor lights six stories above them, workers still pedal the 640 antiquated fat-tired bicycles through the massive flag-draped assembly area, which is the length of seventeen football fields. Employment levels are higher now than they were even during the wartime peak of 30,000, although today there is a greater percentage of salaried white-collar workers and fewer women on the production line.

“It takes roughly nine months from the cutting of the first piece of metal to the point where we’ve got a finished plane,” GD spokesman Z. Joe Thornton tells me as we ride through the facility in an electric golf cart. We begin at the south end of the plant, where aluminum sheets stacked two stories high wait to begin their transformation into the hottest fighter ever made. Although no F-16 has been involved in American combat, GD sells the plane to fifteen other nations, and so far the F-16 has recorded more than fifty kills in aerial combat without a single loss—an unparalleled record of military dominance. But that is not the Fighting Falcon’s only claim to excellence. It boasts the highest reliability and lowest maintenance requirements of any fighter. A fighter craft designed to double as a bomber, it has won every major bombing competition it has entered. According to company legend, when the Israelis used F-16’s to bomb an Iraqi nuclear power plant, the bombs dropped by the second aircraft went through the holes left by the first. On the east wall of GD’s assembly building is a sign reminding workers that Fortune magazine named the F-16 one of the top one hundred quality products in the world.

“The two things most people say about the plant when they visit it the first time are how clean it is and how quiet it is,” Thornton says. We are traveling north down the central aisle. As we proceed, the angular aluminum parts begin to assume the coherent shapes of wings, tails, and portions of the fuselage. Near the end of the line, in Department 140, we come to the mating section, where the three parts of the fuselage are fitted together inside a spiderweb of scaffolding and where complex avionics packages are installed. When the body of the aircraft is complete, it is rolled across the aisle to receive its wing and tail assemblies. There Dave Wasek, a big blond former roustabout, bolts on the abbreviated wings, which in the F-16 double as fuel tanks. “I’ve been doing this for three years,” says Wasek. “It’s the first time I was ever in a factory.” Wasek enjoys his work, but he admits, “I do miss the out of doors.”

After Wasek hangs the wings, the completed shell of the aircraft goes to Jerry Harris, one of the structural mechanics who examine the completed assembly and check for faulty connections. Harris came to GD thirteen years ago, after he was laid off at Bell Helicopter. “The opportunity for advancement was greater here,” he says, “and just being a part of the F-16 program is a rewarding experience.” After he finishes his examination, Harris oversees the installation of the twenty-foot-long, 3,700-pound General Electric or Pratt and Whitney engine. One of the “plumbers” in the department, such as Jack Darter, will slide the engine off its trolley and into the waiting cavity. “It’s a damn tight fit,” says Darter, “but after you work on it for ten or fifteen years, it gets pretty simple.”

At the end of the line, half a dozen F-16’s are waiting to be crated and shipped off to customers. Although the U.S. Air Force has been GD’s main customer since the first F-16 came off the line in 1978, the plane is the mainstay of several NATO forces, as well as Venezuela, South Korea, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Egypt, and Pakistan—which happened to be the destination of several planes that were completed on the day I visited. GD’s newest customer is Bahrain, a country the size of Arlington that has just ordered twelve aircraft. In a controversial agreement with Japan, GD will share some of the F-16 technology in the construction of the first modern Japanese-built fighter, the FS-X.

It is no wonder that air forces around the world are dying to get their hands on the F-16. Not only is the plane a highly reliable weapon, but it also is an elemental work of aerodynamic art. Like its namesake, the falcon, the F-16 is built for agile maneuver. The cockpit is so far forward that pilots say they feel like they are riding on top of the plane. Sitting here with its canopy swathed in masking tape as it waits to go to the paint shop, the stubby-winged craft demands one’s admiration for its simple design and its precise construction. Viewed from the side, the feathered lines of the craft make it appear tense and curious, dangerously expectant, like a cat peering into a mousehole. Studied from the front—that is, looking straight down its white gullet—there is a menacing but also weirdly humorous quality about its probing needle-nose and its gaping jet intake, which resembles a clown’s painted grin. Packed with electronic brains and a supersonic heart, it has become the most versatile warplane in aviation history.

