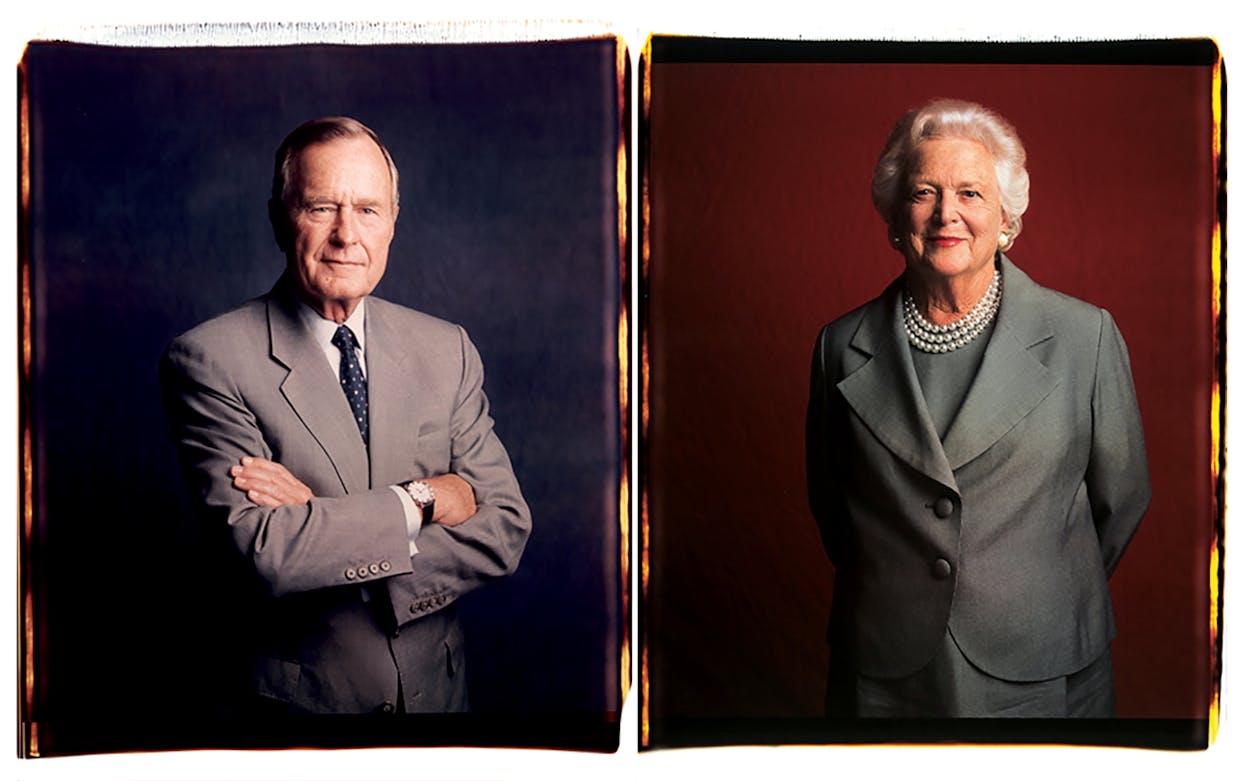

“History will confirm that George Herbert Walker Bush was a great president.” Maybe so, but the speaker of these words at the dedication of the George Bush School of Government and Public Service on the Texas A&M University campus was not exactly an unbiased source. Only a few moments before, he had begun his remarks by addressing the former chief executive and first lady as “Mr. President, [pause] Mother …” Acknowledging the ensuing laughter, the governor of Texas confided to the audience, “It works every time.”

But George W. Bush’s prediction of how history will treat his father may not work out as well. George Bush is one of five presidents in this century to be defeated for reelection (William Howard Taft, Herbert Hoover, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter were the others), and history so far has not been kind to the losers. The younger Bush went on to lay out a compelling enough case for the elder one—“He was a great president because, first and foremost, he was a great man. … He proved that you can enter the political arena and leave with your integrity. … He showed us that public service is worthy of our best efforts, the best years of our lives”—yet one has to look no further than the approval ratings of the current occupant of the White House to know that there is more to a successful presidency than character.

Almost five years have passed since George Bush was president, enough time and distance for the debate over his role in history to begin. And so it has: This summer economist Robert Reischauer, the former head of the Congressional Budget Office, credited the much-disparaged tax bill of 1990, agreed to by Bush despite his “Read my lips: no new taxes” pledge during the 1988 campaign, with helping produce the prolonged economic expansion of the Clinton years. Others have read Bush’s parachute jump last spring, at the age of 72, as an attempt to eradicate the “wimp” label that had dogged him in the latter part of his career. On November 6 the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum at A&M will be dedicated. Advance copies of the first biography of Bush that covers his presidential years, Herbert S. Parmet’s George Bush: Life of a Lone Star Yankee, are already out. The likelihood that George W. Bush will be a candidate for president in 2000 will no doubt lead to still more scrutiny, so that the sins and triumphs of the father can be visited upon the son. All history, it is said, is contemporary history, and that is certainly the case with the presidency of George Bush.

Such weighty matters, though, were far from the minds of the thousand or so spectators at the dedication of the Bush School. Most of them were Aggies—donors, alums, administrators, and faculty—who had turned out on a sweltering September afternoon to celebrate a great moment for Texas A&M as well as for George Bush. They sat underneath two white tents on a patch of ground that had been part of an experimental hog farm before then-president Bush chose A&M as the home for his presidential library in 1991—over Yale, no less, as well as a joint bid from Rice and the University of Houston. Now three new buildings occupied the site: the home of the Bush School, a conference center, and the almost-finished library. A detachment of the Aggie band greeted visitors with “The George Bush Presidential March,” composed especially for the occasion by the director of the marching band. The presidential party arrived under a canopy of crossed sabers formed by an elite unit of the Corps of Cadets. It was an Aggie ceremony all the way, even to the point that the audience punctuated the speeches not with applause but in traditional Aggie fashion, with approving bellows of “Whoop! Whoop!”

When the governor finished his introduction (“… the best dad a man could ever have …”), the forty-first president of the United States had the chance to make his own pitch to history. But he let it pass. The omission was deliberate: An hour or so earlier he had spoken briefly at a luncheon on campus, first praising Texas A&M, then explaining that he did not think it proper for him to go around playing up his presidency. “My mother used to say, ‘Don’t be a braggadocio,’” he had said. It was vintage George Bush, the kind of remark that causes the people who admire him to admire him all the more (for not bragging), and the people who scorn him to scorn him all the more (for bragging about not bragging and for sounding like a goody-goody).

This speech would prove to be no different. “We all learn about values,” Bush told the audience at the dedication. “We talk about values. It’s been said of me that I led a life of privilege, and I don’t think it’s meant to be flattering. Well, we could take care of ourselves when we were sick, but we were rich in values. We were taught to compete with honor, to be gracious in defeat—I’ve gotten very good at it, had lots of practice—to give back something to the community. Don’t brag, tell the truth, all those things.”

The message is worthy, but the messenger is too much a part of it. The focus shifts from Bush’s values to himself. Why deny his heritage? (One of his grandfathers was the first president of the National Manufacturers Association; the other, a Wall Street investment banker, lent his name to amateur golf’s Walker Cup.) Why denigrate himself? (At lunch, he had described a 1989 commencement address he had given at A&M as “a very important speech—probably not delivered very well—setting out the foreign policy of the United States.”)

Somewhere along the line, Bush’s greatest asset, his values, became his greatest weakness. In the eyes of the Left, his desire to “give back something” was born of noblesse oblige, not empathy. In the eyes of the Right, his commitment to public service was seen as proof that he didn’t believe in anything. His aversion to taking action just for the sake of short-term political gain was evidence not of responsible judgment but of timidity and his lack of “the vision thing.” Being “gracious in defeat” only verified that he was a wimp. Those who didn’t assail Bush’s values made sport of them. Bush, went the joke during the 1992 campaign, reminded women of their first husbands.