And yet it is exactly history that is facing General Dynamics and its elegant product now. For all its current glory, the F-16 eventually will join the other relics in the Southwest Aerospace Museum. GD is anticipating that day by designing the next generation of advanced tactical fighters for the Navy and the Air Force. In the world outside the windowless walls, however, such extraordinary changes are taking place that even the Pentagon has begun to reassess its future defense needs, and Congress is talking about huge cuts that go well beyond what Defense Secretary Richard Cheney has proposed. Already several major contractors have begun scaling back: Lockheed recently laid off eight thousand workers from its plant in Marietta, Georgia; Northrop cut three thousand jobs; Hughes Aircraft trimmed six thousand; other giants such as Litton Industries and TRW have cut back as well. Meanwhile, every social agency in Washington has its fork on the table, ready to dig into the military pie. In such a climate, it is hard to imagine anyone believing that the defense budget and the industry it feeds will continue at the extraordinary levels achieved during the Reagan years. But in the world inside GD, this is the golden age, the age of hungry customers and fat contracts and plenty of lucrative new defense contracts just over the horizon. Here, the game goes on, the cold war never ends.

Like so many modern corporations, GD is a conglomerate of several different companies, each of which has absorbed other smaller enterprises, so that a chart of the corporation’s mergers and acquisitions over the years reads rather like the family tree of the American arms industry.

The founding division of General Dynamics began more than a hundred years ago as a small manufacturer of electric motors and batteries. In 1880, the year Edison patented the electric light bulb, a company named Electro Dynamic began making electric motors and batteries in Philadelphia. The Industrial Revolution was just beginning to exploit this amazing new power source. Soon another fledgling business, the Electric Launch Company, acquired Electro Dynamic to supply motors for its pleasure boats. Then in 1889 Electric Launch acquired the Holland Torpedo Boat Company, which was developing the U.S. Navy’s first operational submarine. Electric Boat, as the new company came to be called, quickly dropped its commercial product line and concentrated on building submarines.

In 1954, General Dynamics—as the company was then called—merged with Convair, a giant aircraft company that claims a lineage stretching all the way back to the Dayton-Wright Company, which was started by the Wright brothers to supply airplanes to the U.S. Army. But the real father of Convair was Major Reuben H. Fleet of the Army Air Corps, an energetic barnstormer and nonstop talker who earned the reputation, through his relentless self-aggrandizement, as the most boring man in the history of aviation. In 1918 Fleet began the nation’s first airmail service between Washington, New York, and Philadelphia. After World War I, Fleet worked briefly as general manager of the Gallaudet Aircraft Corporation before stealing away one of Dayton-Wright’s best designers and beginning a company called Consolidated Aircraft in a small factory in Rhode Island.

A few months after the United States declared war on Germany and Japan in 1941, Fleet was nudged from the helm of Consolidated by government officials who considered his boisterous style of management unsuitable for wartime. Consolidated merged with Vultee Aircraft, which begat Consolidated Vultee—a name that was eventually restyled as Convair. During the war, Convair built an astounding 33,000 aircraft, many of them at the immense new plant in Fort Worth. “By the time it merged with General Dynamics,” writes Jacob Goodwin in Brotherhood of Arms: General Dynamics and the Business of Defending America, Convair “had captured a unique place in the hearts of most Americans who had lived through World War II.”

After World War II, the Korean Conflict soon followed. But more important, from the point of view of companies such as General Dynamics, another war had begun that seemed never-ending—the cold war. In response to the communist threat, Americans conceded the need for a permanent defense establishment, one that would grow and prosper even without the immediate threat of military engagement; moreover, one that would lead the country into an ever more expensive and frightening arms race.

During this period the world inside the windowless walls and the world outside them began to drift apart. To some degree, it was the paranoia of the times. The Fort Worth Division resembled an armed encampment with anti-aircraft emplacements; the fences were patrolled by guard dogs. Inside the plant, workers were not just building weapons of war, they were making the tools of apocalypse—long-range bombers designed to carry nuclear weapons to the Soviet Union. Many of the bombers were stationed right next door at Carswell Air Force Base, which was a significant link in the Strategic Air Command. Every day those ponderous leviathans, the B-36’s, would take off from Carswell with their fateful cargo. In the meantime, the city of Fort Worth, which had always been commercially acquainted with death through its famous stockyards and slaughterhouses, began to accustom itself to being a different sort of town, one that made its money by delivering death from above—a suburb of Armageddon.

As a whole, the defense industry has become less diversified and increasingly dependent on its single unpredictable but also patient and forgiving customer, the Pentagon. In this relationship, it is always a seller’s market—one that military contractors have too often taken advantage of. Indeed, when people think of military contractors these days, what comes to mind are fabulous cost overruns and unconscionable charge-offs that have made the defense industry synonymous with greed, corruption, and arrogant management. In the past, GD was one of the worst offenders. It was GD that in 1983 tried to bill the Air Force $9,609 for a 12-cent Allen wrench, which would have been used to adjust the F-16’s radar. That wrench became a symbol of the insolent attitude of an entire industry. Subsequent congressional investigations uncovered a pattern of overcharges by GD that was more than twice the average of the Pentagon’s top two hundred contractors. GD was routinely billing the government for such items as Fighting Falcon tie clips (at a total cost of more than $300,000), country club memberships, expensive artwork for corporate executives, rental Cadillacs, a $150,000 company party, and so on. There was even a $155 kennel fee for boarding a dog while a GD executive spent time in a South Carolina retreat. These revelations produced a number of reforms in the Defense Department. They also cost David S. Lewis, GD’s chairman at the time, his job.