Image did not reflect reality, as Gail Sheehy pointed out in her 1988 book, Character: America’s Search for Leadership, in which she profiled six presidential candidates. Comparing Bush with Ronald Reagan, she wrote, “Bush has been married to the same woman for forty-two years; Reagan has been divorced. Bush says the proudest accomplishment of his life is that his kids still come home; only one of Reagan’s children bothered to show up at his seventy-fifth birthday party. Bush spends weekends in Kennebunkport urging his grandchildren to row across the pond and giving them the confidence to do it; Reagan never sees his grandchild and takes no one with him for weekends at Camp David except Nancy and the dog. George Bush was a genuine hero in World War II; Ronald Reagan was in Culver City making movies about it. The irony is that Bush really lives the eternal values so dear to conservatives’ hearts, while Reagan mouths them and winks.” Life is unfair, said Jimmy Carter. Maybe history will do better.

“I’m not trying to shape hisotry,” George Bush said. It was a few minutes after sunrise on the morning after the ceremony at Texas A&M, and Bush, as is his habit, was already in his West Houston office atop a suburban bank building. He was seated on a sofa with one arm slung over the back cushions. His crisp white shirt had an open collar, White House cuff links, and the smallest embroidered initials I have ever seen, an ever-so-discreet “GB,” in navy blue on the lone pocket. After a summer of golfing and fishing at the family retreat in Kennebunkport, Maine, he looked tanned and trim, his hairline and beltline holding steady. He does not particularly like to give interviews—the Beltway media, he says, is one thing he does not miss about Washington—and his mood on this morning when I asked him about his legacy was tolerant but not enthusiastic. “I’m not writing a memoir,” he added. “I’d rather let history decide.

“We did some good things,” Bush continued, but then he trailed off and had to be coaxed to give specifics. “Forming the coalition to fight Desert Storm. The Americans With Disabilities Act. The Clean Air Act was forward-looking.” He looked out the window, not wanting to make eye contact when talking about himself. Those who have been around Bush for many years would not be surprised by his reluctance to toot his own horn. In a memoir about writing speeches for Reagan and Bush, Peggy Noonan told of Bush’s aversion to the word “I” and how it forced her to construct pronounless sentences (“Moved to Texas, joined the Republican party, raised a family”), an awkward syntax that became fodder for Dana Carvey on Saturday Night Live. “The speculation among his friends and staff,” Noonan wrote, “was that it was due to his doughty old mom, who used to rap his knuckles for bragging, a brag apparently being defined as any sentence with the first-person singular as its subject.” Those close to Bush used to joke that if he became president, he would begin the oath of office with “Do solemnly swear.” One consequence of his reluctance to talk about himself was that the public never really got to know Bush beyond his résumé; as Noonan succinctly put it, he was famous but unknown.

Bush would talk no more about his legacy. “Had my chance,” he said. “We did our bit. We did a lot of things right, some wrong. I feel a little inhibited in trying to set the record straight. I have total confidence that objective scholars can do the job. The best example is Harry Truman. He left office lower than a snake’s belly. Then historians like David McCullough took an objective look at him, and now he’s respected because of his character.” (Barbara Bush, on the other hand, is not willing to be so passive about history. “Already the tide is turning,” she told me over the phone from Kennebunkport. “This is the Bush economy. [Newsweek columnist] Jane Bryant Quinn says it in every speech she makes. He gets credit for doing the hard thing. His tax policies saved Clinton, but they lost office for him.”)

Bush has settled into the role of ex-president. It is a good job once you get used to it. At first Bush took defeat hard; the Parmet biography says that on the weekend after the election, he told Colin Powell, “It hurts. It really hurts to be rejected.” Bush said that the return to private life wasn’t hard, but his description to me of his first hours out of office—“We flew to [Houston’s] Ellington Field and went straight to a small house where nobody was living”—sounded pretty bleak. In those early months, according to friends, he sometimes lapsed into apologies and regrets when he was around colleagues from the White House years. For Barbara Bush the transition was easier: “We’re not dumb enough to want what we don’t have,” she said. What they did have, courtesy of the federal government, was seven staffers and more than a dozen Secret Service agents, an annual pension of $148,000, and an annual budget of $391,000. And there are side benefits. If, say, you want to jump out of an airplane, the Pentagon will provide you with a paratrooper escort, at your cost.

The family routine is to spend summers in Kennebunkport until mid-October and the rest of the year at their Tanglewood-area home in Houston, except when they are traveling, which is often. Last year Bush spent 143 nights on the road. Immediately after our interview, he left for Arkansas and then headed overseas on a journey that would take him to Hong Kong, Spain (to see the Ryder Cup golf match), Monte Carlo, Switzerland, Germany, and Ireland. (Travel expenses are usually picked up by the groups he speaks to.) When he is in Houston, though, Bush is not a man-about-town. Always an early riser, he is up at five and in the office by seven. He answers mail and returns calls, works on speeches (some for charity, some for pay), puts the finishing touches on the foreign policy book he is writing with former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft (A World Transformed, scheduled for publication next September), and receives visitors. If he goes out for meals, he likes the Post Oak Grille, Ninfa’s, and the Bayou Club, which is so exclusive and so sensitive about its privacy that members who give debutante parties there are not permitted to mention the club in newspaper notices about the event. The clubhouse, near Interstate 10 and the West Loop, was one of local architect John Staub’s most famous creations and would be a Houston landmark if anyone could see it.

Nor do the Bushes stay out late. “We’ve never been night owls,” said Barbara Bush. “We’re always the first to leave a dinner party.” Most nights they watch TV. “We’re crazy about A&E and the History Channel,” she said, although, she added, “There’s too much Hitler.” They seldom go to movies; Bush has not seen Air Force One—“Should I see it?” he wanted to know—but he has heard about the airplane’s escape pod, which, of course, does not exist in real life. I decided not to ask about My Fellow Americans, whose plot has two bored ex-presidents putting aside their mutual dislike to join forces and foil a White House plot. In one scene the former first lady (Lauren Bacall) tells her penny-pinching husband (Jack Lemmon) to stop drinking vodka from the minibar in their hotel room and then refilling the bottles with water to avoid paying, because “It is so George Bush”—a farfetched cheap shot.

The Bushes do most of their entertaining in Kennebunkport, where days are divided between golf and fishing. This summer, in addition to their children, they hosted the Oak Ridge Boys, golfer Hale Irwin, mystery writers Mary Higgins Clark and Richard North Patterson, and Smith College president Ruth Simmons, who grew up in Houston’s Fifth Ward. Barbara Bush doesn’t go into town as much as she would like, because when she drives her blue convertible, strangers sometimes follow her. “I have to get there before ten, when the tourists start coming,” she said. “I can see people now, out my window, with binoculars trained on the house.” Restaurants are out too: “If I could give people one piece of advice, it would be, ‘Never go up to someone and say that you didn’t vote for her husband.’”

George Bush, meanwhile, has become a serious fisherman. The walls of his office are filled with photographs of some of the most famous and most powerful people in the world, but the ones he enjoys most are five shots of himself fishing on the rocks at Kennebunkport—a series in which he is dangerously engulfed by a sudden wave but keeps his balance. In August Bush went fishing for char in Canada’s Northwest Territories with Edmonton Oilers owner Peter Pocklington. The editor of the Deh Cho Drum—“Serving Eight Isolated Aboriginal Communities in Canada’s Subarctic”—heard about the trip and wrote Bush to ask him to write a column about his thoughts on fishing in the North. He got back a five-page fax. “I love fishing the Tree River,” Bush’s article began. “Way above the treeline, the fast-flowing Tree River pours its rushing green-grey waters into the Arctic Ocean, about a mile or two from where I fished for char. As the waters race over the boulders and rocks, you can catch an occasional glimpse of the majestic char, struggling to continue their fight against the current, their quests to reach their destiny.” He gave some advice about flies (“the Mickey Finn, the Blue Charm, and the Magog Smelt all worked well”), confessed that he had 43 fish on his fly rod but landed only 2, and passed along a piece of advice. “I learned that the way to get lots of fish on the line is to keep the hook in the water. Obvious? Well, maybe, but a lot of fishermen seem to hang out waiting for someone else to catch one before they do serious fly casting.”

It is a not a bad metaphor for the career of someone who lost a couple of Senate races but kept his hook in the water—congressman, United Nations ambassador, GOP chairman, envoy to China, CIA director, on the short list for vice president for Gerald Ford—until eventually the big one came along.