Lewis was replaced in 1985 by Stanley C. Pace, then vice chairman of TRW. Under Pace, GD inaugurated a new ethics policy. In the latest government probe of defense-industry corruption, Operation Ill Wind, GD was untouched.

In the world outside the windowless walls, the scandals of the past have left many critics feeling that as the cold war ends, companies such as GD should simply be left to collapse from their own weight. “I don’t give them any sympathy,” says Jay Miller, an Arlington aerospace publisher. “They’ve been greedy for so long, and they’ve had plenty of opportunities to project the changes in the world and correct their ways. They’ve simply failed to do it.”

But Miller understands how important companies like GD are to the Texas economy. “Defense spending is supercritical here, especially in the Metroplex. It’s not just GD. There’s Bell, there’s E-Systems, there’s thousands of subcontractors—a major cutback will have a catastrophic effect in this area. The bottom line is that it’s going to take a region that is already modestly depressed and push it beyond modest.”

Lloyd Dumas, a professor of political economy at the University of Texas at Dallas who has written extensively about the defense industry, says, “The defense cuts may be small at the beginning, but it’s going to be increasingly difficult to sell to the American taxpayer the idea that he needs to continue shelling out money for a fighter jet that would protect him from an enemy he can’t even see.” Barring a sudden return to the aggressive Soviet policies of the past, Dumas predicts a steadily declining defense budget for the next several decades. “By the year 2000, it’s conceivable that the U.S. military will be less than half the size it is now—I mean troop strength, arms, procurement, the whole thing. Ten years after that, assuming we’ve succeeded in negotiating arms agreements and have built up a history of abiding by them, there will be an entirely different attitude in terms of how much we trust each other. In that kind of world, taking down what remains by eighty percent becomes thinkable.

“You could say we’re at a fork in the road. If the defense industries fail to pay attention to the shift in military spending, then they’ll be unable to switch to civilian production.

“But what makes me optimistic is that I know the management and workers at these places. They are good, talented, skilled people. If they get serious about retraining themselves for a civilian economy, then they could lead us to the greatest economic revival since the Industrial Revolution.”

Several years ago word came down from the corporate headquarters in St. Louis that, come what may, General Dynamics would continue to concentrate on the defense business. Other companies were exploring the possibility of diversifying their product line. Some, such as Eaton Corporation, decided to get out of military contracting altogether. But GD chose to continue on the path it had been on for the past hundred years. That decision was followed by years of record-breaking sales and profits.

In large part, those profits have come from the Fort Worth Division, which is headed by Charlie Anderson, a somber-looking man with beleaguered eyes and a wide, down-turning mouth. “As a peace-loving citizen of this world, I am pleased to see the easing off of tension, but I am pragmatic enough to believe that there will never be an end to our defense requirement,” Anderson says as we chat in his spare, mahogany-paneled office.

Anderson expects hard times for the defense industry. He has seen them in the past—such as in 1972, when the F-111 project came to an end and the company shrank to 7,200 employees. “We almost turned out the lights,” he says. “We didn’t know if we were going to turn the plant into the world’s longest bowling alley or the world’s largest mushroom factory.” But bleak times are a part of GD’s past, not its future, Anderson insists. He expects the division to prosper by continuing to upgrade existing F-16’s; by building up a stable base of the A-12, the new stealth fighter it is designing with McDonnell Douglas for the Navy; and perhaps by winning the contract in conjunction with Lockheed for the new fighter the Air Force longs for, the ATF. “In ten years I expect us to be about as busy as we are today—even in the face of declining defense programs,” says Anderson. Other companies will suffer, but not GD. “There’s no other aerospace company in the world like it,” he says proudly.

The view in Washington is far less rosy. “GD is whistling past the graveyard,” one congressional staffer in the Texas delegation recently told me. He cited Bell Textron’s V-22 Osprey, the vertical takeoff aircraft that Defense Secretary Cheney canceled, despite congressional support for it. “All the big programs our contractors are involved in are in trouble,” the staffer pointed out. “That’s particularly true of new programs such as the A-12 and the ATF.” The reason Cheney cut the Osprey, said this veteran budgeteer, is because new programs have fewer defenders than established ones. “That’s why you cut a V-22; it’s also why you may cut a next-generation fighter.” It doesn’t help the chances of the A-12 program that the projected costs have been skyrocketing—now up to nearly $120 million a plane, according to Defense News, with some estimates as high as $200 million.