One place that George Bush does not like to visit is Washington. It is a city for ins, and he is out. What he misses most, he says, is the familial relationship that he developed with the White House support staff: the cooks, the telephone operators, the Marine pilots, the horseshoe tournaments when they all got together. He did agree to return last September as the main speaker for the fiftieth anniversary of the CIA, an organization for which he has high regard—and he laments that others do not. “It bothers me that people buy into any kind of conspiracy theory,” he said during our interview. “My own grandkids do it. ‘Is it true you were head of the CIA, Gampy? What did you do with those people from outer space?’”

Like most ex-presidents—Nixon and Carter have been the exceptions—Bush rarely speaks out on the issues of the day. “No Larry King, no op-ed pieces,” he told me. He has rarely broken his silence and then mainly on the subject of China (“I’m very worried about it”) in speeches in which he argues that a U.S. policy of free trade and open contacts, rather than threats and isolationism, will lead to more freedom in China. Every political reporter in America would love to know what Bush really thinks of Bill Clinton and his fundraising scandals, but the only one to have any success was a USA Today reporter who came to talk about Bush’s interest in volunteerism and slipped in a mention that Clinton’s defenders were saying every administration used the White House to raise money. Bush made it clear that he didn’t do it. Barbara Bush, however, is not so reticent about the subject of Clinton (or anything else). She was appalled by news reports that (1) he takes mulligans, or second-chance shots, when playing golf and (2) that it’s okay to do so because everybody cheats at golf. “Everybody does not cheat at golf,” she said. “We played nineteen holes today. It took that long to get a winner, and nobody cheated. Nobody we play golf with would play with us if we cheated.”

Another subject that is taboo with Bush but not with his wife is George W.’s political future. The former president claims to give his son no political advice, but he allows that “his mother may.” Though the official line from the state capitol is that the governor is looking no farther ahead than his 1998 race for reelection, she certainly seems to be. “It’s all timing,” she said. “He’s the greatest guy in the world, but timing is everything in politics.” She watched her son speak at a GOP rally in Indianapolis, a performance that was panned both for substance (“The media wanted red meat for national politics in 2000,” the governor had told me, “and I gave them Texas in 1997”) and for delivery. “I was shocked by the press reaction,” Barbara Bush said. “I thought it was a great speech. I watched it while I was having my nails done, and my manicurist cried.”

She is also more willing than her husband to talk about how historians should regard George Bush. “He taught us—whether we learned the lesson or not—how to keep the peace,” she said. “He believed in quiet diplomacy, talking things out first. People don’t realize how difficult it was for some of those Arab countries to join the Desert Storm coalition. There has never been anyone who could negotiate as well as he did. We haven’t done it since. We have even publicly humiliated our friends.”

Even if George Bush were inclined to speak out, the thought of dealing with the media again would likely be enough to dissuade him. It’s not that he has a Nixonian bitterness toward the press; rather, he is all too aware that he wasn’t good at conveying his ideas. “I accept responsibility,” he said. “I wasn’t articulate enough in setting out my vision of a shining city [the phrase is from Reagan’s farewell address] on the hill. I always took out speechwriters’ rhetoric.” Barbara Bush, on the other hand, is not so forgiving: “When Diana was killed,” she said, “I watched the three talking heads from the networks knock the paparazzi, and I thought, ‘They’re just dressed-up paparazzi.’” One of the reasons she gives for Bush’s defeat in 1992 is that “the press led everybody to believe that the economy was bad when it really wasn’t.” (The other two: the generational difference between Bush and Clinton and the end of the communist threat to the United States, which negated Bush’s political strength as a world leader.)

Two encounters with the media troubled the Bushes in particular. One was the report of son Neil’s involvement in the failure of Silverado Savings, Banking, and Loan Association in Denver, where he was an outside director. Neil Bush did receive a generous line of credit for an oil and gas venture, but he was a minnow among sharks compared to what was going on throughout the S&L business. The episode would not have been newsworthy except that Neil had a prominent father. “It broke George’s heart,” Barbara Bush said. The other was Newsweek’s “Fighting the Wimp Factor” cover story on Bush in October 1987, a little more than a year before the presidential election. When I asked him about it, Bush showed real emotion for one of only two times in our interview. “With apologies for bragging,” he said, “I don’t think I have to defend myself that I am not a wimp. I am not going to be like Nixon: ‘I am not a crook.’”

“Did these attacks on your character take a toll on you as president? I asked.” “There was no toll,” Bush said. “It enriched my life immensely. I vowed that I would never complain—none of this, ‘Nobody knows the burdens I faced.’”

“One more question,” I said. “Is there anything about the job that might cause you to say to someone close to you—not to mention any names, of course—that being president isn’t worth it?”

This was the second time that Bush showed emotion. “Oh, hell no,” he said.

American presidents are among the most analyzed, most written about people in the world, and yet the essence of them often eludes their contemporaries. George and Barbara Bush each told me, in response to a question, that they thought the American people never quite knew who he was. “Sometimes, yes, sometimes, no, but overall, no,” Bush said. “‘Hey, you got a sense of humor,’ people say to me. ‘I never would have thought that.’” Perhaps the Bush library will remedy that, just as research done at other presidential libraries has shed new light on Truman, Eisenhower, and Johnson. Bush perks up when he starts talking about the library’s up-to-date technology. “I believe that modern communications, connective computers, which I don’t really understand, will make the record easy to evaluate,” he said.

But other things will make it difficult. Presidential papers have become a political football in recent years, the object of a controversy over the right to know and the right to privacy, and history is the loser. The issue of whether the president or the public owns the papers—not just the official documents, but the letters, memos, notes, and briefings that are invaluable to historians—goes back as far as George Washington, who took all of his papers with him when he left office. After Franklin Roosevelt established the first presidential library, the practice was for a president to deed his personal papers to the National Archives and retain the right to determine which ones would be withheld from public view and for how long. This worked fine until Richard Nixon claimed ownership of his personal papers when he resigned from office. Congress took exception, and the Justice Department seized the records. To prevent such a recurrence, Congress in 1978 passed the Presidential Records Act, which defined which such records were public.

But the law has had unforeseen consequences that will limit research at the Bush library: More records are closed today than would have been closed under the old system. Under the Presidential Records Act, the archivist becomes a policeman who must withdraw papers if they fall into one of twelve categories. The most controversial one is “confidential advice.” Just about everything that is of interest to researchers is, in some way, confidential advice. I looked through a couple of boxes of papers in the Bush library, and they were laden with pink sheets describing documents that had been withdrawn. Most of the missing papers appeared to be totally innocuous; for example, one involved the award of a technology medal, which apparently depended upon confidential advice. After many years have passed (there is no set time limit), all of the withdrawn documents will eventually be returned to the files; in the meantime, researchers can use a cumbersome procedure to appeal the withdrawal of papers. Archivists at the Bush library fear that soon they will be buried by a backlog of such requests.

A lot of people were surprised when Bush picked A&M as the location for his library—his only prior connection with the school or with College Station was an honorary doctorate he received in May 1989—but as the building neared completion this fall, the logic of his choice was clear. Though the federal government provides the staff for the library through the National Archives, the building itself must be paid for with private funds, and Aggies love to part with their money when their school comes calling. When David Alsobrook, the archivist who is the executive director of the library, was asked what he wanted the building to have, he answered, “Everything every other presidential library wished they had.” A&M saw that he got it.

The library has an extensive museum, a separate gallery for temporary and traveling exhibits, and a classroom for schoolchildren who visit, in addition to stack space for more than 38 million pages of documents. Visitors to the museum are greeted by an airplane hanging from the ceiling; it is of the same type as the one Bush had to ditch in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. (Amazingly, someone from the ship that picked him up filmed the rescue on a home movie camera, kept the reel, and many years later, realized who was on the film. Now the scene is preserved on videotape at the library.)

Most of the papers are kept in a climate-controlled room the size of half a football field. “This may remind you of Raiders of the Lost Ark,” Alsobrook said as he punched a code that opened the door. He was referring, of course, to the movie’s closing scene of the storage place for the Ark of the Covenant, a warehouse filled with endless rows of crates and boxes. In the Bush library the crates were stacked haphazardly along the walls of the room and had “NO GUITAR” scrawled on them, indicating which crates had been searched, fruitlessly, in an effort to locate an instrument that had been a gift to the president from B. B. King. The papers resided in brown and gray boxes on shelves that extended in some cases to fifty yards in length, brown indicating that the papers therein had not been processed, gray that they had been—and there was a lot more brown than gray.