Even the F-16 is in trouble. Last year the Pentagon ordered 180 of the planes. Cheney tried to cut that to 120. Congressional resistance salvaged about half the F-16’s Cheney had hoped to cut, but it signaled that established programs with powerful political constituencies also would be facing cutbacks, if not outright cancellation (as Cheney attempted to do with Grumman’s F-14 fighter). It’s also true that GD’s political horsepower has diminished considerably since the disgraced departure of two of its strongest champions—House Speaker Jim Wright, who was the representative from GD’s Fort Worth district, and former Texas senator John Tower, who had been nominated for Secretary of Defense.

What seems to be the obvious choice for GD is to explore products that are not dependent on the military budget. That is something the company is loath to do. Since World War II, its only previous experience in reaching out to the civilian market, beyond some limited mining interests, was to purchase the ailing Cessna Aircraft in 1985. “I was real proud when GD bought Cessna,” says union leader Pat Lane. “I thought that they would finally be getting into the commercial side of the business. However, one of the first things management did was to dismantle Cessna as a commercial aircraft company and turn it into a military contractor. They quit building all the single-engine aircraft. Cessna probably will never come back now—and it was once the leading light-aircraft manufacturer in the world.”

Over in the Experimental Hangar, an imposing steel building behind the plant, Jack Buckner is the vice president in charge of special programs. Here is where the F-16 was born and where the A-12 is being developed. Balding and square-jawed, Buckner bears a strong resemblance to the actor George C. Scott. It’s Buckner’s job to design new weapons systems that respond to changing threats to our national security. As the nuclear standoff becomes less acute, Buckner sees a possible rise in low-intensity conflicts—that is, guerrilla or urban warfare. “We have to think of changing our mindsets about what kinds of conflict we’ll have to be prepared for,” he says. “It could bring on a whole new class of weapons.”

The one largely nonmilitary project Buckner is working on is the National Aero-Space Plane, otherwise known as NASP or the X-30. This amazing vehicle would take off horizontally, like a regular airplane, then achieve speeds up to 25 times the speed of sound as it bursts free of the atmosphere. The model Buckner holds in his hand looks like a swollen dagger. “Right now, the lift-off gross weight of the space shuttle is four-and-a-half million pounds. The goal of the X-30 is to reduce that load to one tenth of that, and still carry comparable payloads. It’s an unprecedented challenge.”

I ask Jack Buckner if he ever thinks about making a commercial project—something other than warplanes. I am thinking of GD’s counterpart in the Soviet Union, Sukhoi, a state enterprise that produces the SU-25 and SU-27 fighters but that is now also making toasters and bicycles. Recently, Sukhoi proposed a joint venture with the Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation, a Chrysler subsidiary, to build a new generation of supersonic jets. It’s the next logical step in the world of commercial aviation.

“Some of us in this division would love to have that opportunity,” Buckner admits. “Something like a supersonic commercial transport—I know we could do an admirable job on that. But the front-office judgment is that there’s a culture associated with any customer-product combination. We know our culture. If we venture outside it, we’d be taking a big risk. After all, what makes a commercial transport a success is a totally different equation from what makes a military weapons system a success . . . such things as the operational cost per seat, the load factors, the fact that those airplanes have got to fly around the clock. That’s a whole different culture, one that we’re not familiar with, and the investment required to become a member of that club is thought to be pretty astronomical. Of course, that doesn’t change the fact that there are a lot of people around here who’d love to turn their creative juices toward it.”

Ultimately, the weight of the decisions GD makes about its future will fall heaviest on families such as the Nombranas—people who have given their lives to the company. “I want to retire at GD,” says Gilbert. “I’m forty-three years old now, and I hope to put in another twenty years.” Renee feels the same way: “I either want to work at GD or stay at home.”

I was visiting the Nombranas in their home one evening in Wedgwood. Their two daughters, Ashley and Amy, were just getting out of the bath. Ashley, who’s three years old, is just learning to read, and Renee had covered the living room with placards saying “table,” “chair,” “television,” and so on. I took a seat on the “couch.”

“We’re just a normal American family trying to make a living,” says Gilbert. “GD has given us a chance to make a good life for ourselves and our children, and for that I thank them. I feel like I’m finally where I want to be in life.

“Yet in the back of my mind, I know things are changing. I wake up every morning and hear the news. I listen to all the things that are happening now—in Russia and Poland and everywhere. I know that means we’re going to be cutting our defense budget. And eventually that is going to affect us. If it’s for the betterment of the world, so be it. Right now, we’re just going to make the best of what we have while we have it. I know as well as anybody it can’t last forever.”

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Military

- Longreads

- Fort Worth