This means that the historical judgment on the legacy of George Bush may be a longer time in coming than he would hope. In the meantime, let’s try to anticipate what questions the historians will ask and see whether any answers are available now.

Were his policies sound? From the short-term perspective of 1997, Bush is looking very good. Whether he decided consciously not to try to stimulate the economy, or decided by not deciding, the result of his inaction was that good times came back without federal intervention, though too late to help him win reelection. Indeed, it is hard to find an area where Bush made an obvious policy mistake. Candidate Bill Clinton assailed Bush’s pro-China trade policy for “coddling dictators”; President Clinton follows Bush’s lead. The tax bill of 1990 now is seen as the first step toward deficit reduction. The international coalition Bush assembled against Iraq, which included the Soviet Union and key Arab countries, provided a moral basis for American military action that hasn’t existed, at home or abroad, since World War II. (“Desert Storm was one of the great achievements of the twentieth century,” George W. Bush told me, “and it had a shelf life of about a month.”) His caution during the disintegration of the Eastern bloc and of the Soviet Union—by not going to Berlin to, as he put it, “dance on the wall”—gave communist hard-liners no excuse to mount a counterrevolution. Sometimes what doesn’t happen is as important as what does happen.

Why didn’t he get full credit for his policies? Because he wasn’t Ronald Reagan. Reagan cut taxes but he also signed major tax bills; he helped drive the Soviet Union to economic ruin but in the process he rolled up budget deficits of unimaginable size; he became mired in the Iran-Contra scandal; and whatever he did, the public loved him. It was Bush’s bad timing that his shortcomings—a lack of ideological vision, the inability to articulate his ideas, the difficulty of getting across to the public who he really was—were the flip side of Reagan’s strengths. Conservatives accused him of squandering the Reagan legacy, but Reagan himself would have had a hard time staying on course with the deficit out of control and a highly partisan Democratic Congress aligned against him.

Was Bush’s lackluster 1992 campaign the result of a physical and mental letdown? The idea comes from biographer Parmet, who had access to transcripts of Bush’s diaries. “I don’t know whether it’s the anticlimax or that I’m too tired to enjoy anything, but I just seem to be losing my perspective,” Bush wrote in March 1991. Another excerpt from that month: “Sometimes I really like the spotlight, but I’m tired of it. I’ve been at the head table for many years, and now I wonder what else is out there.” A few days later: “For some reason, my whole body is dragging and I’m tired. I don’t understand it.” In April, Parmet reports, a staffer told the White House physician that there were changes in Bush’s handwriting. His sleep pattern was more erratic than usual, and he was losing weight. Press secretary Marlin Fitzwater told Parmet, “There was a point after the war, it seemed to me, that he had a real feeling he didn’t want to run.” On May 4 Bush developed a shortness of breath while jogging at Camp David and was airlifted to Bethesda Naval Hospital. Even after he recovered, aides kept telling his doctors that “the president didn’t seem to have the same zest as he used to.” Barbara Bush told me that her husband never seriously considered not running for reelection, but it seems evident that at the very least, he lacked fire, especially about resuming domestic hostilities with Senate majority leader George Mitchell. In our interview Bush described the Maine Democrat to me as “the most partisan leader I’ve ever come up against. He was determined to frustrate everything we tried to do.” And yet, ever the gentleman and probably too much so, Bush would offer Mitchell a ride on Air Force One when he went to Kennebunkport.

Why didn’t Bush’s values count for more? This, finally, is the overriding question of the Bush presidency. One answer is that Bush’s emphasis on integrity could be a handicap at times. When he acted like a typical politician—by captializing on the furlough granted to convicted killer Willie Horton in 1988, for example—he was particularly vulnerable to the charge that he was compromising his high standards to get the presidency. Another answer is that his frequent references to his code of values reminded the public of his establishment background: It is easy, or at least easier, for the privileged to play by the rules. Bush’s values were virtues that he urged for individuals, unlike Ronald Reagan’s values, which were virtues that he urged for the nation. Reagan’s values were more relevant to politics than Bush’s were. So, in the 1992 election, were Bill Clinton’s: Politics is about public values. George Bush lost to a lesser man but a greater politician. Sometimes integrity and the best of intentions are not enough to prevent disappointment and defeat.